Lecture Delivered by Laurie Oakes at Curtin University on September 25,2014.

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Legal Document

Case 1:10-cv-00436-RMC Document 49-3 Filed 08/09/13 Page 1 of 48 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES ) UNION, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 1:1 0-cv-00436 RMC ) CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, ) ) Defendant. ) -----------------------J DECLARATION OF AMY E. POWELL I, Amy E. Powell, declare as follows: 1. I am a trial attorney at the United States Department of Justice, representing the Defendant in the above-captioned matter. I am competent to testify as to the matters set forth in this declaration. 2. Attached to this declaration as Exhibit A is a true and correct copy of a document entitled "Attorney General Eric Holder Speaks at Northwestern University School of Law," dated March 5, 2012, as retrieved on August 9, 2013 from http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/ag/speeches/ 2012/ag-speech-1203051.html. 3. Attached to this declaration as Exhibit B is a true and correct copy of a Transcript of Remarks by John 0. Brennan on April30, 2012, as copied on August 9, 2013 from http://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/the-efficacy-and-ethics-us-counterterrorism-strategy/ with some formatting changes by the undersigned in order to enhance readability. Case 1:10-cv-00436-RMC Document 49-3 Filed 08/09/13 Page 2 of 48 4. Attached to this declaration as Exhibit C is a true and correct copy of a letter to the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee dated May 22, 2013, as retrieved on August 9, 2013 from http://www.justice.gov/slideshow/AG-letter-5-22-13 .pdf. -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 2. Quartal 2009

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 2. Quartal 2009 Geschichte: Einführungen........................................................................................................................................2 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie ..........................................................................................................2 Teilbereiche der Geschichte (Politische Geschichte, Kultur-, Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte allgemein) ........4 Historische Hilfswissenschaften ..............................................................................................................................6 Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Mittelalter- und Neuzeitarchäologie.................................................................................8 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege......................................13 Alte Geschichte......................................................................................................................................................19 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit ...............................................................................................20 Deutsche Geschichte..............................................................................................................................................22 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte .....................................................................................................30 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs, -

Strategy-To-Win-An-Election-Lessons

WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 i The Institute of International Studies (IIS), Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is a research institution focused on the study on phenomenon in international relations, whether on theoretical or practical level. The study is based on the researches oriented to problem solving, with innovative and collaborative organization, by involving researcher resources with reliable capacity and tight society social network. As its commitments toward just, peace and civility values through actions, reflections and emancipations. In order to design a more specific and on target activity, The Institute developed four core research clusters on Globalization and Cities Development, Peace Building and Radical Violence, Humanitarian Action and Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. This institute also encourages a holistic study which is based on contempo- rary internationalSTRATEGY relations study scope TO and WIN approach. AN ELECTION: ii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 By Dafri Agussalim INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA iii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 Penulis: Dafri Agussalim Copyright© 2011, Dafri Agussalim Cover diolah dari: www.biogenidec.com dan http:www.foto.detik.com Diterbitkan oleh Institute of International Studies Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Gadjah Mada Cetakan I: 2011 x + 244 hlm; 14 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978-602-99702-7-2 Fisipol UGM Gedung Bulaksumur Sayap Utara Lt. 1 Jl. Sosio-Justisia, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281 Telp: 0274 563362 ext 115 Fax.0274 563362 ext.116 Website: http://www.iis-ugm.org E-mail: [email protected] iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revised version of my Master of Arts (MA) thesis, which was written between 1994-1995 in the Australian National University, Canberra Australia. -

Základní Atributy Značek ČSSD a ODS 2002-2013 Ve Volebních Kampaních

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sociálních studií Katedra politologie Mgr. Miloš Gregor Základní atributy značek ČSSD a ODS 2002–2013 ve volebních kampaních Disertační práce Školitel: doc. PhDr. Stanislav Balík, Ph.D. Brno 2016 !1 Čestné prohlášení Prohla"uji, #e jsem p$edkládanou diserta%ní práci Základní atributy značek ČSSD a ODS 2002– 2013 ve volebních kampaních vypracoval samostatn& a k jejímu vypracování pou#il jen t&ch pramen', které jsou uvedeny v seznamu literatury. (ást kapitoly 2.1 vychází z textu Klasické koncepty v politickém marketingu, kter) vy"el v knize Chytilek, R. et al. 2012. Teorie a metody politického marketingu, Brno: CDK. V kapitole 5.3.4 vycházím z kapitoly Předvolební kampaně 2013: prohloubení trendů, nebo nástup nových?, kterou jsem zpracoval spole%n& s Mgr. et Mgr. Alenou Mackovou. Tato kapitola byla publikována v rámci knihy Havlík, V. (Ed.) 2014. Volby do Poslanecké sněmovny 2013, Brno: Munipress. (ásti kapitol 3.9.1, 4.3 a 6.6 pak vychází z mého textu Where Have All the Pledges Gone: An Analysis of ČSSD and ODS Manifesto Promises since 2002, kter) vyjde v Politologickém %asopise v roce 2017. Texty byly pro pot$eby této práce jazykov& upraveny a zkráceny. P$evzaté texty tvo$í p$ibli#n& 5 % p$edlo#ené diserta%ní práce. V Brn&, dne 21. listopadu 2016 Milo" Gregor+ !2 Souhlas spoluautorky s použitím výsledků kolektivní práce Vyslovuji souhlas s tím, aby Milo" Gregor pou#il text Předvolební kampaně 2013: prohloubení trendů, nebo nástup nových?, kter) jsme vypracovali spole%n& a kter) byl publikován v rámci knihy Havlík, V. -

Melbourne Press Club Laurie Oakes Address 15 September 2017

MELBOURNE PRESS CLUB LAURIE OAKES ADDRESS 15 SEPTEMBER 2017 Thank you all for coming. And thank you to the Melbourne Press Club for organizing this lunch. Although I’m based in Canberra, I’ve long felt a strong link with this club and been involved in its activities when I can-- including a period as one of the Perkin Award judges. Many of the members are people I’ve worked with over the years. I feel I belong. So this farewell means a lot to me. When I picked up the papers this morning, my first thought was: “God, I’m so old I knew Lionel Murphy.” In fact, I broke the story of his terminal cancer that shut down the inquiry. But making me feel even older was the fact that I’d even had a bit to do with Abe Saffron, known to the headline writers as “Mr Sin”, in my brief period on police rounds at the Sydney Mirror. Not long after I joined the Mirror, knowing nothing and having to be trained from scratch, a young journo called Anna Torv was given the job of introducing me to court reporting. The case involved charges against Mr Saffron based on the flimsy grounds, I seem to recall, that rooms in Lodge 44, the Sydney motel he owned that was also his headquarters, contained stolen fridges. At one stage during the trial a cauliflower-eared thug leaned across me to hand a note to Anna. It was from Abe saying he’d like to meet her. I intercepted it, but I don’t think Anna would have had much trouble rejecting the invitation. -

Questions & Answers & Tweets

Questions & Answers & Tweets Jock Given & Natalia Radywyl Abstract This article reports on the integration of Twitter messages into the live television broadcast of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) weekly public affairs discussion program, Q&A. The program first went to air in May 2008; Twitter integration began two years later. Twitter integration is an evolving example of ‘participation television’, but not one that involves the kind of remote- control/set-top-box interactivity that digital television promised. Q&A integrates broadcast and online content in a way the program makers thought would serve the animating purpose of the television program: to increase public engagement in politics. It is an attempt to use the internet to make television better rather than to concede its eclipse, by marrying brief fragments of online speech with the one-way, single-channel authority of a television program broadcast live across a nation by a public service broadcaster. The research draws on data about Twitter use supplied by the ABC and its contractor TweeVee TV, OzTAM television ratings data, interviews and email correspondence with ABC staff and others conducted by the two authors between June and October 2011, and observations on the making of the episode of the show in Sydney on 29 May 2011. Keywords: digital television, public service broadcasting, social media, television, Twitter Here’s what we’ll be looking for as we dip into the #QandA stream— • tweets that are concise (short), timely and on topic • tweets that are witty and entertaining • tweets that add a fresh perspective to the debate • tweets that make a point without getting too personal (ABC 2011a) Introduction In May 2010, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) began to display Twitter ‘tweets’ on-screen in the broadcast of the hour-long, weekly current affairs discussion program, Q&A.1 In each hour-long episode, around 80–100 tweets using the hashtag #qanda are selected for display in the broadcast program. -

AAUW IOWA CONNECTOR March 2011 An

AAUW IOWA CONNECTOR March 2011 An Electronic Bulletin for AAUW Leaders in Iowa You are invited to share this information with other branch leaders and members by forwarding it to them or providing hard copy. Sandra Keist Wilson, President AAUW IA Happy St. Pats Day to all! April Showers bring State Conference! April 29-30 is the Annual Meeting and “Grow Your Branch, Grow Yourself” Conference Dates. Clarion Inn, Cedar Falls Gallagher Bluedorn Bldg. on UNI Campus The Initiative Newsletter will be in the mail the end of the week with all the particulars. Be sure to read it from beginning to end. If you can’t wait, an on-line copy along with the registration form is on the website, www.aauwiowa.org The conference program will give you hands-on experience, ideas on how to grow your branch and yourself using education, advocacy, and opportunity for community partners. Remember working together gets more done than alone. Come and be inspired for branch programing for 2011-12. Breaking through Barriers-Advocating for Change AAUW Convention 2011 Washington DC June 16-19 How exciting to be in DC. There are opportunities to attend a party at an embassy, visit the capital, participate in a service project, and an inspiring conference program. I hope many of you have an opportunity to attend. Some branches offer a conference scholarship to help cover some of the costs; members who attend return full of enriching experiences to share, ideas for programming, research to make use of, and issues for advocacy. Attendees grow within and show greater interest in leadership roles in their branch and state. -

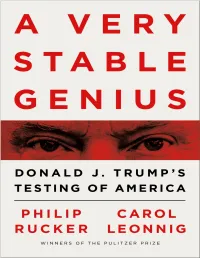

A Very Stable Genius at That!” Trump Invoked the “Stable Genius” Phrase at Least Four Additional Times

PENGUIN PRESS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2020 by Philip Rucker and Carol Leonnig Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952799 ISBN 9781984877499 (hardcover) ISBN 9781984877505 (ebook) Cover design by Darren Haggar Cover photograph: Pool / Getty Images btb_ppg_c0_r2 To John, Elise, and Molly—you are my everything. To Naomi and Clara Rucker CONTENTS Title Page Copyright Dedication Authors’ Note Prologue PART ONE One. BUILDING BLOCKS Two. PARANOIA AND PANDEMONIUM Three. THE ROAD TO OBSTRUCTION Four. A FATEFUL FIRING Five. THE G-MAN COMETH PART TWO Six. SUITING UP FOR BATTLE Seven. IMPEDING JUSTICE Eight. A COVER-UP Nine. SHOCKING THE CONSCIENCE Ten. UNHINGED Eleven. WINGING IT PART THREE Twelve. SPYGATE Thirteen. BREAKDOWN Fourteen. ONE-MAN FIRING SQUAD Fifteen. CONGRATULATING PUTIN Sixteen. A CHILLING RAID PART FOUR Seventeen. HAND GRENADE DIPLOMACY Eighteen. THE RESISTANCE WITHIN Nineteen. SCARE-A-THON Twenty. AN ORNERY DIPLOMAT Twenty-one. GUT OVER BRAINS PART FIVE Twenty-two. AXIS OF ENABLERS Twenty-three. LOYALTY AND TRUTH Twenty-four. THE REPORT Twenty-five. THE SHOW GOES ON EPILOGUE Acknowledgments Notes Index About the Authors AUTHORS’ NOTE eporting on Donald Trump’s presidency has been a dizzying R journey. Stories fly by every hour, every day. -

The Obama Administration and the Press Leak Investigations and Surveillance in Post-9/11 America

The Obama Administration and the Press Leak investigations and surveillance in post-9/11 America By Leonard Downie Jr. with reporting by Sara Rafsky A special report of the Committee to Protect Journalists Leak investigations and surveillance in post-9/11 America U.S. President Barack Obama came into office pledging open government, but he has fallen short of his promise. Journalists and transparency advocates say the White House curbs routine disclosure of information and deploys its own media to evade scrutiny by the press. Aggressive prosecution of leakers of classified information and broad electronic surveillance programs deter government sources from speaking to journalists. A CPJ special report by Leonard Downie Jr. with reporting by Sara Rafsky Barack Obama leaves a press conference in the East Room of the White House August 9. (AFP/Saul Loeb) Published October 10, 2013 WASHINGTON, D.C. In the Obama administration’s Washington, government officials are increasingly afraid to talk to the press. Those suspected of discussing with reporters anything that the government has classified as secret are subject to investigation, including lie-detector tests and scrutiny of their telephone and e-mail records. An “Insider Threat Program” being implemented in every government department requires all federal employees to help prevent unauthorized disclosures of information by monitoring the behavior of their colleagues. Six government employees, plus two contractors including Edward Snowden, have been subjects of felony criminal prosecutions since 2009 under the 1917 Espionage Act, accused of leaking classified information to the press— compared with a total of three such prosecutions in all previous U.S. -

Executive Order -- Blocking Property of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine | the White House

3/7/2014 Executive Order -- Blocking Property of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine | The White House Get Em a il Upda tes Con ta ct Us Home • Briefing Room • Presidential Actions • Executive Orders Search WhiteHouse.gov The White House Office of the Press Secretary For Immediate Release March 06, 2014 Executive Order -- Blocking Property of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine EXECUTIVE ORDER - - - - - - - BLOCKING PROPERTY OF CERTAIN PERSONS CONTRIBUTING TO THE SITUATION IN UKRAINE L A T E S T BL O G P O S T S By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, including the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.) (IEEPA), the National March 07, 2014 11:00 AM EST Emergencies Act (50 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.) (NEA), section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (8 Ask President Obama Your Health Care U.S.C. 1182(f)), and section 301 of title 3, United States Code, Questions on WebMD President Obama will sit down for his first-ever interview with WebMD, the leading source of I, BARACK OBAMA, President of the United States of America, find that the actions and policies of persons -- health information for consumers and health care including persons who have asserted governmental authority in the Crimean region without the authorization of professionals. Ask your question for President the Government of Ukraine -- that undermine democratic processes and institutions in Ukraine; threaten its Obama now. -

Spygate Exposed

SPYGATE EXPOSED The Failed Conspiracy Against President Trump Svetlana Lokhova DEDICATION I dedicate this book to the loyal men and women of the security services who work tirelessly to protect us from terrorism and other threats. Your constant vigilance allows us, your fellow citizens to live our lives in safety. And to every American citizen who, whether they know it or not—almost lost their birthright; government of the people, by the people, for the people—at the hands of a small group of men who sought to see such freedom perish from the earth. God Bless Us All. © Svetlana Lokhova No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the author. Svetlana Lokhova www.spygate-exposed.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: “Much Ado about Nothing” 11 Chapter Two: Meet the Spy 22 Chapter Three: Your Liberty under Threat 35 Chapter Four: Blowhard 42 Chapter Five: Dr. Ray S. Cline 50 Chapter Six: Foreign Affairs 65 Chapter Seven: The “Cambridge Club” 74 Chapter Eight: All’s Quiet 79 Chapter Nine: Motive 89 Chapter Ten: Means and Opportunity 96 Chapter Eleven: Follow the Money 116 Chapter Twelve: Treasonous Path 132 Chapter Thirteen: “Nothing Is Coincidence When It Comes to Halper” 145 Chapter Fourteen: Puzzles 162 Chapter Fifteen: Three Sheets to the Wind 185 Chapter Sixteen: Director Brennan 210 Chapter Seventeen: Poisonous Pens 224 Chapter Eighteen: Media Storm 245 Chapter Nineteen: President Trump Triumphant! 269 Conclusion: “I Am Not a Russian Spy” 283 What happened to the President of the United States was one of the greatest travesties in American history. -

Barack Obama's Twice-‐In-‐A-‐Lifetime Speech and Tony Abbott's

Barack Obama’s Twice-in-a-Lifetime Speech and Tony Abbott’s Unwelcome Welcome Brendan McCaffrie The visit of a United States President is among the more exciting events Australian parliamentarians experience. This was obvious on November 17, 2011 as they gathered eagerly waiting for President Barack Obama’s entry, and jostled to shake his hand afterwards. A similar sense of anticipation permeated the public galleries where I was one of several PhD students from ANU’s School of Politics and International Relations in attendance. Naturally, Obama’s visit prompted much media excitement and his address to parliament generated much analysis. This commentary focused on Obama’s message of US engagement in the Asia-Pacific region, and in particular what this means for China. However, it was not that Obama’s message was new, in fact it largely repeated President Bill Clinton’s 1996 address to Australia’s Parliament. The attention Obama’s message for China received was largely a result of a political context in which those same words seemed more provocative towards China. The media also highlighted Opposition Leader Tony Abbott’s defiance of convention in using his welcome speech to make partisan attacks against the government. Again, this was nothing new; Abbott had used his two previous welcomes to foreign leaders in the same way. The event gave followers of politics a rare opportunity to observe the performances of three distinct leaders in three distinct roles. These leadership roles impart varying levels of authority and encourage leaders to act in different ways. Of these, the role of the opposition leader in welcoming the visiting leader is most interesting because of its ambiguity.