Geological Classification the Term 'Anthropocene'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Gssps Render Dual Time-Rock/Time Classification and Nomenclature Redundant?

Do GSSPs render dual time-rock/time classification and nomenclature redundant? Ismael Ferrusquía-Villafranca1 Robert M. Easton2 and Donald E. Owen3 1Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, México, DF, MEX, 45100, e-mail: [email protected] 2Ontario Geological Survey, Precambrian Geoscience Section, 933 Ramsey Lake Road, B7064 Sudbury, Ontario P3E 6B5, e-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Geology, Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas 77710, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Geological Society of London Proposal for “…ending the distinction between the dual stratigraphic terminology of time-rock units (of chronostratigraphy) and geologic time units (of geochronology). The long held, but widely misunderstood distinc- tion between these two essentially parallel time scales has been rendered unnecessary by the adoption of the global stratotype sections and points (GSSP-golden spike) principle in defining intervals of geologic time within rock strata.” Our review of stratigraphic princi- ples, concepts, models and paradigms through history clearly shows that the GSL Proposal is flawed and if adopted will be of disservice to the stratigraphic community. We recommend the continued use of the dual stratigraphic terminology of chronostratigraphy and geochronology for the following reasons: (1) time-rock (chronostratigraphic) and geologic time (geochronologic) units are conceptually different; (2) the subtended time-rock’s unit space between its “golden spiked-marked” -

Assessing the Chronostratigraphic Fidelity of Sedimentary Geological Outcrops in the Pliocene–Pleistocene Red Crag Formation, Eastern England

Downloaded from http://jgs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 27, 2021 Research article Journal of the Geological Society Published online August 14, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2019-056 | Vol. 176 | 2019 | pp. 1154–1168 Where does the time go? Assessing the chronostratigraphic fidelity of sedimentary geological outcrops in the Pliocene–Pleistocene Red Crag Formation, eastern England Neil S. Davies1*, Anthony P. Shillito1 & William J. McMahon2 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, UK 2 Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Princetonlaan 8a, Utrecht 3584 CB, Netherlands NSD, 0000-0002-0910-8283; APS, 0000-0002-4588-1804 * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: It is widely understood that Earth’s stratigraphic record is an incomplete record of time, but the implications that this has for interpreting sedimentary outcrop have received little attention. Here we consider how time is preserved at outcrop using the Neogene–Quaternary Red Crag Formation, England. The Red Crag Formation hosts sedimentological and ichnological proxies that can be used to assess the time taken to accumulate outcrop expressions of strata, as ancient depositional environments fluctuated between states of deposition, erosion and stasis. We use these to estimate how much time is preserved at outcrop scale and find that every outcrop provides only a vanishingly small window onto unanchored weeks to months within the 600–800 kyr of ‘Crag-time’. Much of the apparently missing time may be accounted for by the parts of the formation at subcrop, rather than outcrop: stratigraphic time has not been lost, but is hidden. The time-completeness of the Red Crag Formation at outcrop appears analogous to that recorded in much older rock units, implying that direct comparison between strata of all ages is valid and that perceived stratigraphic incompleteness is an inconsequential barrier to viewing the outcrop sedimentary-stratigraphic record as a truthful chronicle of Earth history. -

Calendrical Calculations: the Millennium Edition Edward M

Errata and Notes for Calendrical Calculations: The Millennium Edition Edward M. Reingold and Nachum Dershowitz Cambridge University Press, 2001 4:45pm, December 7, 2006 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. Unless otherwise indicated, line counts used in describing the errata are positive counting down from the first line of text on the page, excluding the header, and negative counting up from the last line of text on the page including footnote lines. -

“Anthropocene” Epoch: Scientific Decision Or Political Statement?

The “Anthropocene” epoch: Scientific decision or political statement? Stanley C. Finney*, Dept. of Geological Sciences, California Official recognition of the concept would invite State University at Long Beach, Long Beach, California 90277, cross-disciplinary science. And it would encourage a mindset USA; and Lucy E. Edwards**, U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, that will be important not only to fully understand the Virginia 20192, USA transformation now occurring but to take action to control it. … Humans may yet ensure that these early years of the ABSTRACT Anthropocene are a geological glitch and not just a prelude The proposal for the “Anthropocene” epoch as a formal unit of to a far more severe disruption. But the first step is to recognize, the geologic time scale has received extensive attention in scien- as the term Anthropocene invites us to do, that we are tific and public media. However, most articles on the in the driver’s seat. (Nature, 2011, p. 254) Anthropocene misrepresent the nature of the units of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, which is produced by That editorial, as with most articles on the Anthropocene, did the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) and serves as not consider the mission of the International Commission on the basis for the geologic time scale. The stratigraphic record of Stratigraphy (ICS), nor did it present an understanding of the the Anthropocene is minimal, especially with its recently nature of the units of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart proposed beginning in 1945; it is that of a human lifespan, and on which the units of the geologic time scale are based. -

The Climate of the Last Millennium

The Climate of the Last Millennium R.S. Bradley Climate System Research Center, Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, 01003, United States of America K.R. Briffa Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, United Kingdom J.E. Cole Department of Geosciences, University Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, United States of America M.K. Hughes Lab. of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona, 105 W. Stadium, Bldg. 58, Tucson, AZ 85721, United States of America T.J. Osborn Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, United Kingdom 6.1 Introduction records with annual to decadal resolution (or even We are living in unusual times. Twentieth century higher temporal resolution in the case of climate was dominated by near universal warming documentary records, which may include daily with almost all parts of the globe experiencing tem- observations, e.g. Brázdil et al. 1999; Pfister et al. peratures at the end of the century that were signifi- 1999a,b; van Engelen et al. 2001). Other cantly higher than when it began (Figure 6.1) information may be obtained from sources that are (Parker et al. 1994; Jones et al. 1999). However the not continuous in time, and that have less rigorous instrumental data provide only a limited temporal chronological control. Such sources include perspective on present climate. How unusual was geomorphological evidence (e.g. from former lake the last century when placed in the longer-term shorelines and glacier moraines) and macrofossils context of climate in the centuries and millennia that indicate the range of plant or animal species in leading up to the 20th century? Such a perspective the recent past. -

Scientific Dating of Pleistocene Sites: Guidelines for Best Practice Contents

Consultation Draft Scientific Dating of Pleistocene Sites: Guidelines for Best Practice Contents Foreword............................................................................................................................. 3 PART 1 - OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 3 The Quaternary stratigraphical framework ........................................................................ 4 Palaeogeography ........................................................................................................... 6 Fitting the archaeological record into this dynamic landscape .............................................. 6 Shorter-timescale division of the Late Pleistocene .............................................................. 7 2. Scientific Dating methods for the Pleistocene ................................................................. 8 Radiometric methods ..................................................................................................... 8 Trapped Charge Methods................................................................................................ 9 Other scientific dating methods ......................................................................................10 Relative dating methods ................................................................................................10 -

Contents GUT Volume 52 Number 1 January 2003

contents GUT Volume 52 Number 1 January 2003 Journal of the British Society of Gastroenterology, a registered charity ........................................................ AIMS AND SCOPE Leading article Gut publishes high quality original papers on all aspects of 1 Is intestinal metaplasia of the stomach gastroenterology and hepatology as well as topical, authoritative editorials, comprehensive reviews, case reports, reversible? M M Walker Gut: first published as on 1 January 2003. Downloaded from therapy updates and other articles of interest to ........................................................ gastroenterologists and hepatologists. Commentaries EDITOR Professor Robin C Spiller 5s,M,L,XL...T Wang, G Triadafilopoulos 7 HLA-DQ8 as an Ir gene in coeliac disease SPECIAL SECTIONS EDITOR Ian Forgacs K E A Lundin 8 A rat virus visits the clinic: translating basic ASSOCIATE EDITORS discoveries into clinical medicine in the 21st David H Adams Immunofluorescence John C Atherton century C R Boland, A Goel staining of jejunal Ray J Playford ........................................................ Jürgen Scholmerich mucosa from a DQ8+ Jan Tack Clinical @lert AlastairJMWatson coeliac patient. (From the paper by Mazzarella 10 Dyspepsia management in the millennium: to EVIDENCE BASED GASTROENTEROLOGY et al, pp 57–62). test and treat or not? B C Delaney ADVISORY GROUP Richard F A Logan ........................................................ StephenJWEvans Science @lert Andrew Hart Jane Metcalf 12 RUNX 3, apoptosis 0: a new gastric tumour EDITORIAL -

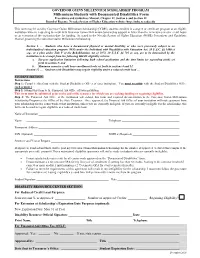

Millennium Students with Documented Disabilities Form

GOVERNOR GUINN MILLENNIUM SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM Millennium Students with Documented Disabilities Form Procedures and Guidelines Manual, Chapter 12, Section 6 and Section 12 Board of Regents, Nevada System of Higher Education website: http://nshe.nevada.edu This form may be used by Governor Guinn Millennium Scholarship (GGMS) students enrolled in a degree or certificate program at an eligible institution who are requesting to enroll with Governor Guinn Millennium Scholarship support in fewer than the minimum semester credit hours or an extension of the expiration date for funding. As stated in the Nevada System of Higher Education (NSHE) Procedures and Guidelines Manual governing the Governor Guinn Millennium Scholarship: Section 6 … Students who have a documented physical or mental disability or who were previously subject to an individualized education program (IEP) under the Individual with Disabilities with Education Act, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1400 et seq., or a plan under Title V of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. §§ 791 et. seq. are to be determined by the institution to be exempt from the following GGMS eligibility criteria: a. Six-year application limitation following high school graduation and the time limits for expending funds set forth in section 5; and b. Minimum semester credit hour enrollment levels set forth in sections 4 and 11. Section 12 … Students with Disabilities may regain eligibility under a reduced credit load … STUDENT SECTION: Instructions Step 1: Complete this form with the Student Disabilities Officer of your institution. You must recertify with the Student Disabilities Office each semester. Step 2: Submit this form to the Financial Aid Office of your institution. -

Some False Beliefs Concerning the End Times

Some False Beliefs Concerning the End Times It has been said: “Wherever God builds a church, the devil sets up a chapel next door.” In other words, whenever God’s saving truth is proclaimed, the devil will follow close behind to spin false teachings that are intended to rob people of their salvation. This certainly has been true with the Bible’s teaching of the end times. Many Christian teachers claim that there will be a semi-utopian thousand-year period of prosperity and blessing on earth immediately after the New Testament era and immediately prior to the final judgment. This thousand-year period is called the millennium (from the Latin language in which mille means “thousand” and annus means “year”). The following time line shows how the millennialists view the end times. Compare this with the scriptural time line below it. Millennialism: Scripture: The thousand years The idea of a millennium comes from Revelation chapter 20. It is important to note that this is the only passage in the entire Bible which mentions a thousand-year period. Revelation 20:1-3,7-12: I saw an angel coming down out of heaven, having the key to the Abyss and holding in His hand a great chain. He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil, or Satan, and bound him for a thousand years. He threw him into the Abyss, and locked and sealed it over him, to keep him from deceiving the nations anymore until the thousand years were ended. When the thousand years are over, Satan will be released from his prison and will go out to deceive the nations in the four corners of the earth—Gog and Magog—to gather them for battle. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Formal Ratification of the Subdivision of the Holocene Series/ Epoch

Article 1 by Mike Walker1*, Martin J. Head 2, Max Berkelhammer3, Svante Björck4, Hai Cheng5, Les Cwynar6, David Fisher7, Vasilios Gkinis8, Antony Long9, John Lowe10, Rewi Newnham11, Sune Olander Rasmussen8, and Harvey Weiss12 Formal ratification of the subdivision of the Holocene Series/ Epoch (Quaternary System/Period): two new Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSPs) and three new stages/ subseries 1 School of Archaeology, History and Anthropology, Trinity Saint David, University of Wales, Lampeter, Wales SA48 7EJ, UK; Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, Wales SY23 3DB, UK; *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Brock University, 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way, St. Catharines, Ontario LS2 3A1, Canada 3 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois 60607, USA 4 GeoBiosphere Science Centre, Quaternary Sciences, Lund University, Sölveg 12, SE-22362, Lund, Sweden 5 Institute of Global Change, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xian, Shaanxi 710049, China; Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minne- sota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA 6 Department of Biology, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick E3B 5A3, Canada 7 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa K1N 615, Canada 8 Centre for Ice and Climate, The Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Julian Maries Vej 30, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark 9 Department of Geography, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 10 -

End Times Timeline CCC August 30, 2020 Visuals

End Times Timeline CCC August 30, 2020 Visuals – Across the stage signage. Four signs representing each age. Three cutouts – One of Rapture, one of Second Coming, one of Zombie Introduction – Quick show of hands. How many people have ever found end times stuff to be Confusing? If your neighbor just raised his/her hand, say to them “I knew you were confused.” How would you like to have a quick handle on what is going to happen when Jesus comes back again? Today, I am going to try to make that happen in under 40 minutes. So lets pray. Seriously… Pray OK, so the end times are so crazy partly because of terminology. Partly because of theological positions. Partly because the Bible is crystal clear on some things – like Jesus is coming back. Unclear on other things – like what is the order of events. And downright intentionally obtuse about other things – like when the rapture will take place. So I am going to run after this with a really clear statement up front. “I might be wrong.” I know… a shocking thing for a pastor to admit. Now raise your eyebrows and turn to the person next to you and say – he might be wrong. (really, I wont do that all message). I have studied this for 30 years now and changed my mind a few times. I may change it again in five years. I may have never been right on some aspects – so I’ll do my best to share multiple views and my personal opinion… but just so you know that I know that this is complex stuff that will come down in the future – and I am approaching it all with humility – and I’ll let you know if I change my mind.