Serengeti Highway: Roadblocks to Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13 Day Best of Uganda, Tanzania and Zanzibar LUXURY

www.manyaafricatours.com 13 Day Best of Uganda, Tanzania & Zanzibar Luxury Safari This 13 day tour combines the lush greenery and biodiversity of Uganda with the teeming wildlife of Tanzania and the Arab-influenced Indian Ocean island of Zanzibar. Tanzania’s Serengeti and Ngorongoro Crater are incomparable in terms of vast landscapes and wildlife numbers. The tour commences with the challenging trek to see Uganda’s gorillas and ends with rest and relaxation on Zanzibar’s white beaches. From its source in Lake Victoria, the River Nile crosses the Rift Valley to give Uganda a dazzling range of unique habitats. Uganda’s resulting beauty, natural wonders and biodiversity have impressed generations of travelers. Visitors return for Uganda’s welcoming people and temperate climate. Uganda’s most coveted natural attractions include the endangered Mountain Gorilla, Chimpanzees and over 1,000 species of birds. Uganda’s diverse habitats have enthralled wildlife-watchers, and seasoned African Safari-goers, for decades. Manya Africa Tours | www.manyaafricatours.com | [email protected] Tel +256 (0) 775 554791 / +256 (0) 777 195894 Plot 3, Lubobo Close, Muyenga, Kampala, Uganda Member of AUTO Association of Uganda Tour Operators www.manyaafricatours.com 13 Day Best of Uganda, Tanzania & Zanzibar Luxury Safari Hikers and mountain climbers congregate in the Rwenzori Mountains as well as in Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, which also boasts three major peaks. A comparatively small country, Uganda has won many accolades including Lonely Planet number one destination to visit in 2012. Tanzania’s Serengeti is known as one of the ‘Seven Natural Wonders of Africa.’ Game-viewing includes: huge buffalo herds and thousands of antelope. -

Live Your Dreams

Karibu Tanzania 2018 | Edition BUSHWIDE African Safaris Inside, Insight To Tanzania Attractions Live Your All About Mount Kilimanjaro Climbing Dreams INSIDE KILIMANJARO ROUTES AN EXTRAORDINARY LEGACY OF EXPLORATION, WHEN YOU TRAVEL WITH US ! | www.bushwide.com Karibu BushWide African Safaris About Us Kundael Managing Director & Owner Bushwide African Safaris AN EXTRAORDINARY specializes in safaris and LEGACY OF EXPLORATION, trekking experience in WHEN YOU TRAVEL WITH Tanzania. We have the finest US ON AN EXPEDITION, employees that can take you YOU’LL ENJOY BOUNDLESS throughout Tanzania top OPPORTUNITIES TO BE destinations and can offer you SURROUNDED BY the widest choice of itinerar- NATURAL WONDERS AND ies - from group safaris staying EXOTIC WILDLIFE, TO at superb lodges to bespoke, EXPLORE CELEBRATED tailor made safaris staying at ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES, the very best camps, TO LEARN ABOUT specialist safaris and family DIFFERENT CULTURES Swahili : Tembo safaris. AND SHARE IN LOCAL TRADITIONS. English : Elephant Page : 2 Page : 3 Next ! Tanzania National Parks Arusha National Park Serengeti National Park Ngorongoro Conservation Lake Manyara National Park Mikumi National Park Area Tarangire National Park Kilimanjaro National Park Zanzibar Island Holidays Page : 4 Page : 5 TANZANIA NATIONAL PARKS TANZANIA NATIONAL PARKS Arusha Lake Manyara National Park National Park he park is the closest one to Arusha town, the WHAT TO DO tretching for 50km along the base of the rusty- GETTING THERE safari capital of the North. The park is often gold 600-metre high Rift Valley escarpment, overlooked by safari goers, despite offering - Forest walks, numerous picnic sites. Lake Manyara is a scenic gem, with a setting By road, charter or scheduled flight from Arusha, Tthe opportunity to explore a captivating diversity of - 3-4 days Mt. -

Reviewing the Coherence and Effectiveness of Implementation of Multilateral Biodiversity Agreements in Tanzania

Stockholm Environment Institute, Project Report – 2014 Reviewing the coherence and effectiveness of implementation of multilateral biodiversity agreements in Tanzania Jacqueline Senyagwa, Stacey Noel Reviewing the coherence and effectiveness of implementation of multilateral biodiversity agreements in Tanzania Jacqueline Senyagwa, Stacey Noel Reference: Senyagwa, J., Noel, S. 2014. Reviewing the coherence and effectiveness of implementation of multilateral biodiversity agreements in Tanzania. Project Report, SEI Africa, Nairobi: 41 p. Project No 41064 Stockholm Environment Institute Africa Centre World Agroforestry Centre United Nations Avenue, Gigiri P.O. Box 30677 Nairobi, 00100 Kenya www.sei-international.org/africa Photo: Shutterstock Lay-out: Tiina Salumäe ISBN 978-9949-9501-7-1 (pdf) January 2013 – February 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms and Abbreviations.................................................................................................................................................6 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................................6 List of Tables ..............................................................................................................................................................................................6 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................7 -

Passion for Polo Passion for Polo

MAY 2013 | VOL 1 ISSUE 4 | N2,000 | £8 Adventures in Luxury Claire Tomlinson Polo’s First Lady Royal Polo Players !e Sport of Kings Marwan Chatila Bond Street’s Most Discreet Jeweller Sayyu Dantata !"hchukker.com !"hchukkermagazine.com Passion for polo 62 82 ContentsMAY 2013 | VOL 1 ISSUE 4 7 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 32 PASSION FOR POLO Ahmed Dasuki How photographer Tony Ramirez 16 turned his passion into a business 9 EDITOR’S WELCOME Funmi Oladeinde-Ogbue 36 GINGER BAKER "e Cream drummer’s THE SEASON Nigerian polo odyssey AT FIFTH CHUKKER 38 KOLA ALUKO 10 ETISALAT AFRICAN Entrepreneur Kola Aluko PATRONS CUP on sport and business All the action from this 40 ROYALTY IN POLO prestigious event Who’s Who in today’s royal players 16 SEEN AT FIFTH CHUKKER Who’s Who in the In Crowd UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL 18 NWANKWO KANU 45 MUSTAPHA SHERIFF Fi!h Chukker’s new “I appreciate the support Charity Ambassador I have had along the way.” 20 COMMISSIONING OF 46 OSA COOKEY THE ADAMU ATTA “I have had a special bond PRIMARY SCHOOL with horses since I was a child.” "e remodelled Fi!h Chukker-funded 48 HADI SIRIKA primary school opens its doors “"e thrill of playing is so special and ful#lling.” POLO PEOPLE 50 SANI UMAR 22 GENERAL HASSSAN KATSINA “I love the thrills that go with riding.” Remembering the legendary polo-playing General ART IN FOCUS 26 PASSION FOR POLO 52 NIC FIDDIAN!GREEN Sayyu Dantata Horse sculptor extraordinaire 28 WOMEN IN POLO 56 KELECHI AMADI!OBI Claire Tomlinson’s trailblazing career Nigeria’s fashion photography genius 30 THE INAUGURAL AFRICAN -

No Longer Spotless

by Steve Folkman, AHA director Despite unaccommodating weather and determined poachers, my ultimate hunting experience reached its pinnacle on Day 14. I was able to take a big, beautiful leopard. Standing in Tanzania, over Jill’s left shoulder is Rwanda and to her right is Uganda. A valley in the middle divides the two. s I sat in the grass leopard While the weather was typical As I lifted it to unchamber the This particular quest started blind, I couldn’t help but Africa — 90s during the day and round he whispered, “In the in Chicago on Sept. 21. Mom, A roll through my mind 70s at night — it rained every hole.” I had not sensed the Jill and I flew to Amsterdam the events that had passed afternoon in this beautifully approaching leopard. The bou and then on to Kilimanjaro during the last 14 days. I was green vegetative corner of bou birds cried in the distance International Airport in Arusha, starting to wonder if I was Tanzania, causing the leopards to and the weavers quickly left Tanzania, Africa. going to get an opportunity at a sit tight like barn cats in a storm. their perch above us. I slid the After two long flights, more leopard, any leopard, let alone The “boys” (safari staff) had rifle through the oval hole in than 23 hours of travel and eight a big one. I kept thinking about set bait the day before, and as the grass blind and focused hours of time change, we were what Raoul told me when we luck would have it, a hungry through the scope. -

Culture and Wildlife of Tanzania

Africa culture and wildlife of tanzania trip highligh ts Explore Serengeti National Park and try to spot the Big Five Behold the large Elephant population, baobab trees and incredible views of Tarangire National Park Journey to Lake Manyara National Park, known for its large flocks of flamingos and elusive tree climbing lions Wildlife encounters in the Ngorongoro Crater Take in the rich cultural heritage of Tanzania’s various tribal groups including the Masai, Hadzabe and Datoga Trip Duration 10 days Trip Code: TWE Grade Adventure touring Activities Adventure Touring, Wildlife Safari Summary 10 day trip, 6 nights permanent safari camp, 2 nights safari lodge, 1 night hotel welcome to why travel with World Expeditions? Our extra attention to detail and seamless operations on the ground World Expeditions ensure that you will have a memorable experience in Africa. We take Thank you for your interest in our Culture and Wildlife of Tanzania every precaution to ensure smooth logistics, our vehicles are the best trip. At World Expeditions we are passionate about our off the beaten available on the market. Most importantly, our adventures have always track experiences as they provide our travellers with the thrill of sought to benefit the local peoples we interact with, safeguard the coming face to face with untouched cultures as well as wilderness ecosystems we explore and contribute to the sustainability of travel in regions of great natural beauty. We are committed to ensuring that the regions we experience. You will be accompanied by local guides our unique itineraries are well researched, affordable and tailored for whose knowledge and passion for wildlife will add a unique dimension the enjoyment of small groups or individuals ‑ philosophies that have to your trip. -

Elephant Trophy Imports, Part 6

IMPORT PERMIT • T~ ------ :,;,.,,..;.;.~--~---...,.,_----.......__ ~.._.~ +s..Purpc)ff :qf -......._-,----,.::---~---"',-,...--..=..1_;__~- MUST C0Mf>lY \YITM A.TTA.CHEO GeNEAALPERMIT COHDITlONS. .__~~.....,..----S.~~H 6. U. Sf>EClt,lef(6) tMY NOT,BE SOU> OR lMNSfERRED fOltANV ~NCW. REMUHEAA1l()N. U.S. FlSH AND Wtl..Dl..iFE SER\llCE OMSIONa~AlJTt«)RJTY SEE ATTACtiED PAGE-2 FOR.ADDITIONAL CONDIT!~. 4401 N. FAIRFAX ORJVE ROOM212 THJS AMENDS AND REPLACES 12US88593A/9 ISSUED ARLINGTON, VA 22203-3247 11/01/2012. '-AfayrlQlbe ~ for ~ For live Bf'limals, Ol'lly V9lid ~$c:ommerdllJ 09/12/2013 If th& nmport oomply ~Ill tJie CfTES Gufdelinfn for luulng Oate TrapsportdUveAnffna}s or, in t/1($ C&Se olairtnmspo,t, wfth IATA Llw AnimlJ/s R~ --......----- Endangered Act of 1973 (16 '(511 seq.) AUTHORITY: s~ use ~ 1 718. C~ Name and Saentfflc""name (genus and 9. Descr1i>tlon of Part or Dertv11tiva, including ldenlitylng marfts,~ 10~odlxNo 'and - -- ~) of Anina! 0( Planl °' numbers (age/ax if liw) Source ~~ - NO Sde!llfficl: Name PAtffi'IEAA PAAOUS Page2 of2 ~S:'l' IMPORT'I,OUG1i$A:d)~S10NATED PORT AS LISTED IN CONDITION'lO. OF -GENERA!.; -P~Pf eoNDimIONS. , ' J.. • (J.S. TIIR.liATENa.b SPECIES: TUSKS MUST BE MARKED AS PER [50 CFR 17.40(e)]. IN AecbIIDANGE W1.}.!H tJtE AFRICAN ELEPHANT CONSERVATION ACT, RA w ~2~~. ~~~IijG SEOR'r-.ffUNTED:ITTlOPHlES IBAT ARE WHOLLY OR PARTIALLY IVORY, MAY N9~01IT.ED FROM T8B U.S. BL~T MUST NOT HA VE BEEN TAKEN FROM ANY MORA TORJUM AREA INCLUDING LONGIDO,CONI'ROLLED HUNTING AREA (CHA). - f ,I U.S. -

Hakuna Matata - Family Tanzania Safari

HAKUNA MATATA - FAMILY TANZANIA SAFARI Classic Africa Safari Holiday for the family, Ngorongoro Crater, Lake Manyara and Tarangire, ending with R&R on Zanzibar See herds of elephants, zebra and wildebeest in some of Tanzania’s finest parks Search for rhino, lion, leopard, buffalo and elephant in the Ngorongoro Crater Walking safari in Arusha NP and an introduction to Tinga Tinga painting Zanzibar - enjoy quality family time on the white sandy beaches of this paradise island HOLIDAY CODE FTS Tanzania, Family, Wildlife, 9 Days 8 nights hotel with swimming pool, 8 breakfasts, 4 lunches, 5 dinners, max group size: 10, game drives and safari / walking safari (1-2hrs) / big five / kilimanjaro views / r&r on zanzibar VIEW DATES, PRICES & BOOK YOUR HOLIDAY HERE www.keadventure.com UK: +44(0) 17687 73966 US (toll-free): 1-888-630-4415 PAGE 2 HAKUNA MATATA - FAMILY TANZANIA SAFARI Introduction This Tanzania safari holiday is a true gem, and is especially designed for the family traveller. We start our adventure visiting Arusha National Park, seeing acrobatic black and white colobus monkeys and have an exciting walking safari with the ranger amongst the giraffe and zebra. In this special forest ecosystem the ranger will teach us interesting nuggets about the wildlife and geography at the foot of Mt Meru and Kilimanjaro. We then have game drives in Lake Manyara National Park famous for its lions lounging in the Umbrella Thorn trees and herds of elephant, buffalo, zebra, wildebeest and giraffe. Breaking up the game drives we have a session with a local artist having a go at a fun Tinga Tinga painting. -

A Topological Study of Tarangire, Northern Tanzania, 1890-2000

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Human Geography No. 21 Becoming Wilderness A topological study of Tarangire, Northern Tanzania, 1890 - 2000 Camilla Årlin ' !" #!"! $%& ' () $* +!""%,)!$ -)$% #!"! .! *) +Q! 01 0 !R$%3 4 Abstract Based on field and archival research, Becoming Wilderness analyses the fluid constructs of game preservation and their affect within networks and landscapes to the west of Tarangire National Park, Northern Tanzania from the late 19th Century until the present. The initial query of this thesis is how and why Tarangire comes to be separated as different from its surrounding (on the map and within policy) and what this has entailed for what is ‘within’ and ‘outside’. This thesis is written to add to the understanding of how ‘one of Tanzania’s most spectacular wilderness areas’ was created, in order to problematize and deepen the understanding of the factual peo- ple/park conflicts and entanglements existing there today. Through a topo- logical investigation, it shows Tarangire’s transformation from peripheral to central and the simultaneous transformation of peopled landscapes from central to borderlands. Based on interviews, focus groups and archival re- search the thesis firstly investigates the transformation of peopled land- scapes to the west of Tarangire National Park. Secondly it analyses the al- ternations in the tsetse geography that has previously been claimed to be the root cause behind the creation of the park, pointing to the fluid and rela- tional character of tsetse landscapes. Thirdly, this thesis queries the notion of an ‘imposition of wilderness’ and suggests that vast tracts of Tanzania’s protected areas have in fact gradually become wilderness within heteroge- neous networks, rooting themselves in ways that are far more tricky to op- pose than had they suddenly been imposed. -

National Forestry Resources Monitoring and Assessment

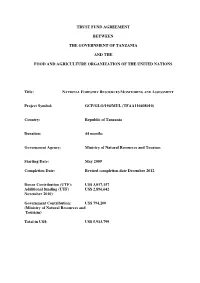

TRUST FUND AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF TANZANIA AND THE FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Title: NATIONAL FORESTRY RESOURCES MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT Project Symbol: GCP/GLO/194/MUL (TFAA110408010) Country: Republic of Tanzania Duration: 44 months Government Agency: Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism Starting Date: May 2009 Completion Date: Revised completion date December 2012 Donor Contribution (UTF): US$ 3,017,157 Additional funding (UTF) US$ 2,896,642 November 2010) Government Contribution: US$ 794,200 (Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism) Total in US$: US$ 5,913,799 Executive Summary In Tanzania, the state and trends of the forestry resources are largely unknown. The existing information is fragmentary and outdated. It is mainly constrained by the lack of institutional capacity. Under the National Forest Programme of Tanzania, the national forestry resources monitoring and assessment (NAFORMA) was identified as a priority activity for the Forest and Beekeeping Division (FBD) of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (MNRT). The results of NAFORMA are needed to support the national policy processes. Yet, the demand of the stakeholders in Tanzania for data and information on the state of the forestry resources is continuously expanding. This project is planned to develop complete and sound baseline information on the forest and tree resources, assist the FBD to set up a specialised structure and put in place a long term monitoring system of the forestry ecosystems. It will also introduce policy relevant and holistic and integrated approach to forestry resources assessment that addresses all domestic needs of information as well as the international reporting requirements, thereby being able to provide data and information on the sub-sector to users (both local and international) on timely and regular basis. -

The Government of the United Republic of Tanzania Note

THIRD UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON THE LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES Brussels, 14-20 May 2001 Country presentation by THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA NOTE The views expressed in this document are those of the Government concerned. The document is reproduced in the form and language in which it has been received. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA ACTION PROGRAMME FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA 2001 – 2010 Presentation of the Government of The United Republic of Tanzania to the Third United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries, Brussels, 14-20 May, 2001 NOTE This report has been prepared by the President's Office, Planning Commission, following consultations with members of the National Preparatory Committee consisting of Vice President's Office; Ministries of Agriculture and Food Security; Marketing and Co-operatives; Water and Livestock Development; Community Development, Women Affairs and Children; Finance; Foreign Affairs and International Co-operation; Industry and Trade; Regional Administration and Local Government; the Bank of Tanzania; Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture; Researchers from the University of Dar es Salaam; Tanzania Private Sector Foundation, Confederation of Tanzania Industries; Tanzania Federation of Co-operative Unions; Tanzania Investment Centre; NGOs (including the Tanzania Gender Network Programme) as well as Local Development Partners. Technical support was provided by the European Union. -

Namibia – Philosophy on Hunting and Wildlife

African Indaba e-Newsletter, Vol. 1. No. 6 Page 1 AFRICAN INDABA Volume 1, Issue No 6 e-Newsletter November 2003 Dedicated to the People and Wildlife of Africa 26th that “Aids may be driving the African lion into extinc- 1 Another debate – this time tion” and continued to state “scientists reporting a devastating col- lapse of the African lion population from 230 000[sic] in 1980 to fewer the African Lion than 20 000 now, the decline has traditionally been blamed on loss of By Gerhard R Damm natural habitat and hunting. But advances in virology and groundbreak- ing field research suggest large numbers of lions could be dying from In Vol 1/2 the article “Safari Hunting of Lion” contained AIDS because their immune system has been destroyed by lion lentivirus, a summary of papers which Karyl Whitman and Petri Viljoen the lion version of HIV.” In the same article, Briton Kate presented to the African Lion Working Group (ALWG) in Nicholls and her Dutch partner Pieter Kat even argued that 2002. I started my introduction that “the real or perceived the African lion figure to be close to 15 000. And the UK’s 3 th decline in lion populations in sub-Saharan Africa is not the Independent Digital News headlined on October 8 “Rich issue”. Recent media reports, like those published on the web Tourist trophy hunters are wiping out African lion population, conserva- 1 by the BBC News World Edition on October 7th and in tionists warn” (guess who was the quoted “leading British scien- New Scientist Magazine on September 20th have proved me tist”).