The White Mustang of the Prairies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tara Stud's Homecoming King

TUESDAY, 15 DECEMBER 2020 DEIRDRE TO VISIT GALILEO IN 2021 TARA STUD'S A new direction in the extraordinary odyssey of the Japanese HOMECOMING KING mare Deirdre (Jpn) (Harbinger {GB}BReizend {Jpn, by Special Week {Jpn}) began on Monday when the 6-year-old left her adopted home of Newmarket to begin her stud career in Ireland. Her first mating is planned to be with Coolmore's champion sire Galileo (Ire). Bred by Northern Farm and raced by Toji Morita, Deirdre's first three seasons of racing were restricted largely to Japan, where she won five races, including the G1 Shuka Sho. She also took third in the G1 Dubai Turf on her first start outside her native country. Following her return visit to the Dubai World Cup meeting in 2019, Deirdre travelled on to Hong Kong and then to Newmarket, which has subsequently remained her base for an ambitious international campaign. Cont. p6 River Boyne | Benoit photo IN TDN AMERICA TODAY VOLATILE SETTLING IN AT THREE CHIMNEYS By Emma Berry and Alayna Cullen GI Alfred G. Vanderbilt H. winner Volatile (Violence) is new to On part of its 70-mile journey across Ireland, the River Boyne Three Chimneys Farm in 2021. The TDN’s Katie Ritz caught up flows not far from Tara Stud in County Meath, but the stallion with Three Chimneys’ Tom Hamm regarding the new recruit. named in its honour has taken a far more meandering course Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. simply to return to source. Approaching his sixth birthday, River Boyne (Ire) (Dandy Man {Ire}) is back home from America and about to embark on a stallion career five years after he was sold by his breeder Derek Iceton at the Goffs November Foal Sale. -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

A Police Whistleblower in a Corrupt Political System

A police whistleblower in a corrupt political system Frank Scott Both major political parties in West Australia espouse open and accountable government when they are in opposition, however once their side of politics is able to form Government, the only thing that changes is that they move to the opposite side of the Chamber and their roles are merely reversed. The opposition loves the whistleblower while the government of the day loathes them. It was therefore refreshing to see that in 2001 when the newly appointed Attorney General in the Labor government, Mr Jim McGinty, promised that his Government would introduce whistleblower protection legislation by the end of that year. He stated that his legislation would protect those whistleblowers who suffered victimization and would offer some provisions to allow them to seek compensation. How shallow those words were; here we are some sixteen years later and yet no such legislation has been introduced. Below I have written about the effects I suffered from trying to expose corrupt senior police officers and the trauma and victimization I suffered which led to the loss of my livelihood. Whilst my efforts to expose corrupt police officers made me totally unemployable, those senior officers who were subject of my allegations were promoted and in two cases were awarded with an Australian Police Medal. I describe my experiences in the following pages in the form of a letter to West Australian parliamentarian Rob Johnson. See also my article “The rise of an organised bikie crime gang,” September 2017, http://www.bmartin.cc/dissent/documents/Scott17b.pdf 1 Hon. -

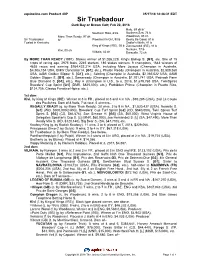

Sir Truebadour

equineline.com Product 40P 05/17/18 18:46:31 EDT Sir Truebadour Dark Bay or Brown Colt; Feb 22, 2016 Halo, 69 dk b/ Southern Halo, 83 b Northern Sea, 74 b More Than Ready, 97 dk Woodman, 83 ch Sir Truebadour b/ Woodman's Girl, 90 b Becky Be Good, 81 b Foaled in Kentucky Sadler's Wells, 81 b King of Kings (IRE), 95 b Zummerudd (IRE), 81 b Kivi, 00 ch Nureyev, 77 b Vilikaia, 82 ch Baracala, 72 ch By MORE THAN READY (1997). Stakes winner of $1,026,229, King's Bishop S. [G1], etc. Sire of 15 crops of racing age, 2975 foals, 2245 starters, 185 stakes winners, 9 champions, 1643 winners of 4855 races and earning $164,432,214 USA, including More Joyous (Champion in Australia, $4,506,154 USA, BMW Doncaster H. [G1], etc.), Phelan Ready (Champion in Australia, $2,809,560 USA, AAMI Golden Slipper S. [G1], etc.), Sebring (Champion in Australia, $2,365,522 USA, AAMI Golden Slipper S. [G1], etc.), Samaready (Champion in Australia, $1,701,741 USA, Patinack Farm Blue Diamond S. [G1], etc.), Roy H (Champion in U.S., to 6, 2018, $1,679,765 USA, TwinSpires Breeders' Cup Sprint [G1] (DMR, $825,000), etc.), Forbidden Prince (Champion in Puerto Rico, $124,756, Clasico Fanatico Hipico, etc.). 1st dam Kivi, by King of Kings (IRE). Winner at 3 in FR , placed at 3 and 4 in NA , $50,285 (USA), 2nd La Coupe des Pouliches. Dam of 8 foals, 7 to race, 5 winners-- REGALLY READY (g. -

Electronic Supplementary Material - Appendices

1 Electronic Supplementary Material - Appendices 2 Appendix 1. Full breed list, listed alphabetically. Breeds searched (* denotes those identified with inherited disorders) # Breed # Breed # Breed # Breed 1 Ab Abyssinian 31 BF Black Forest 61 Dul Dülmen Pony 91 HP Highland Pony* 2 Ak Akhal Teke 32 Boe Boer 62 DD Dutch Draft 92 Hok Hokkaido 3 Al Albanian 33 Bre Breton* 63 DW Dutch Warmblood 93 Hol Holsteiner* 4 Alt Altai 34 Buc Buckskin 64 EB East Bulgarian 94 Huc Hucul 5 ACD American Cream Draft 35 Bud Budyonny 65 Egy Egyptian 95 HW Hungarian Warmblood 6 ACW American Creme and White 36 By Byelorussian Harness 66 EP Eriskay Pony 96 Ice Icelandic* 7 AWP American Walking Pony 37 Cam Camargue* 67 EN Estonian Native 97 Io Iomud 8 And Andalusian* 38 Camp Campolina 68 ExP Exmoor Pony 98 ID Irish Draught 9 Anv Andravida 39 Can Canadian 69 Fae Faeroes Pony 99 Jin Jinzhou 10 A-K Anglo-Kabarda 40 Car Carthusian 70 Fa Falabella* 100 Jut Jutland 11 Ap Appaloosa* 41 Cas Caspian 71 FP Fell Pony* 101 Kab Kabarda 12 Arp Araappaloosa 42 Cay Cayuse 72 Fin Finnhorse* 102 Kar Karabair 13 A Arabian / Arab* 43 Ch Cheju 73 Fl Fleuve 103 Kara Karabakh 14 Ard Ardennes 44 CC Chilean Corralero 74 Fo Fouta 104 Kaz Kazakh 15 AC Argentine Criollo 45 CP Chincoteague Pony 75 Fr Frederiksborg 105 KPB Kerry Bog Pony 16 Ast Asturian 46 CB Cleveland Bay 76 Fb Freiberger* 106 KM Kiger Mustang 17 AB Australian Brumby 47 Cly Clydesdale* 77 FS French Saddlebred 107 KP Kirdi Pony 18 ASH Australian Stock Horse 48 CN Cob Normand* 78 FT French Trotter 108 KF Kisber Felver 19 Az Azteca -

120-Day Mustang Challenge Faq's

FAQ 120-Day Mustang Challenge 120-DAY MUSTANG CHALLENGE FAQ'S Where did these six mustangs come from? These horses were the offspring of wild horses managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The mothers were captured off of BLM land and taken in by Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary. The six geldings were born and raised in North Dakota on the sanctuary. Mary Behrens, in partnership with the Free Rein Foundation, has adopted the Mustangs, transported them to Huntington Beach and will jointly oversee the Mustang Challenge, with the ultimate goal of finding them loving, forever homes. Where does the Mustang come from? American mustangs are descendants of horses brought by the Spanish, beginning in the 16th century. Feral populations became established, especially in the west. These interbred to varying degrees with other breeds, for example, escaped or released ranch horses, racehorses, and other thoroughbreds. Modern populations, therefore, exhibit some variability depending on their ancestry. What are the characteristics of the American Mustang? The physical traits of wild herds can vary quite a bit, and there was a time when characteristics associated with early Spanish strains -- e.g., a short back and deep girth and dun color -- were preferred. Most are small, somewhere between 13 and 15 hands. How do Mustangs live? Mustangs live in large herds. The herd consists of one stallion, around eight females and their young, though separate herds have been known to blend when they are in danger. A female horse, or mare, and a stallion that is over six years of age lead the herd. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

From Lisheen Stud Lord Gayle Sir Gaylord Sticky Case Lord Americo Hynictus Val De Loir Hypavia Roselier Misti IV Peace Rose QUAR

From Lisheen Stud 1 1 Sir Gaylord Lord Gayle Sticky Case Lord Americo Val de Loir QUARRYFIELD LASS Hynictus (IRE) Hypavia (1998) Misti IV Right Then Roselier Bay Mare Peace Rose Rosie (IRE) No Argument (1991) Right Then Esplanade 1st dam RIGHT THEN ROSIE (IRE): placed in a point-to-point; dam of 6 foals; 3 runners; 3 winners: Quarryfield Lass (IRE) (f. by Lord Americo): see below. Graduand (IRE) (g. by Executive Perk): winner of a N.H. Flat Race and placed twice; also placed over hurdles. Steve Capall (IRE) (g. by Dushyantor (USA)): winner of a N.H. Flat Race at 5, 2008 and placed twice. 2nd dam RIGHT THEN: ran 3 times over hurdles; dam of 8 foals; 5 runners; a winner: Midsummer Glen (IRE): winner over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Big Polly: unraced; dam of winners inc.: Stagalier (IRE): 4 wins viz. 3 wins over hurdles and placed 3 times inc. 3rd Brown Lad H. Hurdle, L. and winner over fences. Wyatt (IRE): 2 wins viz. placed; also winner over hurdles and placed 5 times and winner over fences, 2nd Naas Novice Steeplechase, Gr.3. 3rd dam ESPLANADE (by Escart III): winner at 5 and placed; also placed twice over jumps; dam of 5 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners inc.: Ballymac Lad: 4 wins viz. placed at 5; also winner of a N.H. Flat Race and placed 4 times; also 2 wins over hurdles, 2nd Celbridge Extended H. Hurdle, L. and Coral Golden EBF Stayers Ext H'cp Hurdle, L. and winner over fences. -

Morgan Horses

The 12th Annual NATIONAL MORGAN HORSE SHOW Sponsored by: Saturday Evening Friday Evening 7:00 P. M. 7:00 P. M. Sunday Saturday Afternoon Afternoon 1:00 P. M. 1:00 P. M. PERFORMANCE BREED CLASSES CLASSES For Stallions and Saddle, Harness, Mares: Colts and Pleasure. Utility Fillies and Equitation THE MORGAN HORSE CLUB Watch The Foundation Breed of America Perform. TRI-COUNTY FAIR GROUNDS NORTHAMPTON, MASS. July 30, 31 and August 1, 1954 Adults $1.00 Children - under 12 - 50' A LAW FOR IT . by 1939 Vermont Legislature "There oughta be a law agin it," is a favorite expresion of Vermonters. Sometimes they reverse themselves and make a law "for it" as they did in 1939 when the legislature passed the following resolution: "Whereas, this is the year recognized as the 150th anniversa y of the famous horse 'Justin Morgan,' which horse not only established a recognized breed of horses named for a single individual, but brought fame th•tzugh his descendants to Vermont and thousands of dollars to Vermonters. "The name Morgan has come to mean beauty, spirit, and action to all lovers of the horse; and the Morgan horses fo• many years held the world's record for trotting horses, and "Whereas the Morgan blood is recognized as foundation stock for the American Saddle Horse, for the American Trotting Horse, and for the Tennessee Walking Horse. In each of these three breeds, the Morgan horse is recognized as a foundation, and therefore, with the recognition of its value to the horse b seeders of the nation, and recognition that it was in Vermont that Morgan -

Northern Dancer

LES 2000 GUINEES EUROPEENNES DE NORTHERN DANCER 2000 GUINEES Année Vainqueur Père Ascendants Paternels Père de Mère 1970 Nijinsky Northern Dancer Bull Page 1983 Lomond Northern Dancer Poker 1984 El Gran Senor Northern Dancer Buckpasser 1985 Shadeed Nijinsky Northern Dancer Damascus 1986 Dancing Brave Lyphard Northern Dancer Drone 1991 Mystiko Secreto Northern Dancer Zeddaan 1992 Rodrigo de Triano El Gran Senor Northern Dancer Hot Spark 1997 Entrepreneur Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Exclusive Native 1998 King of Kings Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Habitat 1999 Island Sands Turtle Island Fairy King Northern Dancer J O Tobin 2002 Rock of Gibraltar Danehill Danzig Northern Dancer Be My Guest 2003 Refuse to Bend Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Gulch 2004 Haafhd Alhaarth Unfuwain Northern Dancer Blushing Groom 2005 Footstepsinthesand Giant's Causeway Storm Cat Storm Bird Rainbow Quest 2006 George Washington Danehill Danzig Northern Dancer Alysheba 2007 Cockney Rebel Val Royal Royal Academy Nijinsky Known Fact 2009 Sea The Stars Cape Cross Green Desert Danzig Miswaki 2011 Frankel Galileo Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Danehill IRISH 2000 GUINEES Année Vainqueur Père Ascendants Paternels Père de Mère 1976 Northern Treasure Northfields Northern Dancer Kyrhnos 1981 Kings Lake Nijinsky Northern Dancer Baldric II 1984 Sadler' s Wells Northern Dancer Bold Reason 1988 Prince of Birds Storm Bird Northern Dancer Key To The Mint 1989 Shaadi Danzig Northern Dancer Hoist The Flag 1991 Fourstars Allstar Compliance Northern Dancer Bold Arian 1992 Rodrigo -

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers Press Event Newmarket, Thursday, June 13, 2019 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR ROYAL ASCOT 2019 Deirdre (JPN) 5 b m Harbinger (GB) - Reizend (JPN) (Special Week (JPN)) Born: April 4, 2014 Breeder: Northern Farm Owner: Toji Morita Trainer: Mitsuru Hashida Jockey: Yutaka Take Form: 3/64110/63112-646 *Aimed at the £750,000 G1 Prince Of Wales’s Stakes over 10 furlongs on June 19 – her trainer’s first runner in Britain. *The mare’s career highlight came when landing the G1 Shuka Sho over 10 furlongs at Kyoto in October, 2017. *She has also won two G3s and a G2 in Japan. *Has competed outside of Japan on four occasions, with the pick of those efforts coming when third to Benbatl in the 2018 G1 Dubai Turf (1m 1f) at Meydan, UAE, and a fast-finishing second when beaten a length by Glorious Forever in the G1 Longines Hong Kong Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin, Hong Kong, in December. *Fourth behind compatriot Almond Eye in this year’s G1 Dubai Turf in March. *Finished a staying-on sixth of 13 on her latest start in the G1 FWD QEII Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin on April 28 when coming from the rear and meeting trouble in running. Yutaka Take rode her for the first time. Race record: Starts: 23; Wins: 7; 2nd: 3; 3rd: 4; Win & Place Prize Money: £2,875,083 Toji Morita Born: December 23, 1932. Ownership history: The business owner has been registered as racehorse owner over 40 years since 1978 by the JRA (Japan Racing Association). -

The Spanish Mustang and the Long Way Home by Callie Heacock and Ernesto Valdés

The Spanish Mustang and the Long Way Home by Callie Heacock and Ernesto Valdés The evolutionary history and preservation of the Spanish the runner of aboriginal wildness, I had to trace the Age of Horse Mustang is complex; its historical importance to the Spanish- Culture that he brought not only to Western tribes but to white Mexican settlements of Texas and, ultimately, to the colonization men who took their ranges. My chief pleasure has been in telling of the American West, cannot be overstated. J. Frank Dobie, who the tales, legendary as well as factual, of Mustangs and of rides spent years researching The Mustangs and is credited with the on horses of the Mustang breed—but historical business had to best chronicles of the horses ever written, estimated that, at their come before pleasure.”2 The Mustang history in the Americas is height, over a million Mustangs ran free in Texas. In The Mus- believed to begin with the arrival of the first Europeans; how- tangs, he wrote: “To comprehend the stallions that bore conquis- ever, an intriguing twist in its evolutionary path reveals that for tadores across the Americas, I had to go back to mares beside the horses, it was a homecoming. black tents in Arabian deserts. Before I could release myself with In 1493, on Christopher Columbus’ second voyage, twenty 16 Volume 7 • Number 1 • Fall 2009 Spanish horses stepped off the ships onto the Caribbean island to the Americas. As a result, historians cited the arrival of the of Santo Domingo and within a decade, this small band had horse with Columbus as the introduction of a new species into multiplied to over sixty horses.