Intestinal Parasite Prevalence in an Area of Ethiopia After Implementing the SAFE Strategy, Enhanced Outreach Services, and Health Extension Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12037347 01.Pdf

PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the preparatory survey on “the Project for Construction of Secondary Schools in Amhara Region in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia” and entrust the said survey to Mohri, Architect & Associates, Inc. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Ethiopia, and conducted field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of Ethiopia for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. July, 2011 Nobuko Kayashima Director General, Human Development Department Japan International Cooperation Agency Summary 1. Outline of the Country The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (hereinafter referred to as “Ethiopia”) is a republic of 1.104 million km2 with a population of approximately 82.82 million (World Bank, 2009). Its population is the second largest amongst Sub-Sahara African nations. It is an in-land country bordered by Somalia on the east, by Sudan on the west, by Kenya on the south, by Eritrea on the north and also by Djibouti on the southeast. The Ethiopian Highland and other plateaus occupy the majority of the land, and those vary from 1,500 to 4,000 m above sea level. Ethiopia belongs to the tropical region however, the climate differs from one place to another. Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, is located at 2,400 m above sea level, and the average annual temperature is 16C. -

NATIONAL METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AGENCY TEN DAY AGROMETEOROLOGICAL BULLETIN P.BOX 1090 ADDIS ABABA TEL 512299 FAX 517066 E-Mail [email protected]

NATIONAL METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AGENCY TEN DAY AGROMETEOROLOGICAL BULLETIN P.BOX 1090 ADDIS ABABA TEL 512299 FAX 517066 E-mail [email protected] 11-20, July 2004 Volume 14 No. 20 Date of issue: July 23, 2004 SUMMARY During the first dekad of July 2004, the observed normal to above normal rainfall over most parts of western Tigray, Amhara, Benishangul Gumuz, parts of western Oromiya, Gambela and northwestern SNNPR favoured season’s agricultural activities while the reverse was true in some areas eastern Tigray, Amhara and eastern Oromiya including most parts of SNNPR. For instance, Kombolcha, Mieso and Dolomena reported slight wilting and partial drying on sorghum and maize fields due to water stress. On the contrary, some areas of western Amhara, western and central Oromiya including central Tigray and northern Benishangul Gumuz received heavy falls ranging from 30 – 74 mm. During the Second dekad of July 2004, the observed normal to above normal rainfall over most parts of Kiremt benefiting areas favored season's agricultural activities. As a result the general field condition of the crop was in a good shape in most parts of the reporting stations. Moreover, sowing of wheat, teff and pulse crops was underway in some areas of central and western Oromiya, northern SNNPR and eastern Amhara. However some pocket areas of western and eastern lowlands were still under deficient condition. On the other hand some areas of central, eastern and southern highlands exhibited falls greater than 30 mm. For instance Bahir Dar, Senkata, Debre Markos, Kachisie, Debre Birhan, Wegel Tena, Limu Genet and Kombolcha recorded 95.5, 68.2, 58.3, 55.7, 45.6, 44.6, 42.6 and 40.6 mm of heavy fall in one rainy day, respectively. -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

The Socioecological Significance of Dispersed Farmland Trees in Northern Ethiopia

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Honors Theses Student Research 2016 Missing the Trees for the Forest: The Socioecological Significance of Dispersed Farmland Trees in Northern Ethiopia Jacob A. Wall Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, Geographic Information Sciences Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, Remote Sensing Commons, Spatial Science Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Wall, Jacob A., "Missing the Trees for the Forest: The Socioecological Significance of Dispersed Farmland Trees in Northern Ethiopia" (2016). Honors Theses. Paper 950. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/950 This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Missing the Trees for the Forest: The Socioecological Significance of Dispersed Farmland Trees in Northern Ethiopia Jacob A. Wall Environmental Studies Program Colby College Waterville, Maine May 16, 2016 A thesis submitted to the faculty of the Environmental Studies Program in partial fulfillment of the graduation requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors in Environmental Studies. ________________________ _______________________ ____________________ Travis W. Reynolds, Advisor Manny Gimond, Reader Bruce Rueger, Reader i Copyright © 2016 by the Environmental Studies Program, Colby College. -

Final Report1

PROJECT REPORT To: Austrian Development Agency NGO Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid Zelinkagasse 2, 1010 Vienna E-mail: [email protected] Project progress reports are to be presented by e-mail as contractually agreed. Originals of additional documents can be sent to the NGO Cooperation desk. Final Report1 Contract number: 2679-00/2016 Contract partner in Austria Local project partner Name: Name: CARE Österreich CARE Ethiopia Address: Address: Lange Gasse 30/4, 1080 Vienna, Austria Telephone, e-mail: Telephone, e-mail: +43 1 715 0 715 +251 911 237 582 [email protected] +251911819687 Project officer/contact: Project officer/contact: Stéphanie Bouriel Teyent Taddesse [email protected] [email protected] Worku Abebaw [email protected] Project title: Emergency Seed Support to Smallholder Drought- Affected Farmers in South Gondar Ethiopia Country: Ethiopia Region/place: Amhara /South Gondar Duration from: 29 Feb 2016 to: 30 November 2016 Report as at (date):November 30, 2016 submitted on: March 7, 2017 Invoicing as at (date) in euros Submitted for Total project costs Invoiced to date Outstanding verification as at (date) 430,000 EURO 424,598.14 EURO 424.598,14 EURO 5.401,86 Date, report written by CARE Ethiopia, February 2017 1 Delete as applicable NGO individual projects– version: January 2009 | 1 PROJECT REPORT 1. Brief description of project progress2 (German, max. 1 page) A drought due to the effect of El Niño phenomenon had impacted 10.2 million people in various regions of Ethiopia. South Gonder administrative zone located in Amhara region and comprising seven livelihood zones, was amongst the areas most affected. -

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 and Reassessment of Crop

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 And Reassessment Of Crop Production and Marketing For 2014/15 October 2015 Final Report Ethiopia: Bellmon Analysis - 2014/15 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Economic Background ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Poverty ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Wage Labor ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Agriculture Sector Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

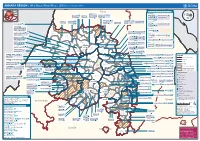

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Rice Value Chain Development in Fogera Woreda Based on the IPMS Experience

Rice value chain development in Fogera woreda based on the IPMS experience Tilahun Gebey, Kahsay Berhe, Dirk Hoekstra and Bogale Alemu March 2012 Canadian International Agence canadienne de Development Agency développement international ILRI works with partners worldwide to help poor people keep their farm animals alive and productive, increase and sustain their livestock and farm productivity, and find profitable markets for their animal products. ILRI’s headquarters are in Nairobi, Kenya; we have a principal campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and 14 offices in other regions of Africa and Asia. ILRI is part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (www.cgiar.org), which works to reduce hunger, poverty and environmental degradation in developing countries by generating and sharing relevant agricultural knowledge, technologies and policies. © 2012 International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) This publication is copyrighted by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). It is licensed for use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. Unless otherwise noted, you are free to copy, duplicate, or reproduce, and distribute, display, or transmit any part of this publication or portions thereof without permission, and to make translations, adaptations, or other derivative works under the following conditions: ATTRIBUTION. The work must be attributed, but not in any way that suggests endorsement by ILRI or the author(s) NON-COMMERCIAL. This work may not be used for commercial purposes. SHARE ALIKE. If this work is altered, transformed, or built upon, the resulting work must be distributed only under the same or similar license to this one. -

English-Full (0.5

Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Building Climate Resilient Green Economy in Ethiopia Strategy for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations Wubalem Tadesse Alemu Gezahegne Teshome Tesema Bitew Shibabaw Berihun Tefera Habtemariam Kassa Center for International Forestry Research Ethiopia Office Addis Ababa October 2015 Copyright © Center for International Forestry Research, 2015 Cover photo by authors FOREWORD This regional strategy document for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State, with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations, was produced as one of the outputs of a project entitled “Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy”, and implemented between September 2013 and August 2015. CIFOR and our ministry actively collaborated in the planning and implementation of the project, which involved over 25 senior experts drawn from Federal ministries, regional bureaus, Federal and regional research institutes, and from Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources and other universities. The senior experts were organised into five teams, which set out to identify effective forest management practices, and enabling conditions for scaling them up, with the aim of significantly enhancing the role of forests in building a climate resilient green economy in Ethiopia. The five forest management practices studied were: the establishment and management of area exclosures; the management of plantation forests; Participatory Forest Management (PFM); agroforestry (AF); and the management of dry forests and woodlands. Each team focused on only one of the five forest management practices, and concentrated its study in one regional state. -

Determinants of Smallholder Farmers' Rice Market Participation in Libo Kemekem Woreda, Amhara Region

International Journal of Development in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijdssh.com (IJDSSH) 2019, Vol. No.8, Jul-Dec e-ISSN: 2455-5142; p-ISSN: 2455-7730 DETERMINANTS OF SMALLHOLDER FARMERS’ RICE MARKET PARTICIPATION IN LIBO KEMEKEM WOREDA, AMHARA REGION Endesew Eshetie University of Gondar College of Business and Economics Department of Marketing Management ABSTRACT Cultivation of rice in Ethiopia is generally a recent phenomenon. Rice has become a commodity of strategic significance across many parts of Ethiopia for domestic consumption as well as export market for economic development. This study was conducted in Libo Kemekem Woreda, Amhara Region. The main purpose of this study was to analyze the determinants of smallholder farmers’ participation in rice market. In this study three representative Kebeles were selected using multistage sampling technique. Then, sample household farmers were drawn by random sampling technique. Thus, 215 smallholder rice producer farmers were selected to the study, and through questionnaire and interview data were gathered. The collected data then be analyzed using SPSS and the results were interpreted and presented using descriptive statistics. Hence, the result revealed that 91.2% were male headed households and 8.8% were female headed. The minimum ageof participants were 29 and the maximum age was 70. About 94.9% of respondents were married, 3.3% were divorced, and 1.9% was separated; the major reason for growing rice was mainly for market. The result also identified about 98.1% smallholder farmer heads were members of cooperatives. On the contrary, farmers faced lack of improved seed and fertilizer, fear of crop failure due to unexpected rains and existence of different diseases. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

Good Governance for Achieving Food Security in Ethiopia: Challenges and Issues

57 Good Governance for Achieving Food Security in Ethiopia: Challenges and Issues Mussie Ybabe, Addis Ababa University Sisay Asefa, Western Michigan University Abstract Although rice technologies have been introduced in Fogera district over the last two decades, farm household’s food demand was not met as expected. Sustained, intensified and coordinated rice research is the key to curb the problem but impaired due to lack of good governance coupled with weak institutional capacity. This has resulted snowballing effects like little or no discussion among/with farmers on good practices, successes/failures of technology adoption and input delivery; poor linkage of small farmers to market and knowledge gap in Development Agents. Therefore, this study identified and evaluated potential determinants of household food security with basic emphasis to factors linked to good governance introduced to address the problem of food security in the study area through farm household rice technology adoption. A multistage sampling technique is used to select respondents. To this end, the primary data was gathered from the field survey by administering pre-tested structured and semi-structured questionnaire. Good governance dimensions of food security are evaluated using binary logit model for its comparative mathematical and interpretational simplicity. Farmers’ own perception of rice technology intervention vis-a-vis farm household food security is explored using focus group discussions supplemented by in-depth interviews. This study result would be primarily important in designing policy interventions and good governance strategies ensuring appropriate use of rice technology and tackle food security problems. Key words: Rice technology, logit model, good governance, food security Introduction Ethiopia is one of the most famine-prone countries with a long history of famines and food shortages.