At the COP – Global Climate Justice Youth Speak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Solutions” Issue, Spring 2008 Change Our Sources of Electricity Arjun Makhijani Is an Engineer Who’S Been Thinking About Energy for More Than 35 Years

Powerful Ideas, Climate PractIcal actIons Solutions Special Issue Stop Global yes!sPrIng 2008 Warming Bill McKibben: It’s Not Too Late to Save the World 13 Best Ideas in Clean Energy (Plus a Few Duds) How Your Family Can Get Carbon Free in 10 Years The Secret Life of Plug-in Cars Author and climate activist Bill McKibben at home in Vermont Surprise Victory for Global Fairness “One way or another, the choice will be made by our generation, but it will affect life on earth for all generations to come.” Lester Brown , Earth Policy Institute Tsewang Norbu was selected by his Himalayan village to be trained at the Barefoot College of Tilonia, India, in the installation and repair of solar photovoltaic units. All solar units were brought to the village across the 18,400- foot Khardungla Pass by yak and on villagers’ backs. photo by barefoot photographers of tilonia. copyright 2008 barefoot college, tilonia, rajastan, india, barefootcollege.org yesm a g a z i! n e www.yesmagazine.org Reprinted from the “Climate Solutions” Issue, Spring 2008 Change Our Sources of Electricity Arjun Makhijani is an engineer who’s been thinking about energy for more than 35 years. When he heard a presentation ISSUE 45 claiming we needed to go fossil-carbon free by 2050, he didn’t YES! THEME GUIDE think it could be done. X years of research later, he’s changed his mind. His book, Carbon-Free and Nuclear-Free: A Roadmap for U.S. Energy Policy, tells exactly how it can be done. Here’s how Makhijani sees the energy supply changing for buildings, CLIMATE SOLUTIONStransportation and electricity. -

Sustainable Development Goals

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS DEVELOPMENT GOALS SUSTAINABLE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS | TRANSFORMING OUR WORLD Transforming our world CONTRIBUTORS INCLUDE María Fernanda Espinosa Achim Steiner | Henrietta Fore Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka Michelle Bachelet | Mark Lowcock Mukhisa Kituyi | Devi Sridhar Louis Charbonneau | Liu Zhenmin Ellen MacArthur | Edward Barbier Jonathan Glennie | Lysa John HERMES SDG ENGAGEMENT Aiming to generate outcomes that benefi t people, the planet and investors, through investments aligned with the UN SDGs We are committed to supporting the UN SDGs and engage with businesses to encourage their adoption. It is our belief that the enduring success of companies is intertwined with that of the economies, communities and environments in which they operate. Visit www.hermes-investment.com The value of investments and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount invested. For Professional Investors only. Issued and approved by Hermes Investment Management Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered address: Sixth fl oor, 150 Cheapside, London EC2V 6ET. Telephone calls will be recorded for training and monitoring purposes. Hermes.indd0005957_SDG_Engagement_Fund_Press_276x210.indd 1 1 03/06/201910/04/2019 22:0113:58 CONTENTS 3 Contents FOREWORDS 20 What to expect from the new champions Where action by national governments on SDG 8 The 2030 Agenda: our answer to the naysayers implementation is lacking, can others fill the void? By María Fernanda Espinosa, By Adriana Erthal Abdenur President, 73rd session, United Nations General Assembly 24 Human development and the SDGs 10 Cooperation can change everything UNDP’s Human Development Report turns 30 next year. -

2019 (November 2018 – October 2019)

QUAKER EARTHCARE WITNESS ANNUAL REPORT November 2018 - October 2019 Affirming our essential unity with nature Above: Friends visit Jim and Kathy Kessler’s restored native plant habitat during the Friends General Conference Gathering in Iowa. OUR WORK THIS YEAR Quaker Earthcare Witness has grown over the last 32 years out of a deepening sense of QUAKER ACTIVISM & spiritual connection with the natural world. From this has come an urgency to work on the critical EDUCATION issues of our times, including climate and environmental justice. This year we are excited to see that more people This summer we sponsored the QEW Earthcare Center are mobilizing around the eco-crises than ever before, at the Friends General Conference annual gathering, both within and beyond the Religious Society of Friends. including scheduling and hosting presentations every afternoon, showcasing what Friends are doing regarding With your help, Quaker Earthcare Witness is Earthcare, displaying resources to share, and giving responding to the growing need for inspiration talks. We offered presentations on climate justice, and support for Friends and Meetings. indigenous concerns, eco-spirituality, activism and hope, permaculture, and children’s education. We also QEW is the largest network of Friends working on sponsored a field trip to a restored prairie (thanks to Jim Earthcare today. We work to inspire spirit-led action Kessler, QEW Steering Committee member, who planned toward ecological sustainability and environmental the trip and restored, along with his wife Kathy, this plot justice. We provide inspiration and resources to Friends of Iowa prairie). throughout North America by distributing information in our newsletter, BeFriending Creation, on our website Our General Secretary, Communications Coordinator, quakerearthcare.org and through social media. -

The Time to Act Is

The Time to Act is Now Grassroots Multi-Faith Action for the Earth Introduction Religious communities are at a crossroads with our response to climate change and other imminent threats to the environment. For much of the past 15 years, religious communities’ primary focus has been education and awareness raising on climate change, teaching that our faiths and their central teachings apply not only between people and to the Sacred, but person to planet. That education, while still vital, is not enough. We must take bold public action. We’ve seen the magnitude of the crisis. We know that public action at scale is absolutely essential. On 11 March, 2021, diverse religious and spiritual communities in 49 countries carried out 420 actions to draw attention to the climate crisis. The Sacred People, Sacred Earth day of action was organized by a grassroots, global, multi-faith alliance called the GreenFaith International Network. You can experience the energy and passion of these actions by watching this short video on Sacred People, Sacred Earth. Around Earth Day in April and World Environment Day in June, religious and spiritual leaders around the world often offer a sermon, khutbah, dharma teaching, dvar torah, or other spoken message on the climate crisis. The religious or spiritual gatherings around these days, and every gathering of its kind, offers an opportunity to convey how our different faiths compel us to take bold action on climate change. The actions organized by grassroots people of diverse faiths worldwide, a few of which are featured in this document, offer powerful instructional examples of religious belief in action, examples which can help pastors, imams, gurus, priests, rabbis, and other spiritual leaders bring to life the importance of public, morally-rooted action on climate change. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Promoting Lower-Carbon Lifestyles: The role of personal values, climate change communications and carbon allowances in processes of change Rachel Angharad Howell Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2012 1 Declaration This thesis and the papers within it have been composed by me and are my own work, except where otherwise stated. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or qualification. Rachel Howell September 2012 1 2 Abstract Climate change is a pressing problem and substantial reductions in the greenhouse gas emissions that cause it are necessary to avert the worst impacts predicted. The UK has targeted an 80% reduction from 1990 emissions levels by 2050. This thesis investigates how to promote behavioural changes that will reduce emissions associated with individuals’ lifestyles, which comprise a significant proportion of the UK total. -

Howell Aos Paper 1

Edinburgh Research Explorer Lights, camera ... action? Altered attitudes and behaviour in response to the climate change film The Age of Stupid Citation for published version: Howell, RA 2011, 'Lights, camera ... action? Altered attitudes and behaviour in response to the climate change film The Age of Stupid', Global Environmental Change, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 177-187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.09.004 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.09.004 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Global Environmental Change General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Lights, camera … action? Altered attitudes and behaviour in response to the climate change film The Age of Stupid Rachel A. Howell Email address: [email protected] Abstract The film The Age of Stupid depicts the world in 2055 devastated by climate change, combining this with documentary footage which illustrates many facets of the problems of climate change and fossil-fuel dependency. -

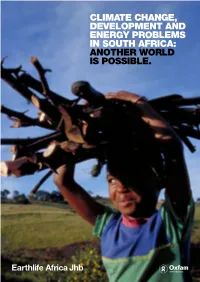

Climate Change, Development and Energy Problems in South Africa: Another World Is Possible

CLIMATE CHANGE, DEVELOPMENT AND ENERGY PROBLEMS IN SOUTH AFRICA: ANOTHER WORLD IS POSSIBLE. Earthlife Africa Jhb Earthlife Africa Jhb 20 CONTENTS Abbreviations 1 Foreword 2 Executive summary 4 Introduction 8 The long road to realising change 10 South Africa’s dilemma 14 Climate change in South Africa 17 The face of climate change 24 Is government response to climate change adequate? 29 The obstacles 34 Another world is possible 37 Conclusion 45 Afterword 47 Bibliography 48 ABBREVIATIONS Asgisa Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa BCLMP Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Programme CDM Clean Development Mechanism CDP Carbon Disclosure Project CO2 Carbon Dioxide CTL Coal to Liquid DEAT Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism GDP Gross Domestic Product GEAR Growth, Employment and Redistribution Strategy GHG Greenhouse gases GWC Growth Without Constraints GWh Gigawatt hour HLG High Level Group IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change JSE Johannesburg Securities Exchange KWh Kilowatt hour LTMS Long Term Mitigation Scenarios NCCS National Climate Change Strategy NEMA National Environmental Management Act NGO Non-governmental Organisation OCGT Open-Cycle Gas Turbines RBS Required By Science RDP Reconstruction and Development Programme TAC Treatment Action Campaign UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change 1 FOREWORD The scientific verdict is in; our planet is heating up and human activity is the cause. We already see indications of a dire future, with the Arctic ice sheet melting at rates faster than scientists predicted, and methane already bubbling up from the ocean floor. In South Africa, we already see changes in species distribution patterns, and indications of changes to wind and rainfall patterns. -

Children and Youth in the Climate Crisis Ann Sanson,1 Marco Bellemo2

EDITORIAL Children and youth in the climate crisis Ann Sanson,1 Marco Bellemo2 BJPsych Bulletin (2021) 45, 205–209, doi:10.1192/bjb.2021.16 1Department of Paediatrics, University of Summary This editorial is co-written by a developmental psychologist and a young 2 Melbourne, Australia; School Strike For climate activist. We start by showing how the climate crisis is imposing a heavy Climate, Australia psychological burden on children and youth, both from experiencing climate-related Correspondence to Ann Sanson disasters and from the knowledge that worse is to come. We then describe the global ([email protected]) movement of youth demanding urgent climate action. We conclude that health First received 23 Sep 2020, final revision 19 Jan 2021, accepted 28 Jan 2021 professionals can support young people in many ways, but particularly by supporting their capacity to take action, raising awareness about the impact of the climate crisis © The Authors 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of on youth mental and physical health, and taking action themselves to work for a the Royal College of Psychiatrists. This is secure climate future. an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Keywords Post-traumatic stress disorder; anxiety disorders; climate change; Commons Attribution licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4. childhood experience; developmental disorders. 0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The climate crisis poses an existential threat by the Global North, also referred to as high-income coun- tries, the minority world or the WEIRD nations (Western, Climate change is well underway and poses a critical threat educated, industrialised, rich democracies), comprising 12% to the future. -

Duane Elgin Endorsements for Choosing Earth “Choosing Earth Is the Most Important Book of Our Time

CHOOSING EARTH Humanity’s Great Transition to a Mature Planetary Civilization Duane Elgin Endorsements for Choosing Earth “Choosing Earth is the most important book of our time. To read and dwell within it is an awakening experience that can activate both an ecological and spiritual revolution.” —Jean Houston, PhD, Chancellor of Meridian University, philosopher, author of The Possible Human, Jump Time, Life Force and many more. “A truly essential book for our time — from one of the greatest and deepest thinkers of our time. Whoever is concerned to create a better future for the human family must read this book — and take to heart the wisdom it offers.” —Ervin Laszlo is evolutionary systems philosopher, author of more than one hundred books including The Intelligence of the Cosmos and Global Shift. “This may be the perfect moment for so prophetic a voice to be heard. Sobered by the pandemic, we are recognizing both the fragility of our political arrangements and the power of our mutual belonging. As Elgin knows, we already possess the essential ingredient —our capacity to choose.” —Joanna Macy, author of Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We're in Without Going Crazy, is root teacher of the Work That Reconnects and celebrated in A Wild Love for the World: Joanna Macy and the Work of Our Time. “Duane Elgin has thought hard — and meditated long — about what it will take for humanity to evolve past our looming ecological bottleneck toward a future worth building. There is wisdom in these pages to light the way through our dark and troubled times.” —Richard Heinberg is one of the world’s foremost advocates for a shift away from reliance on fossil fuels; author of Our Renewable Future, Peak Everything, and The End of Growth. -

Bill Mckibben

Bill McKibben The US environmentalist and founder of 350.org interviewed by Huw Spanner over the internet 22 June 2016 2 Bill McKibben | High Profiles | 22 June 2016 Time We Started Counting! Bill McKibben made his name as an environmentalist in 1989 with his ground- breaking ‘righteous jeremiad’ The End of Nature. Nineteen years later, an ‘unlikely activist’, he founded the global pressure group 350.org with seven of his students. Huw Spanner spoke to him over the internet. PHOTOGRAPHY: WOLFGANG SCHMIDT/RIGHT LIVELIHOOD AwARD When did you first become interested in environmentalism? I certainly knew about environmental issues growing up, though they weren’t my main concern – I was more interested in things like homelessness. When I was a young man I was on the staff of the New Yorker and I wrote a long piece for the magazine – I must have been 24 or something – about where everything in my apartment in New York City came from. They sent me off for a year, all over the world, to follow everything back to its ultimate source. So, I was in the Brazilian jungle looking at oil wells and I was up in the Arctic looking at the huge hydro dams at the tip of Hudson Bay and I was out on the barges that carry the city’s sewage out to sea and so on. And this had for me the interesting intellectual effect of making me realise how physical 3 Bill McKibben | High Profiles | 22 June 2016 the world actually was. I’d grown up in a good American suburb and a suburb is kind of a device for hiding out of sight all the physical workings of the planet. -

Fighting Inequalities Campaign TOOLKIT

Fighting Inequalities Campaign TOOLKIT The future of Europe and the achievement of the SDGs will be possible only if we end extreme inequalities and leave no one behind. This is a public mobilization, communication, and advocacy campaign. In line with the universal and inclusive approach reflected in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the campaign will connect the inequalities experienced by people locally, in all sorts of communities, with the national, European, and, ultimately, the global inequalities faced by billions. We want societal change for everyone, everywhere by 2030! See the campaign video. See the ‘17 steps to equality’ game. Our Goals? 1. Public awareness and public pressure to reduce inequalities 2. Raising citizens’ and decision makers’ awareness 3. Campaigning for collective action on implementing and monitoring of SDG 10 4. Advocating that the EU and its Members take concrete measures 5. Strengthening civil society #FightInequalities Content What do we want to achieve? 2 Timeline of Campaign – Key moments 3 SDG Action Week & Global Day of Action - 25 September 2018 4 Actions – What can you do? 5 Individuals & inequalities – What are people’s challenges? 5 Raising awareness and influencing decision-makers 6 Media and Social media campaigns 10 Tools 11 Factsheets and Infographics 11 #FightInequalities Fight Inequalities Campaign Page 1 of 10 What do we want to achieve? The Fighting Inequalities Campaign seeks to create awareness and promote the SDGs among citizens AND to help you to hold our governments accountable. In the last years, countries around the world - including EU MemBer States - have shown significant gaps Between policy commitments and implementation, especially in the fields of economic justice, human rights, social protection, gender equality and environmental protection. -

Next Global Action On

FTT/Robin Hood Tax Proposal for Global Day of Action 17th February 2011 Introduction Over the last eighteen months, the Financial Transaction Tax (or Robin Hood Tax) has shifted from a radical idea to a realistic proposition that has been considered by the IMF, the European Commission, the G20 and a number of national governments. This is an extraordinary turn around, in no small part due to the campaigning efforts of civil society organisations around the world. 2011 is the crunch point for the campaign and there is a window of opportunity to see significant progress on achieving the FTT. The French government hold the Chair of the G8 and G20 and are championing the FTT for global public goods, whilst public anger towards the financial sector grows as austerity measures begin to bite. Various options for taxing the financial sector are on the table and agreement by a first-wave group of countries during the first half of 2011 is critical. The key to timely progress will be leadership by the French government, and for France to enlist support from Germany and, hopefully, Britain. Renewed pressure from civil society, particularly on these key governments, will be essential to success. A coordinated Global Day of Action in February will kick-start the campaign in 2011 and demonstrate the global movement of citizens supporting a Robin Hood Tax. Objectives and Success Criteria 1. Influence key governments (French, German and UK) through their embassies a) The UK, German and French embassies* are lobbied in at least 15 countries around the world. b) The UK, German and French finance ministries receive communications from all lobbied embassies (via respective foreign offices) *If countries have capacity, they can lobby more than the top three targets.