(Megaceryle Torquata Stictipennis) in Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Documented Observation of Ringed Kingfisher in Arizona by Jeff Coker, Vail, Az 85641 ([email protected])

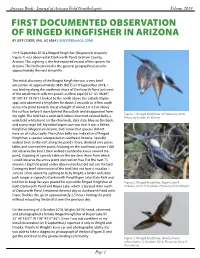

Arizona Birds - Journal of Arizona Field Ornithologists Volume 2019 FIRST DOCUMENTED OBSERVATION OF RINGED KINGFISHER IN ARIZONA BY JEFF COKER, VAIL, AZ 85641 ([email protected]) On 9 September 2018 a Ringed Kingfisher (Megaceryle torquata, Figure 1) was observed at Dankworth Pond, Graham County, Arizona. This sighting is the first reported record of this species for Arizona. The bird remained in the general geographical area for approximately the next 6 months. The initial discovery of the Ringed Kingfisher was a very brief encounter. At approximately 0845 (MST) on 9 September 2018, I was birding along the southeast shore of Dankworth Pond just west of the small marsh with the pond’s outflow pipe (N 32° 43’ 08.89”, W 109° 42’ 14.76”). I looked to the north above the cattails (Typha spp.) and observed a kingfisher for about 2 seconds as it flew south across the pond towards me at a height of about 3.0-4.5 m above the surface before it dove behind the cattails and disappeared from Figure 1. Ringed Kingfisher 20 February 2019. my sight. The bird had a solid dark rufous/chestnut colored belly, a Photo by Lyndie M. Warner wide bold white band on the chin/neck, dark slate blue on the back, and a very large bill. My initial impression was that it was a Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon), but I knew that species did not have an all-rufous belly. The rufous belly was indicative of Ringed Kingfisher, a species unexpected in southeast Arizona. I quickly walked back to the east along the pond’s shore, climbed on a picnic table, and scanned the pond, focusing on the southeast corner. -

Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0

NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA 115 Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0 October 1997 Seattle, Washington noaa NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION National Ocean Service Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce The Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) provides decisionmakers comprehensive, scientific information on characteristics of the oceans, coastal areas, and estuaries of the United States of America. The information ranges from strategic, national assessments of coastal and estuarine environmental quality to real-time information for navigation or hazardous materials spill response. Through its National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program, ORCA uses uniform techniques to monitor toxic chemical contamination of bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters, and sediments at about 300 locations throughout the United States. A related NS&T Program of directed research examines the relationships between contaminant exposure and indicators of biological responses in fish and shellfish. Through the Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (HAZMAT) Scientific Support Coordination program, ORCA provides critical scientific support for planning and responding to spills of oil or hazardous materials into coastal environments. Technical guidance includes spill trajectory predictions, chemical hazard analyses, and assessments of the sensitivity of marine and estuarine environments to spills. To fulfill the responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce as a trustee for living marine resources, HAZMAT’s Coastal Resource Coordination program provides technical support to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during all phases of the remedial process to protect the environment and restore natural resources at hundreds of waste sites each year. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Breeding Biology of Blue-Eared Kingfisher Alcedo Meninting Sachin Balkrishna Palkar

PALKAR: Blue-eared Kingfisher 85 Breeding biology of Blue-eared Kingfisher Alcedo meninting Sachin Balkrishna Palkar Palkar, S. B., 2016. Breeding biology of Blue-eared Kingfisher Alcedo meninting. Indian BIRDS 11 (4): 85–90. Sachin Balkrishna Palkar, Near D. B. J. College Gymkhana, Sathyabhama Sadan, House No. 100, Mumbai–Goa highway, Chiplun 415605, Ratnagiri District, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received on 30 November 2015. Abstract The breeding biology of the Blue-eared Kingfisher Alcedo meninting was studied in Ratnagiri District, Maharashtra, India, between 2012 and 2015. Thirteen clutches of four pairs were studied. Its breeding season extended from June till September. Pairs excavated tunnels ranging in lengths from 18 to 30 cm, with nest entrance diameters varying from 5.3 to 6.0 cm. The same pair probably reuse a nest across years. A typical clutch comprised six eggs. The incubation period was 21 days (20–23 days), while fledgling period was 23 days (20–27 days). Almost 40% of the nests were double-brooded, which ratio probably depends on the strength of the monsoon. Of 75 eggs laid, 66 hatched (88%), of which 60 fledged (90.9%; a remarkable breeding success of 80%. Introduction and not phillipsi. It is also found in the Andaman Islands (A. The Blue-eared KingfisherAlcedo meninting [113, 114] is m. rufiagastra), where it is, apparently, more abundant than morphologically similar to the Common KingfisherA. atthis but the Common Kingfisher, contrary to its status elsewhere in its is neither as common, nor as widely distributed, in India, as the range (Rasmussen & Anderton 2012). -

Three New Species of Birds Identified on Bonaire

Three New Species of Birds Identified on Bonaire by Peter Paul Schets Brown-chested martin. Photo © Steve by: Schnoll 2019 proved to be an exciting year for birders Brown-chested martin (Progne tapera) on Bonaire, as three new species have been On June 7th 2019 Peter-Paul Schets noticed two identified. The Brown-chested martin, White- large martins which flew in very fast, wide circles collared swift and Ringed kingfisher were added in Lac Cai. These birds flew for hundreds of meters to Bonaire’s increasing index of local birds. very low, near the ground, a behavior which he had Documenting and understanding local bird popu- not seen before in Caribbean martins (a species lations is crucial in developing management and not uncommon on Sint Eustatius and Saba). Due protection plans for Bonaire’s natural resources. to the brown coloration of the bird’s backs Schets believed he had found Brown-chested martins. As The number of bird species recorded on Bonaire the light was already poor, Schets was not able to is growing each year. In 2016, three new species take any decent photos. He sent resident birder and were identified, the Lesser black-backed gull, Pied photographer Steve Schnoll a message and asked water-tyrant and Dickcissel. Additionally, six new him if could visit the location during the following species were identified in 2017, Oilbird, Greater ani, day to photograph the birds. The next morning, Smooth-billed ani, Prairie warbler, Black vulture Schnoll quickly found the two birds and was able to and Cory’s shearwater. In 2018, an unexpected take several great photos. -

Check List 4(2): 152–158, 2008

Check List 4(2): 152–158, 2008. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Mammals, Birds and Reptiles in Balbina reservoir, state of Amazonas, Brazil. Márcia Munick Mendes Cabral Gália Ely de Mattos Fernando César Weber Rosas Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA). Laboratório de Mamíferos Aquáticos. Caixa Postal 478. CEP 69011-970, Manaus, AM, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The construction of hydroelectric power stations can affect the fauna, including the adaptation to the new lentic conditions, and may lead to the disappearance of some species and the colonization of others. Usually, there is a lack of information in the post-flooding phases. The present study is a preliminary qualitative survey of mammals, birds, and reptiles in the influenced area of the Balbina hydroelectric dam (01º55' S, 59º29' W). Species records were made during field trips to the reservoir with no group specific methods. The conservation status of the identified species followed the classification adopted by IUCN. Twenty-two mammals (one endangered – EN), forty-two birds and six reptiles (one vulnerable – VU) were identified. Although the list presented here is preliminary, if appropriately complemented it can be used to understand the effects of hydroelectric dams on the Amazonian fauna. Introduction The construction of large hydroelectric power et al. 2007) by the researchers of the Laboratório stations can affect the fauna by large impacts on de Mamíferos Aquáticos of the Instituto Nacional the aquatic and terrestrial environments. Wild de Pesquisas da Amazônia (LMA/INPA). Due to animals are intimately related with their the lack of information about the fauna that surroundings and can be strongly affected by currently inhabits the Balbina reservoir, and drastic alterations in the habitats. -

Starter Deck Version 2.0 Phylo: the Trading Card Game

STARTER DECK VERSION 2.0 PHYLO: THE TRADING CARD GAME THIS DOCUMENT INCLUDES 17 PAGES OF CARDS (100 PHYLO CARDS). NOTE THAT CARD SIZE IS IDENTICAL TO THAT OF POKEMON CARDS (62 mm x 87 mm or 2 7/16 inches x 3 7/16 inches). WE RECOMMEND PRINTING THESE CARDS, IN COLOUR, ON 65LB+ WHITE CARD STOCK. USING CARD SLEEVE PROTECTORS (~64mm x 89mm) WILL ALSO GREATLY ENHANCE THE FEEL OF THE CARDS. WE ARE CURRENTLY FINALIZING THE “CARD BACK” DESIGN, WHICH SHOULD BE READY FOR DOWNLOADING AND PRINTING IN EARLY 2012. FOR MORE CARDS, GAME RULES, AND GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE PHYLO PROJECT, PLEASE GO TO: http://phylogame.org Marine Debris Linnaeus Card Horned Puffin Event Card Event Card Fratercula corniculata Event Event Animalia,Chordata,Aves PLAY: on 1 SPECIES card with Ocean or Fresh PLAY: can be played immediately for below effect and then 7 POINTS Water TERRAIN. discarded. • Fratercula corniculata has a FLIGHT of 2. EFFECT: The played SPECIES card is discarded. EFFECT: When used, if a player can remember the latin name for an organism in his/her discard pile, then he/she • Fratercula corniculata nest in bluffs of fractured rock or can retrieve that card. crevices in cliff faces near the shoreline. Image by Alexandria Neonakis Image by Alexander Roslin Image by latyshoffa alexneonakis.com/ en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus latyshoffa.deviantart.com/ Cold, Cool Pool Frog American Robin Common Fruit Fly Pelophylax lessonae Turdus migratorius Drosophila melanogaster Animalia,Chordata,Amphibia Animalia,Chordata,Aves Animalia,Arthropoda,Insecta 6 POINTS 3 POINTS 4 POINTS • Pelophylax Lessonae has a MOVE of 2. -

Ringed Kingfisher at Austin, Texas.-On November 15, 1955, Eugene S

THE WILSON BULLETIN Decmnber 1956 Vol. 68, No. 4 the incubation of the eggs. On that occasion, I heard a tattler call two or three times near me and saw it on the margin of a gravel apron. Soon it moved slowly, with many stops, out on the gravel, and when it had reached about the middle of the gravel area a second tattler stood up beside it, and shortly flew away. It had been sitting on a clutch of eggs. The first tattler at once settled on the nest. A further sharing of family responsibilities was observed after the eggs hatched. On the morning of June 29, a cool and cloudy day, I saw one of the parents brooding the young in the nest. The eggs had hatched sometime after I checked the nest on the preceding day. I left the parent undisturbed, and in half an hour returned with a camera. During my absence the family had left the nest, and the young were being brooded on the gravel about 30 yards from it. In a few minutes the tiny chicks scampered forth, and on twinkling feet scattered over the bar, 20 or 30 yards, in various directions in their active search for food. While the young foraged, the parent called at intervals, the calls serving perhaps to circumscribe the wanderings of the babies. The chicks called too, but so faintly and softly that the calls were hardly audible. In about five minutes the parents’ calls became a little louder. It was evident that it was summoning the chicks. -

Spring 2018 Dear Adults Puzzles and Activities

Spring 2018 Spring Across 2. The way water moves through an ecosystem (Water Cycle) Coloring and Games.………...10-11 and Coloring 4. A small narrow river (Stream) Spotlight on Kingfishers…….....8-9 on Spotlight 8. Tall "hot dog" plants (Cattails) 10. Tall wading bird (Great Blue Heron) 6-7 I Spy…………….. I 13. Fish that migrate from the river to ocean and back (Salmon) …………………..…... 14. Insect that can fly backwards (Dragonfly) Food Webs……………………….……4-5 Food 15. Seattle Audubon's logo bird (Cormorant) 16. A small body of fresh water (Pond) Let’s Go Outside................................3 Go Let’s Down 1. Bird with red wing patch on the shoulder (Red Winged Blackbird) Dear Adults……………………..….........2 Dear 3. Two things that tired, hungry migrating birds get from wetlands (Food and Rest) Inside 5. Falling water from the sky (Rain) 6. Duck with green head (Mallard) Seattle Times Photo Contest Photo Times Seattle 7. Flying south for the winter (Migration) Photo credit: Jerry Ackerson, Seattle Audubon – Audubon Seattle Ackerson, Jerry credit: Photo 9. Water in the sky (Clouds) 11. How water turns from liquid to gas (Evaporation) 12. This month's cover bird (Belted Kingfisher) Answers from kingfisher page: 1) True, 2) True, 3) False, some kingfishers don’t eat any fish at all!, 4) True, 5) False, They come in all different colors and sizes! A-4, B-2, C-1, D-3 and not feed them at all! at them feed not and simply enjoy their presence presence their enjoy simply Or better yet, you could also also could you yet, better Or seed, or frozen peas or corn. -

Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 1 Josh Engel

Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 1 Josh Engel Photos: Josh Engel, [[email protected]] Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History and Tropical Birding Tours [www.tropicalbirding.com] Produced by: Tyana Wachter, R. Foster and J. Philipp, with the support of Connie Keller and the Mellon Foundation. © Science and Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [[email protected]] [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org/guides] Rapid Color Guide #584 version 1 01/2015 1 Struthio camelus 2 Pelecanus onocrotalus 3 Phalacocorax capensis 4 Microcarbo coronatus STRUTHIONIDAE PELECANIDAE PHALACROCORACIDAE PHALACROCORACIDAE Ostrich Great white pelican Cape cormorant Crowned cormorant 5 Anhinga rufa 6 Ardea cinerea 7 Ardea goliath 8 Ardea pupurea ANIHINGIDAE ARDEIDAE ARDEIDAE ARDEIDAE African darter Grey heron Goliath heron Purple heron 9 Butorides striata 10 Scopus umbretta 11 Mycteria ibis 12 Leptoptilos crumentiferus ARDEIDAE SCOPIDAE CICONIIDAE CICONIIDAE Striated heron Hamerkop (nest) Yellow-billed stork Marabou stork 13 Bostrychia hagedash 14 Phoenicopterus roseus & P. minor 15 Phoenicopterus minor 16 Aviceda cuculoides THRESKIORNITHIDAE PHOENICOPTERIDAE PHOENICOPTERIDAE ACCIPITRIDAE Hadada ibis Greater and Lesser Flamingos Lesser Flamingo African cuckoo hawk Common Birds of Namibia and Botswana 2 Josh Engel Photos: Josh Engel, [[email protected]] Integrative Research Center, Field Museum of Natural History and Tropical Birding Tours [www.tropicalbirding.com] Produced by: Tyana Wachter, R. Foster and J. Philipp, -

Ceryle Rudis)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/409201; this version posted September 7, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Sustained hovering, head stabilization and vision through the water surface in the Pied 2 kingfisher (Ceryle rudis) 3 4 Gadi Katzir*, Department of Evolutionary and Environmental Biology, Faculty of Life Sciences, 5 University of Haifa, Mt Carmel, Haifa 3498838, Israel. Email: [email protected] 6 7 Dotan Berman, Department of Marine Sciences, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Haifa, Mt Carmel, 8 Haifa 3498838, Israel. [email protected] 9 Moshe Nathan, Faculty of Life Sciences, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, 52900, Israel. Email: 10 [email protected] 11 12 Daniel Weihs, Faculty of Aerospace Engineering and Autonomous Systems Program, Technion, Haifa, 13 3200003, Israel. Email: [email protected] 14 15 16 17 18 * Corresponding author 19 20 Abstract. Pied kingfishers (Ceryle rudis) capture fish by plunge diving from hovering that may last 21 several minutes. Hovering is the most energy-consuming mode of flight and depends on active wing 22 flapping and facing headwind. The power for hovering is mass dependent increasing as the cube of 23 the size, while aerodynamic forces increase only quadratically with size. Consequently, birds above 24 a certain body mass can hover only with headwind and for very short durations. Hummingbirds are 25 referred to as the only birds capable of hovering without wind (sustained hovering) due to their 26 small size (ca. -

Birds of the South Texas Brushlands

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE BIRDS of the BY JOHN C. ARVIN SOUTH TEXAS BRUSHLANDS A Field Checklist June 2007 TPWD receives federal assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal agencies. TPWD is therefore subject to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, in addition to state anti-discrimination laws. TPWD will comply with state and federal laws prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, sex or disability. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any TPWD program, activity or event, you may contact the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Federal Assistance, 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Mail Stop: MBSP-4020, Arlington, VA 22203, Attention: Civil Rights Coordinator for Public Access. Birds of the South Texas Brushlands: A Field Checklist Second Edition INTRODUCTION he South Texas Brushlands ecoregion, also known as the Rio Grande Plain or Tamaulipan Brushlands, consists of the southern one fifth or so of the state, south of the Edwards TPlateau and west of the San Antonio River. It includes the Rio Grande Valley from about Del Rio to where the river empties into the Gulf of Mexico and the lower coast of Texas from Baffin Bay southward. This region is flat to gently rolling with a few higher hills and cliffs along the Rio Grande. This vast plain is covered mostly with a dense growth of low thorny trees, shrubs and cacti.