UNDERESTIMATING URBANISATION2 in Transitional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

Spatio-Temporal Flood Analysis Along the Indus River, Sindh, Punjab

p !( !( 23 August 2010 !( FL-2010-000141-PAK S p a t i o - Te m p o r a l F!( lo o d A n a l y s i s a l o n g t h e I n d u s R i v e r, S i n d h , P u n j a b , K P K a n d B a l o c h i s t a n P r o v i n c e s , P a k i s t a n p Version 1.0 !( This map shows daily variation in flo!(od water extent along the Indus rivers in Sindph, Punjab, Balochistan and KPK Index map CHINA p Crisis Satellite data : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map Scale for 1:1,000,000 Map prepared by: Supported by: provinces based on time-series MODIS Terra and Aqua datasets from August 17 to August 21, 2010. Resolution : 250m Legend 0 25 50 100 AFGHANISTAN !( Image date : August 18-22, 2010 Result show that the flood extent isq® continously increasing during the last 5 days as observed in Shahdad Kot Tehsil p Source : NASA Pre-Flood River Line (2009) Kilometres of Sindh and Balochistan provinces covering villages of Shahdad, Jamali, Rahoja, Silra. In the Punjab provinces flood has q® Airport p Pre-flood Image : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map layout designed for A1 Printing (36 x 24 inch) !( partially increased further in Shujabad Tehsil villages of Bajuwala Ti!(bba, Faizpur, Isanwali, Mulana)as. Over 1000 villages !( ® Resolution : 250m Flood Water extent (Aug 18) p and 100 towns were identified as severly affepcted by flood waters and vanalysis was performed using geospatial database ® Heliport !( Image date : September 19, 2009 !( v !( Flood Water extent (Aug 19) ! received from University of Georgia, google earth and GIS data of NIMA (USGS). -

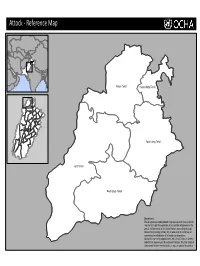

Reference Map

Attock ‐ Reference Map Attock Tehsil Hasan Abdal Tehsil Punjab Fateh Jang Tehsil Jand Tehsil Pindi Gheb Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Bahawalnagar‐ Reference Map Minchinabad Tehsil Bahawalnagar Tehsil Chishtian Tehsil Punjab Haroonabad Tehsil Fortabbas Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. p Bahawalpur‐ Reference Map Hasilpur Tehsil Khairpur Tamewali Tehsil Bahawalpur Tehsil Ahmadpur East Tehsil Punjab Yazman Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

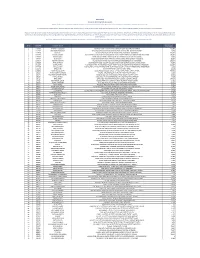

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Capacity Building of Sugarcane Farmers Regarding Integrated Pest Management in Punjab

Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. (2020). 7(4): 34-45 International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences ISSN: 2348-8069 www.ijarbs.com DOI: 10.22192/ijarbs Coden: IJARQG(USA) Volume 7, Issue 4 -2020 Research Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22192/ijarbs.2020.07.04.003 Capacity building of sugarcane farmers regarding Integrated Pest Management in Punjab R.M. Amir and Hafiz Ali Raza* 1Institute of Agri. Extension, Education and Rural Development, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan *Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Extreme changes in climate affecting the environment very adversely. Among many reasons behind these climatic variations such as hot weather, unexpected rainfall and a higher concentration of carbon dioxide. Blind use of pesticides is one of the main reasons for climate change which directly affects the food safety and human nutrition. It is happened due to unawareness and no adoption of integrated pest management (IPM). Therefore, the current project is planned for the capacity building of sugarcane farmers regarding integrated pest management in Punjab. The project was conducted at two tehsils of Punjab province named Sadiqabad and Chiniot. Tehsil Sadiqabad was selected from District RYK whereas tehsil Chiniot was selected from Faisalabad division. From each of the selected Tehsils, two villages were selected randomly. In this way, a total of four (4) villages were selected randomly through this procedure. Thus, from each of the villages, 30 farmers were selected which were later trained by experts (through seminars) for particular awareness. In this way, a total of 120 sugarcane farmers was given training through this project. -

Village List of Multan Division , Pakistan

Cel'.Us 51·No. 30B (I) M.lnt.6-19 300 CENSUS OF PAKISTAN, 1951 VILLAGE LIST PUNJAB Multan Division OFFICE Of THE PROVINCIAL · .. ·l),ITENDENT CENSUS, J~ 1952 ,~ :{< 'AND BAHAWALPUR, P,IC1!iR.. 10 , , FOREWOf~D This Village Ust has been prepared from the material collected in con nection with the Census of Pakistan, 1951. The object of the List is to present useful information about our villages. It was considered that in a predominantly rural country like Pakistan, reliable village statistics should be available and it is hoped that the Village List will form the basis for the continued collection of such statistics. A summary table of the totals for each tehsil showinz its area to the nearest square mile, and its population and the number of houses to the nearest hundred is given on page I together with the page number on which each tehsil begins. The general village table, which has been compiled district-wise and arranged tehsil-wise, appears on page 3 et seq. Within each tehsll th~ Revenue Kanungo ho/qas are shown according to their order in the census records. The Village in which the Revenue Kanungo usually resides is printed in bold type at the beginning of each Kanungo halqa and the remaining villages comprising the halqas, are shown thereunder in the order of their revenue hadbast numbers, which are given in column a. Rakhs (tree plantations) and other similar area,. even where they are allotted separate revenue hadbast nurY'lbcrs have not been shown as they were not reported in the Charge and Household summaries, to be inhabited. -

S.R.O. No.---/2011.In Exercise Of

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 9, 2021 39 S.R.O. No.-----------/2011.In exercise of powers conferred under sub-section (3) of Section 4 of the PEMRA Ordinance 2002 (Xlll of 2002), the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority is pleased to make and promulgate the following service regulations for appointment, promotion, termination and other terms and conditions of employment of its staff, experts, consultants, advisors etc. ISLAMABAD SATURDAY, JANUARY 9, 2021 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY AND RESEARCH NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 6th January, 2021 S. R. O. (17) (I)/2021.—In exercise of the powers conferred by section 15 of the Agricultural Pesticides Ordinance, 1971 (II of 1971), and in supersession of its Notifications No. S.R.O. 947(I)/2002, dated the 23rd December, 2002, S.R.O. 1251 (I)2005, dated the 15th December, 2005, S.R.O. 697(I)/2005, dated the 28th June, 2006, S.R.O. 604(I)/2007, dated the 12th June, 2007, S.R.O. 84(I)/2008, dated the 21st January, 2008, S.R.O. 02(I)/2009, dated the 1st January, 2009, S.R.O. 125(I)/2010, dated the 1st March, 2010 and S.R.O. 1096(I), dated the 2nd November, 2010. The Federal Government is pleased to appoint the following officers specified in column (2) of the Table below of Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab, to be inspectors within the local limits specified against each in column (3) of the said Table, namely:— (39) Price: Rs. -

Latest Trends in Enrolment June 2015

Latest Trends in Enrolment June 2015 August 12, 2015 Agenda Detailed Nielsen analysis Observations from the field 1 Agenda Detailed Nielsen analysis Observations from the field 2 Enrolment for 5-9 year olds has increased by 1.1% School participation rate 5-9 year olds (%) 90.4% 89.3% 1.1% 88.2% 86.8% 86.1% 85.9% 84.8% Nov-11 Jun-12Nov-12 Jun-13 Nov-13 Nov-14 Jun-15 SOURCE: Nielsen Household Survey– November 2011 to June 2015 3 Enrolment ( Nov 2011 - Jun 2015) School participation rate – Urban Areas 5-9 year olds (%) 94.7% 92.9% 93.1% 93.1% 92.7% 92.6% 92.2% Nov-11 Jun-12 Nov-12 Jun-13 Nov-13 Nov-14 Jun-15 School participation rate – Rural Areas 5-9 year olds (%) 88.7% 87.8% 86.5% 84.4% 83.5% 83.2% 81.9% Nov-11 Jun-12 Nov-12 Jun-13 Nov-13 Nov-14 Jun-15 SOURCE: Nielsen Household Survey– November 2011 to June 2015 Margin of Error < 4% with a 95 % confidence interval 4 Enrolment has increased significantly over the last 4 years, with a proportionate increase observed for across all age groups Enrolment Percent Jun 2015 100% Nov 2011 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 0 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Age No. of years SOURCE: Nielsen Household Survey November 2011; June 2015 Margin of Error < 3.1% with a 95 % confidence interval 5 35 districts in Punjab show improvement since November 2011 District % Change since November 2011 Rahim Yar Khan 15.4% Lodhran 13.1% Bahawalnagar 13.0% Bahawalpur 12.1% Pakpattan 10.9% Sheikhupura 9.9% <3.1 % Layyah 9.7% >3.1% Sahiwal 9.2% Mianwali 9.1% Sargodha 9.0% 25 districts show a % Khushab 8.2% change -

Sr.No ACCOUNT Customer Name Address Balance As of 03/12/2020

Public Notice Auction of Gold Ornaments & Valuables Finance facilities were extended by JS Bank Limited to its customers mentioned below against the security of deposit and pledge of Gold ornaments/valuables. The customers have neglected and failed to repay the finances extended to them by JS Bank Limited along with the mark-up thereon. The current outstanding liability of such customers is mentioned below. Notice is hereby given to the under mentioned customers that if payment of the entire outstanding amount of finance along with mark-up is not made by them to JS Bank Limited within 15 days of the publication of this notice, JS Bank Limited shall auction the Gold ornaments/valuables after issuing public notice regarding the date and time of the public auction and the proceeds realized form such auction shall be applied towards the outstanding amount due and payable by the customers to JS Bank Limited. No further public notice shall be issued to call upon the customers to make payment of the outstanding amounts due and payable to JS Bank Limited as mentioned hereunder: Balance as of Sr.No ACCOUNT Customer Name Address 03/12/2020 1 1148605 NAVEED ALI SOOMRO HOUSE NO 7 489 A SHE EDKI KHOHI SIDIQUE MORI SHIKAR PUR SHIKARPUR 268,787 2 1312357 MOHAMMAD MANSHA VPO KHAS KUTYALA SHA IKAIN BACHER MANDI BAHA DU DIN MANDI BAHAUDDIN 13,938 3 1259818 RAJAB ALI QUAID EAZAM ROAD HAB IB CHOWK NEAR JACOBABAD JACOBABAD 753,623 4 1475296 WAQAR HUSSAIN JAJJA AUR PO KHAS KO T SHER MUHAMMAD TEH PHALIA DIS TT MANDI BAHAUDDIN MANDI BAHAUDDIN 181,820 5 1184967 -

Province Wise Provisional Results of Census - 2017

PROVINCE WISE PROVISIONAL RESULTS OF CENSUS - 2017 ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS POPULATION 2017 POPULATION 1998 PAKISTAN 207,774,520 132,352,279 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA 30,523,371 17,743,645 FATA 5,001,676 3,176,331 PUNJAB 110,012,442 73,621,290 SINDH 47,886,051 30,439,893 BALOCHISTAN 12,344,408 6,565,885 ISLAMABAD 2,006,572 805,235 Note:- 1. Total Population includes all persons residing in the country including Afghans & other Aliens residing with the local population 2. Population does not include Afghan Refugees living in Refugee villages 1 PROVISIONAL CENSUS RESULTS -2017 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA District Tehsil POPULATION POPULATION ADMN. UNITS / AREA Sr.No Sr.No 2017 1998 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA 30,523,371 17,743,645 MALAKAND DIVISION 7,514,694 4,262,700 1 CHITRAL DISTRICT 447,362 318,689 1 Chitral Tehsil 278,122 184,874 2 Mastuj Tehsil 169,240 133,815 2 UPPER DIR DISTRICT 946,421 514,451 3 Dir Tehsil 439,577 235,324 4 *Shringal Tehsil 185,037 104,058 5 Wari Tehsil 321,807 175,069 3 LOWER DIR DISTRICT 1,435,917 779,056 6 Temergara Tehsil 520,738 290,849 7 *Adenzai Tehsil 317,504 168,830 8 *Lal Qilla Tehsil 219,067 129,305 9 *Samarbagh (Barwa) Tehsil 378,608 190,072 4 BUNER DISTRICT 897,319 506,048 10 Daggar/Buner Tehsil 355,692 197,120 11 *Gagra Tehsil 270,467 151,877 12 *Khado Khel Tehsil 118,185 69,812 13 *Mandanr Tehsil 152,975 87,239 5 SWAT DISTRICT 2,309,570 1,257,602 14 *Babuzai Tehsil (Swat) 599,040 321,995 15 *Bari Kot Tehsil 184,000 99,975 16 *Kabal Tehsil 420,374 244,142 17 Matta Tehsil 465,996 251,368 18 *Khawaza Khela Tehsil 265,571 141,193 -

S. No. Bank Name Office Type* Name Tehsil District Province Address

List of Selected Operational Branches Office S. No. Bank Name Name Tehsil District Province Address License No. Type* BRL-20115 dt: 19.02.2013 1 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Lahore-0001 Lahore City Tehsil Lahore Punjab 87, Shahrah-E-Quaid-E-Azam, Lahore (Duplicate) Plot No: Sr-2/11/2/1, Office No: 105-108, Al-Rahim Tower, I.I. Chundrigar Road, BRL-20114 dt: 19.02.2013 2 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Karachi-0002 Karachi South District Karachi Sindh Karachi (Duplicate) BRL-20116 dt: 19.02.2013 3 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Branch Peshawar Peshawar Tehsil Peshawar KPK Property No: Ca/457/3/2/87, Saddar Road, Peshawar Cantt., (Duplicate) BRL-20117 dt: 19.02.2013 4 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Br. Quetta-0004 Quetta City Tehsil Quetta Balochistan Ground Floor, Al-Shams Hotel, M.A. Jinnah Road, Quetta. (Duplicate) Plot No: 35/A, Munshi Sher Plaza, Allama Iqbal Road, New Mirpur Town, Mirpur BRL-17606 dt: 03.03.2009 5 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Branch Mirpur Mirpur Mirpur AJK (Ak) (Duplicate) Main Branch, Hyderabad.- 6 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Hyderabad City Taluka Hyderabad Sindh Shop No: 6, 7 & 8, Plot No: 475, Dr. Ziauddin Road, Hyderabad BRL-13188 dt: 04.04.1993 0006 7 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Guj-0007 Gujranwala City Tehsil Gujranwala Punjab Khewat & Khatooni: 78 Khasra No: 393 Near Din Plaza G. T. Road Gujranwala BRL-13192 dt: 14.07.1993 8 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Main Fsd-0008 Faisalabad City Tehsil Faisalabad Punjab Chiniot Bazar, Faisalabad BRL-13196 dt: 30.09.1993 9 Soneri Bank Limited Branch Sie Br.