Fire Blight of Apples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 170 7th International Conference on Energy and Environmental Protection (ICEEP 2018) Effects of water stress on the growth status of five species of shrubs Pingwei Xiang1,a, Xiaoli Ma1,b, Xuefeng Liu1,c, Xiangcheng Yuan1,d, Zhihua Fu2,e* 1Chongqing three gorges academy of agricultural sciences, Wanzhou, Chongqing, China 2Chongqing Three Gorges Vocational College, Wanzhou, Chongqing,China [email protected],[email protected],[email protected], [email protected],[email protected] *Corresponding author. Pingwei Xiang and Xiaoli Ma contributed equally to this work. Keywords: Water stress; shrubs; leaf relative water content; leaf water retention Abstract: A pot experiments were conducted to study the effects of water stress on plant Blade retention, leaf relative moisture content (LRWC), Morphology and growth status, five drought-resistant plants (Pyracantha angustifolia, Pyracantha fortuneana, Pyracantha fortuneana ‘Harlequin’, Ligustrum japonicum ‘Howardii’, Photinia glabra×Photinia serrulata ) were used as materials. The results showed that the drought resistant ability of five species of shrubs from strong to weak as follows: Ligustrum japonicum 'Howardii',Pyracantha fortuneana , Pyracantha angustifolia,Photinia glabra×Photinia serrulata,Pyracantha fortuneana 'Harlequin'. It was found with several Comprehensive indicators that the drought tolerance of Ligustrum japonicum 'Howardii' was significantly higher than that of the other four species, and its adaptability to water deficit was stronger, -

WRA Species Report

Family: Rosaceae Taxon: Pyracantha koidzumii Synonym: Cotoneaster koidzumii Hayata (basionym) Common Name Formosa firethorn tan wan huo ji Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: Chuck Chimera Designation: H(HPWRA) Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: Chuck Chimera WRA Score 7 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 y 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y 402 Allelopathic y=1, n=0 n 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 405 Toxic to animals y=1, -

Horticulture 2015 Newsletter No

Horticulture 2015 Newsletter No. 9 March 3, 2015 2021 Throckmorton Plant Science Cntr. Manhattan, KS 66506 (785) 532-6173 Video of the Week: Growing Asparagus VEGETABLES Bolting and Buttoning in Cole Crop Plants Broccoli, cabbage and cauliflower are cole crops that have a tendency to bolt (go to seed) or button (produce an extremely small head) if plants are not grown properly. These crops need to be kept actively growing through their production cycle, including growing transplants from seed. If they slow down due to under-fertilization or are stunted due to overgrowing their container, buttoning or bolting is more likely. If you are not growing your own transplants but rather selecting plants from a retailer, choose small, stocky dark green plants. Even after transplanting, these plants need to be well-fertilized. Fertilize at transplanting with a starter solution and continue to fertilize every 2 to 3 weeks until harvest. Both buttoning and bolting are irreversible. Once a seed stalk starts for form, nothing can be done to force the plant to produce a normal crop. (Ward Upham) FRUIT Strawberry Mulch Removal Research done in Illinois has shown that the straw mulch should be removed from strawberry plants when the soil temperature is about 40 degrees F. Fruit production drops if the mulch remains as the soil temperature increases. There are likely to be freezing temperatures that will injure or kill blossoms, so keep the mulch between rows to conveniently recover the berries when freezing temperatures are predicted. (Ward Upham) FLOWERS Fertilizing Perennial Flowers Most flowering perennials are not heavy feeders, and once established, may not need fertilizing every year. -

Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains

United States Department of Agriculture Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Service Research Station Report RMRS-GTR-335 November 2016 Bergdahl, Aaron D.; Hill, Alison, tech. coords. 2016. Diseases of trees in the Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-335. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 229 p. Abstract Hosts, distribution, symptoms and signs, disease cycle, and management strategies are described for 84 hardwood and 32 conifer diseases in 56 chapters. Color illustrations are provided to aid in accurate diagnosis. A glossary of technical terms and indexes to hosts and pathogens also are included. Keywords: Tree diseases, forest pathology, Great Plains, forest and tree health, windbreaks. Cover photos by: James A. Walla (top left), Laurie J. Stepanek (top right), David Leatherman (middle left), Aaron D. Bergdahl (middle right), James T. Blodgett (bottom left) and Laurie J. Stepanek (bottom right). To learn more about RMRS publications or search our online titles: www.fs.fed.us/rm/publications www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/ Background This technical report provides a guide to assist arborists, landowners, woody plant pest management specialists, foresters, and plant pathologists in the diagnosis and control of tree diseases encountered in the Great Plains. It contains 56 chapters on tree diseases prepared by 27 authors, and emphasizes disease situations as observed in the 10 states of the Great Plains: Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming. The need for an updated tree disease guide for the Great Plains has been recog- nized for some time and an account of the history of this publication is provided here. -

Managing Fire Blight by Choosing Decreased Host Susceptibility Levels and Rootstock Traits , 2020 , January 15 January

Managing Fire Blight by Choosing Decreased Host Susceptibility Levels and Rootstock Traits , 2020 , January 15 January Awais Khan Plant Pathology and Plant-microbe Biology, SIPS, Cornell University, Geneva, NY F ire blight bacterial infection of apple cells Khan et al. 2013 Host resistance and fire blight management in apple orchards Host resistance is considered most sustainable option for disease management due to Easy to deploy/implement in the orchards Low input and cost-effective Environment friendly No choice to the growers--most of the new and old cultivars are highly susceptible Apple breeding to develop resistant cultivars Domestication history of the cultivated apple 45-50 Malus species-----Malus sieversii—Gene flow Malus baccata Diameter: 1 cm Malus sieversii Malus baccata Diameter: up to 8 cm Malus orientalis Diameter: 2-4 cm Malus sylvestris Diameter: 1-3 cm Duan et al. 2017 Known sources of major/moderate resistance to fire blight to breed resistant cultivars Source Resistance level Malus Robusta 5 80% Malus Fusca 66% Malus Arnoldiana, Evereste, Malus floribunda 821 35-55% Fiesta, Enterprise 34-46% • Fruit quality is the main driver for success of an apple cultivar • Due to long juvenility of apples, it can take 20-25 years to breed resistance from wild crab apples Genetic disease resistance in world’s largest collection of apples Evaluation of fire blight resistance of accessions from US national apple collection o Grafted 5 replications: acquired bud-wood and rootstocks o Inoculated with Ea273 Erwinia amylovora strain -

Passion Fruit Passiflora Edulis Firethorn Pyracantha Angustifolia

Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC) Hawaii‘i Island Weed ID Card – DRAFT– v20030508 Local Name: Passion Fruit Scientific Name: Passiflora edulis Family : ( Family) Origin and Status: ?Invasive weed in Hawai‘i ?Native to ?First introduced to into Hawai‘i in Description: Distribution: Other Information: Contact: Passion Fruit Passiflora edulis Prepared by MLC Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC) Local Name: Firethorn Hawaii‘i Island Weed ID Card – DRAFT– v20030508 Scientific Name: Pyracantha angustifolia Family : Rosaceae (Rose Family) Origin and Status: ?Invasive weed in Hawai‘i ?Native to southwestern China ?First naturalized collection taken from Kauai‘i in 1986 Description: Pyracantha angustifolia is a thick shrub that can grow up to 13 feet tall. It has small (¾-2” long, ½” wide), dark green oblong-shaped leaves with rounded tips. The leaf undersides may be a green-gray color because of dense short hairs. Its stems are woody and sparsely covered with long hard thorns. Small white flowers (up to ¾” wide) have from 4 to 10 petals and are arranged in clumps along the stems. The fruits are red to orange in color and are less than ½” wide. Distribution: P. angustifolia has been found from Mountain View through the Volcano Golf Course in mesic forest, along disturbed roadsides and abandoned agricultural lands. It is also established on Kaua‘i. It is probably spread by birds and rats. Other Information: The firethorn bush is used as an ornamental in many places in the world, including Hawai‘i. In Hawai‘i, firethorn escapes cultivation and forms dense thickets. The thickets easily overgrow native plants, and prevent new plants from sprouting. -

Tree Diseases

Tree Diseases In North Texas home owners cherish their trees for their beauty and for their shade protection from summer’s sun. Unfortunately, trees can experience problems that affect their attractive appearance and may even lead to death. Trees are vulnerable to environmental stress, infectious diseases, insects and human-caused damage. Correctly diagnosing the cause of a tree’s problem is the most important step in successful treatment. To determine if your tree has a disease, examine the whole tree not just the area showing symptoms suggests Iowa State University Extension Service (Diagnosing Tree Problems). Check leaves for holes or ragged edges, discoloration or deformities Look at the tree’s trunk for damage to the bark such as cracks or splits Consider previous activity that may have impacted the tree’s root system such as planting shrubs nearby or construction of a sidewalk or adding hardscape like a deck or patio The following diseases occur in Denton County. This is not all-inclusive, but Master Gardeners have seen all of these (with the exception of oak wilt). If you need help diagnosing a tree problem, send a picture of the entire tree and close-ups of the problem area(s) to the help desk at [email protected]. If it is a new tree, include a picture of the bottom of the trunk where it meets the soil. Include such information as: Age of the tree When the problem was noticed Sudden or gradual onset Presence of insects Anything else you believe is relevant Anthracnose This fungus is usually on lower branches, following a cool, wet, spring. -

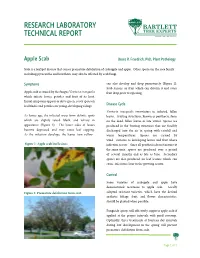

Apple Scab Bruce R

RESEARCH LABORATORY TECHNICAL REPORT Apple Scab Bruce R. Fraedrich, PhD, Plant Pathology Scab is a leafspot disease that causes premature defoliation of crabapple and apple. Other species in the rose family including pyracantha and hawthorn may also be affected by scab fungi. Symptoms can also develop and drop prematurely (Figure 2). Scab lesions on fruit which can deform it and cause Apple scab is caused by the fungus Venturia inaequalis fruit drop prior to ripening. which infects leaves, petioles and fruit of its host. Initial symptoms appear as olive-green, sooty spots on Disease Cycle leaf blades and petioles on young, developing foliage. Venturia inaequalis overwinters in infected, fallen As leaves age, the infected areas form definite spots leaves. Fruiting structures, known as perithecia, form which are slightly raised, black, and velvety in on the dead, fallen leaves in late winter. Spores are appearance (Figure 1). The lower sides of leaves produced in the fruiting structures that are forcibly become depressed and may cause leaf cupping. discharged into the air in spring with rainfall and As the infection develops, the leaves turn yellow warm temperatures. Spores are carried by wind currents to developing leaves and fruit where Figure 1: Apple scab leaf lesions infection occurs. Since all perithecia do not mature at the same time, spores are produced over a period of several months and as late as June. Secondary spores are also produced on leaf lesions which can cause infections later in the growing season. Control Some varieties of crabapple and apple have demonstrated resistance to apple scab. Locally Figure 2: Premature defoliation from scab adopted resistant varieties, which have the desired aesthetic foliage, fruit, and flower characteristics, should be planted when possible. -

Fire Blight of Apple and Pear

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Fire Blight of Apple and Pear Updated by Tianna DuPont, WSU Extension, February 2019. Original publication by Tim Smith, Washington State University Tree Fruit Extension Specialist Emeritus; David Granatstein, Washington State University; Ken Johnson, Professor of Plant Pathology Oregon State University. Overview Fire blight is an important disease affecting pear and apple. Infections commonly occur during bloom or on late blooms during the three weeks following petal fall. Increased acreage of highly susceptible apple varieties on highly susceptible rootstocks has increased the danger that infected blocks will suffer significant damage. In Washington there have been minor outbreaks annually since 1991 and serious damage in about 5-10 percent of orchards in 1993, 1997, 1998, 2005, Figure 2 Bloom symptoms 12 days after infection. Photo T. DuPont, WSU. 2009, 2012, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018. Shoot symptoms. Tips of shoots may wilt rapidly to form a Casual Organism “shepherd’s crook.” Leaves on diseased shoots often show blackening along the midrib and veins before becoming fully Fire blight is caused by Erwinia amylovora, a gram-negative, necrotic, and cling firmly to the host after death (a key rod-shaped bacterium. The bacterium grows by splitting its diagnostic feature.) Numerous diseased shoots give a tree a cells and this rate of division is regulated by temperature. Cell burnt, blighted appearance, hence the disease name. division is minimal below 50 F, and relatively slow at air temperatures between 50 to 70 F. At air temperatures above 70 F, the rate of cell division increases rapidly and is fastest at 80 F. -

Cherry Fire Blight

ALABAMA A&M AND AUBURN UNIVERSITIES Fire Blight on Fruit Trees and Woody Ornamentals ANR-542 ire blight, caused by the bac- Fterium Erwinia amylovora, is a common and destructive dis- ease of pear, apple, quince, hawthorn, firethorn, cotoneaster, and mountain ash. Many other members of the rose plant family as well as several stone fruits are also susceptible to this disease (Table 1). The host range of the Spur blight on crabapple fire blight pathogen includes cv ‘Mary Potter’. nearly 130 plant species in 40 genera. Badly diseased trees and symptoms are often referred to shrubs are usually disfigured and as blossom blight. The blossom may even be killed by fire blight phase of fire blight affects blight. different host plants to different degrees. Fruit may be infected Symptoms by the bacterium directly through the skin or through the The term fire blight describes stem. Immature fruit are initially Severe fire blight on crabapple the blackened, burned appear- water-soaked, turning brownish- cv ‘Red Jade’. ance of damaged flowers, twigs, black and becoming mummified and foliage. Symptoms appear in as the disease progresses. These Shortly after the blossoms early spring. Blossoms first be- mummies often cling to the trees die, leaves on the same spur or come water-soaked, then wilt, for several months. shoot turn brown on apple and and finally turn brown. These most other hosts or black on Table 1. Plant Genera That Include Fire Blight Susceptible Cultivars. Common Name Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Apple, Crabapple Malus Jetbead Rhodotypos -

Fireblight–An Emerging Problem for Blackberry Growers in the Mid-South

North American Bramble Growers Research Foundation 2016 Report Fire Blight: An Emerging Problem for Blackberry Growers in the Mid-South Principal Investigator: Burt Bluhm University of Arkansas Department of Plant Pathology 206 Rosen Center Voice: (479) 575-2677 Fax: (479) 575-7601 Julia Stover University of Arkansas Department of Plant Pathology 211 Rosen Center A poster with many of these initial findings was presented at the North American Berry Conference in Grand Rapids, MI in December 2016 Background and Initial Rationale: Fire blight, caused by the bacterial pathogen Erwinia amylovora, infects all members of the family Rosaceae and is considered to be the single most devastating bacterial disease of apple. Erwinia amylovora was first isolated from blighted blackberry plants in Illinois in 1976, from both mummified fruit and blighted canes (Ries and Otterbacher, 1977). These symptoms had been sporadically reported previously in both blackberry and raspberry, but the causal agent had never been identified. Since this first report, the disease has been found throughout the blackberry growing regions of the United States, but is generally not considered to be a pathogen of major concern (Smith, 2014; Clark, personal communication). However, with the advent of primocane fruiting plants, a significant increase in disease incidence has been witnessed in Arkansas (Garcia, personal communication) and fruit loss of up to 65% has been reported in Illinois (Schilder, 2007). Fire blight is a disease that is very environmentally dependent, and warm, wet weather at flowering is most conducive to serious disease development. The Arkansas growing conditions are ideal for disease development, and the shift in production season with primocane fruiting moves flowering time to a time of year with temperatures cool enough for bacterial growth (Smith, 2014). -

Home Orchards Disease and Insect Control Recommendations

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT Home Orchards Disease and Insect Control Recommendations Apple and Pear Apple and pear trees are subject to serious damage from pests. As a result, a preventive spray program is needed. The following practices will improve the effectiveness of the pesticides and may lessen the need for sprays. ■ Plant disease-resistant varieties. This method of disease control is especially important for fire blight, where chemical control options are limited. Varieties resistant to cedar-apple rust, scab, and powdery mildew also are available and will potentially reduce the need for sprays. ■ Rake and destroy leaves in the fall if apple scab or pear leaf spot are problems. The fungi that cause these diseases can survive through the winter in ■ Prune out and destroy all dead or diseased shoots infected leaves. and limbs during the dormant season. This helps to reduce fire blight, fruit rots, and certain leaf spots, ■ Remove diseased galls from cedar trees. Spores as the organisms that cause these diseases can from these cedars can infect apples, causing cedar- survive through the winter in the wood. Removing apple rust. Elimination of the source of spores (cedar mummified (dark, shriveled, dry) fruit helps to prevent trees) is effective but not always possible. Where the overwintering of the fruit rot organisms. cedars are part of an established landscape, remove and destroy all galls caused by the rust fungus on ■ Prune out fire blight–affected shoots and blossom cedars in the late fall. Inspect the cedars again in clusters during the growing season only as symptoms the early spring during or just after a rain when the appear.