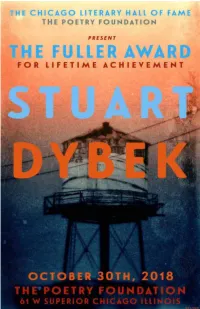

FULLER AWARD for LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT 1 CONTENTS Tonight’S Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fools Crow, James Welch

by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Office of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov Cover: #955-523, Putting up Tepee poles, Blackfeet Indians [no date]; Photograph courtesy of the Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena, MT. by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Ofce of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov #X1937.01.03, Elk Head Kills a Buffalo Horse Stolen From the Whites, Graphite on paper, 1883-1885; digital image courtesy of the Montana Historical Society, Helena, MT. Anchor Text Welch, James. Fools Crow. New York: Viking/Penguin, 1986. Highly Recommended Teacher Companion Text Goebel, Bruce A. Reading Native American Literature: A Teacher’s Guide. National Council of Teachers of English, 2004. Fast Facts Genre Historical Fiction Suggested Grade Level Grades 9-12 Tribes Blackfeet (Pikuni), Crow Place North and South-central Montana territory Time 1869-1870 Overview Length of Time: To make full use of accompanying non-fiction texts and opportunities for activities that meet the Common Core Standards, Fools Crow is best taught as a four-to-five week English unit—and history if possible-- with Title I support for students who have difficulty reading. Teaching and Learning Objectives: Through reading Fools Crow and participating in this unit, students can develop lasting understandings such as these: a. -

Interviewing Sandra Cisneros: Living on the Frontera*

INTERVIEWING SANDRA CISNEROS: LIVING ON THE FRONTERA* Pilar Godayol Nogue Sandra Cisneros is the most powerful representative of the group of young Chicana writers who emerged in the 19805. Her social and political involvement is considerably different from that of Anaya and Hinojosa, the first generation of Chicano writers writing in English. She has a great ability to capture a multitude of voices in her fiction. Although she was trained as a poet, her greatest talents lie in storytelling when she becomes a writer of fiction. Sandra Cisneros was bom in Chicago in 1954. Her first book of fiction, The House on Mango Street (1984), is about growing up in a Latino neighbourhood in Chicago. Her second book of short stories, Woman Hollering Creek (1991), confinns her stature as a writer of great talent. She has also published two books of poetry, My WICked Wicked Ways (1987) and Loose Woman (1994). My interest in her work sprang from her mixing two languages, sometimes using the syntax of one language with the vocabulary of another, at other times translating literally Spanish phrases or words into English, or even including Spanish words in the English text. This fudging of the roles of writer and translator reflects the world she describes in her novels where basic questions of identity and reality are explored. Pilar Godayol. Your work includes mixed-language use. How do you choose when to write a particular word in English or Spanish? Sandra Cisneros. I'm always aware when I write something in English, if it sounds chistoso. I'm aware when someone is saying something in English, or when I am saying something, of how interesting it sounds if I translate it. -

L E S B I a N / G

LESBIAN/GAY L AW JanuaryN 2012 O T E S 03 11th Circuit 10 Maine Supreme 17 New Jersey Transgender Ruling Judicial Court Superior Court Equal Protection Workplace Gestational Discrimination Surrogacy 05 Obama Administration 11 Florida Court 20 California Court Global LGBT Rights of Appeals of Appeal Parental Rights Non-Adoptive 06 11th Circuit First Same-Sex Co-Parents Amendment Ruling 14 California Anti-Gay Appellate Court 21 Texas U.S. Distict Counseling Non-Consensual Court Ruling Oral Copulation High School 09 6th Circuit “Outing” Case Lawrence- 16 Connecticut Based Challenge Appellate Ruling Incest Conviction Loss of Consortium © Lesbian/Gay Law Notes & the Lesbian/Gay Law Notes Podcast are Publications of the LeGaL Foundation. LESBIAN/GAY DEPARTMENTS 22 Federal Civil Litigation Notes L AW N O T E S 25 Federal Criminal Litigation Editor-in-Chief Notes Prof. Arthur S. Leonard New York Law School 25 State Criminal Litigation 185 W. Broadway Notes New York, NY 10013 (212) 431-2156 | [email protected] 26 State Civil Litigation Notes Contributors 28 Legislative Notes Bryan Johnson, Esq. Brad Snyder, Esq. 30 Law & Society Notes Stephen E. Woods, Esq. Eric Wursthorn, Esq. 33 International Notes New York, NY 36 HIV/AIDS Legal & Policy Kelly Garner Notes NYLS ‘12 37 Publications Noted Art Director Bacilio Mendez II, MLIS Law Notes welcomes contributions. To ex- NYLS ‘14 plore the possibility of being a contributor please contact [email protected]. Circulation Rate Inquiries LeGaL Foundation 799 Broadway Suite 340 New York, NY 10003 THIS MONTHLY PUBLICATION IS EDITED AND (212) 353-9118 | [email protected] CHIEFLY WRIttEN BY PROFESSOR ARTHUR LEONARD OF NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL, Law Notes Archive WITH A STAFF OF VOLUNTEER WRITERS http://www.nyls.edu/jac CONSISTING OF LAWYERS, LAW SCHOOL GRADUATES, AND CURRENT LAW STUDENTS. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

Sangamon State University a Springfield, IL 62708

s~'$$$ Sangamon State University a Springfield, IL 62708 Volume 3, Number 1 Office of University Relations August 28,1986 PAC 569 786-6716 CONVOCOM To Air Soccer Game Welcome The SSU TV Office will tape coverage of The SSU WEEKLY staff extends greetings to the Prairie StarsIQuincy College soccer game all new and returning students, faculty and on Friday, September 5, at Quincy for later staff at the beginning of this fall semester. broadcast on CONVOCOM. The game will air on The WEEKLY contains stories about faculty, three CONVOCOM channels, WJPT in Jackson- staff and studqnts and various University ville, WQEC in Quincy and WIUM-TV in Macomb, events and activities. beginning at 8:30 p.m. on Friday, September Please send news items to your program 5, and 8 p.m. on Saturday, September 6 (The coordinator or unit administrator to be game actually begins at 7 p.m. on Sep- submitted to SSU WEEKLY, PAC 569, by the tember 5). Springfield area residents will Monday prior to the publication date. The be able to see the game on WJPT, cable WEEKLY is printed every Thursday. If you channel 23. have any questions regarding the SSU WEEKLY, The game is part of a four-team call 786-6716. tournament. Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville will play the Air Force Academy Reminders at 5 p.m. on September 5. *The University will be closed Monday, Amnesty Program September 1, for the observance of Labor Day. The University will be open Tuesday, In an effort to reduce the number and September 2, but no classes are scheduled. -

Joy Harjo Reads from 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library

Joy Harjo Reads From 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library [0:00:05] Podcast Announcer: Welcome to the Seattle Public Library's podcasts of author readings and Library events; a series of readings, performances, lectures and discussions. Library podcasts are brought to you by the Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts visit our website at www.spl.org. To learn how you can help the Library Foundation support the Seattle Public Library go to foundation.spl.org. [0:00:40] Marion Scichilone: Thank you for joining us for an evening with Joy Harjo who is here with her new book Crazy Brave. Thank you to Elliot Bay Book Company for inviting us to co-present this event, to the Seattle Times for generous promotional support for library programs. We thank our authors series sponsor Gary Kunis. Now, I'm going to turn the podium over to Karen Maeda Allman from Elliott Bay Book Company to introduce our special guest. Thank you. [0:01:22] Karen Maeda Allman: Thanks Marion. And thank you all for coming this evening. I know this is one of the readings I've most look forward to this summer. And as I know many of you and I know that many of you have been reading Joy Harjo's poetry for many many years. And, so is exciting to finally, not only get to hear her read, but also to hear her play her music. Joy Harjo is of Muscogee Creek and also a Cherokee descent. And she is a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop at the University of Iowa. -

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

Burris, Durbin Call for DADT Repeal by Chuck Colbert Page 14 Momentum to Lift the U.S

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Mar. 10, 2010 • vol 25 no 23 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Burris, Durbin call for DADT repeal BY CHUCK COLBERT page 14 Momentum to lift the U.S. military’s ban on Suzanne openly gay service members got yet another boost last week, this time from top Illinois Dem- Marriage in D.C. Westenhoefer ocrats. Senators Roland W. Burris and Richard J. Durbin signed on as co-sponsors of Sen. Joe Lie- berman’s, I-Conn., bill—the Military Readiness Enhancement Act—calling for and end to the 17-year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. Specifically, the bill would bar sexual orien- tation discrimination on current service mem- bers and future recruits. The measure also bans armed forces’ discharges based on sexual ori- entation from the date the law is enacted, at the same time the bill stipulates that soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guard members previ- ously discharged under the policy be eligible for re-enlistment. “For too long, gay and lesbian service members have been forced to conceal their sexual orien- tation in order to dutifully serve their country,” Burris said March 3. Chicago “With this bill, we will end this discrimina- Takes Off page 16 tory policy that grossly undermines the strength of our fighting men and women at home and abroad.” Repealing DADT, he went on to say in page 4 a press statement, will enable service members to serve “openly and proudly without the threat Turn to page 6 A couple celebrates getting a marriage license in Washington, D.C. -

Fulbright Scholars Directory

FULBRIG HT SCHOLAR PROGRAM 2002-2003 Visiting Scholar Directory Directory of Visiting Fulbright Scholars and Occasional Lecturers V i s i t i n g F u l b r i g h t S c h o l a r P r o g r a m S t a f f To obtain U.S. contact information fo r a scholar listed in this directory, pleaseC IE S speaks ta ff member with the responsible fo r the scholar s home country. A fr ic a (S ub -S aharan ) T he M id d le E ast, N orth A frica and S outh A sia Debra Egan,Assistant Director Tracy Morrison,Senior Program Coordinator 202.686.6230 [email protected] 202.686.4013 [email protected] M ichelle Grant,Senior Program Coordinator Amy Rustic,Program Associate 202.686.4029 [email protected] 202.686.4022 [email protected] W estern H emisphere E ast A sia and the P acific Carol Robles,Senior Program Officer Susan McPeek,Senior Program Coordinator 202.686.6238 [email protected] 202.686.4020 [email protected] U.S.-Korea International Education Administrators ProgramMichelle Grant,Senior Program Coordinator 202.686.4029 [email protected] Am elia Saunders,Senior Program Associate 202.686.6233 [email protected] S pecial P rograms E urope and the N ew I ndependent S tates Micaela S. Iovine,Senior Program Officer 202.686.6253 [email protected] Sone Loh,Senior Program Coordinator New Century Scholars Program 202.686.4011 [email protected] Dana Hamilton,Senior Program Associate Erika Schmierer,Program Associate 202.686.6252 [email protected] 202.686.6255 [email protected] New Century Scholars -

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

2015 Review from the Director

2015 REVIEW From the Director I am often asked, “Where is the Center going?” Looking of our Smithsonian Capital Campaign goal of $4 million, forward to 2016, I am happy to share in the following and we plan to build on our cultural sustainability and pages several accomplishments from the past year that fundraising efforts in 2016. illustrate where we’re headed next. This year we invested in strengthening our research and At the top of my list of priorities for 2016 is strengthening outreach by publishing an astonishing 56 pieces, growing our two signatures programs, the Smithsonian Folklife our reputation for serious scholarship and expanding Festival and Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. For the our audience. We plan to expand on this work by hiring Festival, we are transitioning to a new funding model a curator with expertise in digital and emerging media and reorganizing to ensure the event enters its fiftieth and Latino culture in 2016. We also improved care for our anniversary year on a solid foundation. We embarked on collections by hiring two new staff archivists and stabilizing a search for a new director and curator of Smithsonian access to funds for our Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Folkways as Daniel Sheehy prepares for retirement, Collections. We are investing in deeper public engagement and we look forward to welcoming a new leader to the by embarking on a strategic communications planning Smithsonian’s nonprofit record label this year. While 2015 project, staffing communications work, and expanding our was a year of transition for both programs, I am confident digital offerings. -

Unworking Community in Sandra Cisneros' the House on Mango Street

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, nº 18 (2014) Seville, Spain. ISSN 1133-309-X, pp 47-59 “GUIDING A COMMUNITY:” UNWORKING COMMUNITY IN SANDRA CISNEROS’ THE HOUSE ON MANGO STREET GERARDO RODRÍGUEZ SALAS Universidad de Granada [email protected] Received 6th March 2014 Accepted 7th April 2014 KEYWORDS Community; Cisneros; Chicano literature; immanence; transcendence PALABRAS CLAVE Comunidad; Cisneros; literatura chicana; inmanencia; transcendencia ABSTRACT The present study revises communitarian boundaries in the fiction of Chicana writer Sandra Cisneros. Using the ideas of key figures in post-phenomenological communitarian theory and connecting them with Anzaldúa and Braidotti’s concepts of borderland and nomadism, this essay explores Cisneros’ contrast between operative communities that crave for the immanence of a shared communion and substantiate themselves in essentialist tropes, and inoperative communities that are characterized by transcendence or exposure to alterity. In The House on Mango Street (1984) the figure of the child is the perfect starting point to ‘unwork’ (in Nancy’s terminology) concepts such as spatial belonging, nationalistic beliefs, linguistic constrictions, and gender roles through a selection of tangible imagery which, from a female child’s pseudo-innocent perspective, aims to generate an inoperative community beyond essentialist tropes, where individualistic and communal drives are ambiguously intertwined. Using Cisneros’ debut novel as a case study, this article studies the female narrator as embodying both