Judicial Deference and Democratic Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defending and Contesting the Sovereignty of Law: the Public Lawyer As Interpretivist

Defending and contesting the sovereignty of law: the public lawyer as interpretivist Article Accepted Version Lakin, S. (2015) Defending and contesting the sovereignty of law: the public lawyer as interpretivist. Modern Law Review, 78 (3). pp. 549-570. ISSN 0026-7961 doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12128 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/39402/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12128 Publisher: Wiley All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 1 REVIEW ARTICLE Defending and Contesting the Sovereignty of Law: the Public Lawyer as Interpretivist Stuart Lakin* T. R. S. Allan, The Sovereignty of Law Freedom, Constitution and Common Law, Oxford University Press, 2013, 361pp, hb £53.00. How do we determine the content of the law and the constitution in Britain - the legal and constitutional (or conventional) rights, duties and powers of individuals, officials and insti- tutions? On one view, favoured by many UK public lawyers, we simply consult the relevant empiri- cal facts: the rule(s) that identify the sources of law within the constitution, the intentions of parliament in its statutes, the rules of statutory interpretation, the dicta of judges, and the standards of conduct that officials have accepted as binding in their political practices. -

The New Parliamentary Sovereignty

The New Parliamentary Sovereignty Vanessa MacDonnell* Is parliamentary sovereignty still a useful La souverainetiparlementaireest-elle toujours concept in the post-Charter era? Once a un concept utile dans l're postirieure a la central principle of Canadian constitutional Charte? Jadis un principe central du droit law, parliamentarysovereignty has come to be constitutionnel canadien, la souveraineti viewed by many as being of little more than parlementaire est maintenant considere, par historicalinterest. It is perhaps not surprising, plusieurs, comme ayant rien de plus qu'un then, that the doctrine has received relatively intirit historique. Il n'est donc peut-itre pas little scholarly attention since the enactment surprenant que la doctrine a fait l'objet de of the Charter. But while it is undoubtedly relativement peu d'ttention savante depuis true that the more absolute versions of l'doption de la Charte. Mais quoiqu'il soit parliamentary sovereignty did not survive sans aucun doute vrai que les versions les plus the Charter's entrenchment, we should not be absolues de la souveraineteparlementairenont too quick to dismiss the principle's relevance pas survicu & la validation de la Charte, il ne entirely. In thispaperlsuggestthatsomevariant faudrait pas rejeter trop rapidement I'intirit of parliamentary sovereignty continues to du principe tout a fait. Dans cet article, je subsist in Canadian constitutional law. I suggire qu'une variante de la souverainete also suggest that the study of parliamentary parlementaire continue de subsister dans le sovereignty reveals an important connection droit constitutionnel canadien. Mon opinion between the intensity of judicial review and est que l'itude de la souveraineteparlementaire the degree to which Parliamentfocusses on the rivile un lien important entre l'intensite constitutionalissues raisedby a law during the de la revision judiciaire et le degr auquel legislative process. -

The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers

The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers Jared P. Cole Legislative Attorney December 23, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43834 The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers Summary Article III of the Constitution restricts the jurisdiction of federal courts to deciding actual “Cases” and “Controversies.” The Supreme Court has articulated several “justiciability” doctrines emanating from Article III that restrict when federal courts will adjudicate disputes. One justiciability concept is the political question doctrine, according to which federal courts will not adjudicate certain controversies because their resolution is more proper within the political branches. Because of the potential implications for the separation of powers when courts decline to adjudicate certain issues, application of the political question doctrine has sparked controversy. Because there is no precise test for when a court should find a political question, however, understanding exactly when the doctrine applies can be difficult. The doctrine’s origins can be traced to Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison; but its modern application stems from Baker v. Carr, which provides six independent factors that can present political questions. These factors encompass both constitutional and prudential considerations, but the Court has not clearly explained how they are to be applied. Further, commentators have disagreed about the doctrine’s foundation: some see political questions as limited to constitutional grants of authority to a coordinate branch of government, while others see the doctrine as a tool for courts to avoid adjudicating an issue best resolved outside of the judicial branch. Supreme Court case law after Baker fails to resolve the matter. -

Thayerian Deference to Congress and Supreme Court Supermajority Rules

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2003 Thayerian Deference to Congress and Supreme Court Supermajority Rules: Lessons from the Past (Symposium: Congressional Power in the Shadow of the Rehnquist Court: Strategies for the Future) Evan H. Caminker University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/68 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Legislation Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Caminker, Evan H. "Thayerian Deference to Congress and Supreme Court Supermajority Rules: Lessons from the Past (Symposium: Congressional Power in the Shadow of the Rehnquist Court: Strategies for the Future)." Ind. L. J. 78, no. 1 (2003): 73-122. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thayerian Deference to Congress and Supreme Court Supermajority Rule: Lessons from the Pastt EVAN H. CAMINKER* INTRO DUCTION ......................................................................................................... 73 I. THE ATOMISTIC NORM OF DEFERENCE TO CONGRESS ...................................... 79 II. THE HISTORICAL PEDIGREE OF SUPERMAJORITY RULES IN THE FEDERAL AND STATE JUDICIAL SYSTEM S ............................................................................................... 87 III. USING A SUPERMAJORITY PROTOCOL TO ENFORCE THAYERIAN DEFERENCE.... 94 IV. LEARNING SOME LESSONS ABOUT ENFORCING THAYERIAN DEFERENCE ....... 101 A. Assessing the Optimal Strength of Thayerian Deference .......................... -

Judicial Review of Congressional Factfinding

JUDICIAL REVIEW OF CONGRESSIONAL FACTFINDING I. INTRODUCTION Although judicial review still has its challengers,1 their critiques have largely focused on the practice itself. Less prevalent in the litera- ture, although certainly no less of a component of judicial review, is sustained treatment of the measure of deference owed to congressional factfinding.2 That is, where constitutional doctrines are predicated on open, fact-dependent rules of decision, can the Supreme Court, consis- tent with its constitutional authority, independently weigh congres- sional evidence? To the extent that the Court refuses to do so, con- gressional factfinding becomes outcome-determinative. Historically, the Court has given deference to such findings, contenting itself with answering only the procedural question of whether Congress has pre- sented sufficient facts.3 Such deference has recently waned, however, as the Court has increasingly asserted, and broadened, its Cooper v. Aaron4 prerogative to be the supreme expositor of the Constitution.5 Underlying this shift is a desire to ensure that the courts retain final authority to define the meaning of the Constitution by minimizing the outcome-determinative effects of congressional factfinding.6 The Court’s lack of solicitousness to congressional factfinding is in- defensible on both constitutional and prudential grounds; indeed, inso- far as the question of proper deference to Congress is the handmaiden ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1 Compare Bradford R. Clark, Unitary Judicial Review, 72 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 319, 319 (2003) (“[J]udicial review is a unitary doctrine under the Supremacy Clause that requires courts to treat all parts of the Constitution as ‘the supreme Law of the Land’ and to disregard both state and federal law to the contrary.” (citation omitted)), with MARK TUSHNET, TAKING THE CON- STITUTION AWAY FROM THE COURTS (1999) (preferring an iteration of popular constitutional- ism to judicial supremacy in interpreting the Constitution). -

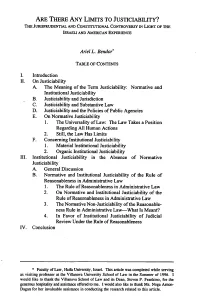

Are There Any Limits to Justiciability? the Jurisprudential and Constitutional Controversy in Light of the Israeli and American Experience

ARE THERE ANY LIMITS TO JUSTICIABILITY? THE JURISPRUDENTIAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL CONTROVERSY IN LIGHT OF THE ISRAELI AND AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Ariel L. Bendor" TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction II. On Justiciability A. The Meaning of the Term Justiciability: Normative and Institutional Justiciability B. Justiciability and Jurisdiction C. Justiciability and Substantive Law D. Justiciability and the Policies of Public Agencies E. On Normative Justiciability 1. The Universality of Law: The Law Takes a Position Regarding All Human Actions 2. Still, the Law Has Limits F. Concerning Institutional Justiciability I. Material Institutional Justiciability 2. Organic Institutional Justiciability III. Institutional Justiciability in the Absence of Normative Justiciability A. General Discussion B. Normative and Institutional Justiciability of the Rule of Reasonableness in Administrative Law 1. The Rule of Reasonableness in Administrative Law 2. On Normative and Institutional Justiciability of the Rule of Reasonableness in Administrative Law 3. The Normative Non-Justiciability of the Reasonable- ness Rule in Administrative Law-What Is Meant? 4. In Favor of Institutional Justiciability of Judicial Review Under the Rule of Reasonableness IV. Conclusion * Faculty of Law, Haifa University, Israel. This article was completed while serving as visiting professor at the Villanova University School of Law in the Summer of 1996. I would like to thank the Villanova School of Law and its Dean, Steven P. Frankino, for the generous hospitality and assistance offered to me. I would also like to thank Ms. Noga Arnon- Dagan for her invaluable assistance in conducting the research related to this article. IND. INT'L & COMP. L. REV. [Vol. 7:2 I. INTRODUCTION Justiciability deals with the boundaries of law and adjudication. -

Individual Rights, Judicial Deference, and Administrative Law Norms in Constitutional Decision Making

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln College of Law, Faculty Publications Law, College of 12-2011 Individual Rights, Judicial Deference, and Administrative Law Norms in Constitutional Decision Making Eric Berger University of Nebraska College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/lawfacpub Berger, Eric, "Individual Rights, Judicial Deference, and Administrative Law Norms in Constitutional Decision Making" (2011). College of Law, Faculty Publications. 165. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/lawfacpub/165 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Law, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Boston University Law Review 91:6 (December 2011), pp. 2029-2102 INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS, JUDICIAL DEFERENCE, AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW NORMS IN CONSTITUTIONAL DECISION MAKING ERIC BERGER* IN TROD UCTION ............................................................................................. 203 1 I. THE COURT'S INCONSISTENT APPROACH TO ADMINISTRATIVE DISCRETION IN INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS CASES ...................................... 2038 A. Deference to Agency Action ...................................................... 2038 1. Deference in Baze v. Rees and the Court's Puzzling Preference for Agency Action ............................................. 2038 2. Deference -

The Interpretation and Construction of Taciturn Bills of Rights

AN ARTICULATE SILENCE: THE INTERPRETATION AND CONSTRUCTION OF TACITURN BILLS OF RIGHTS by JACK TSEN-TA LEE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Birmingham Law School College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. © 2011 Jack Tsen-Ta Lee Jack Tsen-Ta Lee School of Law, Singapore Management University 60 Stamford Road, #04-11, Singapore 178900 Tel +65.6828.1949 y Fax +65.6828.0805 E-mail [email protected] Website http://www.law.smu.edu.sg This dissertation is gratefully dedicated to my PhD supervisor Dr Elizabeth A Wicks, without whose advice and guidance this work would not have come to fruition; and to my parents, Ann and Song Chong Lee, who always believed in me. X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful to the Birmingham Law School and the University of Birmingham for supporting the writing of this dissertation by providing a partial scholarship and an appointment as a visiting lecturer during the 2005–2006 academic year, and a full scholarship in the form of a postgraduate teaching assistantship between September 2006 and August 2008. -

The Rise and Fall of the Separation of Powers

Copyright 2012 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. Northwestern University Law Review Vol. 106, No. 2 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE SEPARATION OF POWERS Steven G. Calabresi, Mark E. Berghausen & Skylar Albertson ABSTRACT—The U.S. Constitution’s separation of powers has its origins in the British idea of the desirability of a Mixed Regime where the King, the Lords, and the Commons all checked and balanced one another as the three great estates of the realm. Aristotle, Polybius, Cicero, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Machiavelli all argued that Mixed Regimes of the One, the Few, and the Many were the best forms of regimes in practice because they led to a system of checks and balances. The Enlightenment killed off the Mixed Regime idea forever because hereditary office-holding by Kings and Lords became anathema. The result was the birth of a functional separation of legislative, executive, and judicial power as an alternative system of checks and balances to the Mixed Regime. For better or worse, however, in the United States, Congress laid claim to powers that the House of Lords and the House of Commons historically had in Britain, the President laid claim to powers the King historically had in Britain, and the Supreme Court has functioned in much the same way as did the Privy Council, the Court of Star Chamber, and the House of Lords. We think these deviations from a pure functional separation of powers are constitutionally problematic in light of the Vesting Clauses of Articles I, II, and III, which confer on Congress, the President, and the courts only the legislative, executive, and judicial power. -

Brief of Administrative and Immigration Law Professors As Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents ______

No. 16-1363 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ____________________ KIRSTJEN M. NIELSEN, SECRETARY OF HOMELAND SECURITY, ET AL., Petitioners, v. MONY PREAP, ET AL., Respondents. ____________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ____________________ BRIEF OF ADMINISTRATIVE AND IMMIGRATION LAW PROFESSORS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ___________________ DEANNA M. RICE ANTON METLITSKY O’MELVENY & MYERS LLP (Counsel of Record) 1625 Eye Street, N.W. [email protected] Washington, D.C. 20006 O’MELVENY & MYERS LLP (202) 383-5300 Times Square Tower Seven Times Square New York, N.Y. 10036 (212) 326-2000 Counsel for Amici Curiae i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether Section 1226(c) imposes mandatory de- tention, without an individualized hearing on flight risk and danger, even when the Department of Homeland Security does not promptly detain an in- dividual when she is released from criminal custody. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .............................. 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................................ 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................. 4 I. THIS COURT HAS NEVER APPLIED CHEVRON IN IMMIGRATION DETENTION CASES .......................................... 6 II. THERE ARE STRONG REASONS NOT TO APPLY CHEVRON DEFERENCE WHEN INTERPRETING THE INA’S DETENTION PROVISIONS ............................... 8 A. The Scope Of Chevron Deference Is Not Unlimited ....................................................... -

The Role of Process in Determining Judicial Deference to the Executive’S National Security Decisions

41112-nyl_21-3 Sheet No. 70 Side A 04/15/2019 13:41:30 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYL\21-3\NYL304.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-APR-19 12:43 THE ROLE OF PROCESS IN DETERMINING JUDICIAL DEFERENCE TO THE EXECUTIVE’S NATIONAL SECURITY DECISIONS Ally Scher* INTRODUCTION .............................................. 767 R I. JUDICIAL REVIEW OF INTRA-EXECUTIVE PROCESS ...... 772 R A. Process as a Marker for Democratic Legitimacy . 773 R B. Enforcing Internal Checks and Balances .......... 776 R II. THE W. BUSH AND OBAMA ADMINISTRATIONS: A FOCUS ON TRANSPARENCY ........................... 779 R A. The W. Bush Administration .................... 780 R B. The Obama Administration ...................... 783 R III. THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION: A HARD LOOK AT INTRA-EXECUTIVE PROCESS .......................... 787 R A. Transgender Military Service Members Ban ...... 788 R B. Travel Ban ..................................... 794 R CONCLUSION................................................ 799 R INTRODUCTION Until recently, courts had a longstanding practice of deeming na- tional security issues to be wholly beyond the judiciary’s role and 41112-nyl_21-3 Sheet No. 70 Side A 04/15/2019 13:41:30 competency.1 This theory of “national security exceptionalism”2 holds that cases involving matters of national security are unique, and conse- quently must be analyzed by courts in a manner different from non- national security cases. In practice, courts dismissed national security cases or deferred to the executive branch without conducting a search- * J.D., 2018, New York University School of Law. Thanks to Lisa Monaco and Zachary Goldman for their helpful feedback throughout the writing process, as well as to Bob Bauer for his insightful comments. Thanks also to the New York University Journal of Legislation & Public Policy staff for their excellent editorial work. -

Keep Calm and Carry On—Judicial Deference to Agency Interpretations

Keep Calm and Carry on—Judicial Deference to Agency Interpretations Evan A. Young and William J. Seidleck* Introduction What was once a comparatively arcane question limited to administrative-law specialists has burst onto the wider legal scheme: when and how must courts defer to agencies’ interpretations of statutes and regulations? The nomination and confirmation of Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, a known and vocal advocate of marginalizing such deference, created a realistic opportunity that the Court might revisit some key administrative-law precedents. The subsequent appointment of Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh enhanced the prospect. The Court’s announcement in December 2018 that it would hear a case for the sole purpose of reconsidering one such doctrine—deference to an agency’s interpretation of its own regulations—removed any doubts that something is brewing, at least for now. Everyone attending the conference for which we have prepared this paper is deeply familiar with Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., probably to the point of having the full citation memorized (it’s in the footnote if not).1 But we start with a very brief refresher so that we will all be on the same page. In Chevron, the Supreme Court announced a standard for courts to use when confronting a statute that a government agency has interpreted. Essentially, the Court articulated a statutory-construction presumption: if the statute is silent or ambiguous about the substantive matter at hand, then courts will presume that Congress intended the agency to fill the gap or prescribe the proper resolution of the ambiguity.2 The first inquiry—often called “Chevron Step One”—is to determine whether a statute is silent or ambiguous in the first place.