Articulating Space Through Architectural Diagrams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glasgow School of Art Oration for Andy Bow Andy Bow Sir Norman

The Glasgow School of Art Oration for Andy Bow Andy Bow Sir Norman Foster once said, “As an architect you design for the present, with an awareness of the past and for a future which is essentially unknown.” Andy Bow is a senior partner in Foster and Partners, arguably the world’s most consistently innovative post war architectural practice. Since its inception in 1963, the practice has won an unprecedented number of international awards and competitions. Its output ranges from city masterplans to door handles; from yachts and bridges to light fittings. Few practices have embraced the uncertainties of the future so positively and with such confidence. Andy Bow has always displayed the key qualities of the very best Mac graduate; a sense of adventure and unbounded energy, a predisposition to collaboration, a passion for drawing, a generous spirit and the ability to remain close to both local roots and international horizons. These were all in evidence when, shortly after graduating and in collaboration with his long-standing friends and current Mac tutors Ian Alexander and Henry McKeown, they won the prestigious Manhattan Waterfront Competition. Chancellor, Andy Bow was born in 1961 in Edinburgh. He attended George Watson’s College, Telford College of Further Education and the Mackintosh School of Architecture at the Glasgow School of Art. Like myself, he chose to mix practice and education by joining the Mac’s part time course; a heady mixture of daytime office responsibilities and evening classes. When he eventually became a full time student, his studio design reviews quickly attracted attention. The potent mixture of his astonishing drawings and memorable exchanges with staff, particularly professors Andy McMillan and the late Isi Metzstein became must –see events for his fellow students. -

Early Sustainable Architecture in Hanging

Review articles • Oorsigartikels Christo Vosloo Prof. Christo Vosloo, Graduate School of Architecture, Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture, Published by the UFS University of Johannesburg, http://journals.ufs.ac.za/index.php/as P.O. Box 524, Auckland © Creative Commons With Attribution (CC-BY) Park, 2006, Johannesburg, How to cite: Vosloo, C. 2020. Early sustainable architecture South Africa. in hanging skyscrapers – A comparison of two financial office buildings. Acta Structilia, 27(1), pp. 144-177. Phone: +27 (0) 11 559 1105, E-mail: <[email protected]> ORCID: https://orcid. EARLY SUSTAINABLE org/0000-0002-2212-1968 ARCHITECTURE IN HANGING SKYSCRAPERS DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.18820/24150487/as27i1.6 – A COMPARISON OF TWO ISSN: 1023-0564 FINANCIAL OFFICE BUILDINGS e-ISSN: 2415-0487 Acta Structilia 2020 27(1): 144-177 Peer reviewed and revised March 2020 Published June 2020 *The authors declared no conflict of interest for the article or title ABSTRACT Reuse, or the ability to continue using an item or building beyond the initial function, is a key concept in the literature on sustainability. This implies that a building should be designed in a way that will allow it to be repurposed when changing circumstances require changes in its layout or function; being energy efficient and environmentally sensitive is not enough. The building also needs to be financially viable and the people whose lives are impacted by it should wish to have it retained. As far as flexibility of high-rise or skyscraper buildings is concerned, the structural system and layout are some, but not the only aspects that are of particular importance in this regard. -

The Work of Foster and Partners Specialist Modelling Group

The Work of Foster and Partners Specialist Modelling Group Brady Peters and Xavier DeKestellier Foster and Partners Architects and Designers Riverside Three 22 Hester Road London, UK SW11 4AN Abstract The following paper is a brief introduction to Foster and Partners and the work of its Specialist Modelling Group (SMG). The SMG was formed in 1997 and has been involved in over 100 projects. The SMG expertise encompasses architecture, art, math and geometry, environmental analysis, geography, programming and computation, urban planning, and rapid prototyping. The SMG brief is to carry out project-driven research and development. The group consults in the area of project workflow, advanced three-dimensional modelling techniques, and the creation of custom digital tools. The specialists in the team are a new breed of architectural designer, requiring an education based in design, math, geometry, computing, and analysis. 1. Foster and Partners Foster and Partners is an international studio for architecture, planning and design led by Norman Foster and a group of Senior Partners. Norman Foster's philosophy of integration can be seen in the way the practice's London design studio works; it is essentially one large open space, shared equally by everyone, and free of subdivisions to encourage good communication between the many people who come together there. The practice's work ranges in scale from the largest construction project on the planet, Beijing International airport to its smallest commission, a range of door furniture. The scope of its work includes masterplans for cities, the design of buildings, interior and product design, graphics and exhibitions. These can be found throughout the world, from Britain, Europe and Scandinavia to the United States, Hong Kong, Japan, China, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia and Australia. -

PHASE3 Architecture and Design

[email protected] 17 May 2017 BUILDINGS PLACES CITIES [email protected] 17 May 2017 LONDON: DESIGN CAPITAL BUILDINGS / PLACES / CITIES This NLA Insight Study was published by New London Architecture (NLA) in May 2017. It accompanies the NLA exhibition London: Design Capital on display from May–July 2017 and is part of the NLA International Dialogues year-round programme, supporting the exchange of ideas and information across key global markets. New London Architecture (NLA) The Building Centre 26 Store Street London WC1E 7BT Programme Champions www.newlondonarchitecture.org #LDNDesignCapital © New London Architecture (NLA) Programme Supporter ISBN 978-0-9956144-2-0 [email protected] 17 May 2017 2 Contents Forewords 4 Chapter one: London’s global position 6 Chapter two: London’s global solutions 18 Chapter three: London’s global challenges and opportunities 26 Chapter four: London’s global future 32 Project showcase 39 Practice directory 209 Programme champions and supporters 234 References and further reading 239 © Jason Hawkes – jasonhawkes.com [email protected] 17 May 2017 4 5 Creative Capital Global Business As a London based practice with offces based on three continents and London is the world’s global capital for creative design and construction a team of highly creative architects currently engaged in design and skills. Just as the City of London became the fnancial capital of the world, development opportunities around the globe, I welcome the NLA’s latest so London has beneftted from its history, its location, its legal and education insight study and exhibition London: Design Capital for two reasons. -

Proposed Evacuation Links at Height in the World Trade Center Design Entries

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Bridging the Gap: Proposed Evacuation Links at Height in the World Trade Center Design Entries Authors: Philip Oldfield, University of Nottingham Antony Wood, University of Nottingham Subjects: Architectural/Design Fire & Safety Keyword: Urban Design Publication Date: 2005 Original Publication: CTBUH 2005 7th World Congress, New York Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Philip Oldfield; Antony Wood Philip F. Oldfield School of the Built Environment, University of Nottingham Philip Oldfield is a postgraduate student of architecture at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. He has particular interest in the design of high-rise buildings, having previously participated in two tall building design research projects at Nottingham — the first on the Heron Tower project in London, the second on the concept of skybridges, entitled Pavements in the Sky. He has recently returned from a tall building study in Shanghai and is investigating the World Trade Center site and brief as a suitable vehicle for his final postgraduate design thesis. Mr. Oldfield has also been instrumental in the construction of the Web site for the Tall Buildings Teaching and Research Group, www.tallbuildingstarg.com. He currently works at the University of Nottingham as a research assistant. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Bridging the Gap: Proposed Evacuation Links at Height in the World Trade Center Design Entries This presentation is based on a paper by the presenter and Antony Wood of the University of Nottingham. The World Trade Center towers’ collapse has created the largest single retrospective analysis of tall building design in the past 40 years. -

Press Release Mclaren Technology Centre Shortlisted for 2005 Stirling Prize

Press release 27 July 2005 McLaren Technology Centre shortlisted for 2005 Stirling Prize Foster and Partners McLaren Technology Centre has been included on the six project shortlist of the coveted RIBA Stirling Prize, which is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year. The Royal Institute of British Architects presents the award annually to "the building which has made the greatest contribution to British Architecture in the past year." The McLaren Technology Centre is a showcase for technology and innovation. As well as providing the current technical team with the most sophisticated equipment to optimise its performance, the state-of-the-art facility also acts as an incentive to attract and retain the best engineering talent in the world, providing an impetus for the designers of the future. It is sensitively sited within the surrounding countryside and uses water from the dramatic lake and reed beds to naturally cool the building. The design was driven by a desire to create a sustainable and ecologically-friendly, flexible and pleasant working environment for a wide range of different functions. The McLaren Technology Centre centralises the majority of the McLaren Group's activities under one roof, in a facility that includes design studios, laboratories, research and testing capabilities, electronics development, machine shops and prototyping and production facilities for the company's Team McLaren Mercedes Formula 1 cars and the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren. Other projects included on the shortlist are Enric Miralles and RMJM's Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, Zaha Hadid's BMW Central Building in Leipzig, Bennetts Associates' Brighton Library, Alsop Design's Fawood Children's Centre and O'Donnell + Tuomey's Lewis Gluckman Gallery in Cork. -

Developer Brochure(WM)

vancouver’s urban weekly news • entertainment • life may 11-17, 2006 • free SELLING the DREAMAs the city grows, Vancouver’s real estate visionaries raise their game The Strokes’ Great eating and Burgess reflects on rock’n’roll odyssey waterfront views these Hedy times your city event listings Inside 05-11-06 ON THE COVER 13 There’s little doubt: Vancouver is Canada’s foremost real estate boomtown. Now, just as the city seems to have reached its peak, along comes Jameson House. A downtown high-rise development that respects both urban ecology and high-tech living, it’s also realty mogul Bob Rennie’s homage to the clout of its architects — London’s mighty Foster and Partners — and the rise of Vancouver to the international stage. Cover photo by Doug Shanks NEWS & VIEWS 5 The Column As a contender for the Liberal leadership, Hedy Fry’s got a public cross to bear by Steve Burgess 6 Life in Hell 6 Rant / Rave 7 News Granville Island’s managers respond to new competition by planning a revamp by Sean Condon 12 N e w s Turn that engine off: the city’s proposing a $100 fine for drivers of idling cars by Sean Condon A&E 14 Picks of the Week 7 Grand plans for 14 Stage At times hilarious, at times less so, Suspect: A Granville Island? Game of Murder is never dull by Steven Schelling 15 Music Even as the publicity machine slows, the Strokes are still managing to fill the arenas by Stuart Berman 16 Movies Reviewed this week: When Do We Eat?, On A Clear Day, Mission: Impossible III 17 Movie Times 18 Concerts & Events 23 Nightclub listings 25 Cat’s Eye -

30 St Mary Axe Callie Wendlandt | Brian Lopez | Ryan Lawrence | Garrett Barker | Jason Teal ARCH 631 | Prof

Source: Foster + Partners 30 St Mary Axe Callie Wendlandt | Brian Lopez | Ryan Lawrence | Garrett Barker | Jason Teal ARCH 631 | Prof. Nichols Project ● Location - London, United Kingdom ● Completed construction in 2003, opened in 2004 ● Client: Swiss Re Insurance Co. ● Architect: Foster and Partners ● Structural Engineer: ARUP ● Project Manager: RWG Associates ● Contractor: Skanska ● Building Services Engineer: Hilson Moran Partnership ● Cost Consultant: Gardiner & Theobold Source: Foster + Partners Project Background ● Previous building damaged in 1992 from IRA bombing ● Has won many awards that include: ○ London Architectural Biennale Best Building Award ○ LDSA Built in Quality Awards – Winner Innovation Category ○ Emporis Skyscraper Award 2003 ○ RIBA Stirling Prize ○ The International Highrise Award – Honourable Mention ○ Dutch Steel Award – Category A Source: Foster + Partners Site Analysis Urban Context ● 1.4 Acre Site in the Financial District ● Less than ½ mile to London Bridge ● ¾ mile to St. Paul’s Cathedral ● .2 miles to Underground Stop Source: Foster + Partners Consolidation of City Cluster of High Rise Buildings Source: Archdaily Source: Archdaily Source: Archdaily Wind + Temperature Annual Wind Pattern Temperature Range °F Source: Climate Consultant Max 25 mph Average Temp. 52 °F Seismic Hazards Intensity Range: 6.5 to 3.5 ● Large seismic events are rare ● The most powerful earthquake recorded in the UK occurred in the North Sea off the coast of Yorkshire in 1931. Magnitude 6.1 ● Last time people were killed due to seismic activity was in 1580; it damaged numerous buildings and caused two fatalities ● Areas of Seismic Hazard: ○ Highest: West of Scotland, North and South Wales ○ Lowest: Northern Ireland and Northeast Scotland ○ Southeast England has a low probability of experiencing a major seismic event. -

Glass Supper 2017 Outline

inside “The Tanks” at the New Tate Modern Thursday 7th December & The Society of Facade Engineering Awards People-centric Buildings designed with people in mind EVENT PARTNERS: The Glass Supper 2016 is presented by Intelligent Glass Solutions 2016 PEOPLE-CENTRIC BUILDINGS DESIGNED WITH PEOPLE IN MIND It’s glass because everybody likes to look outside… Over 300 guests from all over the world are committed to gathering face to face to join a one day experience that facilitates open, leadership level discussion, addressing high performing systems and solutions in today’s global architectural glass and facade industry. Coming together under the theme, People-centric, buildings designed with people in mind, the Glass Supper 2017 will help architects and glass industry decision makers keep humans at the centre of future structural building design, forming a template that will stimulate creativity and strengthen the architectural framework of life in the world to come. Glass Supper Speakers, an all star line up of award winning industry aces, will provide a series of arresting presentations in order to teach us the lessons we all need to learn. This remarkable one day event will focus on 3 essential areas: • Designing buildings and spaces that respond to today’s changing lifestyles and expectations • Visible yet invisible, the neutrality of glass and why it is such an essential structural material in terms of healing the environment and cultivating human creativity • Future-proofing buildings with glass, daylighting design and lasting improvements in the creation and design of the urban space. The Glass Supper 2017 is presented by Intelligent Glass Solutions BUILDINGS DESIGNED WITH PEOPLE IN MIND … Life is outside It is with great pleasure that we welcome Mr Ben Derbyshire as the Opening Speaker for the Glass Supper 2017, and indeed to congratulate Ben on his tenure as President of the RIBA (from September). -

Morgan Jenkins

MORGAN JENKINS _Contents _Projects _Projects [Cont] 01:Data Mont Duic - Unknown Deer Moat Tunnel - Josef Pleskot 02: Context Barcelona Pavilion - Mies an der Rohe Prague Castle Renovations - Jose Plecnik 03/04: Barcelona MACPA - Richard Meier Dancing House - Frank O. Gehry 05/06: London Mercat del Born - Unknown Unit Development - Safer Hajek Architekti 07/08: Prague Parc de la Ciutadella - Unknown Villa Rothmayer - Jose Plecnik /Otto Rothmayer 09: Postscript Barcelona Olympic Village Church of the Most Sacred Heart of Our Lord _People Parc Diagonal Mar - EMBT - Jose Plecnik Morgan Jenkins [Nielsen Jenkins] Forum - Herzog & de Meuron et al _Practices Louisa Gee [Partners Hill] Sagrada Familia - Antoni Gaudi Bofill taller de Arquitectura Clare Scorpo [Clare Scorpo Architects] Walden 7 - Bofill Arquitectura EMBT Imogene Tudor [Sam Crawford Architects] Bofill taller de Arquitectura - Bofill Arquitectura Office of Architecture Barcelona - OAB Carlos Ferrater Alberto Quinzon [CHROFI] Mercat de Santa Caterina - EMBT Studio Octopi Katelin Butler [Architecture Media] Estudio EMBT - EMBT Zaha Hadid Architects Mat Henson [Dulux] Gardunya Square - Estudio Carme Pinos AL_A - Amanda Levete Architects Phil White [Dulux] Office of Architecture Barcelona - OAB Wilkinson Eyre Jamie Penrose [AIA] Foster and Partners Jennifer Cunich [AIA] Silchester Estate - Haworth Tompkins ARCHIP Caitlin Buttress [AIA] Walmer Yard - Peter Salter Schindler Seko Architects Design Museum - John Pawson/RMJM/OMA FAM Architekti _Cities Tate Modern - Herzog & de Meuron Barcelona 19.05.2017 - 23.05.2017 20 Fenchurch St - Rafael Vinoli London 23.05.2017 - 27.05.2017 Lloyd’s of London - Richard Rogers Prague 27.05.2017 - 31.05.2017 122 Leadenhall - Rogers, Stirk, Harbour & Partners 30 St Mary Axe - Norman Foster Faraday House - dRMM Thames Pool - Studio Octopi City Passageways - Architect(s) Unknown DULUX STUDY TOUR_POST TOUR REPORT 01_DATA DATE : 19.05.2017 - 31.05.2017 MORGAN JENKINS First a project. -

Reference Buildings

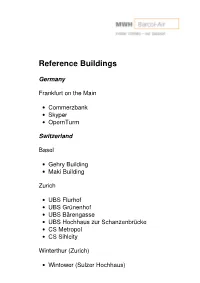

Reference Buildings Germany Frankfurt on the Main • Commerzbank • Skyper • OpernTurm Switzerland Basel • Gehry Building • Maki Building Zurich • UBS Flurhof • UBS Grünenhof • UBS Bärengasse • UBS Hochhaus zur Schanzenbrücke • CS Metropol • CS Sihlcity Winterthur (Zurich) • Wintower (Sulzer Hochhaus) Commerzbank Headquarter Frankfurt Over 40’000 sqm of General and Office Area, 15’000 sqm with active Radiant Cooled Ceilings. Plank Type Panels in the Open Plan Office Area The Architect Sir Norman Foster designed the 43- story building with staggered sections in a spiral between the three facades. The resulting garden atrium areas, these are 4 stories high, make the potentially dark centre of the building light and bright and give room for relaxation. The Commerzbank Tower is the tallest Building in Europe Garden Atrium Facts · Builder: HOCHTIEF AG, Frankfurt on the Main · Building structure: · Architect: Foster and Partners - 40‘000 sqm of general and office area · General contractor: Dr. Gubert - Height 259m Objekt, head office Frankfurt AG - 56 floors · Design engineer: Pettersson & Ahrens · Radiant ceiling system: Ingenieur-Planung GmbH,Frankfurt o. t. Main - Barcol-Air A11 Water Cooling System · Place: Kaiserplatz 1, 60261 Frankfurt o. t. Main · Opening: 1997 · Function: offices Reference Buildings / Marco L. Giavazzi 2 / 18 April 14., 2010 Commerzbank Headquarter Frankfurt As the heating and cooling of the building is achieved with a non air-only-system, as is the case in conventional buildings, the air exchange rate could be reduced to the minimal fresh air required without a proportion of recirculated air. This ensures high indoor air quality. In addition the high heat insulation quality of the façade and glazing together with the use of radiant cooling systems versus conventional air- conditioning systems, have ensured up to 30% energy savings! Since 1997 the Commerzbank has been a multi- Ceiling to Floor Windows results in bright Office Areas storey building workplace for over 2‘500 people. -

Sir Norman Foster

SIR NORMAN FOSTER Beijing Airport, China Source: http://www.fosterandpartners.com/ “the best architecture comes from a synthesis of all the elements that separately comprise a building…” -Foster Snow Show, Italy Source: http://www.fosterandpartners.com/ Commerzbank, Germany Center for Clinical Science Research, USA Hong Kong Bank Headquarters, Hong Kong British Museum, England Source: http://www.kvadrat.dk/ Source: http://www.gaborcselle.com/ Source: http://www.fosterandpartners.com/ Source: http://www.fosterandpartners.com/ images/Referencer/commerzbank.jpg sfbayarea4/images/06%20Stanford... • Born in 1935 in Manchester, England • Entered Manchester School of Architecture when 21 years old • Received Master’s Degree at Yale University Norman Foster • Norman, Wendy, Sue Rogers and Source: http://www.pritzkerprize.com/mediakit99.htm Richard Rogers form firm ‘Team 4’ in 1963 • Foster’s Associates (now known as Foster and Partners) created in 1967 • Receives AIA Gold Medal (1994) • Wins the Pritzker Architecture Prize (1999) • Currently has offices across the world in London, Berlin and Singapore with over 500 employees DESIGN PHILOSOPHY “Technology is part of civilization and being anti-technology would be like declaring war on architecture and civilization itself. If I can get carried away with some passion about the poetry of the light in one of my projects, then I can also, in the same vein, enjoy the poetry of the hydraulic engineering.” -Foster London City Hall (GLA) Hearst Tower Source: http://www.solvayindupa.com/static/wma/jpg/1/0/1/3/7/helicalramp.jpg