Quantifying Economic Reforms in India: Where Have We Been & What Lies Ahead, 1960 – 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Management Accountant

7+(0$1$*(0(17 THE MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANT ACCOUNTANT THE MANAGEMENT SEPTEMBER 2016 9 51 NO. VOL. 7+(-2851$/)25&0$V $&&2817$17 ,661 6HSWHPEHU92/123DJHV ÃÌÊ «iÌÌÛiiÃÃ ` 100 «iÝÌÞÊÌÊ v`iVi 7+(,167,787(2)&267$&&2817$1762),1',$ 6WDWXWRU\ERG\XQGHUDQ$FWRI3DUOLDPHQW ZZZLFPDLLQ www.icmai.in September 2016 The Management Accountant 1 2 The Management Accountant September 22016 www.icmai.in The Institute of Cost Accountants of India PRESIDENT THE INSTITUTE OF COST ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA CMA Manas Kumar Thakur (erstwhile The Institute of Cost and Works Accountants [email protected] of India) was first established in 1944 as a registered VICE PRESIDENT CMA Sanjay Gupta company under the Companies Act with the objects of [email protected] promoting, regulating and developing the profession of COUNCIL MEMBERS Cost Accountancy. CMA Amit Anand Apte, CMA Ashok Bhagawandas Nawal, On 28 May 1959, the Institute was established by a CMA Avijit Goswami, CMA Balwinder Singh, special Act of Parliament, namely, the Cost and Works CMA Biswarup Basu, CMA H. Padmanabhan, Accountants Act 1959 as a statutory professional body for CMA Dr. I. Ashok, CMA Niranjan Mishra, CMA Papa Rao Sunkara, CMA P. Raju Iyer, the regulation of the profession of cost and management CMA Dr. P V S Jagan Mohan Rao, accountancy. CMA P. V. Bhattad, CMA Vijender Sharma It has since been continuously contributing to the Shri Ajai Das Mehrotra, Shri K.V.R. Murthy, growth of the industrial and economic climate of the Shri Praveer Kumar, Shri Surender Kumar, country. Shri Sushil Behl The Institute of Cost Accountants of India is the only Secretary recognised statutory professional organisation and CMA Kaushik Banerjee, [email protected] licensing body in India specialising exclusively in Cost Sr. -

Magazine Can Be Printed in Whole Or Part Without the Written Permission of the Publisher

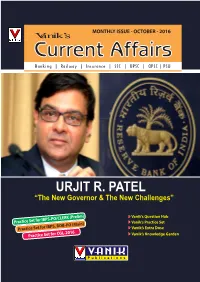

MONTHLY ISSUE - OCTOBER - 2016 CurrVanik’s ent Affairs Banking | Railway | Insurance | SSC | UPSC | OPSC | PSU URJIT R. PATEL “The New Governor & The New Challenges” Vanik’s Question Hub -PO/CLERK (Prelim) Practice Set for IBPS Vanik’s Practice Set -PO (Main) Practice Set for IBPS, BOB Vanik’s Extra Dose GL-2016 Practice Set for C Vanik’s Knowledge Garden P u b l i c a t i o n s VANIK'S PAGE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORTS OF INDIA NAME OF THE AIRPORT CITY STATE Rajiv Gandhi International Airport Hyderabad Telangana Sri Guru Ram Dass Jee International Airport Amristar Punjab Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport Guwaha ti Assam Biju Patnaik International Airport Bhubaneshwar Odisha Gaya Airport Gaya Bihar Indira Gandhi International Airport New Delhi Delhi Andaman and Nicobar Veer Savarkar International Airport Port Blair Islands Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport Ahmedabad Gujarat Kempegowda International Airport Bengaluru Karnatak a Mangalore Airport Mangalore Karnatak a Cochin International Airport Kochi Kerala Calicut International Airport Kozhikode Kerala Trivandrum International Airport Thiruvananthapuram Kerala Raja Bhoj Airport Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Devi Ahilyabai Holkar Airport Indore Madhya Pradesh Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport Mumbai Maharashtr a Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport Nagpur Maharashtr a Pune Airport Pune Maharashtra Zaruki International Airport Shillong Meghalay a Jaipur International Airport Jaipur Rajasthan Chennai International Airport Chennai Tamil Nadu Civil Aerodrome Coimbator e Tamil Nadu Tiruchirapalli International Airport Tiruchirappalli Tamil Nadu Chaudhary Charan Singh Airport Lucknow Uttar Pradesh Lal Bahadur Shastri International Airport Varanasi Uttar Pradesh Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose International Airport Kolkata West Bengal Message from Director Vanik Publications EDITOR Dear Students, Mr. -

The-Hindu-Special-Diary-Complete

THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 2 DIARY OF EVENTS 2015 THE HINDU THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 panel headed by former CJI R. M. Feb. 10: The Aam Aadmi Party NATIONAL Lodha to decide penalty. sweeps to power with 67 seats in the Indian-American author Jhumpa 70-member Delhi Assembly. JANUARY Lahiri wins the $ 50,000 DSC prize Facebook launches Internet.org for Literature for her book, The in India at a function in Mumbai. Jan. 1: The Modi government sets Lowland . ICICI Bank launches the first dig- up NITI Aayog (National Institution Prime Minister Narendra Modi ital bank in the country, ‘Pockets’, on for Transforming India) in place of launches the Beti Bachao, Beti Pad- a mobile phone in Mumbai. the Planning Commission. hao (save daughters, educate daugh- Feb. 13: Srirangam witnesses The Karnataka High Court sets up ters) scheme in Panipat, Haryana. over 80 per cent turnout in bypolls. a Special Bench under Justice C.R. “Sukanya Samrudhi” account Sensex gains 289.83 points to re- Kumaraswamy to hear appeals filed scheme unveiled. claim 29000-mark on stellar SBI by AIADMK general secretary Jaya- Sensex closes at a record high of earnings. lalithaa in the disproportionate as- 29006.02 Feb. 14: Arvind Kejriwal takes sets case. Jan. 24: Poet Arundhati Subra- oath as Delhi’s eighth Chief Minis- The Tamil Nadu Governor K. Ro- manian wins the inaugural Khush- ter, at the Ramlila Maidan in New saiah confers the Sangita Kalanidhi want Singh Memorial Prize for Delhi. award on musician T.V. Gopalak- Poetry for her work When God is a Feb. -

Public Finance and Policy

Introduction to the Institute 39TH ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 NAT ONAL OF UBLIC FINANCE I NSTITUTE POLICY & page | 1 NIPFP Annual Report 2014-2015 ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 1ST, 2014 – MARCH 31ST, 2015 PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY: THE SECRETARY NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC FINANCE AND POLICY AN AUTONOMOUS RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNDER THE MINISTRY OF FINANCE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 18/2, SATSANG VIHAR Marg, SPECIAL INSTITUTIONAL AREA (NEAR JNU), NEW DELHI 110067 TEL.: 011 26569303, 26569780, 26569784 FAX: 91-11-26852548 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nipfp.org.in COMPILED, CONCEPT, DESIGN & EDITED BY: SAMREEN BADR COVER DESIGN, TEXT DESIGN ARTWORKS & PRINTED BY: VAP EMAIL: [email protected] TEL: 09811285510 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC FINANCE AND POLICY, NEW DELHI PROVIDING POLICY ADVICE SINCE 1976 2 | page Introduction to the Institute CONTENTS Introduction to the Institute5 Annexures List of Studies 2014-2015i Research Activities17 ii NIPFP Working Paper Seriesv Fiscal/Taxation-related Studies of Central and ii Internal Seminar Series v State Government19 iii Macroeconomic and Financial Sector Policy List of Governing Body Members as on 31.3.2015i Studies20 x List of Priced Publicationsx State Development Studies 24 iv Published Material of NIPFP Facultyx Other Studies28 ix New Projects initiated30 List of Staff Members as on 31.3.2015x Workshops, Seminars, Meetings and xv Conferences3 List of Sponsoring, Corporate, Permanent and 1 Ordinary Members as on 31.3.2015x Training Programmes38 xxi Finance and Accountsx NIPFP Publications (2014-2015)39 -

CENTRE for DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS at the DELHI SCHOOL of ECONOMICS

CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS at the DELHI SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS __________________________________________________ The Twenty First Annual Report A U G U S T 2 0 1 4 __________________________________________________ CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS DELHI SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF DELHI DELHI 110007 1 C O N T E N T S Page Nos. Introduction Research Activity Publications 7-9 Invited Talks/Conferences/Seminars 10-12 Working Papers 13 Research Projects 14-19 Conferences, Seminars and other Activities 20-25 organized by the CDE during 2013 – 14 Computing Facilities & Databases, Library and Visitors 26-27 and Office Staff 2 I N T R O D U C T I O N The Centre for Development Economics (CDE) was set up with a generous grant from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India as a research adjunct at the Delhi School of Economics (Department of Economics) to provide better research facilities to the faculty and the students of the Department of Economics. It is a non-profit organization that supports research in all areas of Economics. It came into existence in August 1992 and began effectively functioning from early 1993, with the full range of activities picking up only in late 1993 after it received its grants from the Government of India and the Ford Foundation. A I M S To promote and disseminate research; To sponsor economists from all over India and abroad to visit to Delhi School of Economics; To conduct regular conferences and workshops; To upgrade research infrastructure, including communication and computing facilities. 3 THE COUNCIL Sunil Kanwar Anirban Kar Executive Director Managing Director Suata Bag Ram Singh Secretary Treasurer Aditya Bhattacharjea J. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

The Political Economy of Hindu Nationalism in India 1998-2004

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA 1998-2004 submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Politics and International Relations John Joseph Abraham Royal Holloway, University of London 1 2 Declaration of Authorship I John Joseph Abraham hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: John Joseph Abraham August 22, 2014 3 4 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to a number of people who have made this project possible. I thank my supervisors Dr. Yasmin Khan and Dr. Oliver Heath for their careful guidance, constant support and enthusiasm over these years. Thanks is also due to Dr. James Sloam for his insights at important stages of this project. Finally I would like to thank Dr. Tony Charles for his valuable support in the final stages of this work. I thank Dr. Nathan Widder under whose leadership the Department of Politics and International Relations has been a supportive environment and congenial forum for the development of ideas and Dr. Jay Mistry, Dr. Ben O'Loughlin, Dr. Sandra Halperin and Anne Uttley for the important roles they have played in my development as an academic scholar. Finally, thanks is due to my fellow researchers, Shyamal Kataria, Baris Gulmez, Didem Buhari, Celine Tschirhart, Ali Mosadegh Raad, Braham Prakash Guddu and Mark Pope for the many useful conversations and sympathetic understanding. This project would have not been possible but for the help of my family. I would like to thank my parents Abraham and Valsa Joseph as well as George and Annie Mathew for their constant encouragement and eager support. -

SMVD Poly Pack Private Limited” Under the Provisions of the Companies Act, 1956 with the Deputy Registrar of Companies, West Bengal

PROSPECTUS Dated: December 06, 2017 Please read Section 26 of the Companies Act, 2013 100% Fixed Price Issue SMVD POLY PACK LIMITED Our Company was originally incorporated on January 28, 2010, in the name and style of “SMVD Poly Pack Private Limited” under the provisions of the Companies Act, 1956 with the Deputy Registrar of Companies, West Bengal. Subsequently, our Company was converted into a public company pursuant to special resolution passed by the members of the Company at the Extra Ordinary General Meeting of our Company held on July 31, 2017 and the name of our Company was changed to “SMVD Poly Pack Limited” and a Fresh Certificate of Incorporation consequent upon conversion to public limited Company dated August 22, 2017 was issued by the Registrar of Companies, Kolkata, bearing Corporate Identity Number U25200WB2010PLC141483. For further details of the changes in our name and registered office of our Company, please refer to the section titled “History and Certain Corporate Matters” on page 126 of this Prospectus. Registered Office: 71, BRB., Basu Road, Block - A, Room No. 513, Kolkata, West Bengal-700001 Works: Village Srirampur, P.O. Mullickpur, P.S. Baruipur, District 24 Parganas, Kolkata-700145 Contact Person: Mr. Prateek Agarwal, Company Secretary and Compliance Officer Tel No.: 033-22350460; Fax No. : N.A. Email: [email protected]; Website: www.smvdpolypack.com PROMOTERS OF THE COMPANY MR. PRAMOD KUMAR AGARWAL, MS. SANGITA AGARWAL, AND AASHAKIRAN COMMODEAL PRIVATE LIMITED INITIAL PUBLIC ISSUE OF 16,40,000 EQUITY SHARES OF FACE VALUE OF ₹10 EACH (THE “ EQUITY SHARES”) OF SMVD POLY PACK LIMITED (“SMVD” OR THE “COMPANY”) FOR CASH AT A PRICE OF ₹ 55 PER SHARE (THE “ISSUE PRICE”), AGGREGATING TO ₹ 902.00 LAKHS (THE “ISSUE”), OF WHICH, 84,000 EQUITY SHARES OF ₹ 10 EACH WILL BE RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIPTION BY MARKET MAKERS TO THE ISSUE (“MARKET MAKER RESERVATION PORTION”). -

Download Arogya Setu App for Those Living in Hotspot Areas of the State

Monthly Current AffairsTitle Capsule & Quiz MayTitle 2020 The countries placed on the list by the Trump administration on intellectual property (IP) related issues are Algeria, Argentina, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Ukraine and Venezuela. According to the World Intellectual Property International Labour Day: 1 May Right Organization, the Intellectual Property is the creation of literary and artistic works, symbols, names, images. World Tuna Day: 02 May Labour Day or International Workers' Day is observed each year on the first day of May to celebrate achievements of the working class. The day, also called 'May Day', is also observed as a public holiday in many countries. On 1 May, 1886, labour unions in the US decided to go on a strike demanding that World Tuna Day is observed on May 2 every year. workers should not be made to work for more than 8 hours a day. The United Nations (UN) established the Just three days after the strike began, a blast World Tuna Day to raise awareness about the occurred in Chicago's Haymarket Square tuna fish and its importance to humans and leaving many dead. earth. To honor those who died in the blast, the It is also observed to promote more International Socialist Conference declared 1 sustainable fishing practices. May as a day designated for labourers. The United Nations general assembly officially voted in favour of observing World US places India on priority watch list for Tuna Day in the year 2016. intellectual property protection World Tuna Day was observed for the first time in the year 2017. -

India Abroad Person of the Year Awards Honor the Community's Star Achievers

ADVERTISEMENT PERIODICAL Friday, March 19, 2010 Vol. XL No.25 www.rediff.com (Nasdaq: REDF) $1 International Weekly Newspaper Chicago/Dallas Los Angeles NY/NJ/CT New York Toronto PERIODICAL INDEX Letters to the Editor..........................................A2 People...................................................................A4 Immigration.....................................................A30 Business............................................................A24 Community.......................................................A34 Magazine..........................................................M1 Sports................................................................A32 Pages: 52+24=76 Friday, March 19, 2010 Vol. XL No.25 www.rediff.com (Nasdaq: REDF) NEW YORK EDITION $1 International Weekly Newspaper Chicago/Dallas Los Angeles NY/NJ/CT New York Toronto Winners All SUMAN GUHA MOZUMDER The India Abroad Person of the Year awards honor the community's star achievers To subscribe 1-8877-IINDIA-AABROAD (1-877-463-4222) www.indiaabroad.com/subscribe ADVERTISEMENT The International Weekly Newspaper founded in 1970. Member, Audit Bureau of Circulation A225 India Abroad March 19, 2010 INDIA ABROAD (ISSN 0046 8932) is published every Friday by India Abroad LETTERS Publications, Inc. 42 Broadway, 18th floor, New York, NY 10004. Annual subscription in United States: $32. Canada $26. India $32 INTERNATIONAL: By Regular Mail: South America, the Caribbean, Europe, Africa, Australia & Middle East: $90. By Airmail: South America, the Caribbean, -

How China Brings India and America Closer the Uses of Adversity

www.openthemagazine.com 50 27 JULY /2020 OPEN VOLUME 12 ISSUE 29 27 JULY 2020 CONTENTS 27 JULY 2020 5 6 12 14 16 18 LOCOMOTIF OPEN DIARY INDIAN ACCENTS TOUCHSTONE WHISPERER OPEN ESSAY The missing rebel By Swapan Dasgupta The ideal king The rot in rhetoric By Jayanta Ghosal The uses of adversity By S Prasannarajan By Bibek Debroy By Keerthik Sasidharan By Mohan Malik 22 SELF-RELIANCE IN A BRAVE NEW WORLD By Siddharth Singh 28 HOMEMADE From Reliance Jio’s Made-in-India 5G 22 plan to the recent boom in desi apps and PPE manufacturing, Indian industry gets ready for a swadeshi turn By Lhendup G Bhutia 34 THE INWARD GAZE 38 The evolution of self-reliance from Gandhi’s village ideal to Modi’s national vision By Madhavankutty Pillai 38 THE JAIPUR JOLT Sachin Pilot becomes the face of rebellion in a party on the brink By PR Ramesh 50 44 FOR GOD’S SAKE By restoring the management of Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple to the Travancore royal family, the Supreme Court raises the larger question of the state’s control over temples 44 By J Sai Deepak 56 50 THE OTHER STORY FROM KASHMIR A new spirit of entrepreneurship sprouts across the Valley By Kaveree Bamzai 56 60 64 66 MURDER ON THEIR MINDS NOBODY’S NOVELIST THE HOPEFUL HISTORIAN NOT PEOPLE LIKE US Portrayals of psychiatrists on Ottessa Moshfegh’s new book establishes Rutger C Bregman’s new book Alarm bells recent web shows use psychology her prowess at excavating the minds of questions our shared assumptions By Rajeev Masand to titillate or trivialise characters on the margins of society about humanity