The Intertextuality and Translations of Fine Art and Class in Hip-Hop Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking the Relationship Between Plagiarism and Academic Integrity

Document generated on 09/30/2021 1:32 p.m. Revue internationale des technologies en pédagogie universitaire International Journal of Technologies in Higher Education Rethinking the relationship between plagiarism and academic integrity Repenser la relation entre le plagiat et l’intégrité académique Sandra Jamieson and Rebecca Moore Howard Du plagiat à l’intégrité académique : quelles compétences, quelles Article abstract stratégies? The term academic integrity is in widespread use, and while there has been From plagiarism to academic integrity: Which skills, which much debate about what is included under that term and how we measure and strategies? encourage integrity in an academic context, no specific definition has been Volume 16, Number 2, 2019 codified and universally accepted. This article reviews the historical evolution of the phrase through scholarship beginning in the 1960s, its shifting definition URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1067061ar as an ethical or moral concept, and the ways in which it is currently being used, with a focus on the logics by which textual errors came to be classified as moral lapses. This article also provides analysis of students’ textual errors as See table of contents they work from sources. Based on these analyses, we advocate bringing together all cheating behaviors, including academic ghostwriting, under the umbrella of academic integrity and calling them cheating, plain and simple. At Publisher(s) the same time, we contend that textual errors such as patchwriting and faulty citation should be removed from the moral category of academic integrity and CRIFPE treated as instances of bad writing to be remedied by pedagogy, not punishment. -

Sexism Across Musical Genres: a Comparison

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 6-24-2014 Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison Sarah Neff Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Neff, Sarah, "Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison" (2014). Honors Theses. 2484. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2484 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: SEXISM ACROSS MUSICAL GENRES 1 Sexism Across Musical Genres: A Comparison Sarah E. Neff Western Michigan University SEXISM ACROSS MUSICAL GENRES 2 Abstract Music is a part of daily life for most people, leading the messages within music to permeate people’s consciousness. This is concerning when the messages in music follow discriminatory themes such as sexism or racism. Sexism in music is becoming well documented, but some genres are scrutinized more heavily than others. Rap and hip-hop get much more attention in popular media for being sexist than do genres such as country and rock. My goal was to show whether or not genres such as country and rock are as sexist as rap and hip-hop. In this project, I analyze the top ten songs of 2013 from six genres looking for five themes of sexism. The six genres used are rap, hip-hop, country, rock, alternative, and dance. -

The Influence of Rap in the Arab Spring

Augsburg Honors Review Volume 6 Article 12 2013 The Influence of apr in the Arab Spring Samantha Cantrall Augsburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://idun.augsburg.edu/honors_review Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Cantrall, Samantha (2013) "The Influence of apr in the Arab Spring," Augsburg Honors Review: Vol. 6 , Article 12. Available at: https://idun.augsburg.edu/honors_review/vol6/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Idun. It has been accepted for inclusion in Augsburg Honors Review by an authorized editor of Idun. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IruFLUENCE oF RAP IN THE AnAB SPRING ey SaHaANTHA Carurneu-AuGSBURc CollEGE Enculry Anvrson: Dn. Roeenr Srecrcr BSTRACT: Throughout history, music has been influential in social, reli- gious, and political disputes. In the early 21st century, change in the estab- order can be found in expressing the need for reform halfway around the world in the Middle East's Arab Spring. Rap artists such as El General (Tunisia), GAB (Libya), and Omar Offendum (Syria) used their talents to both spark and en- courage protestors during the early days of the Middle Eastern protests that began in late 2010; these protests have since been coined "The Arab Spring." The energy that could have been used to wield guns and bombs was instead poured into protest music that these and other artists produced during this time period. The relatively Western genre of rap music became integral in peaceful citizens protests happening all over the Middle East. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Translating Ironic Intertextual Allusions.” In: Martínez Sierra, Juan José & Patrick Zabalbeascoa Terran (Eds.) 2017

Recibido / Received: 30/06/2016 Aceptado / Accepted: 16/11/2016 Para enlazar con este artículo / To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/MonTI.2017.9.5 Para citar este artículo / To cite this article: LIEVOIS, Katrien. (2017) “Translating ironic intertextual allusions.” In: Martínez Sierra, Juan José & Patrick Zabalbeascoa Terran (eds.) 2017. The Translation of Humour / La traducción del humor. MonTI 9, pp. 1-24. TRANSLATING IRONIC INTERTEXTUAL ALLUSIONS Katrien Lievois [email protected] Université d’Anvers Translated from French by Trish Van Bolderen1 [email protected] University of Ottawa Abstract Based on a corpus consisting of Albert Camus’s La Chute, Hugo Claus’s Le chagrin des Belges, Fouad Laroui’s Une année chez les Français and their Dutch versions, this article examines the ways in which ironic intertextual allusions are translated. It begins with a presentation of the theoretical concepts underpinning the analysis and subsequently identifies, through a detailed study, the following nine strategies: standard translation; literal translation; translation using markers; non-translation; translation into a third language; glosses; omissions; substitutions using intertextuality from the target culture; and substitutions using architextuality. Resume A partir d’un corpus constitué de La Chute d’Albert Camus, du Chagrin des Belges de Hugo Claus et d’Une année chez les Français de Fouad Laroui, ainsi que leurs versions néerlandaises, cette contribution s’intéresse à la traduction de l’allusion intertextuelle ironique. Elle présente d’abord les concepts théoriques qui sous-tendent l’analyse, pour ensuite étudier plus en détail les 9 stratégies rencontrées : la traduction standard, la traduction littérale, la traduction avec marquage, la non-traduction, la traduction primera 1. -

Rapping the Arab Spring

Rapping the Arab Spring SAM R. KIMBALL UNIS—Along a dusty main avenue, past worn freight cars piled on railroad tracks and Tyoung men smoking at sidewalk cafés beside shuttered shops, lies Kasserine, a town unremarkable in its poverty. Tucked deep in the Tunisian interior, Kasserine is 200 miles from the capital, in a region where decades of neglect by Tunisia’s rulers has led ANE H to a state of perennial despair. But pass a prison on the edge of town, and a jarring mix of neon hues leap from its outer wall. During the 2011 uprising against former President Zine El-Abdine Ben Ali, EM BEN ROMD H prisoners rioted, and much of the wall was destroyed HIC in fighting with security forces. On the wall that re- 79 Downloaded from wpj.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on December 16, 2014 REPORTAGE mains, a poem by Tunisian poet Abu al in it for fame. But one thing is certain— Qassem Chebbi stretches across 800 feet the rebellions that shook the Arab world of concrete and barbed wire, scrawled in tore open a space for hip-hop in politics, calligraffiti—a style fusing Arabic callig- destroying the wall of fear around freedom raphy with hip hop graffiti—by Tunisian of expression. And governments across the artist Karim Jabbari. On each section of region are now watching hip-hop’s advance the wall, one elaborate pattern merges into with a blend of contempt and dread. a wildly different one. “Before Karim, you might have come to Kasserine and thought, PRE-ARAB SPRING ‘There’s nothing in this town.’ But we’ve “Before the outbreak of the Arab Spring, got everything—from graffiti, to break- there was less diversity,” says independent dance, to rap. -

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

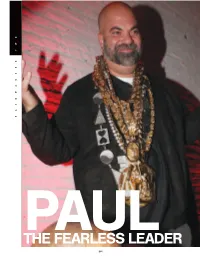

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

DJ Skills the Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3

The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 1 74 The Rise of The Hip-hop DJ DJs were Hip-hop’s original architects, and remain crucial to its contin- ued development. Hip-hop is more than a style of music; it’s a culture. As with any culture, there are various artistic expressions of Hip-hop, the four principal expressions being: • visual art (graffiti) • dance (breaking, rocking, locking, and popping, collectively known in the media as “break dancing”) • literature (rap lyrics and slam poetry) • music (DJing and turntablism) Unlike the European Renaissance or the Ming Dynasty, Hip-hop is a culture that is very much alive and still evolving. Some argue that Hip-hop is the most influential cultural movement in history, point- ing to the globalization of Hip-hop music, fashion, and other forms of expression. Style has always been at the forefront of Hip-hop. Improvisation is called free styling, whether in rap, turntablism, breaking, or graf- fiti writing. Since everyone is using the essentially same tools (spray paint for graffiti writers, microphones for rappers and beat boxers, their bodies for dancers, and two turntables with a mixer for DJs), it’s the artists’ personal styles that set them apart. It’s no coincidence that two of the most authentic movies about the genesis of the move- ment are titled Wild Style and Style Wars. There are also many styles of writing the word “Hip-hop.” The mainstream media most often oscillates between “hip-hop” and “hip hop.” The Hiphop Archive at Harvard writes “Hiphop” as one word, 2 DJ Skills The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3 with a capital H, embracing KRS-ONE’s line of reasoning that “Hiphop Kool DJ Herc is a culture with its own foundation narrative, history, natives, and 7 In 1955 in Jamaica, a young woman from the parish of Saint Mary mission.” After a great deal of input from many people in the Hip-hop community, I’ve decided to capitalize the word but keep the hyphen, gave birth to a son who would become the father of Hip-hop. -

Affective Temporalities in Gob Squad’S Kitchen (You’Ve Never Had It So Good)

56 ANA PAIS AFFECTIVE TEMPORALITIES IN GOB SQUAD’S KITCHEN (YOU’VE NEVER HAD IT SO GOOD) In this article I will be drawing upon affect theory to unpack issues of authenticity, mediation, participation in the production Gob Squads’s Kitchen, by Gob Squad. English/German collective reconstructed Andy Warhol’s early film Kitchen, shot 47 years before, in the flamboyant Factory, starring ephemeral celebrities such as Eve Sedgwick. Alongside Eat (1964), Sleep (1963) and Screen Test (1964-66). Although it premièred in Berlin, in 2007, the show has been touring in several countries and, in 2012, it received the New York Drama Desk Award for Unique Theatrical Experience.I will be examining how the production’s spatial dispositive creates a mediated intimacy that generates affective temporalities and how their performativity allows us to think of the audience as actively engaged in an affective resonance with the stage. Intimacy creates worlds (Berlant 2000). It brings audience and performer closer not only to each other but also to the shifting moment of Performance Art’s capture by institutional discourses and market value. Unleashing affective temporalities allows the audience to embody its potency, to be, again, “at the beginning”.Drawing upon André Lepecki’s notion of reenactments as activations of creative possibilities, I will be suggesting that Gob Squads’s Kitchen merges past and present by disclosing accumulated affects, promises and deceptions attached to the thrilling period of the sixties in order to reperform a possibility of a new beginning at the heart of a nowthen time. In conclusion, this article will shed new light on the performative possibilities of affect to surmount theatrical separation and weave intensive attachments. -

Rapparen & Gourmetkocken Action Bronson Tillbaka Med Nytt Album

2015-03-03 10:31 CET Rapparen & gourmetkocken Action Bronson tillbaka med nytt album Hiphoparen och kocken Arian Asllani, aka Action Bronson, från Queens New York släpper nya albumet Mr. Wonderful den 25 mars. Bronson har med flertalet album, EP’s och mixtapes i ryggen gjort sig ett namn som en utav vår tids bästa rappare. Det sätt han levererar sitt artisteri och kombinerar sina rapfärdigheter med humor, självdistans och genomgående matreferenser gör honom unik i musikvärlden. Innan Bronson påbörjade sin karriär som rappare, som ursprungligen endast var en hobby för honom, var han en respekterad gourmetkock i New York City. Han drev sin egen online matlagnings show med titeln "Action In The Kitchen". Efter att han bröt benet i köket bestämde han sig för att enbart koncentrera sig på musiken. Debutalbumet Dr. Lecter släpptes 2011 såväl som ett par mixtapes, däribland Blue Chips. Sent år 2012 signade rapparen med Warner Music via medieföretaget VICE och för två år sedan släppte han EP’n Saaab Stories samt spelade på en av världens viktigaste musikfestivaler, nämligen Coachella Music Festival. Genom åren har han haft samarbeten med flera stor rappare såsom Wiz Khalifa, Raekwon, Eminem och Kendrick Lamar. Enligt Bronson är det kommande albumet hans bästa verk hittills. “I gave this my most incredible effort,” säger han. “If you listen to everything I’ve put out and then listen to this you’ll hear the steps that I’ve taken to go all out and show progression.” Singeln Baby Blue ft. Chance The Rapper, producerad av Mark Ronson, premiärspelades igår av Zane Lowe på BBC Radio 1. -

SOCIAL DANCE STUDY GUIDE.Pdf

SOCIAL DANCE STUDY GUIDE ELEMENTS OF DANCE 1. Walking- heel first 2. Chasse- step-together-step (ball of foot hits first, then close) 3. Box- combines walking and chasse 4. Rock- transfer weight to one foot, then replace weight to other foot 5. 5th Position Rock Step- As you step back for the rock step, turn the back toe out. This gives you more hip action (rumba, swing) 6. Triple Step- 3 steps to the side (step-together-step) Key: M = man W = woman R = right L = left CCW = counter clock wise FWD = forward BWK = backward Q = quick S = slow DANCE POSITIONS 1. Closed- (foxtrot, waltz, tango) Partners are very close, with the women’s L arm resting on the men’s R, the lead hand is held chin height. 2. Closed- (rumba, cha cha) less arm bend than #1, partners are about 1 foot apart. (swing) lower the lead hand to side 3. One Hand Hold- This is the open position. Hold on same side, M L in W R. 4. R Open- M R side is open and partners are side by side (his L beside her R) 5. L Open- opposite of #4. 6. Promenade- 45-degree angle, both are facing the same direction and are in side- by-side position. 7. Practice- 2-hand hold which allows you to be farther apart. CHA CHA CHA Style- International Latin Meter- 4/4 Tempo- 128 bpm Rhythm- S,S,Q,Q,Q Style- Medium tempo Latin Description- A fun, sexy, flirtatious dance. This is a spot dance using the Cuban motion, which is characteristic of bending and straightening the knees.