A Primer on U.S. Intellectual Property Rights Applicable to Music Information Retrieval Systems Michael W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: an Empirical Analysis of Music in Film

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: An Empirical Analysis of Music in Film Jon Gillick David Bamman School of Information School of Information University of California, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (Guha et al., 2015; Kociskˇ y` et al., 2017), natural language understanding (Frermann et al., 2017), Soundtracks play an important role in carry- ing the story of a film. In this work, we col- summarization (Gorinski and Lapata, 2015) and lect a corpus of movies and television shows image captioning (Zhu et al., 2015; Rohrbach matched with subtitles and soundtracks and et al., 2015, 2017; Tapaswi et al., 2015), the analyze the relationship between story, song, modalities examined are almost exclusively lim- and audience reception. We look at the con- ited to text and image. In this work, we present tent of a film through the lens of its latent top- a new perspective on multimodal storytelling by ics and at the content of a song through de- focusing on a so-far neglected aspect of narrative: scriptors of its musical attributes. In two ex- the role of music. periments, we find first that individual topics are strongly associated with musical attributes, We focus specifically on the ways in which 1 and second, that musical attributes of sound- soundtracks contribute to films, presenting a first tracks are predictive of film ratings, even after look from a computational modeling perspective controlling for topic and genre. into soundtracks as storytelling devices. By devel- oping models that connect films with musical pa- 1 Introduction rameters of soundtracks, we can gain insight into The medium of film is often taken to be a canon- musical choices both past and future. -

Stargate Sg1 "Flesh and Blood" Episode #1001 Dialogue Continuity Script

STARGATE SG1 "FLESH AND BLOOD" EPISODE #1001 DIALOGUE CONTINUITY SCRIPT June 5, 2006 Prepared by: Line 21 Media Services Ltd. #122 - 1058 Mainland Street Vancouver, B.C. V6B 2T4 Phone: (604) 662-4600 [email protected] 1 STARGATE SG-1 - "Flesh and Blood" - Episode #1001 TIMECODE DIALOGUE START TIMECODE 01:00:00:00 AT FIRST FRAME OF PICTURE RECAP 01:00:00:05 TEAL'C: Previously on Stargate SG-1... 01:00:03:08 DOCI: In the name of the gods, ships shall be built to carry our warriors out amongst the stars. 01:00:08:22 ORLIN: Everything Origins followers devote themselves to is a lie. 01:00:12:16 MITCHELL: Whose baby is it? 01:00:13:21 VALA: I don't know. 01:00:14:19 PRIOR (V/O):The child is the will of the Ori. 01:00:18:10 VALA (V/O): The ships are planning to leave. 01:00:19:28 VALA (CONT'D): Somewhere out there, the Ori have a working supergate. 01:00:22:11 CARTER (V/O): We've managed to locate the dialing control crystals on one particular section of the gate. 2 STARGATE SG-1 - "Flesh and Blood" - Episode #1001 01:00:26:10 CARTER (CONT'D): We dial out before they can dial in. 01:00:28:20 CARTER (CONT'D INTO RADIO): Something's happening. 01:00:31:09 (EXPLOSION) 01:00:35:19 CARTER (CONT'D): My god... 01:00:36:27 NETAN: I didn't think you were that stupid. 01:00:38:14 TEAL'C: I have come to seek the assistance of the Lucian Alliance. -

Inside Tv Pg 7 01-03

The Goodland Daily News / Friday, January 3, 2003 7 Channel guide Legal Notice Prime time 2 PBS; 3 TBS; 4 ABC; 5 HBO; 6 CNN; 7 CBS; 8 NBC (KS); 11 TVLND; 12 Pursuant to K.S.A. 82a-1030, the board of directors of ESPN; 13 FOX; 15 MAX; 16 TNN; 18 the Northwest Kansas Ground water Management LIFE; 20 USA; 21 SHOW; 22 TMC; 23 Mammograms can District No. 4 will conduct on February 19, 2003 a TV MTV; 24 DISC; 27 VH1; 28 TNT; 30 public hearing in order to hear testimony regarding FSN; 31 CMT; 32 FAM; 33 NBC (CO); save your life. 34 NICK; 36 A&E; 38 SCI; 39 TLC; 40 If you are between 50-64 revisions to the 2003 operating budget. Said revisions FX; 45 FMC; 49 E!; 51 TRAV; 53 WB; you may qualify for a FREE consist of incorporating all 2002 unexpended funds 54 ESPN2; 55 ESPN News; 58 HIST; mammogram. into the previously approved 2003 operating budget. schedule 62 HGTV; 99 WGN. The hearing will begin at 11:30 a.m. central standard For more information time at the Comfort Inn, 2225 S. Range, Colby, Kan- regarding this program Friday Evening January 3, 2003 contact: sas. Copies of the proposed revised 2003 budget will 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KLBY/ABC Tostitos Fiesta Bowl Local Local Local Dorendo Harrel be made available at the hearing site. Attest: Robin Deeds, GMD 4 Secretary KBSL/CBS Hack 48 Hours Local Late Show Late Late Show Local (785) 899-4888 KSNW/NBC Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Conan Local KUSA/NBC Dateline NBC Law & Order: SVU Local Tonight Show Conan KDVR/FOX The Nutty Professor Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E No Mercy Third Watch Biography No Mercy AMC Smokey and the Bandit II Tales from Empire of the Ants Tales from CMT Living Proof: The Hank Williams, Jr. -

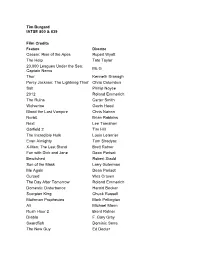

Tim Burgard IATSE 800 & 839 Film Credits Caesar: Rise of the Apes

Tim Burgard IATSE 800 & 839 Film Credits Feature Director Caesar: Rise of the Apes Rupert Wyatt The Help Tate Taylor 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: Mc G Captain Nemo Thor Kenneth Branagh Percy Jackson: The Lightning Thief Chris Columbus Salt Phillip Noyce 2012 Roland Emmerich The Ruins Carter Smith Wolverine Gavin Hood Blood the Last Vampire Chris Nahon Norbit Brian Robbins Next Lee Tamahori Garfield 2 Tim Hill The Incredible Hulk Louis Leterrier Evan Almighty Tom Shadyac X-Men: The Last Stand Brett Ratner Fun with Dick and Jane Dean Parisot Bewitched Robert Stadd Son of the Mask Larry Guterman Me Again Dean Parisot Cursed Wes Craven The Day After Tomorrow Roland Emmerich Domestic Disturbance Harold Becker Scorpion King Chuck Russell Mothman Prophecies Mark Pellington Ali Michael Mann Rush Hour 2 Brent Ratner Diablo F. Gary Gray Swordfish Dominic Sena The New Guy Ed Decter Pluto Nash Ron Underwood Down and Under David McNally The Patriot Roland Emmerich The Red Planet Anthony Hoffman Mission to Mars Brian dePalma Dungeons & Dragons Cory Solomon Stuart Little Rob Minkoff Inspector Gadget David Kellogg Small Soldiers Joe Dante Supernova Walter Hill 20 Billion Michael Tolkin Mighty Joe Young Ron Underwood Superman Returns John Sheehy Virus John Bruno Batman and Robin Joel Schumacher Chain Reaction Andrew Davis Mars Attacks! Tim Burton The Borrowers Michael McAlister The Phantom Joe Dante Jumanji Joe Johnston Tank Girl Rachel Talalay Cutthroat Island Renny Harlin Terminal Velocity Deran Sarafian Holy Matrimony Leonard Nimoy Stargate Roland -

CTPR-441 Sound Design August 15,2019 Units: 2 Fall 2018 - Thursday - 1:00 - 3:50PM Location: SPS 115

CTPR-441 sound design August 15,2019 Units: 2 Fall 2018 - Thursday - 1:00 - 3:50PM Location: SPS 115 Instructor: Stephen Flick SA: Audrey Gu Office: SCA 444 Office Hours: By Appointment Sound Department 213-740-7700 Course Description Exploration of the techniques and processes for creating sounds that don’t exist. Learning Objectives To establish an understanding of the processes and techniques used to create “sounds never heard before.” Sound Design has the most expressive and creative opportunities and challenges in Genre Films; particularly Science Fiction, Fantasy, Horror, and Action/Thrillers. Students will be exposed to the historical, theoretical, and practical aspects of sound design for these genres. Students will be challenged to analyze, design, record and present new concepts and sounds as well as constructively critique. Exercises will include audio-only constructions/montages as well as to existing synchronous images. This class will specifically cover Creatures and their Worlds, historical, futuristic, magical, organic, inorganic, and mechanical. By the completion of this class students will have developed strategies and skills to deal with new and different challenges in genre sound design Prerequisite(s): CTPR-310 Intermediate Production or CTPR-508 Production II Description and Assessment of Assignments Assignments will be to create voices from creature video clips, which will include vocal elements, character movement, and interaction with scenic elements. Assignments will also Include audio-only pieces. The work will be done and reviewed in Avid Protools. Assume that there will be quizzes each week covering the material from the previous lectures and assignments. This is to encourage attendance and retention. -

STARGATE by Dean Devlin & Roland Emmerich Devlin/Emmerich Draft 7

STARGATE by Dean Devlin & Roland Emmerich Devlin/Emmerich Draft 7/6/93 FADE IN: PRIMITIVE SKETCHES E.C.U. Etched on stone, a JACKAL. Another of a GAZELLE, a spear piercing its skin. Primitive, yet dramatic tribal etchings. The SOUND of ancient CHANTING is HEARD. Widen to REVEAL... 1 EXT. DESERT LANDSCAPE, NORTH AFRICA - SUNSET 1 A young BOY chisels his artwork into the stone ROCKFACE at the edge of this valley. An old MEDICINE MAN, his face painted with bizarre white stripes, CHANTS nearby. The boy abruptly stops his work at the SOUND of distant CRIES. Quickly he climbs the stone. Standing at the top he SEES... HUNTERS 2 RETURNING FROM A KILL. THEY MARCH TOWARDS A SMALL CAMPSITE. 2 The tribes people rushing to greet them. Super up: North Africa 8000 B.C. 3 OMITTED 3 4 A BLAZING FIRE - LATER THAT NIGHT 4 Silhouetted tribesmen dancing in bizarre animal MASKS. Feet STOMPING. The young Boy stares at the fire, SPARKS rising into the air. We PAN UP following the sparks into the sky. A full moon. A SHADOW is suddenly cast across the moon, blotting it out. 5 INT. TENT - LATER THAT NIGHT 5 The young Boy sleeps. Above him hangs an odd carving that slowly begins to RATTLE. The tent's fabric begins to FLAP. The Boy's eyes pop open. He HEARS the sounds of a quickly brewing storm. Footsteps. People hurrying, calling out to each other. Suddenly the tent's entrance flap SAILS OPEN. BRIGHT LIGHT pours in through the entrance. 6 EXT. CAMPSITE - NIGHT 6 The Boy exits his tent, staring at the light, intrigued. -

Stargate Atlantis Allegiance (Legacy Book 3) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STARGATE ATLANTIS ALLEGIANCE (LEGACY BOOK 3) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Melissa Scott | 296 pages | 17 Jun 2020 | FANDEMONIUM BOOKS | 9781905586561 | English | none STARGATE ATLANTIS Allegiance (Legacy book 3) PDF Book Skip to main content. It has brought us together. Among these thieves and rogues is Vala Mal Doran, on the trail of the fabulous treasure left behind by the System Lord Kali. Artok : I am not. But life never stays simple for long…. John Sheppard submits his resignation following a mission in which two of his team members were lost while Elizabeth Weir negotiates with two warring tribes who have traces of the Ancient ATA gene. The expedition reestablishes contact with their Pegasus allies and learns that the Wraith are being united under a single Wraith Queen called Death. Namespaces Article Talk. Inheritors Book 6 in the Legacy Series. Please contact us if any details are missing and where possible we will add the information to our listing. And I don't mean the end of the Goa'uld. Chief Ladon Radim turns to Atlantis for help when the Genii's first starship disappears -- before time runs out for her crew. Payment details. Season 5. Missing Information? Artok : I asked a question of this Tok'ra. He reveals that he was left for dead in the forest but his symbiote managed to sustain him. The Third Path. Book search. Refer to eBay Return policy for more details. Julie Fortune. Email to friends Share on Facebook - opens in a new window or tab Share on Twitter - opens in a new window or tab Share on Pinterest - opens in a new window or tab. -

Stargate TCG: SG-1 Checklist Card Name Card Type Rarity Number

Stargate TCG: SG-1 Checklist Card Name Card Type Rarity Number Anubis, Banished Lord Adversary Decks 1 Anubis, Galactic Menace Adversary Rare 2 Apophis, Enemy Reborn Adversary Rare 3 Apophis, Threat to Earth Adversary Decks 4 Ardent Prior, Damaris Adversary Rare 5 Baal, Charming Villain Adversary Rare 6 Caulder, Administrator Adversary Uncommon 7 Devout Prior, Instrument of the Ori Adversary Common 8 Fifth, Hardened Foe Adversary Uncommon 9 Frank Simmons, Government Adversary Adversary Uncommon 10 Hathor, Mother of All Pharaohs Adversary Rare 11 Imhotep, Enemy Within Adversary Uncommon 12 Ja'din, Servant of Cronus Adversary Common 13 Klorel, Mighty Warrior Adversary Uncommon 14 Mollem, Duplicitous Diplomat Adversary Rare 15 Mot, Servant of Baal Adversary Rare 16 Nirrti, Goddess of Darkness Adversary Uncommon 17 Osiris, Emissary of Anubis Adversary Rare 18 Replicator Carter, Leader of the Scourge Adversary Rare 19 Robert Kinsey, Ambitious Senator Adversary Common 20 Samuels, Turncoat Adversary Uncommon 21 Shak'l, Servant of Apophis Adversary Common 22 Sokar, Rising Nemesis Adversary Rare 23 Tanith, Lurker Adversary Uncommon 24 Trofsky, Hathor's Lieutenant Adversary Uncommon 25 Yu, The Great Adversary Common 26 Anise, Determined Archaeologist Character Common 27 Aris Boch, Bounty Hunter Character Common 28 Artok, Impassioned Rebel Character Common 29 Bauer, NID Patsy Character Uncommon 30 Bill Lee, Engineering Specialist Character Common 31 Burke, C.I.A. Operative Character Rare 32 Chaka, Tribal Leader Character Common 33 Chekov, Russian -

Detecting and Correcting Typing Errors in Open-Domain Knowledge Graphs Using Semantic Representation of Entities

Detecting and correcting typing errors in open-domain knowledge graphs using semantic representation of entities by Daniel Dur~aesCaminhas A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Computing Science University of Alberta c Daniel Dur~aesCaminhas, 2019 Abstract Large and accurate Knowledge Graphs (KGs) are often used as a source of structured knowledge in many natural language processing (NLP) tasks, in- cluding question-answering systems, conversational agents, information inte- gration, named entity recognition, document ranking, among others. Various approaches for creating and updating KGs exist, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Manually curated KGs can be very accurate, but require too much effort and tend to be small and domain-specific. Larger cross-domain KGs can be created automatically from unstructured or semi- structured data, but even the best methods today are error-prone. Given this trade-off between completeness and correctness, researchers have been attempting to refine KGs after they have been constructed, by adding missing knowledge or finding and correcting erroneous information. This thesis proposes a fully automatic method for detecting and correcting type assignments in an open-domain KG, provided that the entities in the KG are mentioned in a text corpus. Our approach consists of creating semantic representations (embeddings) of the entities in the KG that take into account how they are mentioned in the corpus and their properties in the KG itself, and using these embeddings as features for machine learning classifiers which are trained to distinguish entities of each type. To test our solution, we use DBpedia as the KG and Wikipedia as the text corpus, and we perform an extensive retrospective evaluation in which almost 15,000 entity-type pairs were verified by humans. -

Level-3-Stargate-Penguin-Readers.Pdf

The mysterious StarGate is 10,000 years old. When a group of soldiers go through it they travel millions of miles to a world where they have to fight to stay alive. Will they live? Will they find a way to get back to Earth? Or will they die? Penguin Readers are simplified texts designed in association with Longman, the wo rld famous educational publisher. to prov ide a step-by-step approach to the joys of reading for pleasure. Each book has an introductio n and extensive act ivity material. They are published at seve n levels from Easystarts (200 words) to Advanced (3000 wo rds). Ser ies Edito rs: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter NEW EDITON 6 Advanced (3000 words) Contemporary 5 Upper Intermediate (2300 words) C lassics 4 Intermediate (1700 wo rds) • O riginals 3 Pre-lnrermediate (1200 words) tJ 2 Elementar y (600 words) IBeginner (300 words) Br itish English Easysta rts (200 words) American English www.penguinreaders.com s TA R G AT E " jva~us F1L\!"l \ <ToJ<N ~ n> I~ ROI."'~ D ~loo) K~,j,\R .."",,,,If ffiDIO (JL\')J ' I~ CAR0I.CO Plffi'RE.S lmllll (11.11£001 JAYEDAVlDSO, ~ :HI.E I S Ell -~ IJ.QIJ.; CO;.< \TRl'CTl o sm mTRL~Sfl . NIE.\IPAD ER ·ST.\RGAn' 'r1I1C\ In.1Jf{)R5 -':lH\1DAR."lJ1lJ ...... ,ltREKB :\EOl J~ '"l'.:~arT'rnT ~'!#rn~TRI n nTO f'Oll OS ,c::)OSEf'H PORRO '"l ~ l: CH. illJ_ DL11lJh.. -=lUGERGRIm ~ --J:': I:.w. \nLrn. L':'; Il£.'i [),tJ a ~\ 'l\ = ~I!tR.l O K.>"\ m . -

Atlantic News Photos by Scott E

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 28 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 4C | ATLANTIC NEWS | NOVEMBER 18, 2005 | VOL 31, NO 46 SEACOAST ENTERTAINMENT &ARTS | ATLANTICNEWS.COM . 26,000 COPIES WEEKLY | 22,671 MAILED TO 15 TOWNS | TO ADVERTISE, CALL (603) 926-4557 TODAY! DAYS TLANTIC LASSIFIEDS WORDS A C 30 BUCKS HOLIDAY HOLLY DAY FAIR AT OLMM HAMPTON | The Catholic Women’s 11/19/05 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 Club of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal WBZ-4 (3:30) College Football Alabama at Auburn. Entertainment Without a Trace CSI: Miami “Recoil” 48 Hours Mystery ’ News (:35) The (12:05) Da Vinci’s In- (CBS) (Live) (HD) (CC) Tonight (N) ’ (CC) “Light Years” (CC) (iTV) ’ (HD) (CC) (CC) Insider quest (Part 2 of 2) Church will present their annual Holly Day WCVB-5 (4:30) PGA Golf WGC World Cup -- Third Patriots All-Access ››› Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002, Fantasy) News (:35) 24 “7:00AM - Enter- Fair on Saturday, November 19 from 9 a.m. (ABC) Day. From Algarve, Portugal. (CC) (HD) Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint. ’ (CC) (CC) 8:00AM” ’ (CC) prise to 2:30 p.m. -

100 Piano Classics

100 Piano Classics: In The The Best Of The Red Army Lounge Choir Samuel Joseph Red Army Choir SILCD1427 | 738572142728 SILKD6034 | 738572603427 CD | Lounge Album | Russian Military Songs Samuel Joseph is 'The Pianists' Pianist'. Born in Hobart, Re-mastered from the original session tapes, the recordings Tasmania he grew up performing at restaurants, events and for this 2CD set were all made in Moscow over a number of competitions around the city before settling in London in years. They present the most complete and definitive 2005. He has brought his unique keyboard artistry to many collection of recordings of military and revolutionary songs celebrated London venues including the Dorchester, the by this most versatile of choirs. Includes Kalinka, My Savoy, Claridges, the Waldorf and Le Caprice. He has Country, Moscow Nights, The Cossacks, Song of the Volga entertained celebrities as diverse as Bono to Dustin Boatmen, Dark Eyes and the USSR National Anthem. Hoffman along with heads of state and royalty. Flair, vibrancy and impeccable presentation underline his keyboard skills. This 100 track collection highlights his astounding repertoire Swinging Mademoiselles - Captain Scarlet Groovy French Sounds From Barry Gray The 60s FILMCD607 | 738572060725 Various Artists CD | TV Soundtracks SILCD1191 | 738572119126 CD | French Long before England started swinging in the mid-1960s, Barry Gray's superlative music to Gerry Anderson's first France was the bastion for cool European pop sounds. project post Thunderbirds. Never before available, these Sultry young French maidens, heavy on mascara and a recordings have been carefully restored and edited from languid innocence cast a sexy spell with what became composer Barry Gray's own archive courtesy of The Barry known as 'les annees ye ye'.