Economic Openness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

AR-15-16 with Cover.Pmd

Annual Report 2015-16 (April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016) OF CHEM E IC T A U L T I E T N S G N I I N E N E A I R D S N I E STD. 1947 Indian Institute of Chemical Engineers 1 List of Council Members for 2015 & 2016 2015 Designation 2016 Mr G V Sethuraman, Director, Enfab Industries Pvt. Ltd., C-2, Shantiniwas, Mettuguda, Mr Shyam Bang, Executive Director, Jubilant Life Sciences Ltd., 1A, Sector 16A, Noida Secunderabad – 500 017, Andhra Pradesh, [O] (040) 2782-4343, 2782-0010/2782-3073, President - 201 301, Uttar Pradesh, [R] (011) 2922-9999, [Mobile] (0)9810106660, [R] (040) 2733-4321/5363, [Mobile] 9849028854, [email protected] [email protected] Prof Ch V Ramachandra Murthy, Department of Chemical Engineering, Andhra Univer- Immediate Past Mr G V Sethuraman, Enfab Industries Pvt. Ltd., Plot No. 138-A, IDA Mallapur, Hyderabad sity, Waltair, Visakhapatnam 530 003, [O] (0891) 2754871 Extn.496, [R] (0891) 2504520, President 500 076, Andhra Pradesh, O] (040) 2782-4343, 2782-0010/2782-3073, [R] (040) 2733- [Mobile] (0)94403 89136, [email protected] 4321/5363, [Mobile] 9849028854, [email protected] Mr D M Butala, 5, Mohak, B/h. Manisha Society, Behind Raja’s Lavkush, Bunglow, Near Prof S V Satyanarayana, Department of Chemical Engineering, JNTUA College of Upendra Bhatt’s Bunglow, Syed Vasana Road, Baroda 390 015, [R] (0265) 225-3977, Engineering, Anantapuramu Dist., Andhra Pradesh – 515002, [O] (08554) 272325 Ext: [Mobile] (0)9979853514, [email protected] Vice 4602, [Mobile] (0)9849509167, [email protected] Presidents Prof V V Basava Rao, Plot No; 184, Tirumala Nagar Colony, Meerpet (V), Moula-Ali Hous- Prof G A Shareef, 9, 2nd Stage, 2 Block, R M V Extn. -

Management Accountant

7+(0$1$*(0(17 THE MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANT ACCOUNTANT THE MANAGEMENT SEPTEMBER 2016 9 51 NO. VOL. 7+(-2851$/)25&0$V $&&2817$17 ,661 6HSWHPEHU92/123DJHV ÃÌÊ «iÌÌÛiiÃÃ ` 100 «iÝÌÞÊÌÊ v`iVi 7+(,167,787(2)&267$&&2817$1762),1',$ 6WDWXWRU\ERG\XQGHUDQ$FWRI3DUOLDPHQW ZZZLFPDLLQ www.icmai.in September 2016 The Management Accountant 1 2 The Management Accountant September 22016 www.icmai.in The Institute of Cost Accountants of India PRESIDENT THE INSTITUTE OF COST ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA CMA Manas Kumar Thakur (erstwhile The Institute of Cost and Works Accountants [email protected] of India) was first established in 1944 as a registered VICE PRESIDENT CMA Sanjay Gupta company under the Companies Act with the objects of [email protected] promoting, regulating and developing the profession of COUNCIL MEMBERS Cost Accountancy. CMA Amit Anand Apte, CMA Ashok Bhagawandas Nawal, On 28 May 1959, the Institute was established by a CMA Avijit Goswami, CMA Balwinder Singh, special Act of Parliament, namely, the Cost and Works CMA Biswarup Basu, CMA H. Padmanabhan, Accountants Act 1959 as a statutory professional body for CMA Dr. I. Ashok, CMA Niranjan Mishra, CMA Papa Rao Sunkara, CMA P. Raju Iyer, the regulation of the profession of cost and management CMA Dr. P V S Jagan Mohan Rao, accountancy. CMA P. V. Bhattad, CMA Vijender Sharma It has since been continuously contributing to the Shri Ajai Das Mehrotra, Shri K.V.R. Murthy, growth of the industrial and economic climate of the Shri Praveer Kumar, Shri Surender Kumar, country. Shri Sushil Behl The Institute of Cost Accountants of India is the only Secretary recognised statutory professional organisation and CMA Kaushik Banerjee, [email protected] licensing body in India specialising exclusively in Cost Sr. -

Magazine Can Be Printed in Whole Or Part Without the Written Permission of the Publisher

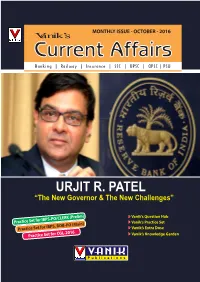

MONTHLY ISSUE - OCTOBER - 2016 CurrVanik’s ent Affairs Banking | Railway | Insurance | SSC | UPSC | OPSC | PSU URJIT R. PATEL “The New Governor & The New Challenges” Vanik’s Question Hub -PO/CLERK (Prelim) Practice Set for IBPS Vanik’s Practice Set -PO (Main) Practice Set for IBPS, BOB Vanik’s Extra Dose GL-2016 Practice Set for C Vanik’s Knowledge Garden P u b l i c a t i o n s VANIK'S PAGE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORTS OF INDIA NAME OF THE AIRPORT CITY STATE Rajiv Gandhi International Airport Hyderabad Telangana Sri Guru Ram Dass Jee International Airport Amristar Punjab Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport Guwaha ti Assam Biju Patnaik International Airport Bhubaneshwar Odisha Gaya Airport Gaya Bihar Indira Gandhi International Airport New Delhi Delhi Andaman and Nicobar Veer Savarkar International Airport Port Blair Islands Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport Ahmedabad Gujarat Kempegowda International Airport Bengaluru Karnatak a Mangalore Airport Mangalore Karnatak a Cochin International Airport Kochi Kerala Calicut International Airport Kozhikode Kerala Trivandrum International Airport Thiruvananthapuram Kerala Raja Bhoj Airport Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Devi Ahilyabai Holkar Airport Indore Madhya Pradesh Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport Mumbai Maharashtr a Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport Nagpur Maharashtr a Pune Airport Pune Maharashtra Zaruki International Airport Shillong Meghalay a Jaipur International Airport Jaipur Rajasthan Chennai International Airport Chennai Tamil Nadu Civil Aerodrome Coimbator e Tamil Nadu Tiruchirapalli International Airport Tiruchirappalli Tamil Nadu Chaudhary Charan Singh Airport Lucknow Uttar Pradesh Lal Bahadur Shastri International Airport Varanasi Uttar Pradesh Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose International Airport Kolkata West Bengal Message from Director Vanik Publications EDITOR Dear Students, Mr. -

Reforming Soes in Asia: Lessons from Competition Law and Policy in India

ADBI Working Paper Series REFORMING SOES IN ASIA: LESSONS FROM COMPETITION LAW AND POLICY IN INDIA Vijay Kumar Singh No. 1056 December 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute Vijay Kumar Singh is a professor and head of the Department of Law and Management at the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies School of Law in Dehradun, India. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Singh, V. K. 2019. Reforming SOEs in Asia: Lessons from Competition Law and Policy in India. ADBI Working Paper 1056. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/reforming-soes-asia-lessons-competition-law-policy-india Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building, 8th Floor 3-2-5 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan Tel: +81-3-3593-5500 Fax: +81-3-3593-5571 URL: www.adbi.org E-mail: [email protected] © 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute ADBI Working Paper 1056 V. -

Doing Business in India: What Has Liberalization Changed?

CENTER FOR RESEARCH ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND POLICY REFORM Working Paper No. 93 Doing Business in India: What has liberalization changed? by Naushad Forbes * February 2001 Stanford University John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Building 366 Galvez Street | Stanford, CA | 94305-6015 * Naushad Forbes is Consulting Professor, Department of Industrial Engineering, Stanford University and Director, Forbes Marshall, India. Doing Business in India: What has liberalization changed? Naushad Forbes Paper presented at the Center for Research on Economic Development and Policy Reform Conference on Indian Economic Prospects: Advancing Policy Reform Abstract The Indian economic reforms that began in 1991 have unleashed progressive forces in the Indian economy in the past decade. During the economic boom of 1991-96, domestic and foreign private investment surged, without significantly altering the structure and operation of existing Indian firms. The ensuing slowdown during 1996-99 revealed the internal weaknesses of Indian industry and started to drive changes. The evolving relationship between Indian and foreign firms reflects the changes ushered in by the reforms. This paper suggests two relatively neglected areas of pending reform: the need for reform to perculate to the local level and the need to build a public lobby for reform. Because technology lies at the heart of international competitiveness, this paper then reviews technology and innovation in the periods before and after 1991. Before 1991, the tremendous investment in R&D, with its heavy emphasis on indigenisation, failed to enhance the efficiency and productivity of Indian industry. The pressure brought by the liberalization of 1991-99 spurred fundamental changes in technology and innovation, especially at the micro-level. -

The-Hindu-Special-Diary-Complete

THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 2 DIARY OF EVENTS 2015 THE HINDU THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 panel headed by former CJI R. M. Feb. 10: The Aam Aadmi Party NATIONAL Lodha to decide penalty. sweeps to power with 67 seats in the Indian-American author Jhumpa 70-member Delhi Assembly. JANUARY Lahiri wins the $ 50,000 DSC prize Facebook launches Internet.org for Literature for her book, The in India at a function in Mumbai. Jan. 1: The Modi government sets Lowland . ICICI Bank launches the first dig- up NITI Aayog (National Institution Prime Minister Narendra Modi ital bank in the country, ‘Pockets’, on for Transforming India) in place of launches the Beti Bachao, Beti Pad- a mobile phone in Mumbai. the Planning Commission. hao (save daughters, educate daugh- Feb. 13: Srirangam witnesses The Karnataka High Court sets up ters) scheme in Panipat, Haryana. over 80 per cent turnout in bypolls. a Special Bench under Justice C.R. “Sukanya Samrudhi” account Sensex gains 289.83 points to re- Kumaraswamy to hear appeals filed scheme unveiled. claim 29000-mark on stellar SBI by AIADMK general secretary Jaya- Sensex closes at a record high of earnings. lalithaa in the disproportionate as- 29006.02 Feb. 14: Arvind Kejriwal takes sets case. Jan. 24: Poet Arundhati Subra- oath as Delhi’s eighth Chief Minis- The Tamil Nadu Governor K. Ro- manian wins the inaugural Khush- ter, at the Ramlila Maidan in New saiah confers the Sangita Kalanidhi want Singh Memorial Prize for Delhi. award on musician T.V. Gopalak- Poetry for her work When God is a Feb. -

Public Finance and Policy

Introduction to the Institute 39TH ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 NAT ONAL OF UBLIC FINANCE I NSTITUTE POLICY & page | 1 NIPFP Annual Report 2014-2015 ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 1ST, 2014 – MARCH 31ST, 2015 PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY: THE SECRETARY NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC FINANCE AND POLICY AN AUTONOMOUS RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNDER THE MINISTRY OF FINANCE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 18/2, SATSANG VIHAR Marg, SPECIAL INSTITUTIONAL AREA (NEAR JNU), NEW DELHI 110067 TEL.: 011 26569303, 26569780, 26569784 FAX: 91-11-26852548 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nipfp.org.in COMPILED, CONCEPT, DESIGN & EDITED BY: SAMREEN BADR COVER DESIGN, TEXT DESIGN ARTWORKS & PRINTED BY: VAP EMAIL: [email protected] TEL: 09811285510 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC FINANCE AND POLICY, NEW DELHI PROVIDING POLICY ADVICE SINCE 1976 2 | page Introduction to the Institute CONTENTS Introduction to the Institute5 Annexures List of Studies 2014-2015i Research Activities17 ii NIPFP Working Paper Seriesv Fiscal/Taxation-related Studies of Central and ii Internal Seminar Series v State Government19 iii Macroeconomic and Financial Sector Policy List of Governing Body Members as on 31.3.2015i Studies20 x List of Priced Publicationsx State Development Studies 24 iv Published Material of NIPFP Facultyx Other Studies28 ix New Projects initiated30 List of Staff Members as on 31.3.2015x Workshops, Seminars, Meetings and xv Conferences3 List of Sponsoring, Corporate, Permanent and 1 Ordinary Members as on 31.3.2015x Training Programmes38 xxi Finance and Accountsx NIPFP Publications (2014-2015)39 -

July 23, 2021 – Friday Key Developments Union Cabinet

July 23, 2021 – Friday Key Developments Union Cabinet approves Rs 6,322-cr PLI scheme for specialty steel The Union Cabinet on Thursday approved Rs 6,322-crore production linked incentive scheme for specialty steel, a move aimed at boosting domestic manufacturing and exports from the sector, Information and Broadcasting Minister Anurag Thakur said.He said that incentives worth Rs 6,322 crore will be provided over five years and it would create over 525,000 jobs. "It will boost manufacturing and help in reducing imports," he told reporters in New Delhi The PLI scheme would cover coated/plated steel products; high strength/wear resistant steel; specialty rails; alloy steel products, steel wires and electrical steel. "These steel products are used in a variety of applications which are both strategic and non-strategic and include white goods, automobile body parts and components, pipes for transportation of oil and gas, boilers, ballistic and armour sheets meant for defence application, high-speed railway lines, turbine components, electrical steel meant for power transformers and electric vehicles," said government in a statement. https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/union-cabinet-approves-rs-6-322-cr-pli-scheme-for- specialty-steel-121072200863_1.html Indian Finance Ministry officer among 25 global tax experts appointed to UN tax committee Rasmi Ranjan Das, a Joint Secretary in the Ministry of Finance, is among a distinguished group of 25 tax experts from around the world appointed as members of the UN tax committee for the 2021 to 2025 term. The committee, formally known as the UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, guides countries’ efforts to advance stronger and more forward-looking tax policies adapted to the realities of globalised trade and investment, an increasingly digitalised economy and worsening environmental degradation. -

India's Road to Development

India’s Road to Development Roel van der Veen June 2006 NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CLINGENDAEL CIP-Data Koninklijke bibliotheek, The Hague Van der Veen, R.J. India’s Road to Development / Roel van der Veen– The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Clingendael Diplomacy Papers No. 6 ISBN 90–5031–107-5 Desk top publishing by Desiree Davidse Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Clingendael Diplomatic Studies Programme Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phonenumber +31(0)70 - 3245384 Telefax +31(0)70 - 3746666 P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl The Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael is an independent institute for research, training and public information on international affairs. It publishes the results of its own research projects and the monthly ‘Internationale Spectator’ and offers a broad range of courses and conferences covering a wide variety of international issues. It also maintains a library and documentation centre. © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright-holders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Contents I. The Questions 2 II. The Start 6 III. The Past 16 IV. The Transition 28 V. The Comparison 36 VI. The Future 48 VII. The Lessons 54 1 I. The Questions India is an ancient civilization, rich in the arts and possessing intriguing wisdom. -

Is India Fit for a Role in Global Governance? the Predicament of Fragile Domestic Structures and Institutions

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Wulf, Herbert Working Paper Is India Fit for a Role in Global Governance? The Predicament of Fragile Domestic Structures and Institutions Global Cooperation Research Papers, No. 4 Provided in Cooperation with: University of Duisburg-Essen, Käte Hamburger Kolleg / Centre for Global Cooperation Research (KHK/GCR21) Suggested Citation: Wulf, Herbert (2014) : Is India Fit for a Role in Global Governance? The Predicament of Fragile Domestic Structures and Institutions, Global Cooperation Research Papers, No. 4, University of Duisburg-Essen, Käte Hamburger Kolleg / Centre for Global Cooperation Research (KHK/GCR21), Duisburg, http://dx.doi.org/10.14282/2198-0411-GCRP-4 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/214697 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

The Reception of a Concept: 'Governance' in India

Real Governance Change and Continuity in India’s Authority and Power Structures Jos Mooij 1. Introduction Governance has reached India. The country that for a long time was governed by the idea of planned economic development and the necessity of a powerful and omni- present government has been reinvented, as Corbridge and Harriss (2000) described the process. These authors have used this term to indicate that the previous model, which has never been fully implemented but functioned nevertheless as a powerful idea, has been replaced (partially) by a new model: market-led development, with a much smaller role for the state in development processes, and a much larger role for other actors. In other words, a shift from government to governance. The idea of governance, as Gopal Jayal and Pai (2001: 14-5) rightly stated, has different historical legacies. In the developed economies, it referred primarily to a changing political reality. New economic policies, cutbacks in the welfare state and critiques of bureaucratization led to new forms of public management. From a ‘command-and-control’ organization, the state became an enabling regulator. Out- contracting and agentification are just two of the main processes that can be witnessed. The discursive shift from government to governance can be seen as a response to these developments. In developing countries, however, the situation was different. The discourse “first landed on Southern shores as medicine prescribed by the good doctors of the Bretton Woods institutions, to remedy the laggard and inefficient development performance of these states” (Gopal Jayal and Pai, 2000: 14-15). As has been described already in the introduction to this book, for the World Bank and other international donors, governance became a convenient discursive mechanism to deal with issues of public management without giving a major role and responsibility to (often allegedly corrupt and inefficient) government institutions, and, moreover, to do so in a seemingly a-political fashion.