Why Teach Handwriting? an Anecdotal Book Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19Th Century Writing Activity: Pen &

Lesson Plan: #NoyesArtatHome 19th Century Writing Activity: Pen & Ink Activity based on letters on display in the Noyes Museum’s Estell Empire Exhibition For ages 12 & up Experience with cursive* writing not necessary Assistance from an adult would be helpful. Overview: Round Hand Script: This was the dominant cursive* writing style among 19th century writing “masters,” whose An account book from John Estell’s general store models were engraved on metal. Letters Circa 1836 – 1837 sloped to the right, and thick lines were © Collection of Stockton University produced on the downstrokes using a flexible, straight-edged (not pointed) pen nib (tip). Thin lines were made by using the corner of the nib. Round hand included decorative swirls referred to as “command of hand.” Copperplate: This type of writing was made with a flexible, pointed metal pen. Copperplate script differs from round hand in the gradual swelling of the broad strokes on curved forms and the narrowness of the backstrokes of b, e, and o. Definitions from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-letter Project Description: This lesson provides a brief overview of handwriting in the 19th century and a hands-on writing activity. First, paint with a teabag to make “old” looking paper. To write, use a quill** pen with black ink or watered-down paint, or a marker. Try to read and copy the example of 19th century writing. Can you write your own name, or a whole letter to a friend? Supplies: 8.5 x 11” piece of paper A tea bag; preferably a darker tea such as black tea (Lipton, Red Rose) A watercolor brush Your choice of: a quill** pen and black ink, watered-down black paint with a fine-tipped brush, or a black marker (for example: Crayola – “broad line” or Sharpie – “fine point,” the newer, the better) *Cursive writing is a style of writing in which all of the letters in a word are connected. -

Vaikuntha Children.) Methods from Each of These Large Categories Can Be Combined to Create Many Specific Ways to Teach

Please Read This First This book is for teachers, parents, ISKCON leaders, students, and anyone interested in conscious education. Here we are neither presenting a blueprint for a traditional gurukula nor what you probably feel a curriculum should be after reading Çréla Prabhupäda’s instructions. It is an adaptation for our present needs in Western countries. Certainly, what we suggest is not the only way but if you’re starting and don’t know what to do, we hope to be of help. For veteran educators, there are many ideas and resources which can enhance your service. Because we are now using mostly non- devotee teaching materials, the amount of Kåñëa consciousness being taught depends upon the individual teachers. Kåñëa consciousness is not intrinsic in these curriculum guidelines but we have tried to select the most efficient and least harmful methods and materials which should make the injection of spiritual principles easiest. By following the guidelines suggested here, you can be reasonably assured that you will meet all legal requirements, have a complete curriculum, and that the students will get a good education. Although this book follows a logical order from beginning to end, you can skip through and pick what is of most value to you. Additionally, a lot of important material can be found in the appendixes. New educational material is constantly being produced. Suppliers come and go. Therefore, some of this information is dated. Please update your copy of this guidebook regularly. We have included some quotes from Çréla Prabhupäda, called “drops of nectar,” at the beginning of most chapters. -

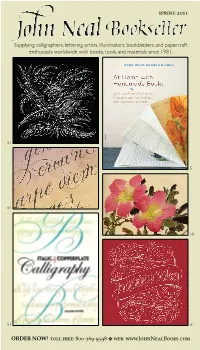

Spring 2011 Supplying Calligraphers, Lettering Artists, Illuminators

spring 2011 Supplying calligraphers, lettering artists, illuminators, bookbinders and papercraft enthusiasts worldwide with books, tools, and materials since 1981. 61 5 64 50 61 61 ORDER NOW! toll free: 800-369-9598 v web: www.JohnNealBooks.com Julie Eastman. B&L 8.2 “...an informative, engaging, Bill Waddington. B&L 8.2 and valued resource.” Need something new to inspire you? –Ed Hutchins Subscribe to Bound & Lettered and have each issue – filled with practical information on artists’ books, bookbinding, calligraphy and papercraft – delivered to your mailbox. Bound & Lettered features: how-to articles with helpful step-by-step instructions and illustrations, artist galleries featuring the works of accomplished calligraphers & book artists, useful articles on tools & materials, and book & exhibit reviews. You will find each issue filled with wonderful ideas and projects. Subscribe today! Annie Cicale. B&L 8.3 Every issue of Bound & Lettered has articles full of practical information for calligraphers, bookbinders and book artists. Fran Watson. B&L 8.3 Founded by Shereen LaPlantz, Bound & Lettered is a quarterly magazine of calligraphy, bookbinding and papercraft. Published by John Neal, Bookseller. Now with 18 color pages! Subscription prices: USA Canada Others Four issues (1 year) $26 $34 USD $40 USD Eight issues (2 years) $47 $63 USD $75 USD 12 issues (3 years) $63 $87 USD $105 USD mail to: Bound & Lettered, 1833 Spring Garden St., First Floor, Sue Bleiwess. B&L 8.2 Greensboro, NC 27403 b SUBSCRIBE ONLINE AT WWW .JOHNNEALBOOKS .COM B3310. Alphabeasties and Other Amazing Types by Sharon Werner and Sarah Forss. 2009. 56pp. 9"x11.5". -

George Bickhams Penmanship Made Easy Or the Young Clerks Assistant Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GEORGE BICKHAMS PENMANSHIP MADE EASY OR THE YOUNG CLERKS ASSISTANT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Bickham | 64 pages | 21 Jan 1998 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486297798 | English | New York, United States George Bickhams Penmanship Made Easy or the Young Clerks Assistant PDF Book Illustration Art. Add links. Learning to write Spencerian script. George Bickham the Elder was born near the end of the seventeenth century. July 13, at am. For what was meant to be a practical form of business handwriting, the round-hand scripts displayed in The Universal Penman feature a surprising number of flamboyant flourishes and decorative extensions. A complete volume of The Universal Penman published in London in might cost a few thousand dollars or more. Folio , detail. Prints and Multiples. American Fine Art. This was the work of George Bickham, a calligrapher and engraver who in took on the task of inviting the best scribes of his day to contribute examples of their finest handwriting, which would be engraved, published, and sold to subscribers as a series of 52 parts over a period of eight years. Collecting The specimen illustrates the beautiful flowing shaded letterforms based on ovals that typify this style of script. In the 18th century, writing masters taught handwriting to educated men and women, especially to men who would be expected to use it on a daily basis in commerce. Kelchner, He is Director of the Scripta Typographic Institute. A wonderful example of this script, penned by master penman HP Behrensmeyer is shown in Sample 4. Studio handbook : lettering : over pages, lettering, design and layouts, new alphabets. -

Fonts for Latin Paleography

FONTS FOR LATIN PALEOGRAPHY Capitalis elegans, capitalis rustica, uncialis, semiuncialis, antiqua cursiva romana, merovingia, insularis majuscula, insularis minuscula, visigothica, beneventana, carolina minuscula, gothica rotunda, gothica textura prescissa, gothica textura quadrata, gothica cursiva, gothica bastarda, humanistica. User's manual 5th edition 2 January 2017 Juan-José Marcos [email protected] Professor of Classics. Plasencia. (Cáceres). Spain. Designer of fonts for ancient scripts and linguistics ALPHABETUM Unicode font http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/alphabet.html PALEOGRAPHIC fonts http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/palefont.html TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page Table of contents 2 Introduction 3 Epigraphy and Paleography 3 The Roman majuscule book-hand 4 Square Capitals ( capitalis elegans ) 5 Rustic Capitals ( capitalis rustica ) 8 Uncial script ( uncialis ) 10 Old Roman cursive ( antiqua cursiva romana ) 13 New Roman cursive ( nova cursiva romana ) 16 Half-uncial or Semi-uncial (semiuncialis ) 19 Post-Roman scripts or national hands 22 Germanic script ( scriptura germanica ) 23 Merovingian minuscule ( merovingia , luxoviensis minuscula ) 24 Visigothic minuscule ( visigothica ) 27 Lombardic and Beneventan scripts ( beneventana ) 30 Insular scripts 33 Insular Half-uncial or Insular majuscule ( insularis majuscula ) 33 Insular minuscule or pointed hand ( insularis minuscula ) 38 Caroline minuscule ( carolingia minuscula ) 45 Gothic script ( gothica prescissa , quadrata , rotunda , cursiva , bastarda ) 51 Humanist writing ( humanistica antiqua ) 77 Epilogue 80 Bibliography and resources in the internet 81 Price of the paleographic set of fonts 82 Paleographic fonts for Latin script 2 Juan-José Marcos: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The following pages will give you short descriptions and visual examples of Latin lettering which can be imitated through my package of "Paleographic fonts", closely based on historical models, and specifically designed to reproduce digitally the main Latin handwritings used from the 3 rd to the 15 th century. -

From Law in Blackletter to “Blackletter Law”*

LAW LIBRARY JOURNAL Vol. 108:2 [2016-9] From Law in Blackletter to “Blackletter Law”* Kasia Solon Cristobal** Where does the phrase “blackletter law” come from? Chasing down its origins uncov- ers not only a surprising turnabout from blackletter law’s original meaning, but also prompts examination of a previously overlooked subject: the history of the law’s changing appearance on the page. This history ultimately provides a cautionary tale of how appearances have hindered access to the law. Introduction .......................................................181 What the Law Looked Like: The Lay of the Land .........................185 Handwriting .....................................................185 Print ...........................................................187 Difficulties in Reading the Law ........................................189 Handwriting .....................................................190 Print ...........................................................193 Why Gothic Persisted Longest in the Law ...............................195 Gothic’s Symbolism ...............................................196 State Authority .................................................198 National Identity ...............................................199 The Englishness of English Law ...................................201 Gothic’s Vested Interests. .203 Printers .......................................................204 Clerks ........................................................205 Lawyers .......................................................209 -

English Calligraphy Writing Pdf

English calligraphy writing pdf Continue Callile redirects here. For more information about novels, see The Booker. For more information, calligraphy Arabic chinese characters related to handwriting and script writing Georgian Indo-Islamic Japanese Korean Mongolian Vietnamese Vietnamese Western Western examples (from Greek: from the alpha alpha alpha) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of retarding with wide tip instruments, brushes, or other writing instruments. [1]17 Modern writing practices can be defined as techniques that give shape to billboards in a expressive, harmonious and skillful way. [1]18 Modern calligraphy ranges from functional inscriptions and designs to works of art where characters may or may not be readable. [1] [Need page] Classical calligraphy is different from typographic or non-classical handwriting, but calligraphers can practice both. [2] [3] [4] [5] Calligraphy continues to thrive in the form of wedding invitations and event invitations, font design and typography, original handwritten logo design, religious art, announcements, graphic design and consignment art, cut stone inscriptions and memorial documents. It is also used for movie and television props and videos, testimony, birth certificates, death certificates, maps, and other written works. [6] [7] Tools Calligraphy pens with calligraphy names, the main tools for callidists are pens and brushes. Calligraphy pens are written in nibs that may be flat, round, or sharp. [8] [9] For some decorative purposes, you can use a multi-nib pen (steel brush). However, some works are made of felt tips and ballpoint pens, but angled lines are not adopted. There are some calligraphy styles that require stub pens, such as Gothic scripts. -

Latin Paleography (Fonts for Latin Script)

FFFONTS FOR LATIN PPPALEOGRAPHY Capitalis elegans, capitalis rustica, uncialis, semiuncialis, antiqua cursiva romana, merovingia, insularis majuscula, insularis minuscula, visigothica, beneventana, carolina minuscula, gothica rotunda, gothica textura prescissa, gothica textura quadrata, gothica cursiva, gothica bastarda, humanistica. User's manual 4th edition June 2014 Juan-José Marcos [email protected] Professor of Classics. Plasencia. (Cáceres). Spain. Designer of fonts for ancient scripts and linguistics ALPHABETUM Unicode font http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/alphabet.html PALEOGRAPHIC fonts http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/palefont.html TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page Table of contents 2 Introduction 3 Epigraphy and Paleography 3 The Roman majuscule book-hand 4 Square Capitals (capitalis elegans) 5 Rustic Capitals (capitalis rustica) 8 Uncial script (uncialis) 10 Old Roman cursive (antiqua cursiva romana) 13 New Roman cursive (nova cursiva romana) 16 Half-uncial or Semi-uncial (semiuncialis) 19 Post-Roman scripts or national hands 22 Germanic script (scriptura germanica) 23 Merovingian minuscule (merovingia, luxoviensis minuscula) 24 Visigothic minuscule (visigothica) 27 Lombardic and Beneventan scripts (beneventana) 30 Insular scripts 33 Insular Half-uncial or Insular majuscule (insularis majuscula) 33 Insular minuscule or pointed hand (insularis minuscula) 38 Caroline minuscule (carolingia minuscula) 45 Gothic script (gothica prescissa, quadrata, rotunda, cursiva, bastarda) 51 Humanist writing (humanistica antiqua) 77 Epilogue 80 Bibliography and resources in the internet 81 Price of the paleographic set of fonts 82 Paleographic fonts for Latin script 2 Juan-José Marcos. [email protected] INTRODUCTION The following pages will give you short descriptions and visual examples of Latin lettering which can be imitated through my package of "Paleographic fonts", closely based on historical models, and specifically designed to reproduce digitally the main Latin handwritings used from the 3rd to the 15th century. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Lucie Koktavá The History of Cursive Handwriting in the United States of America Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A., Ph. D. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the sources listed in the bibliography. ....................................................... Lucie Koktavá Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A., Ph.D. for his guidance and advice. I am also grateful for the support of my family and my friends. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 1 The Description of Cursive Handwriting ............................................................. 8 1.1 Copperplate ..................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Spencerian Cursive Writing System ............................................................... 12 1.3 Palmer Method ................................................................................................ 15 1.4 D'Nealian ........................................................................................................ 17 2 The History of American Handwriting ............................................................... 19 2.1 The First Period of American Handwriting (1600–1800) .............................. 20 2.2 The Second Period -

A History of Learning to Write

9 A History of Learning to Write EWAN CLAYTON W I begin with a brief background account of the in the way handwriting is understood. Over the last origins of our present letterforms and how they half-century our knowledge of its history has developed arrived in England. This story has its starting point in in detail but not in perspective; new areas of scholar- Renaissance Italy; the Gothic hands of the Middle ship and technology are now changing that. Recent Ages, their origins in the twelfth century and the studies of the history of reading have opened our eyes Anglo-Saxon, early European and late Roman cursives to the sheer variety of ways in which we read; privately that came before them are a subject in their own right. or in public, skimming, reflectively, slowly and repeat- The focus here is on the sixteenth century, an extra- edly; in church, kitchen, library, train or bed. People ordinary period in which all our contemporary have not always read the same way; reading has a his- concerns about handwriting have their roots. Study tory. Handwriting, too, has a history and is practised of the intervening five centuries challenges the view in an equally rich diversity of ways. We write differ- that there is nothing more to be said than to list ently when we copy notes for revision or annotate writing masters and convey a vague feeling that it was the margins of a report, the handwriting on our tele- downhill all the way. In fact it was. An understanding phone pad is different from that in a letter of sym- of the origins of our present day scripts helps us to pathy or on a birthday card, the draft of a poem or see that the sub-text underlying most discussions on the cheque written at the supermarket checkout is handwriting is our changing definitions of what it is yet again different from the ‘printing’ on our tax to be human. -

Ornamental Penmanship

Dr. Joseph M. Vitolo’s Record of Contributions to the Art & History of Ornamental Penmanship 1 February 26, 2021 Dear friends, I have spent many years searching and documenting the art, techniques and historical information of the pointed pen art form. I proceed in the footsteps of those who came before me that have added greatly to our knowledge base. In 2015, I decided to document, or at least to put into perspective my own contributions to the pointed pen art form. The result of that effort was this document. While these pages do not contain a complete list, they do represent the majority of my efforts on behalf of Ornamental Penmanship and the pointed pen art form in general. It is my hope that this document will serve as a roadmap to those seeking this information in cyberspace. It gives me great satisfaction to know that pen artists around the globe now know the art and contribution of penmen such as Lupfer, Madarasz and Zaner. I am convinced that the spark many of us have seeded over the years has now become a raging fire. I am often asked, “Why do you give it all away?” The answer is very simple. I was a novice once too and it is my way of repaying the extraordinary kindness and generosity that I was shown at my first IAMPETH Convention way back in 1999. The quote of Pablo Picasso on page 3 of this document best sums up my thoughts on this matter. All I ask in return from anyone that has enjoyed/benefitted from the materials I provided is that you ‘Pay it Forward’ if you get the chance to help someone who is struggling in calligraphy or in life. -

An Investigation Into the Growing Popularity of Script Typefaces and the Technical Means by Which They Are Created Today Yacotzin Alva

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 5-1-1997 An Investigation into the growing popularity of script typefaces and the technical means by which they are created today Yacotzin Alva Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Alva, Yacotzin, "An Investigation into the growing popularity of script typefaces and the technical means by which they are created today" (1997). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute ofTechnology SCHOOL OF PRINTING MANAGEMENT AND SCIENCES An Investigation into the Growing Popularity of Script Typefaces and the Technical Means by which They are Created Today. A thesis project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the School of Printing Management and Sciences of the College of Imaging Arts and Sciences of the Rochester Institute ofTechnology Yacotzin Alva Thesis Advisor: David Pankow Technical Advisor: Archibald Provan Rochester, New York School of Printing Management and Sciences Rochester Institute ofTechnology Rochester, New York Certificate ofApproval Master's Thesis This is to certify that the Master's Thesis of Yacotzin Alva With a major in Graphic Arts Publishing has been approved by the Thesis Committee as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the Master of Science degree at the convocation of May, I997 Thesis Committee: David Pankow Thesis Advisor Marie Freckleton Graduate Pro am Coordinator Director or,Designate An Investigation into the Growing Popularity of Script Typefaces and the Technical Means by which They are Created Today.