Hawaiian Historical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaii Been Researched for You Rect Violation of Copyright Already and Collected Into Laws

COPYRIGHT 2003/2ND EDITON 2012 H A W A I I I N C Historically Speaking Patch Program ABOUT THIS ‘HISTORICALLY SPEAKING’ MANUAL PATCHWORK DESIGNS, This manual was created Included are maps, crafts, please feel free to contact TABLE OF CONTENTS to assist you or your group games, stories, recipes, Patchwork Designs, Inc. us- in completing the ‘The Ha- coloring sheets, songs, ing any of the methods listed Requirements and 2-6 waii Patch Program.’ language sheets, and other below. Answers educational information. Manuals are books written These materials can be Festivals and Holidays 7-10 to specifically meet each reproduced and distributed 11-16 requirement in a country’s Games to the individuals complet- patch program and help ing the program. Crafts 17-23 individuals earn the associ- Recipes 24-27 ated patch. Any other use of these pro- grams and the materials Create a Book about 28-43 All of the information has contained in them is in di- Hawaii been researched for you rect violation of copyright already and collected into laws. Resources 44 one place. Order Form and Ship- 45-46 If you have any questions, ping Chart Written By: Cheryle Oandasan Copyright 2003/2012 ORDERING AND CONTACT INFORMATION SPECIAL POINTS OF INTEREST: After completing the ‘The Patchwork Designs, Inc. Using these same card types, • Celebrate Festivals Hawaii Patch Program’, 8421 Churchside Drive you may also fax your order to Gainesville, VA 20155 (703) 743-9942. • Color maps and play you may order the patch games through Patchwork De- Online Store signs, Incorporated. You • Create an African Credit Card Customers may also order beaded necklace. -

AMERICA's ANNEXATION of HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE

A LUSCIOUS FRUIT: AMERICA’S ANNEXATION OF HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE HOWARD JONES, COMMITTEE CHAIR JOSEPH A. FRY KARI FREDERICKSON LISA LIDQUIST-DORR STEVEN BUNKER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Becky L. Bruce 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the annexation of Hawaii was not the result of an aggressive move by the United States to gain coaling stations or foreign markets, nor was it a means of preempting other foreign nations from acquiring the island or mending a psychic wound in the United States. Rather, the acquisition was the result of a seventy-year relationship brokered by Americans living on the islands and entered into by two nations attempting to find their place in the international system. Foreign policy decisions by both nations led to an increasingly dependent relationship linking Hawaii’s stability to the U.S. economy and the United States’ world power status to its access to Hawaiian ports. Analysis of this seventy-year relationship changed over time as the two nations evolved within the world system. In an attempt to maintain independence, the Hawaiian monarchy had introduced a westernized political and economic system to the islands to gain international recognition as a nation-state. This new system created a highly partisan atmosphere between natives and foreign residents who overthrew the monarchy to preserve their personal status against a rising native political challenge. These men then applied for annexation to the United States, forcing Washington to confront the final obstacle in its rise to first-tier status: its own reluctance to assume the burdens and responsibilities of an imperial policy abroad. -

Hawaiian Historical Society

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY PAPERS OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY NUMBER 17 PAPERS READ BEFORE THE SOCIETY SEPTEMBER 30, 1930 PAPERS OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY NUMBER 17 PAPERS READ BEFORE THE SOCIETY , SEPTEMBER 30, 1930 Printed by The Printshop Co., Ltd. 1930 CONTENTS Page Proceedings of the Hawaiian Historical Society Meeting, September 30, 1930 _.. 5 Historical Notes- 7 By Albert Pierce Taylor, Secretary Reminiscences of the Court of Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma 17 By Col. Curtis Piehu Iaukea former Chamberlain to King Kalakaua The Adoption of the Hawaiian Alphabet 28 By Col. Thomas Marshall Spaulding, U.S.A. The Burial Caves- of Pahukaina 34 By Emma Ahuena Davis on Taylor Annexation Scheme of 1854 That Failed: Chapter Eighteen —Life of Admiral Theodoras Bailey, U.S.N ,.. 39 By Francis R. Stoddard «f (Read by Albert Pierce Taylor) - • . • Kauai Archeology 53 By Wendell C. Bennett Read before Kauai Historical Society, May 20, 1929 Burial of King Keawe '.. 63 By John P. G. Stokes PROCEEDINGS OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY MEETING SEPTEMBER 30, 1930 Meeting of the Society was called for this date, at 7:30 P. M., in the Library of Hawaii, to hear several Papers which were prepared by members on varied historical phases relating to the Hawaiian Islands. Bishop H. B. Restarick, president, in the chair; A. P. Taylor, secretary and several of the trustees, more members than usual in attendance, and many visitors present, the assembly room being filled to capacity. Bishop Restarick announced that the names of Harold W. Bradley, of Pomona, Calif., engaged in historical research in Honolulu until recently, and Bishop S. -

A Million Pounds of Sandalwood: the History of Cleopatra's Barge in Hawaii

A Million Pounds Of Sandalwood The History of CLEOPATRA’S BARGE in Hawaii by Paul Forsythe Johnston If you want to know how Religion stands at the in his father’s shipping firm in Salem, shipping out Islands I can tell you—All sects are tolerated as a captain by the age of twenty. However, he pre- but the King worships the Barge. ferred shore duty and gradually took over the con- struction, fitting out and maintenance of his fam- Charles B. Bullard to Bryant & Sturgis, ily’s considerable fleet of merchant ships, carefully 1 November expanded from successful privateering during the Re volution and subsequent international trade un- uilt at Salem, Massachusetts, in by Re t i re der the new American flag. In his leisure time, B Becket for George Crowninshield Jr., the her- George drove his custom yellow horse-drawn car- m a p h rodite brig C l e o p a t ra’s Ba r g e occupies a unique riage around Salem, embarked upon several life- spot in maritime history as America’s first ocean- saving missions at sea (for one of which he won a going yacht. Costing nearly , to build and medal), recovered the bodies of American military fit out, she was so unusual that up to , visitors heroes from the British after a famous naval loss in per day visited the vessel even before she was com- the War of , dressed in flashy clothing of his pleted.1 Her owner was no less a spectacle. own design, and generally behaved in a fashion Even to the Crowninshields, re n o w n e d quite at odds with his diminutive stature and port l y throughout the region for going their own way, proportions. -

Ad E& MAY 2 6 1967

FEBRUARY, 1966 254 &Ad e& MAY 2 6 1967 Amstrong, Richard,presents census report 145; Minister of Public Abbott, Dr. Agatin 173 Instruction 22k; 227, 233, 235, 236, Abortion 205 23 7 About A Remarkable Stranger, Story 7 Arnlstrong, Mrs. Richard 227 Adms, Capt . Alexander, loyal supporter Armstrong, Sam, son of Richard 224 of Kamehameha I 95; 96, 136 Ashford, Volney ,threatens Kalakaua 44 Adans, E.P., auctioneer 84 Ashford and Ashford 26 Adams, Romanzo, 59, 62, 110, 111, ll3, Asiatic cholera 113 Ilk, 144, 146, 148, 149, 204, 26 ---Askold, Russian corvette 105, 109 Adams Gardens 95 Astor, John Jacob 194, 195 Adams Lane 95 Astoria, fur trading post 195, 196 Adobe, use of 130 Atherton, F.C, 142 ---mc-Advertiser 84, 85 Attorney General file 38 Agriculture, Dept. of 61 Auction of Court House on Queen Street kguiar, Ernest Fa 156 85 Aiu, Maiki 173 Auhea, Chiefess-Premier 132, 133 illmeda, Mrs. Frank 169, 172 Auld, Andrew 223 Alapai-nui, Chief of Hawaii 126 Austin, James We 29 klapai Street 233 Automobile, first in islands 47 Alapa Regiment 171 ---Albert, barkentine 211 kle,xander, Xary 7 Alexander, W.D., disputes Adams 1 claim Bailey, Edward 169; oil paintings by 2s originator of flag 96 170: 171 Alexander, Rev. W.P., estimates birth mile: House, Wailuku 169, 170, 171 and death rates 110; 203 Bailey paintings 170, 171 Alexander Liholiho SEE: Kamehameha IV Baker, Ray Jerome ,photographer 80, 87, 7 rn Aliiolani Hale 1, 41 opens 84 1 (J- Allen, E.H., U.S. Consul 223, 228 Baker, T.J. -

Wao Kele O Puna Comprehensive Management Plan

Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan Prepared for: August, 2017 Prepared by: Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nālehualawaku‘ulei Nā-lehua-lawa-ku‘u-lei is a team of cultural resource specialists and planners that have taken on the responsibilities in preparing this comprehensive management for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Nā pua o kēia lei nani The flowers of this lovely lei Lehua a‘o Wao Kele The lehua blossoms of Wao Kele Lawa lua i kēia lei Bound tightly in this lei Ku‘u lei makamae My most treasured lei Lei hiwahiwa o Puna Beloved lei of Puna E mālama mākou iā ‘oe Let us serve you E hō mai ka ‘ike Grant us wisdom ‘O mākou nā pua For we represent the flowers O Nālehualawaku‘ulei Of Nālehualawaku‘ulei (Poem by na Auli‘i Mitchell, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i) We come together like the flowers strung in a lei to complete the task put before us. To assist in the preservation of Hawaiian lands, the sacred lands of Wao Kele o Puna, therefore we are: The Flowers That Complete My Lei Preparation of the Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan In addition to the planning team (Nālehualawaku‘ulei), many minds and hands played important roles in the preparation of this Wao Kele o Puna Comprehensive Management Plan. Likewise, a number of support documents were used in the development of this plan (many are noted as Appendices). As part of the planning process, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs assembled the ‘Aha Kūkā (Advisory Council), bringing members of the diverse Puna community together to provide mana‘o (thoughts and opinions) to OHA regarding the development of this comprehensive management plan (CMP). -

Three Chinese Stores in Early Honolulu

Three Chinese Stores in Early Honolulu Wai-Jane Char Early in the nineteenth century, there were three Chinese stores in Honolulu, listed in The Friend on August 11, 1844 as "Samping [Samsing] & Co., Ahung & Co. [Hungtai], and Tyhune." The stores are long gone and forgotten, but they were significant among the commercial establishments of that time. The first store mentioned, Samsing Co., had a modest beginning in the 1830s, next to a bakery on Fort Street, in the middle of the block near the west entrance of today's Financial Plaza. Later Samsing Co. had a location on King Street facing south in the middle of the block between Bethel and Nuuanu Streets. Yat Loy Co. carried on a dry goods business there for most of the twentieth century.1 The second store mentioned was Hungtai Co., begun even earlier at the northeast corner of Fort and Merchant Streets, where today stands the multi-storied Financial Plaza. In 1838, the store moved to a building called the "Pagoda" on Merchant Street, facing the harbor, between Fort Street and Bethel, then not yet opened as a street.2 The third store, Tyhune, also started before the mid-3os, was at the south- west corner of Hotel and Nuuanu Streets. It was marked merely as "Chinese store" on a map drawn by Alexander Simpson in 1843, during contentions over the land claims of Richard Charlton.3 During the period the Chinese stores were in business, Honolulu changed from a small village into a flourishing town with lumber yards, wharfs, streets, schools, and churches. -

Princess Ka'iulani

MARILYN STASSEN-MCLAUGHLIN Unlucky Star: Princess Ka'iulani PRINCESS KA'IULANI has long been an enigma. The familiar stories of her short life offer little to go on. Published picture books describe the happy child or dutiful teenager or attractive woman, and the oft- told tales become a bit more romanticized with each retelling. It is dif- ficult to see a real Princess Ka'iulani moving through her adolescence in Europe: first, aware of herself as a princess, focused on her educa- tion, trying to please others; then her struggle through sadness and disillusionment; and finally the reluctant and sometimes bitter accep- tance of her fate—a princess with no kingdom to rule. When we peel away the myth, we see Ka'iulani as a young woman forced to face dramatic changes in her short life because of repeated disappointments and thwarted expectations. Through her letters and the observations of others, Ka'iulani becomes a multifaceted woman —a flesh-and-blood person, not a wispy, gauze-like replication. Princess Victoria Kawekiu Ka'iulani Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa Cleghorn, only direct heir by birth to the Hawaiian throne, was born October 16, 1875, to the resounding peal of bells from every church in Honolulu.1 Daughter of Princess Likelike and businessman Archi- bald Scott Cleghorn, she was reared to be royalty. Her mother died when Ka'iulani was only eleven, and the future princess was doted upon by her father, her Uncle David Kalakaua, and numerous rela- tives. She grew up surrounded with the certainty that she could some Marilyn Stassen-McLaughlin is a retired Punahou teacher, tutor, and freelance writer who has had a continuing interest in Princess Ka'iulani and the 'Ainahau Estate for more than twenty years. -

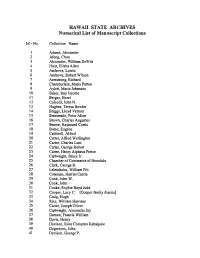

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

Commemorating the Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial

Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial Commemorating the Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th-century in the United States. During this time, several missionary societies were formed. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was organized under Calvinist ecumenical auspices at Bradford, Massachusetts, on the June 29, 1810. The first of the missions of the ABCFM were to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and India, as well as to the Cherokee and Choctaw of the southeast US. In October 1816, the ABCFM established the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, CT, for the instruction of native youth to become missionaries, physicians, surgeons, schoolmasters or interpreters. By 1817, a dozen students, six of them Hawaiians, were training at the Foreign Mission School to become missionaries to teach the Christian faith to people around the world. One of those was ʻŌpūkahaʻia, a young Hawaiian who came to the US in 1809, who was being groomed to be a key figure in a mission to Hawai‘i. ʻŌpūkahaʻia yearned “with great earnestness that he would (return to Hawaiʻi) and preach the Gospel to his poor countrymen.” Unfortunately, ʻŌpūkahaʻia died unexpectedly at Cornwall on February 17, 1818. The life and memoirs of ʻŌpūkahaʻia inspired other missionaries to volunteer to carry his message to the Hawaiian Islands. On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of ABCFM missionaries from the northeast US, set sail on the Thaddeus for the Hawaiian Islands. They first sighted the Islands and arrived at Kawaihae on March 30, 1820, and finally anchored at Kailua-Kona, April 4, 1820. -

Daughters of Hawaiʻi Calabash Cousins

Annual Newsletter 2018 • Volume 41 Issue 1 Daughters of Hawaiʻi Calabash Cousins “...to perpetuate the memory and spirit of old Hawai‘i and of historic facts, and to preserve the nomenclature and correct pronunciation of the Hawaiian language.” The Daughters of Hawaiʻi request the pleasure of Daughters and Calabash Cousins to attend the Annual Meeting on Wednesday, February 21st from 10am until 1:30pm at the Outrigger Canoe Club 10:00 Registration 10:30-11:00 Social 11:00-12:00 Business Meeting 12:00-1:00 Luncheon Buffet 1:00-1:30 Closing Remarks Reservation upon receipt of payment Call (808) 595-6291 or [email protected] RSVP by Feb 16th Cost: $45 Attire: Whites No-Host Bar Eligibility to Vote To vote at the Annual Meeting, a Daughter must be current in her annual dues. The following are three methods for paying dues: 1) By credit card, call (808) 595-6291. 2) By personal check received at 2913 Pali Highway, Honolulu HI 96817-1417 by Feb 15. 3) By cash or check at the Annual Meeting registration (10-10:30am) on February 21. If unable to attend the Annual Meeting, a Daughter may vote via a proxy letter: 1) Identify who will vote on your behalf. If uncertain, you may choose Barbara Nobriga, who serves on the nominating committee and is not seeking office. 2) Designate how you would like your proxy to vote. 3) Sign your letter (typed signature will not be accepted). 4) Your signed letter must be received by February 16, 2017 via post to 2913 Pali Highway, Honolulu HI 96817-1417 or via email to [email protected]. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H.