Reading Group Guide Spotlight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

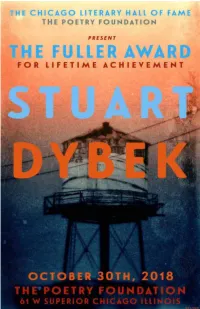

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

Thomas Pynchon: a Brief Chronology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 6-23-2005 Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology Paul Royster University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Royster, Paul, "Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology" (2005). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Thomas Pynchon A Brief Chronology 1937 Born Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr., May 8, in Glen Cove (Long Is- land), New York. c.1941 Family moves to nearby Oyster Bay, NY. Father, Thomas R. Pyn- chon Sr., is an industrial surveyor, town supervisor, and local Re- publican Party official. Household will include mother, Cathe- rine Frances (Bennett), younger sister Judith (b. 1942), and brother John. Attends local public schools and is frequent contributor and columnist for high school newspaper. 1953 Graduates from Oyster Bay High School (salutatorian). Attends Cornell University on scholarship; studies physics and engineering. Meets fellow student Richard Fariña. 1955 Leaves Cornell to enlist in U.S. Navy, and is stationed for a time in Norfolk, Virginia. Is thought to have served in the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. 1957 Returns to Cornell, majors in English. Attends classes of Vladimir Nabokov and M. -

Throughout His Writing Career, Nelson Algren Was Fascinated by Criminality

RAGGED FIGURES: THE LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN NELSON ALGREN AND RALPH ELLISON by Nathaniel F. Mills A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney For graduate students on the left ii Acknowledgements Indebtedness is the overriding condition of scholarly production and my case is no exception. I‘d like to thank first John Callahan, Donn Zaretsky, and The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for permission to quote from Ralph Ellison‘s archival material, and Donadio and Olson, Inc. for permission to quote from Nelson Algren‘s archive. Alan Wald‘s enthusiasm for the study of the American left made this project possible, and I have been guided at all turns by his knowledge of this area and his unlimited support for scholars trying, in their writing and in their professional lives, to negotiate scholarship with political commitment. Since my first semester in the Ph.D. program at Michigan, Marjorie Levinson has shaped my thinking about critical theory, Marxism, literature, and the basic protocols of literary criticism while providing me with the conceptual resources to develop my own academic identity. To Patricia Yaeger I owe above all the lesson that one can (and should) be conceptually rigorous without being opaque, and that the construction of one‘s sentences can complement the content of those sentences in productive ways. I see her own characteristic synthesis of stylistic and conceptual fluidity as a benchmark of criticism and theory and as inspiring example of conceptual creativity. -

The Proliferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nelson Algren

THE PROLIFERATION OF THE GROTESQUE IN FOUR NOVELS OF NELSON ALGREN by Barry Hamilton Maxwell B.A., University of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department ot English ~- I - Barry Hamilton Maxwell 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Barry Hamilton Maxwell DEGREE: M.A. English TITLE OF THESIS: The Pro1 iferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nel son A1 gren Examining Committee: Chai rman: Dr. Chin Banerjee Dr. Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor - Dr. Evan Alderson External Examiner Associate Professor, Centre for the Arts Date Approved: August 6, 1986 I l~cr'ct~ygr.<~nl lu Sinnri TI-~J.;~;University tile right to lend my t Ire., i6,, pr oJcc t .or ~~ti!r\Jc~tlcr,!;;ry (Ilw tit lc! of which is shown below) to uwr '. 01 thc Simon Frasor Univer-tiity Libr-ary, and to make partial or singlc copic:; orrly for such users or. in rcsponse to a reqclest from the , l i brtlry of rllly other i111i vitl.5 i ty, Or c:! her- educational i r\.;t i tu't ion, on its own t~l1.31f or for- ono of i.ts uwr s. I furthor agroe that permissior~ for niir l tipl c copy i rig of ,111i r; wl~r'k for .;c:tr~l;rr.l y purpose; may be grdnted hy ri,cs oi tiI of i Ittuli I t ir; ~lntlc:r-(;io~dtt\at' copy in<) 01. -

An American Outsider

Nelson Algren: An American Outsider Bettina Drew VER THE MANY YEARS IHAVE SPENT WRITING AND THINKING ABOUT Nelson Algren, I have always found, in addition to his poetic lyri- clsm, a density and darkness and preoccupation with philosoph- .nl issues that seem fundamentally European rather than Amer- ican. In many ways, Norman Mailer was right when he called Algren "the grand odd-ball of American Ietters."' There is some- thing accurate in the description, however pejorative its intent or meaning at first glance, for Algren held consistently and without doubt to an artistic vision that, above and beyond its naturalism, was at odds with the mainstream of American literature. And cul- ural reasons led to the lukewarm American reception of his work ill the past several decades. As James R. Giles notes in his book Confronting the Horror: The Novels of Nelson Algren, a school of critical thought citing Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman argues that nineteenth-century American liter- ature was dominated by an innocence and an intense faith in in- dividual freedom and human potential. But nineteenth-century American literature was also dominated by an intense focus on the American experience as unique in the world, a legacy, perhaps, of --. the American Revolution against monarchy in favor of democ- racy. Slave narratives, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852),narratives of westward discovery such as Twain's Roughing It (1872), the wilderness tales of James Fenimore Cooper, and Thoreau's stay on Walden Pond were stories that could have taken place only in America-an essentially rural and industrially unde- veloped America. -

My Town: Writers on American Cities

MY TOW N WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES MY TOWN WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud .......................................... 2 THE POETRY OF BRIDGES by David Bottoms ........................... 7 GOOD OLD BALTIMORE by Jonathan Yardley .......................... 13 GHOSTS by Carlo Rotella ...................................................... 19 CHICAGO AQUAMARINE by Stuart Dybek ............................. 25 HOUSTON: EXPERIMENTAL CITY by Fritz Lanham .................. 31 DREAMLAND by Jonathan Kellerman ...................................... 37 SLEEPWALKING IN MEMPHIS by Steve Stern ......................... 45 MIAMI, HOME AT LAST by Edna Buchanan ............................ 51 SEEING NEW ORLEANS by Richard Ford and Kristina Ford ......... 59 SON OF BROOKLYN by Pete Hamill ....................................... 65 IN SEATTLE, A NORTHWEST PASSAGE by Charles Johnson ..... 73 A WRITER’S CAPITAL by Thomas Mallon ................................ 79 INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud ore than three-quarters of Americans live in cities. In our globalized era, it is tempting to imagine that urban experiences have a quality of sameness: skyscrapers, subways and chain stores; a density of bricks and humanity; a sense of urgency and striving. The essays in Mthis collection make clear how wrong that assumption would be: from the dreamland of Jonathan Kellerman’s Los Angeles to the vibrant awakening of Edna Buchanan’s Miami; from the mid-century tenements of Pete Hamill’s beloved Brooklyn to the haunted viaducts of Stuart Dybek’s Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago; from the natural beauty and human diversity of Charles Johnson’s Seattle to the past and present myths of Richard Ford’s New Orleans, these reminiscences and musings conjure for us the richness and strangeness of any individual’s urban life, the way that our Claire Messud is the author of three imaginations and identities and literary histories are intertwined in a novels and a book of novellas. -

Pete Segall. the Voice of Chicago in the 20Th Century: a Selective Bibliographic Essay

Pete Segall. The Voice of Chicago in the 20th Century: A Selective Bibliographic Essay. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. December, 2006. 66 pages. Advisor: Dr. David Carr Examining the literature of Chicago in the 20th Century both historically and critically, this bibliography attempts to find commonalities of voice in a list of selected works. The paper first looks at Chicago in a broader context, focusing particularly on perceptions of the city: both Chicago’s image of itself and the world’s of it. A series of criteria for inclusion in the bibliography are laid out, and with that a mention of several of the works that were considered but ultimately disqualified or excluded. Before looking into the Voice of the city, Chicago’s history is succinctly summarized in a bibliography of general histories as well as of seminal and crucial events. The bibliography searching for Chicago’s voice presents ten books chronologically, from 1894 to 2002, a close examination of those works does reveal themes and ideas integral to Chicago’s identity. Headings: Chicago (Ill.) – Bibliography Chicago (Ill.) – Bibliography – Critical Chicago (Ill.) – History Chicago (Ill.) – Fiction THE VOICE OF CHICAGO IN THE 20TH CENTURY: A SELECTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY by Pete Segall A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina December 2006 Approved by _______________________________________ Dr. David Carr 1 INTRODUCTION As of this moment, a comprehensive bibliography on the City of Chicago does not exist. -

An Evening to Honor Gene Wolfe

AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE Program 4:00 p.m. Open tour of the Sanfilippo Collection 5:30 p.m. Fuller Award Ceremony Welcome and introduction: Gary K. Wolfe, Master of Ceremonies Presentation of the Fuller Award to Gene Wolfe: Neil Gaiman Acceptance speech: Gene Wolfe Audio play of Gene Wolfe’s “The Toy Theater,” adapted by Lawrence Santoro, accompanied by R. Jelani Eddington, performed by Terra Mysterium Organ performance: R. Jelani Eddington Closing comments: Gary K. Wolfe Shuttle to the Carousel Pavilion for guests with dinner tickets 8:00 p.m Dinner Opening comments: Peter Sagal, Toastmaster Speeches and toasts by special guests, family, and friends Following the dinner program, guests are invited to explore the collection in the Carousel Pavilion and enjoy the dessert table, coffee station and specialty cordials. 1 AN EVENING TO HONOR GENE WOLFE By Valya Dudycz Lupescu A Gene Wolfe story seduces and challenges its readers. It lures them into landscapes authentic in detail and populated with all manner of rich characters, only to shatter the readers’ expectations and leave them questioning their perceptions. A Gene Wolfe story embeds stories within stories, dreams within memories, and truths within lies. It coaxes its readers into a safe place with familiar faces, then leads them to the edge of an abyss and disappears with the whisper of a promise. Often classified as Science Fiction or Fantasy, a Gene Wolfe story is as likely to dip into science as it is to make a literary allusion or religious metaphor. A Gene Wolfe story is fantastic in all senses of the word. -

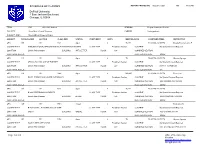

SCHEDULE of CLASSES Depaul University 1 East Jackson

SCHEDULE OF CLASSES REPORT PRINTED ON: August 13, 2021 AT: 11:42 AM DePaul University 1 East Jackson Boulevard Chicago, IL 60604 TERM: 1080 2021-2022 Autumn SESSION: Regular Academic Session COLLEGE: Liberal Arts & Social Sciences CAREER: Undergraduate SUBJECT AREA: African&Black Diaspora Studies SUBJECT CATALOG NBR SECTION CLASS NBR STATUS COMPONENT UNITS MEETING DAYS START/END TIMES INSTRUCTOR ABD 100 101 1821 Open 4 TU TH 11:20 AM - 12:50 PM Moody-Freeman,Julie E COURSE TITLE: INTRODUCTION TO AFRICAN AND BLACK DIASPORA STUDIES CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 408 COMBINED SECTION: ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: SSMW ABD 211 101 1638 Open 4 TU 05:45 PM - 09:00 PM Otunnu,Ogenga COURSE TITLE: AFRICA TO 1800: AGE OF EMPIRES CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 207 COMBINED SECTION: HST131 701/ABD 211 ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: UP ABD 229 101 2088 Open 4 MO WE 11:20 AM - 12:50 PM Pierce,Lori COURSE TITLE: RACE, SCIENCE AND WHITE SUPREMACY CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: ARTSLETTER ROOM: 109 COMBINED SECTION: ABD 229/AMS 297/PAX 290 ADDITIONAL NOTES: REQ DESIGNATION: SSMW ABD 236 101 6821 Open 4 TU TH 01:00 PM - 02:30 PM COURSE TITLE: BLACK FREEDOM MOVEMENTS CLASS TYPE: Enrollment Section CONSENT: No Special Consent Required LOCATION: Lincoln Park Campus BUILDING: LEVAN ROOM: -

Angela Jackson

This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. ANGELA JACKSON A renowned Chicago poet, novelist, play- wright, and biographer, Angela Jackson published her first book while still a stu- dent at Northwestern University. Though Jackson has achieved acclaim in multi- ple genres, and plans in the near future to add short stories and memoir to her oeuvre, she first and foremost considers herself a poet. The Poetry Foundation website notes that “Jackson’s free verse poems weave myth and life experience, conversation, and invocation.” She is also renown for her passionate and skilled Photo by Toya Werner-Martin public poetry readings. Born on July 25, 1951, in Greenville, Mississippi, Jackson moved with her fam- ily to Chicago’s South Side at the age of one. Jackson’s father, George Jackson, Sr., and mother, Angeline Robinson, raised nine children, of which Angela was the middle child. Jackson did her primary education at St. Anne’s Catholic School and her high school work at Loretto Academy, where she earned a pre-medicine scholar- ship to Northwestern University. Jackson switched majors and graduated with a B.A. in English and American Literature from Northwestern University in 1977. She later earned her M.A. in Latin American and Caribbean studies from the University of Chicago, and, more recently, received an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Bennington College. While at Northwestern, Jackson joined the Organization for Black American Culture (OBAC), where she matured under the guidance of legendary literary figures such as Hoyt W Fuller. -

Pynchon in Popular Magazines John K

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar English Faculty Research English 7-1-2003 Pynchon in Popular Magazines John K. Young Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/english_faculty Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Young, John K. “Pynchon in Popular Magazines.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 44.4 (2003): 389-404. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pynchon in Popular Magazines JOHN K. YOUNG Any devoted Pynchon reader knows that "The Secret Integration" originally appeared in The Saturday Evening Post and that portions of The Crying of Lot 49 were first serialized in Esquire and Cavalier. But few readers stop to ask what it meant for Pynchon, already a reclusive figure, to publish in these popular magazines during the mid-1960s, or how we might understand these texts today after taking into account their original sites of publica- tion. "The Secret Integration" in the Post or the excerpt of Lot 49 in Esquire produce different meanings in these different contexts, meanings that disappear when reading the later versions alone. In this essay I argue that only by studying these stories within their full textual history can we understand Pynchon's place within popular media and his responses to the consumer culture through which he developed his initial authorial image. -

Nelson Algren Accuse Playboy Frédéric DUMAS

Éros est mort à Chicago : Nelson Algren accuse Playboy Frédéric DUMAS Nelson Algren fut Lauréat du premier National Book Award en 1950 pour The Man with the Golden Arm, dont l’adaptation cinématographique par Otto Preminger eut un immense succès (avec, dans les rôles principaux, Frank Sinatra et Kim Novak). Malgré son talent d’écrivain, il reste avant tout célèbre pour sa relation amoureuse avec Simone de Beauvoir. À la suite de la publication de Lettres à Nelson Algren, il y a quatre ans, la BBC, les télévisions américaine et française ont diffusé plusieurs émissions, consacrées à cette relation, qui a profondément marqué les œuvres respectives des deux auteurs. Sur le plan anecdotique, l’évocation d’Algren dans le cadre de ce colloque est d’autant plus justifiée, qu’Algren est définitivement rentré dans l’histoire pour avoir donné à Simone de Beauvoir son premier orgasme ! Entre 1935 et 1981, date de sa mort, il a publié neuf ouvrages : des romans, un long poème en prose, un recueil de nouvelles toujours populaire (The Neon Wilderness) et quelques ouvrages inclassables, mêlant entre autres les récits de voyages, la poésie, la nouvelle et le récit auto- biographique. Pour Algren, les relations sociales sont devenues vides de sens en raison de la toute puissance du monde des affaires et de son conformisme, incapables de donner un sens à l’existence. Le “business” propose une seule façon d’appréhender la vie, exempte de tous les aléas inhérents aux affres des sentiments ou des plaisirs naturels : ils seraient susceptibles de mettre en danger le confort de l’individu, et par conséquent, indirectement, la pérennité du système.