Media Education in 12 European Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue No. 45 Spring 2019

ISSUE NO. 45 SPRING 2019 AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION FOR THE NORTHHOLM GRAMMAR SCHOOL COMMUNITY LEARN WITH PURPOSE LIVE WITH PASSION 1 2 THE ARCADIAN ISSUE NO.45 Contents 5 CHAIR OF 14 FROM THE 33 CAREERS COUNCIL DIRECTOR EVENING John Hayes OF STUDENT DEVELOPMENT 34 VISUAL ARTS 6 FROM THE Jenny Plüss PRINCIPAL 36 STEM Christopher Bradbury 37 SCIENCE 8 COMMISSIONING OF THE PRINCIPAL 18 LEADERSHIP 2019 20 CLASS OF 2018 22 SPORT 38 PDHPE 39 ANZAC DAY 10 JUNIOR 40 DUKE OF SCHOOL EDINBURGH Verity Paterson AWARD 42 NORTHHOLM ASSOCIATION 26 DRAMA (P&C) 28 CAMPS 44 NOSU 12 FROM THE DIRECTOR 47 ARCHIVES OF LEARNING AND TEACHING Catherine Manalili 3 4 THE ARCADIAN ISSUE NO.45 Chair of Council Northholm has a great deal to recommend it What a delight it is to have the opportunity to interact with If I pick March as one month of co-curricular activity, students, staff and parents (individuals and the Northholm I see among many other activities, success in the Hills Zone Association) and to read current school documents in this Swimming Carnival with the winning of “The Percentage exciting year in the life of Northholm. Shield” and 12 and 13 Year Age championships, music students performing to residents of Rowland Village as a contribution At the end of 2018 the School Council appointed Mr Chris to community, additional tuition in ceramics and Women in Bradbury from The King’s School as Principal of Northholm, Film, work on the School Production, The Taming of the Shrew, and we are very pleased with his enthusiasm, his leadership and a musical theatre performance club, Theatresports, some of our his hard work during 2019. -

How Schools Are Integrating New Migrant Pupils and Their Families

HOW SCHOOLS ARE INTEGRATING NEW MIGRANT PUPILS AND THEIR FAMILIES Chiara Manzoni and Heather Rolfe March 2019 About the National Institute of Economic and Social Research The National Institute of Economic and Social Research is Britain's longest established independent research institute, founded in 1938. The vision of our founders was to carry out research to improve understanding of the economic and social forces that affect people’s lives, and the ways in which policy can bring about change. Eighty years later, this remains central to NIESR’s ethos. We continue to apply our expertise in both quantitative and qualitative methods and our understanding of economic and social issues to current debates and to influence policy. The Institute is independent of all party political interests. National Institute of Economic and Social Research 2 Dean Trench St London SW1P 3HE T: +44 (0)20 7222 7665 E: [email protected] niesr.ac.uk Registered charity no. 306083 This report was first published in March 2019 © National Institute of Economic and Social Research 2019 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ ii 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives .................................................................................................................................... -

Key Stage 4 Options Booklet

Key Stage 4 2020 Options Booklet St. Mary’s Catholic High School Chesterfield Gaudium et Spes “Live, Love and Learn in the Light of Christ” CONTENTS Pages THE GCSE SUBJECTS AT KEY STAGE 4 3 YEAR TEN AND YEAR ELEVEN KEY STAGE 4 COURSES 4 - 18 - CORE SUBJECTS 4 - 8 - OPTIONAL SUBJECTS 9 - 18 MAKING YOUR CHOICE 19 ENROLMENT REQUIREMENTS FOR SIXTH FORM 20 2 THE GCSE SUBJECTS AT KEY STAGE 4 CORE SUBJECTS: Religious Education Mathematics English Language/English Literature Triple Science (which counts as three GCSE’s) or Combined Science (which counts as two GCSEs) PE History or Geography All pupils will study all of the core subjects above and will chose from the option subjects below. It is important to maintain a breadth of curriculum to enable successful progression later on. The Government wants the majority of students to follow a curriculum, which contains the subjects of the English Baccalaureate (English, maths, science, history or geography and a modern or ancient language). The Ebacc is a suite of subjects not a qualification in itself. Employers may well look for these qualifications as well as other skills and attributes. We believe that our curriculum offers choice for all students of all abilities and we will continue to personalise and direct pupils’ choices based on previous attainment, potential and the professional advice of staff. All pupils must choose either history or geography and two other subjects. Pupils who are capable of studying a language to GCSE (Spanish, French or German) will be guided to choose a language in addition to either history or geography. -

Year 9 Options 2021

Year 9 Options 2021 Introduction The purpose of this booklet is to provide you and your parents with information which will help towards making decisions about which subjects you should study in Years 10 and 11. The end of Year 9 represents a landmark in your school life as it represents the point at which you embark on examination courses that will have a large influence on the rest of your life. Many of the subjects will be building on the skills and knowledge acquired during Years 7, 8 and 9, but there will be an opportunity to take up new subjects or specialise in areas where you have shown ability and interest. This booklet is part of the information gathering process which will help you to make your decision about which options to take. Good choices will help to make the next two years both happy and worthwhile. It is also important that you realise what you are taking on when starting on courses that lead to GCSE exams. You should think carefully before making your choices. You will be given as much help as possible. There will be revision classes and mock exams as well as many opportunities to talk to teachers about your progress. Most importantly, it will be down to you. Your success will be determined by your attendance, organisation and effort with both class and homework. 2 Key Stage 4 Rationale English Baccalaureate The English Baccalaureate (EBacc) is a performance measure for schools, awarded when students secure a grade 4 or above at GCSE level across a core of five academic subjects: English, mathematics, history or geography, the sciences and a language. -

KS4 Pathways Booklet 2018-2020

GCSE CURRICULUM KS4 PATHWAYS 2018 - 2020 We are inspired by our Patron, Bishop Richard Challoner, and his call for us to “do ordinary things extraordinarily well” 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Head & Deputy’s Foreword ................................................................................... 3 Choosing a KS4 Curriculum Pathway ..................................................................... 5 Final Pathway Form .............................................................................................. 6 SECTION 1: Core Subjects ................................................................................ 7 Religious Studies ................................................................................................... 8 English ................................................................................................................... 9 Mathematics ....................................................................................................... 13 Science ................................................................................................................ 14 SECTION 2: EBACC Element ........................................................................... 16 Modern Languages (French & Spanish GCSE) ..................................................... 17 Geography .......................................................................................................... 20 History ................................................................................................................ 21 SECTION -

KS4 Choices Booklet 2016-2019 Springwood High School

Springwood High School Phone: 01553 773393 Fax: 01553 771405 Email: [email protected] www.springwoodhighschool.co.uk KS4 Choices Booklet 2016-2019 Springwood High School A guide for pupils and parents in making the choice of subjects and courses from those available for 2016—2019 (Year 9 to Year 11) Contents PAGE NUMBER Key Stage 4 at Springwood High School 2 Subjects taken in Years Nine, Ten and Eleven 3 Where to go for advice 5 Opportunities for parents to seek advice 5 Level of course 6 Instructions on how to fill in your choice sheet 6 SECTION A - Core Subjects English 7 Mathematics 8 Science 9 Religious Studies 10 Physical Education (core) 11 SECTION B - Selected Subjects Art and Design 12 ASDAN 13 Business 14 Computer science 15 Construction 17 Dance 18 Design & Technology 20 Drama 21 Economics 22 Food Preparation and Nutrition 23 French 30 Geography 25 German 30 Hair and Beauty Services 27 Health and Social Care/Child Development 28 History 29 Music 31 Performing Arts – Musical Theatre 33 Photography 34 Physical Education 35 Sociology 36 Spanish 30 SECTION C – Completing the form Quick guide to what’s happening when 37 Notes for completing the subject choices form 39 Subject choices form 40 1 Key Stage 4 at Springwood High School At Springwood we are committed to all students achieving the best they can while at the school. At Key Stage 4 this means students leaving at least 9 GCSEs or equivalent qualifications at the best grade possible for the student. We offer an extremely wide range of subjects for study in Years 9, 10 and 11, and so it is important that the right decisions are made to allow appropriate pathways into further education and employment. -

Drug and Alcohol Education in Schools

Drug and alcohol education in schools By Nick Boddington BA (Hons) MEd MSc, Jenny McWhirter PhD and Aidan Stonehouse PhD September 2013 Executive summary This research is based on a detailed online survey of respondents from 288 schools, and 20 follow-up phone interviews conducted with respondents from a range of primary and secondary settings. It was commissioned to inform the development of the Alcohol and Drug Education and Prevention Information Service (ADEPIS) and its support for schools. Key findings Drug and alcohol education provision remains inconsistent in delivery across educational establishments within England. Primary school settings remain less confident in their ability to access effective resources and to provide best practice in drug and alcohol education provision. A fifth of respondents from primary schools (19%) felt they had little access to effective resources for teaching drug and alcohol education. Four-fifths (81%) of all respondents said they would like more classroom resources for drug and alcohol education. While elements of good practice exist throughout educational settings, assessment and evaluation, continuity in learning and quality assurance of resources and external support remain weaker areas. While there are numerous examples of excellent PSHE/drug and alcohol education teaching, overall many practitioners continue to feel constrained by a lack of curriculum time to build continuous learning, and gaps in finance for resources and staff training. Staying up-to-date on information and resources around drugs represents a particular concern for teachers, especially in secondary settings. Interview discussions reveal that practitioners continue to require advice on how to interact with parents around drug and alcohol education, particularly in primary settings. -

Program of Studies 2019-2020

Moorestown High School 350 Bridgeboro Road, Moorestown, NJ 08057 PROGRAM OF STUDIES 2019-2020 “HIGH EXPECTATIONS - HIGH SUPPORT - HIGH ACHIEVEMENT” 2019-2020 Program of Studies Moorestown High School Telephone: (856) 778-6610 Facsimile: (856) 722-8983 Website: www.mtps.com Administration Mr. Andrew Seibel Principal Mr. Don Williams Assistant Principal Mr. Robert McGough Assistant Principal Dr. David Tate Pupil Services Director Ms. Kathleen D’Ambra Guidance Services Administrator Mr. Shawn Counard Supervisor of Athletics Supervisors Ms. Jacqueline Brownell Mrs. Julie Colby Language Arts Literacy Mathematics Mr. Gavin Quinn Ms. Roseth Rodriguez Science Social Studies/World Languages Mr. Shawn Counard Mrs. Patricia Rowe Health/Physical Education Arts and Technology Mrs. Cynthia Moskalow Special Education NOTE: It is our continuing goal to offer a comprehensive Program of Studies. Final decisions regarding the actual offering of proposed or existing courses for the 2019-2020 school year will be dependent upon budget approval and/or the number of requests for those courses. Courses with fewer than ten (10) students assigned need Board approval to be scheduled. Therefore, not all courses listed in this catalog are guaranteed to run during the 2019-2020 school year. Introduction 2019-2020 1 2019-2020 Staff by Department Athletics/Student Activities Mathematics Science Shawn Counard, Supervisor Julie Colby, Supervisor Gavin Quinn, Supervisor Justin Miloszewski, Trainer Brian Cary Kathie Alpert Eileen Fitzpatrick Jinnie Anstice Physical Education/Health Julie Fleming Jason Banyai Shawn Counard, Supervisor Beth Glennon Dana Church-Williams John Battersby Kristin Hanratty George Engle Megan Collins Gina Higgins Donna Harvey William Donoghue Timothy Hurley Allen Kolchinsky Russell Horton Kylie Johnson Raymond Kucklinca Deanna Knobloch Rachel Long Lea Marano William Mulvihill Angela Murphy Daniel Miller Beau Sherry Brian Orak Tracee Panetti Barbara Young Christa Potts Tyler Sheilds Christine Regn Pamela Shepard Child Study Team Paul Sinatra Erin Todd Dr. -

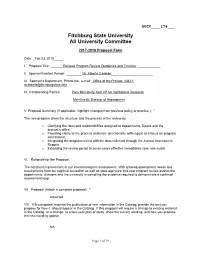

Program Review Cycle and Procedures

AUC#____176___ Fitchburg State University All University Committee 2017-2018 Proposal Form Date: _Feb 23, 2018_____ I. Proposal Title: _______Revised Program Review Guidelines and Timeline _____________ II. Sponsor/Contact Person: _________Dr. Alberto Cardelle_______________________ III. Sponsor’s Department, Phone No., e-mail:_Office of the Provost, x3421, [email protected] IV. Collaborating Parties: ______Pam McCaferty Asst VP for Institutional Research_______________ _______Merri Incitti, Director of Assessment_________________________ V. Proposal Summary (If applicable, highlight changes from previous policy or practice.): * The new program alters the structure and the process of the review by o Clarifying the roles and responsibilities assigned to departments, Deans and the provost’s office. o Providing clarity to the process and more directionality with regard to a focus on program assessment. o Integrating the program review with the data collected through the Annual Assessment Reports o Extending the review period to seven years effective immediately (see new cycle) VI. Rationale for the Proposal: The continual improvement of our internal program assessment. With growing assessment needs and requirements from our regional accreditor as well as state agencies, this new program review assists the departments, divisions and the university in compiling the evidence required to demonstrate a continual assessment loop. VII. Proposal (Attach a complete proposal): * Attached VIII. If this proposal requires the publication of new information in the Catalog, provide the text you propose for how it should appear in the Catalog. If this proposal will require a change to existing material in the Catalog, or a change to a four-year plan of study, show the current wording, and how you propose the new wording appear. -

U.S. General Notes and Annex 1 to U.S. General Notes

GENERAL NOTES TARIFF SCHEDULE OF THE UNITED STATES 1. Relation to the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS). The provisions of this Schedule are generally expressed in terms of the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States, and the interpretation of the provisions of this Schedule, including the product coverage of subheadings of this Schedule, shall be governed by the General Notes, Section Notes, and Chapter Notes of the HTSUS. To the extent that provisions of this Schedule are identical to the corresponding provisions of the HTSUS, the provisions of this Schedule shall have the same meaning as the corresponding provisions of the HTSUS. 2. Base Rates of Duty. The base rates of duty set forth in this Schedule reflect the HTSUS Column 1 General rates of duty in effect January 10, 2003. 3. Staging. In addition to the staging categories listed in Annex IV, paragraph 1, this Schedule contains staging categories U, V, and W: (a) duties on goods provided for in the items in staging category U shall be eliminated entirely and such goods shall be duty-free on January 1 of year one. For goods in tariff items 9812.00.20, 9812.00.40, 9813.00.05, 9813.00.10, 9813.00.15, 9813.00.20, 9813.00.25, 9813.00.30, 9813.00.35, 9813.00.40, 9813.00.45, 9813.00.50, 9813.00.55, 9813.00.60, 9813.00.70, 9813.00.75, and 9814.00.50, duty-free means free without bond; (b) goods provided for in the items in staging category V shall be duty-free immediately in accordance with existing WTO duty-elimination commitments (WTO Schedule XX for the United States); and (c) goods provided for in the items in staging category W shall be subject to the following provisions until January 1 of year nine, at which time such goods shall be duty-free: (i) for goods described in tariff item 9802.00.80, at the time of importation the duty imposed upon the assembled article to be applied in accordance with the procedures specified in U.S. -

A Guide for Students and Parents 2011-12

A Guide for Students and Parents 2011-12 Among the best schools in the Country. The Thomas Hardye School An exceptional school. OFSTED Contents Welcome to The Thomas Hardye School 1 OFSTED report 2 Every Child Matters Student Voice and Year Councils; Extended Schools; Students and Tutors; Year Teams; The School day; Student Diary; Student and Family Support Group 3-5 Uniform 6 Personal Responsibility Rewards; Leaving the Premises; Leave of Absence; Valuables; Mobile ’phones; Food and Drink; Smoking; Sanctions 7 Parents and School in Partnership Home-School and Sixth Form Agreements; Religious Education; Information Evenings; ‘Newslines’; School Calendar; Thomas Hardye Direct; The VLE 8-9 Specialisms High Performing Specialist School; Science, Humanities and Special Needs 10 Developments Training School; SCITT; Leading Edge School; DASP; Advanced Skills Teachers 11 Year Nine Curriculum 12 Year Ten and Year Eleven Curriculum 13 The Sixth Form 14-15 Resources Resources Centre & Sports Hall; Information & Communication Technology Centre; other facilities 16 Careers Education Careers Education Modules; Appointments; Resources; Work Placements 17 Student Assessment Consultation Evenings; Reporting to Parents; Thomas Hardye Direct; Homework; Marking Policy; 18 Learning for All The Web Site; Films for Learning; In the Curriculum; Thomas Hardye Television 19 Physical Education 20 Outdoor Education Sailing, Kayak, Climbing, Water Polo Clubs; Duke of Edinburgh’s Award 21 Performing Arts Music; Dance; Drama 22, 23 Beyond the Classroom Exchanges and Field Trips 24 Industry Partnerships Science College Links 25 Community and Business Partnerships Community and Work Placement Links 26 League Tables 27 Year 13 IB student ‘Bird in Flight’ Year Admissions 28 www.thomas-hardye.dorset.sch.uk The Thomas Hardye School aims to ❁ ensure that all students receive the best ❁ provide a stimulating environment which education we can provide, regardless of shows students that learning is exciting and a social, financial, religious or racial background valuable life-long activity. -

Our Thomas Estley Community College Newsletter October 2020

Welcome to our Thomas Estley Community College Newsletter October 2020 Dear parents and carers, I write to you at the end of a half term of hard work, commitment to learning and determination to overcome barriers. I am very proud of both students and staff—embodying all that it means to be a ‘Community of Courage and Commitment to Success’ in the most challenging times. We have carefully followed national Covid guidance for schools and have been delighted to achieve half a term without any positive Covid cases in the college community. This has enabled us to protect learning and to begin to catch up progress gaps. Unfortunately, it has also curtailed many of our extracurricular opportunities, limited the styles of pedagogy available to teachers, limited our catering offer and movement around site, enforced virtual parents evenings, Y11 Awards evening and our usual Open College week, and seen us having to adjust many processes and policies. We have not felt much like a Community College this half term, which has been hard to bear and very different to our usual offer and provision. Our half term has been bracketed by a pre-opening visit by the Education Minister Nick Gibb, who praised our ‘Covid-secure’ site, and a visit yesterday by Ofsted HMI inspectors, who listened carefully to our safeguarding, curriculum, online learning, attendance and behaviour adjustments around the challenge of Covid, to check out our approach and to take away some good practice for a national Ofsted report. Although I am proud to receive this positive feedback, I am most proud of the fantastic attitude of our learners and our staff.