Oakambrosiabeetle.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genomic Signals of Adaptation Towards Mutualism and Sociality in Two Ambrosia Beetle Complexes

life Article Genomic Signals of Adaptation towards Mutualism and Sociality in Two Ambrosia Beetle Complexes Jazmín Blaz 1, Josué Barrera-Redondo 2, Mirna Vázquez-Rosas-Landa 1, Anahí Canedo-Téxon 1, Eneas Aguirre von Wobeser 3 , Daniel Carrillo 4, Richard Stouthamer 5, Akif Eskalen 6, Emanuel Villafán 1, Alexandro Alonso-Sánchez 1, Araceli Lamelas 1 , Luis Arturo Ibarra-Juarez 1,7 , Claudia Anahí Pérez-Torres 1,7 and Enrique Ibarra-Laclette 1,* 1 Red de Estudios Moleculares Avanzados, Instituto de Ecología A.C, Xalapa, Veracruz 91070, Mexico; [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (M.V.-R.-L.); [email protected] (A.C.-T.); [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (A.A.-S.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (L.A.I.-J.); [email protected] (C.A.P.-T.) 2 Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México 04500, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Cátedras CONACyT/Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, Hermosillo 83304, Mexico; [email protected] 4 Tropical Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Homestead, FL 33031, USA; dancar@ufl.edu 5 Department of Plant Pathology, University of California–Riverside, Riverside, CA 92521, USA; [email protected] 6 Department of Plant Pathology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616-8751, USA; [email protected] 7 Cátedras CONACyT/Instituto de Ecología A.C., Xalapa, Veracruz 91070, Mexico * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-(228)-842-18-00 Received: 14 October 2018; Accepted: 20 December 2018; Published: 22 December 2018 Abstract: Mutualistic symbiosis and eusociality have developed through gradual evolutionary processes at different times in specific lineages. -

Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in Old-Growth Northwest Forests'

AMER. ZOOL., 33:578-587 (1993) Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in Old-Growth mon et al., 1990; Hz Northwest Forests complex litter layer 1973; Lattin, 1990; JOHN D. LATTIN and other features Systematic Entomology Laboratory, Department of Entomology, Oregon State University, tural diversity of th Corvallis, Oregon 97331-2907 is reflected by the 14 found there (Lawtt SYNOPSIS. Old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest extend along the 1990; Parsons et a. e coastal region from southern Alaska to northern California and are com- While these old posed largely of conifer rather than hardwood tree species. Many of these ity over time and trees achieve great age (500-1,000 yr). Natural succession that follows product of sever: forest stand destruction normally takes over 100 years to reach the young through successioi mature forest stage. This succession may continue on into old-growth for (Lattin, 1990). Fire centuries. The changing structural complexity of the forest over time, and diseases, are combined with the many different plant species that characterize succes- bances. The prolot sion, results in an array of arthropod habitats. It is estimated that 6,000 a continually char arthropod species may be found in such forests—over 3,400 different ments and habitat species are known from a single 6,400 ha site in Oregon. Our knowledge (Southwood, 1977 of these species is still rudimentary and much additional work is needed Lawton, 1983). throughout this vast region. Many of these species play critical roles in arthropods have lx the dynamics of forest ecosystems. They are important in nutrient cycling, old-growth site, tt as herbivores, as natural predators and parasites of other arthropod spe- mental Forest (HJ cies. -

MYCOTAXON Volume 104, Pp

MYCOTAXON Volume 104, pp. 399–404 April–June 2008 Raffaelea lauricola, a new ambrosia beetle symbiont and pathogen on the Lauraceae T. C. Harrington1*, S. W. Fraedrich2 & D. N. Aghayeva3 *[email protected] 1Department of Plant Pathology, Iowa State University 351 Bessey Hall, Ames, IA 50011, USA 2Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service Athens, GA 30602, USA 3Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences Patamdar 40, Baku AZ1073, Azerbaijan Abstract — An undescribed species of Raffaelea earlier was shown to be the cause of a vascular wilt disease known as laurel wilt, a severe disease on redbay (Persea borbonia) and other members of the Lauraceae in the Atlantic coastal plains of the southeastern USA. The pathogen is likely native to Asia and probably was introduced to the USA in the mycangia of the exotic redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus. Analyses of rDNA sequences indicate that the pathogen is most closely related to other ambrosia beetle symbionts in the monophyletic genus Raffaelea in the Ophiostomatales. The asexual genus Raffaelea includes Ophiostoma-like symbionts of xylem-feeding ambrosia beetles, and the laurel wilt pathogen is named R. lauricola sp. nov. Key words — Ambrosiella, Coleoptera, Scolytidae Introduction A new vascular wilt pathogen has caused substantial mortality of redbay [Persea borbonia (L.) Spreng.] and other members of the Lauraceae in the coastal plains of South Carolina, Georgia, and northeastern Florida since 2003 (Fraedrich et al. 2008). The fungus apparently was introduced to the Savannah, Georgia, area on solid wood packing material along with the exotic redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus Eichhoff (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae), a native of southern Asia (Fraedrich et al. -

Appl. Entomol. Zool. 41 (1): 123–128 (2006)

Appl. Entomol. Zool. 41 (1): 123–128 (2006) http://odokon.ac.affrc.go.jp/ Death of Quercus crispula by inoculation with adult Platypus quercivorus (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) Haruo KINUURA1,* and Masahide KOBAYASHI2 1 Kansai Research Center, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute; Kyoto 612–0855, Japan 2 Kyoto Prefectural Forestry Experimental Station; Kyoto 629–1121, Japan (Received 10 December 2004; Accepted 27 October 2005) Abstract Adult Platypus quercivorus beetles were artificially inoculated into Japanese oak trees (Quercus crispula). Two inocu- lation methods were used: uniform inoculation through pipette tips, and random inoculation by release into netting. Four of the five trees that were inoculated uniformly died, as did all five trees that were inoculated at random. Seven of the nine dead trees showed the same wilting symptoms seen in the current mass mortality of oak trees. Raffaelea quercivora, which has been confirmed to be the pathogenic fungus that causes wilt disease and is usually isolated from the mycangia of P. quercivorus, was isolated from all of the inoculated dying trees. Trees that died faster showed a higher density of beetle galleries that succeeded in producing offspring. We found positive relationships between the density of beetle galleries that succeeded in producing offspring and the rate of discoloration in the sapwood and the isolation rate of R. quercivora. Therefore, we clearly demonstrated that P. quercivorus is a vector of R. quercivora, and that the mass mortality of Japanese oak trees is caused by mass attacks of P. quercivorus. Key words: Mass mortality; oak; pathogenic fungi; Raffaelea quercivora; vector An inoculation test on some smaller trees in the INTRODUCTION nursery with this fungus, which was later described In Japan, the mass mortality of oak trees (Quer- as Raffaelea quercivora Kubono et Shin. -

Fungus-Farming Insects: Multiple Origins and Diverse Evolutionary Histories

Commentary Fungus-farming insects: Multiple origins and diverse evolutionary histories Ulrich G. Mueller* and Nicole Gerardo* Section of Integrative Biology, Patterson Laboratories, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 bout 40–60 million years before the subterranean combs that the termites con- An even richer picture emerges when com- Aadvent of human agriculture, three in- struct within the heart of nest mounds (11). paring termite fungiculture to two other sect lineages, termites, ants, and beetles, Combs are supplied with feces of myriads of known fungus-farming insects, attine ants independently evolved the ability to grow workers that forage on wood, grass, or and ambrosia beetles, which show remark- fungi for food. Like humans, the insect leaves (Fig. 1d). Spores of consumed fungus able evolutionary parallels with fungus- farmers became dependent on cultivated are mixed with the plant forage in the ter- growing termites (Fig. 1 a–c). crops for food and developed task-parti- mite gut and survive the intestinal passage tioned societies cooperating in gigantic ag- (11–14). The addition of a fecal pellet to the Ant and Beetle Fungiculture. In ants, the ricultural enterprises. Agricultural life ulti- comb therefore is functionally equivalent to ability to cultivate fungi for food has arisen mately enabled all of these insect farmers to the sowing of a new fungal crop. This unique only once, dating back Ϸ50–60 million years rise to major ecological importance. Indeed, fungicultural practice enabled Aanen et al. ago (15) and giving rise to roughly 200 the fungus-growing termites of the Old to obtain genetic material of the cultivated known species of fungus-growing (attine) World, the fungus-growing ants of the New fungi directly from termite guts, circumvent- ants (4). -

Litteratura Coleopterologica (1758–1900)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 583: 1–776 (2016) Litteratura Coleopterologica (1758–1900) ... 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.583.7084 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Litteratura Coleopterologica (1758–1900): a guide to selected books related to the taxonomy of Coleoptera with publication dates and notes Yves Bousquet1 1 Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Central Experimental Farm, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6, Canada Corresponding author: Yves Bousquet ([email protected]) Academic editor: Lyubomir Penev | Received 4 November 2015 | Accepted 18 February 2016 | Published 25 April 2016 http://zoobank.org/01952FA9-A049-4F77-B8C6-C772370C5083 Citation: Bousquet Y (2016) Litteratura Coleopterologica (1758–1900): a guide to selected books related to the taxonomy of Coleoptera with publication dates and notes. ZooKeys 583: 1–776. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.583.7084 Abstract Bibliographic references to works pertaining to the taxonomy of Coleoptera published between 1758 and 1900 in the non-periodical literature are listed. Each reference includes the full name of the author, the year or range of years of the publication, the title in full, the publisher and place of publication, the pagination with the number of plates, and the size of the work. This information is followed by the date of publication found in the work itself, the dates found from external sources, and the libraries consulted for the work. Overall, more than 990 works published by 622 primary authors are listed. For each of these authors, a biographic notice (if information was available) is given along with the references consulted. Keywords Coleoptera, beetles, literature, dates of publication, biographies Copyright Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. -

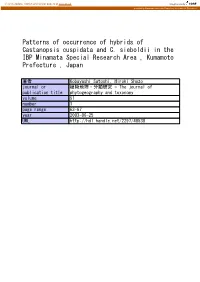

Patterns of Occurrence of Hybrids of Castanopsis Cuspidata and C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kanazawa University Repository for Academic Resources Patterns of occurrence of hybrids of Castanopsis cuspidata and C. sieboldii in the IBP Minamata Special Research Area , Kumamoto Prefecture , Japan 著者 Kobayashi Satoshi, Hiroki Shozo journal or 植物地理・分類研究 = The journal of publication title phytogeography and toxonomy volume 51 number 1 page range 63-67 year 2003-06-25 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2297/48538 Journal of Phytogeography and Taxonomy 51 : 63-67, 2003 !The Society for the Study of Phytogeography and Taxonomy 2003 Satoshi Kobayashi and Shozo Hiroki : Patterns of occurrence of hybrids of Castanopsis cuspidata and C. sieboldii in the IBP Minamata Special Research Area , Kumamoto Prefecture , Japan Graduate School of Human Informatics, Nagoya University, Chikusa-Ku, Nagoya 464―8601, Japan Castanopsis cuspidata(Thunb.)Schottky and However, it is difficult to identify the hybrids by C. sieboldii(Makino)Hatus. ex T. Yamaz. et nut morphology alone, because the nut shapes of Mashiba are dominant components of the ever- the 2 species are variable and can overlap with green broad-leaved forests of southwestern Ja- each other. Kobayashi et al.(1998)showed that pan, including parts of Honshu, Kyushu and hybrids have a chimeric structure of both 1 and Shikoku but excluding the Ryukyu Islands(Hat- 2 epidermal layers within a leaf. These morpho- tori and Nakanishi 1983).Although these 2 Cas- logical differences among C. cuspidata, C. sie- tanopsis species are both climax species, it is boldii and their hybrid can be confirmed by ge- very difficult to distinguish them because of the netic differences in nuclear species-specific existence of an intermediate type(hybrid). -

Report of a Pest Risk Analysis for Platypus Parallelus (Fabricus, 1801) for Turkey

Bulletin OEPP/EPPO Bulletin (2015) 45 (1), 112–118 ISSN 0250-8052. DOI: 10.1111/epp.12190 Report of a pest risk analysis for Platypus parallelus (Fabricus, 1801) for Turkey E. M.Gum€ us€ß and A. Ergun€ Izmir_ Agricultural Quarantine Directorate, PO 35230, Konak, Izmir,_ Turkey; e-mail: [email protected] Invasive bark and ambrosia beetles (Curculionidae: Scolytinae and Platypodinae) are increasingly responsible for damage to forests, plantations and orchards worldwide. They are usually closely associated with fungi, which may be pathogenic causing tree mortal- ity. Stressed or weakened trees are particularly subject to attack, as is recently felled, non-treated wood. This PRA report concerns the ambrosia beetle Platypus parallelus (Euplatypus parallelus, Fabricus, 1801) (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), which was detected in official controls. The PRA area is Turkey. P. parallelus is not on the A1 or A2 list for Turkey but the Regulation on Plant Quarantine (3 December 2011-OJ no: 28131) Article 13 (5) indicates that pests which are assessed to pose a risk for Turkey following PRA that are not present in the above lists and plants, wood, plant products and other mate- rials contaminated by these organisms are banned from entry into Turkey. This risk assessment follows the EPPO Standard PM 5/3(5) Decision-support scheme for quarantine pests and uses the terminology defined in ISPM 5 Glossary of Phytosanitary Terms. This paper addresses the possible risk factors caused by Platypus parallelus (Euplatypus parallelus, Fabricus, 1801) in Turkey. Terms (available at https://www.ippc.int/index.php). The Introduction PRA area is Turkey. -

Continued Eastward Spread of the Invasive Ambrosia Beetle Cyclorhipidion Bodoanum (Reitter, 1913) in Europe and Its Distribution in the World

BioInvasions Records (2021) Volume 10, Issue 1: 65–73 CORRECTED PROOF Rapid Communication Continued eastward spread of the invasive ambrosia beetle Cyclorhipidion bodoanum (Reitter, 1913) in Europe and its distribution in the world Tomáš Fiala1,*, Miloš Knížek2 and Jaroslav Holuša1 1Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic 2Forestry and Game Management Research Institute, Prague, Czech Republic *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Fiala T, Knížek M, Holuša J (2021) Continued eastward spread of the Abstract invasive ambrosia beetle Cyclorhipidion bodoanum (Reitter, 1913) in Europe and its Ambrosia beetles, including Cyclorhipidion bodoanum, are frequently introduced into distribution in the world. BioInvasions new areas through the international trade of wood and wood products. Cyclorhipidion Records 10(1): 65–73, https://doi.org/10. bodoanum is native to eastern Siberia, the Korean Peninsula, Northeast China, 3391/bir.2021.10.1.08 Southeast Asia, and Japan but has been introduced into North America, and Europe. Received: 4 August 2020 In Europe, it was first discovered in 1960 in Alsace, France, from where it has slowly Accepted: 19 October 2020 spread to the north, southeast, and east. In 2020, C. bodoanum was captured in an Published: 5 January 2021 ethanol-baited insect trap in the Bohemian Massif in the western Czech Republic. The locality is covered by a forest of well-spaced oak trees of various ages, a typical Handling editor: Laura Garzoli habitat for this beetle. The capture of C. bodoanum in the Bohemian Massif, which Thematic editor: Angeliki Martinou is geographically isolated from the rest of Central Europe, confirms that the species Copyright: © Fiala et al. -

Australia's Biodiversity and Climate Change

Australia’s Biodiversity and Climate Change A strategic assessment of the vulnerability of Australia’s biodiversity to climate change A report to the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council commissioned by the Australian Government. Prepared by the Biodiversity and Climate Change Expert Advisory Group: Will Steffen, Andrew A Burbidge, Lesley Hughes, Roger Kitching, David Lindenmayer, Warren Musgrave, Mark Stafford Smith and Patricia A Werner © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 ISBN 978-1-921298-67-7 Published in pre-publication form as a non-printable PDF at www.climatechange.gov.au by the Department of Climate Change. It will be published in hard copy by CSIRO publishing. For more information please email [email protected] This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General's Department 3-5 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] Or online at: http://www.ag.gov.au Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for Climate Change and Water and the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts. Citation The book should be cited as: Steffen W, Burbidge AA, Hughes L, Kitching R, Lindenmayer D, Musgrave W, Stafford Smith M and Werner PA (2009) Australia’s biodiversity and climate change: a strategic assessment of the vulnerability of Australia’s biodiversity to climate change. -

Screening Aid Platypus Quercivorus (Murayama), Megaplatypus Mutatus (Chapuis)

Ambrosia Beetles Screening Aid Platypus quercivorus (Murayama), Megaplatypus mutatus (Chapuis) Joseph Benzel 1) Identification Technology Program (ITP) / Colorado State University, USDA-APHIS-PPQ-Science & Technology (S&T), 2301 Research Boulevard, Suite 108, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 U.S.A. (Email: [email protected]) This CAPS (Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey) screening aid produced for and distributed by: Version 5 USDA-APHIS-PPQ National Identification Services (NIS) 30 June 2015 This and other identification resources are available at: http://caps.ceris.purdue.edu/taxonomic_services The ambrosia beetles (Platypodinae) (Fig. 1) are an enigmatic group of bark beetles native to the tropical regions of the world. Within this group two species are considered potentially invasive pests: Platypus quercivorus (Murayama) and Megaplatypus mutatus (Chapuis). Platypus quercivorus feeds primarily on oaks (Quercus) and other broad leaf trees and spreads the ambrosia fungus Raffaelea quercivora which may be the agent of Japanese oak disease. Megaplatypus mutatus primarily attacks walnut (Juglans), poplar (Populus), and apple (Malus) trees but will infest a variety of other broadleaf trees. It does little direct damage to the tree, but its boring can reduce the tree’s structural integrity and discoloration caused by symbiotic fungi reduce wood quality (Figs. 2-3). Platypodinae is currently considered a subfamily of Curculionidae which Fig. 1: Platypus sp. on tree (photo by, is comprised of weevils and bark beetles. Members of this family are Andrea Battisti, Universita di Padova, highly variable but almost all species share a distinct club on the end Bugwood.org). of their antennae consisting of three segments. In general, members of Platypodinae are small (<10mm long) elongate beetles of a reddish brown or black color. -

Holocene Palaeoenvironmental Reconstruction Based on Fossil Beetle Faunas from the Altai-Xinjiang Region, China

Holocene palaeoenvironmental reconstruction based on fossil beetle faunas from the Altai-Xinjiang region, China Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London By Tianshu Zhang February 2018 Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London Declaration of Authorship I Tianshu Zhang hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 25/02/2018 1 Abstract This project presents the results of the analysis of fossil beetle assemblages extracted from 71 samples from two peat profiles from the Halashazi Wetland in the southern Altai region of northwest China. The fossil assemblages allowed the reconstruction of local environments of the early (10,424 to 9500 cal. yr BP) and middle Holocene (6374 to 4378 cal. yr BP). In total, 54 Coleoptera taxa representing 44 genera and 14 families have been found, and 37 species have been identified, including a new species, Helophorus sinoglacialis. The majority of the fossil beetle species identified are today part of the Siberian fauna, and indicate cold steppe or tundra ecosystems. Based on the biogeographic affinities of the fossil faunas, it appears that the Altai Mountains served as dispersal corridor for cold-adapted (northern) beetle species during the Holocene. Quantified temperature estimates were made using the Mutual Climate Range (MCR) method. In addition, indicator beetle species (cold adapted species and bark beetles) have helped to identify both cold and warm intervals, and moisture conditions have been estimated on the basis of water associated species.