Stuart Dybek May 18, 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

My Town: Writers on American Cities

MY TOW N WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES MY TOWN WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud .......................................... 2 THE POETRY OF BRIDGES by David Bottoms ........................... 7 GOOD OLD BALTIMORE by Jonathan Yardley .......................... 13 GHOSTS by Carlo Rotella ...................................................... 19 CHICAGO AQUAMARINE by Stuart Dybek ............................. 25 HOUSTON: EXPERIMENTAL CITY by Fritz Lanham .................. 31 DREAMLAND by Jonathan Kellerman ...................................... 37 SLEEPWALKING IN MEMPHIS by Steve Stern ......................... 45 MIAMI, HOME AT LAST by Edna Buchanan ............................ 51 SEEING NEW ORLEANS by Richard Ford and Kristina Ford ......... 59 SON OF BROOKLYN by Pete Hamill ....................................... 65 IN SEATTLE, A NORTHWEST PASSAGE by Charles Johnson ..... 73 A WRITER’S CAPITAL by Thomas Mallon ................................ 79 INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud ore than three-quarters of Americans live in cities. In our globalized era, it is tempting to imagine that urban experiences have a quality of sameness: skyscrapers, subways and chain stores; a density of bricks and humanity; a sense of urgency and striving. The essays in Mthis collection make clear how wrong that assumption would be: from the dreamland of Jonathan Kellerman’s Los Angeles to the vibrant awakening of Edna Buchanan’s Miami; from the mid-century tenements of Pete Hamill’s beloved Brooklyn to the haunted viaducts of Stuart Dybek’s Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago; from the natural beauty and human diversity of Charles Johnson’s Seattle to the past and present myths of Richard Ford’s New Orleans, these reminiscences and musings conjure for us the richness and strangeness of any individual’s urban life, the way that our Claire Messud is the author of three imaginations and identities and literary histories are intertwined in a novels and a book of novellas. -

On and Off the Cliff

The Newsletter of The Cliff Dwellers ON AND OFF THE CLIFF Volume 36, Number 6 November-December 2014 Enjoy the Holidays! Tues., Dec. 9 – “The Most Sat., Dec. 13: Holiday Wonderful Time of the Candlelight Dinner Party Year” A performance of for Members! Holiday Music brought to Sparkling seasonal decor and us by Laura Freeman, glowing candles! A four Beckie Menzie & course gourmet dinner by Marianne Murphy Chef Victor and musical Orland--between 5:30 and interludes played by Cliff 7:30. Dweller Arnie Lanza. An elegant evening! Wed., Dec. 10: Members Art Fri., Dec. 19: Members Holiday Exhibition Opening Lunch Reception featuring artwork byFred Wackerle CD'09, Sat., De 20: Children’s Party Tobin Richter CD'04, Steven for Members’ Children and Backman CD'11, James Grandchildren Smith CD'84, Alan Alongi CD’12, and Debbie Hunter The Club will be closed until Mon., Jan. 5, 2015. Snow CD’13. Celebrate a Good Year on the Cliff! 1 Volume 36, Number 6 November-December 2014 Abner Mikva Receives Presidential Medal of Freedom By Mike Deines CD’03 In a White House ceremony on November 24, Abner Mikva CD’03 was among 19 American citizens awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, our nation’s highest honor bestowed upon American civilians for “extraordinary contributions to our country and the world.” Mikva received the medal from President Obama for “contributions to U.S. security, world peace, and culture.” He holds the distinction of having served in all three branches of government—as a five-term Democrat congressman from Illinois, as a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. -

Loyola University Chicago

Loyola Ramblin’ (wo)man on the street { hat is yor faorite holiday tradition } INSIDE Jeremy Boni / General Manager, Ellen Landgraf, CPA, PhD / Associate Professor, Accounting Chris M. Murphy / Associate Vice President for Mission Loyola University Chicago Bookstores “Every year of my life I have been fortunate to have a real Christmas and Ministry, Director of University Ministry “My family and I stay up all night on Thanksgiving, tree at home. This tradition appeared to be threatened some years “Our family opens gifts on Christmas Day, but saves the playing cards and board games. Then we go out shopping back when I purchased a Mini Cooper (which would not accommodate stocking stuffers for last. The stockings are fi lled with small at 4 a.m. to catch all the “Black Friday” shopping deals. We my need for a seven foot balsam!). Thank goodness for the World gifts, unwrapped, that family members fi nd throughout the always like to watch how focused, and sometimes intense, Wide Web. I am now able to procure my real tree, fresh-cut from year. Each gift somehow refl ects the persona of the person NEWS FOR FACULTY AND STAFF LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO | DEC 2007 people get about shopping. Back in Ohio, “Black Friday” is New Hampshire. It comes in a 10 foot by 15 inch rectangular box via receiving the gift. It is a fun challenge to keep one’s eyes open Loyola a serious event!” FedEx. We call it the tree-in-a-box.” throughout the whole year for just the right small memento.” VP, University Marketing Director of Communications Contributors Photography Graphic Designer & Communications Maeve Kiley Annie Busiek, Steve Christensen, Mark Beane Alisha Roeder Kelly Shannon Annie Hughes, Brendan Keating, Kathleen Neuman, Lenzlee Ruiz Inside Loyola is published by Loyola University Chicago, Division of University Marketing and Communications, 820 N. -

Shelf Life: Fall 2014

SHELF LIFE NEWS FOR FACULTY & FRIENDS • FALL 2014 LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO LIBRARIES University Libraries to kick off fundraising campaign ean Bob Seal recently announced tiful space to showcase, preserve, and make portant historical institutional documents and a campaign to raise $1.5 million available the University’s treasures.” Recent gifts photographs; oral histories; and much more. to renovate Special Collections in of significance include first American editions of “The new space will not only be a place Cudahy Library. The project will Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry to exhibit our valuable materials and be a Dinvolve creating a modernized rare books and Finn; two rare Torah scrolls, one from the 17th comfortable, attractive location for researchers archives reading room, building an office for the century; the Melville Steinfels papers; more and staff, but it will attract additional donors of Head of Special Collections, Kathy Young, dou- than 100 rare books from the Chiswick Press rare books, archival collections, and funds,” said bling the size of the rare books vault, expanding in London; 19th century British caricature and Dean Seal. “The new space will also be more ap- and improving the staff work area, and upgrad- books illustrated by George Cruikshank and his propriate for class visits which are occurring at ing infrastructure. Revamped infrastructure will contemporaries; and a large collection of works an increasing rate as the size and quality of our include a new security system, a replacement illustrated and written by Edward Gorey. collections grow and become more well known.” for the outdated fire suppression system, new Other important materials include the papers The dean and the Office of University wiring and data lines, and a self-contained of Samuel Insull, secretary to Thomas Edison Advancement are working together to raise environmental control system. -

The Hank Center for the Catholic Intellectual Heritage

The Hank Center for the Catholic Intellectual Heritage November 2015 From the Desk of Fr. Mark Bosco, S.J. Dear Friends and Colleagues, The Hank Center is in the home stretch of its programing for the semester, climaxing next week with our third in a series of conferences on Catholic immigration in Chicago. This year, the conference looks at the historical, cultural, and religious influence of the Polish-American community. It is often said that the second largest Polish city in the world is Chicago-that only Warsaw has a larger concentration of Poles. I can believe it as I see their presence on Loyola's campus each year. I usually have at least one or two students in my undergraduate courses that still speak Polish at home. Some of my students came over with their families after the fall of Communism; others are third and fourth generation Polish-Americans who still know their language and celebrate many of their Polish customs. Organized by Loyola's director of Polish Studies, Bozena McLees, it has been an enlightening experience for me, as I see just how deeply this community has impacted Chicago. One of the plenary speakers for this conference is the renowned Chicago writer, Stuart Dybek, who just happens to be a Loyola alum. His award-winning collection, The Coast of Chicago, weaves together a patchwork of stories that offer the reader a glimpse of Chicago life, especially in the 1960s and 70s. Join us for his talk Saturday morning at 9:30 in McCormick Lounge. All are welcome. We end the semester with our Faith in Focus Film Series. -

Musings Fall 2016.Indd

Fall 2016 THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH English Graduate Newsletter Volume XX • Number 1 INSIDE Natasha Trethewey joins the department 2 NNewew SStudentstudents aandnd GGraduateraduate PPlacementlacement 4 EExcellencexcellence iinn MentoringMentoring IInitiativenitiative 6 TTracyracy CC.. DDavisavis FFacultyaculty aandnd GGraduateraduate SStudenttudent NNewsews 8 Alumni News and Publications 15 Interviews with Jeffrey Masten and 17 Kelly Wisecup A letter from Betty Farrar, M.A. ‘58 19 From the Chair he new academic year fi nds the English Department, as always, fl ying out of the starting gates of Fall Quarter. In addition to the reliable intellectual feast of course offerings this T year, we continue to host visitors presenting their work to us on a range of subjects from medieval to the post-modern / post-human. Indeed, with that pair of “posts,” we might begin to consider what comes next in the rapidly emerging history of English Studies. English departments have long served as incubators and safe harbors for interdisciplinary work, work that even goes on, sometimes, to evolve into new disciplines and academic units. The sheer diversity of kinds of inquiry that English has hosted is a point of great pride for our department, and we continue to cheer on the powerful creativity of our faculty and graduate students, as we all press upon the boundaries of what and how it has been possible to think, and to write – so far. Within the Department, as well, we work to forge new kinds of intellectual connections: we are putting the fi nal polish on a proposal for an MFA / MA degree that will bring our two departmental enterprises in creative writing and literary criticism ever closer together. -

WRITING MATTERS the Electronic NU Writing Event Digest, Please Send an Email Fall 2007 Vol

See NU STUDY MATRIX for a complete listing of ALL writing courses offered at NU www.northwestern.edu/writing-arts/study.html THE NEWSLETTER OF NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY’S CENTER FOR THE WRITING ARTS VOL. 8WRITING NO. 1 MATTERSFall 2007 CWA 2007 FALL QUARTER SYMPOSIA The Black Arts Movement in the Broader International Day of Writing Legacy of the Civil Rights Movement Friday Tuesday October 26, 2007 October 16, 2007 2:30-4:30 p.m. 2:00-5:00 p.m. Harris Hall, Room 108, Reception follows 1881 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL Norris University Center Northwestern Room, Our visitors from Indonesia, Egypt, Russia, Hong 1999 Campus Drive, Evanston, IL Kong, Bulgaria, and Australia are currently in residence at the International Writing Workshop The panelists will be Angela Jackson, poet, novelist at the University of Iowa. The writers will and playwright; Sterling Plumpp, poet, scholar, editor present brief readings of their work in and activist; Carolyn Rodgers, poet, feminist and translation, and a discussion of literary cultures educator; and Sala Udin, Freedom Rider, actor in the and literary practices will follow. establishment of the Pittsburgh Black Horizons Theatre, under the direction of his childhood friends, Rob Penny Guest writers are: and August Wilson, elected member of the Pittsburgh Nirwan Dewanto, Indonesia City Council, where he served for 11 years. Hamdy El Gazzar, Egypt Ksenia Golubovich, Russia Co-sponsored by the Center for the Writing Arts, the Lawrence Pun, Hong Kong Departments of African-American Studies, English, and Political Science, and the Office of the Dean of the Weinberg Aziz Nazmi Shakir-Tash, Bulgaria School of Arts and Sciences. -

Recent Polish-American Fiction

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Modern Languages and Literatures: Faculty Faculty Publications and Other Works by Publications and Other Works Department 1-1998 Recent Polish-American Fiction John A. Merchant Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/modernlang_facpubs Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Modern Languages Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation John Merchant. "Recent Polish-American Fiction," The Sarmatian Review, Vol. XVIII, No. 1, January 1998, 501-508. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications and Other Works by Department at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages and Literatures: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Polish Institute of Houston at Rice University, 1998. January 1998 THE SARMATIAN REVIEW 501 Dybek’s characters ‘constantly assess themselves within Recent Polish-American the context of place’ (Princes and Peasants 256). Dybek’s characters, generally young boys or young men, roam Fiction through and explore the playgrounds of their own ethnicity; leaving the neighborhood is a form of emigration and, to these characters, a cultural loss. John Merchant What is left at the end of Dybek’s work is a new There has always been a Polish-American voice kind of ethnic identity. -

Creative Writing

MA/MFA PROGRAM Creative Writing Choose from specializations in fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. INDEPENDENT Find your voice. STUDY Develop your craft. PUBLISHING MASTER OF ARTS/MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN CREATIVE WRITING The part-time graduate program in creative writing provides students the opportunity to grow as artists within the specializations of fiction, poetry and creative nonfiction. TEACHING PRACTICUM Develop your craft in workshops taught by a faculty of esteemed writers. The creative writing program offers flexible scheduling and pacing that allows students to balance work, personal life, and artistic practice. ELECTIVES In both degree tracks — the Master of Arts in Creative Writing (MA) and the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing (MFA) — the curriculum challenges students to read like writers, and includes courses in literature, publishing, and various aesthetic approaches to the craft of writing. In small group workshops, award-winning faculty members lead discussions that help students examine and address strengths and weaknesses in their writing, as well as open up possibilities for revision. THESIS During the thesis quarters, students work one-on-one with faculty to explore deeper aspects of their work and create polished manuscripts. The program includes numerous opportunities for study beyond the classroom. Students may gain experience in publishing by serving as staff of TriQuarterly, the program’s international online literary journal, or by interning at publishing houses. Teaching seminars and related internships also prepare students for teaching careers. While earning their degrees, students connect with other writers at readings and related events that are part of Chicago’s vibrant literary scene. -

Reading Group Guide Spotlight

Spotlight on: Reading Group Guide I Sailed With Magellan Author: Stuart Dybek Much of Stuart Dybek’s fictional world addresses adolescent life in Chicago’s immigrant neighborhoods. Though often considered a member of a long tradition of Chicago writers such as Gwendolyn Brooks and Saul Bellow, Dybek is known for blurring the lines between the real and the magical, which sets his work apart from the realism of other Chicago writers. Biographical Information: Dybek was born on April 10, 1942, in an immigrant neighborhood on the southwest side of Chicago. His father, Stanley, was a foreman in an International Harvester Plant, and his mother, Adeline, was a truck dispatcher. Dybek developed an interest in music at a young age and has said that jazz music has been an important influence on his development as a writer. He attended a Catholic high school, but soon rejected the strictures of the Catholic church. Upon graduation, Dybek entered Loyola University of Chicago as a pre-med student. He dropped out to devote himself to the peace and civil rights movements, but returned later to receive both his bachelor’s (1964) and master’s (1968) degrees. Dybek worked as a case worker for the Cook County Department of Public Aid, and a teacher in an elementary school in a Chicago suburb. He also worked in advertising, and then, from 1968 to 1970, he taught at a high school on the island of Saint Thomas. In 1970 Dybek turned his focus to writing; he entered the Master of Fine Arts program at the University of Iowa where he received an M.F.A. -

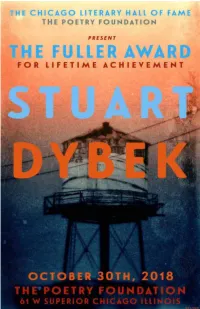

FULLER AWARD for LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT 1 CONTENTS Tonight’S Program

FULLER AWARD FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT 1 CONTENTS Tonight’s Program .......................................................................................3 The Fuller Award .....................................................................................4-5 Bibliography .............................................................................................6-7 Awards & Recognitions ..........................................................................8-9 Tonight’s Participants ..........................................................................10-13 Chicago Lives Inside Her ...................................................................14-20 Circling Back: Chicago, Stories, and Remembrance.......................21-28 The House on Campbell Avenue .......................................................29-31 Tributes .................................................................................................32-66 Co-Presenter Tributes ...............................................................................67 Sponsor Tributes ..................................................................................68-71 Chicago Literary Hall of Fame ................................................................72 Selection Committee .................................................................................73 Special Thanks ...........................................................................................74 Chicago Classics CLHOF Series ..............................................................75