Factors That Influence Online Database Use 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blockchain Database for a Cyber Security Learning System

Session ETD 475 Blockchain Database for a Cyber Security Learning System Sophia Armstrong Department of Computer Science, College of Engineering and Technology East Carolina University Te-Shun Chou Department of Technology Systems, College of Engineering and Technology East Carolina University John Jones College of Engineering and Technology East Carolina University Abstract Our cyber security learning system involves an interactive environment for students to practice executing different attack and defense techniques relating to cyber security concepts. We intend to use a blockchain database to secure data from this learning system. The data being secured are students’ scores accumulated by successful attacks or defends from the other students’ implementations. As more professionals are departing from traditional relational databases, the enthusiasm around distributed ledger databases is growing, specifically blockchain. With many available platforms applying blockchain structures, it is important to understand how this emerging technology is being used, with the goal of utilizing this technology for our learning system. In order to successfully secure the data and ensure it is tamper resistant, an investigation of blockchain technology use cases must be conducted. In addition, this paper defined the primary characteristics of the emerging distributed ledgers or blockchain technology, to ensure we effectively harness this technology to secure our data. Moreover, we explored using a blockchain database for our data. 1. Introduction New buzz words are constantly surfacing in the ever evolving field of computer science, so it is critical to distinguish the difference between temporary fads and new evolutionary technology. Blockchain is one of the newest and most developmental technologies currently drawing interest. -

An Introduction to Cloud Databases a Guide for Administrators

Compliments of An Introduction to Cloud Databases A Guide for Administrators Wendy Neu, Vlad Vlasceanu, Andy Oram & Sam Alapati REPORT Break free from old guard databases AWS provides the broadest selection of purpose-built databases allowing you to save, grow, and innovate faster Enterprise scale at 3-5x the performance 14+ database engines 1/10th the cost of vs popular alternatives - more than any other commercial databases provider Learn more: aws.amazon.com/databases An Introduction to Cloud Databases A Guide for Administrators Wendy Neu, Vlad Vlasceanu, Andy Oram, and Sam Alapati Beijing Boston Farnham Sebastopol Tokyo An Introduction to Cloud Databases by Wendy A. Neu, Vlad Vlasceanu, Andy Oram, and Sam Alapati Copyright © 2019 O’Reilly Media Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com). For more infor‐ mation, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or [email protected]. Development Editor: Jeff Bleiel Interior Designer: David Futato Acquisitions Editor: Jonathan Hassell Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Production Editor: Katherine Tozer Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest Copyeditor: Octal Publishing, LLC September 2019: First Edition Revision History for the First Edition 2019-08-19: First Release The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. An Introduction to Cloud Databases, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. The views expressed in this work are those of the authors, and do not represent the publisher’s views. -

Middleware-Based Database Replication: the Gaps Between Theory and Practice

Appears in Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD Conference, Vancouver, Canada (June 2008) Middleware-based Database Replication: The Gaps Between Theory and Practice Emmanuel Cecchet George Candea Anastasia Ailamaki EPFL EPFL & Aster Data Systems EPFL & Carnegie Mellon University Lausanne, Switzerland Lausanne, Switzerland Lausanne, Switzerland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT There exist replication “solutions” for every major DBMS, from Oracle RAC™, Streams™ and DataGuard™ to Slony-I for The need for high availability and performance in data Postgres, MySQL replication and cluster, and everything in- management systems has been fueling a long running interest in between. The naïve observer may conclude that such variety of database replication from both academia and industry. However, replication systems indicates a solved problem; the reality, academic groups often attack replication problems in isolation, however, is the exact opposite. Replication still falls short of overlooking the need for completeness in their solutions, while customer expectations, which explains the continued interest in developing new approaches, resulting in a dazzling variety of commercial teams take a holistic approach that often misses offerings. opportunities for fundamental innovation. This has created over time a gap between academic research and industrial practice. Even the “simple” cases are challenging at large scale. We deployed a replication system for a large travel ticket brokering This paper aims to characterize the gap along three axes: system at a Fortune-500 company faced with a workload where performance, availability, and administration. We build on our 95% of transactions were read-only. Still, the 5% write workload own experience developing and deploying replication systems in resulted in thousands of update requests per second, which commercial and academic settings, as well as on a large body of implied that a system using 2-phase-commit, or any other form of prior related work. -

Database Technology for Bioinformatics from Information Retrieval to Knowledge Systems

Database Technology for Bioinformatics From Information Retrieval to Knowledge Systems Luis M. Rocha Complex Systems Modeling CCS3 - Modeling, Algorithms, and Informatics Los Alamos National Laboratory, MS B256 Los Alamos, NM 87545 [email protected] or [email protected] 1 Molecular Biology Databases 3 Bibliographic databases On-line journals and bibliographic citations – MEDLINE (1971, www.nlm.nih.gov) 3 Factual databases Repositories of Experimental data associated with published articles and that can be used for computerized analysis – Nucleic acid sequences: GenBank (1982, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), EMBL (1982, www.ebi.ac.uk), DDBJ (1984, www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp) – Amino acid sequences: PIR (1968, www-nbrf.georgetown.edu), PRF (1979, www.prf.op.jp), SWISS-PROT (1986, www.expasy.ch) – 3D molecular structure: PDB (1971, www.rcsb.org), CSD (1965, www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk) Lack standardization of data contents 3 Knowledge Bases Intended for automatic inference rather than simple retrieval – Motif libraries: PROSITE (1988, www.expasy.ch/sprot/prosite.html) – Molecular Classifications: SCOP (1994, www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk) – Biochemical Pathways: KEGG (1995, www.genome.ad.jp/kegg) Difference between knowledge and data (semiosis and syntax)?? 2 Growth of sequence and 3D Structure databases Number of Entries 3 Database Technology and Bioinformatics 3 Databases Computerized collection of data for Information Retrieval Shared by many users Stored records are organized with a predefined set of data items (attributes) Managed by a computer program: the database -

What Is a Database? Differences Between the Internet and Library

What is a Database? Library databases are mostly full-text material (in their entirety) and summaries or descriptions of articles. They are collections of articles from newspapers, magazines and journals and electronic reference sources. Databases are selected for the quality and variety of resources they offer and are accessed using the Internet. Your library pays for you to have access to a number of relevant databases. You support this with your tuition, so get the most out of your money! You can access them from home or school via the Library Webpage or use the link below. http://www.mxcc.commnet.edu/Content/Find_Articles.asp Two short videos on the benefits of using library databases: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VUp1P-ubOIc http://youtu.be/Q2GMtIuaNzU Differences Between the Internet and Library Databases The Internet Library Databases Examples Google, Yahoo, Bing LexisNexis, Literary Reference Center or Health and Wellness Resource Center Review process None – anyone can add Checked for accuracy by content to the Web. publishers. Chosen by your college’s library. Includes “peer-reviewed” scholarly articles. Reliability Unknown Very No quality control mechanisms! Content Anything, from pictures of a Scholarly journal articles, Book person’s pets to personal reviews, Research papers, (usually not researched and Conference papers, and other unsubstantiated) opinions on scholarly information gun control, abortion, etc. How often updated Unknown/varies. Regularly – daily, quarterly monthly Cost “Free” but some of the info Library has paid for you to you may need for your access these databases. assignment requires a fee. Organization Very little or no organization Very organized Availability Websites come and go. -

Data Quality Requirements Analysis and Modeling December 1992 TDQM-92-03 Richard Y

Published in the Ninth International Conference of Data Engineering Vienna, Austria, April 1993 Data Quality Requirements Analysis and Modeling December 1992 TDQM-92-03 Richard Y. Wang Henry B. Kon Stuart E. Madnick Total Data Quality Management (TDQM) Research Program Room E53-320 Sloan School of Management Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139 USA 617-253-2656 Fax: 617-253-3321 Acknowledgments: Work reported herein has been supported, in part, by MITís Total Data Quality Management (TDQM) Research Program, MITís International Financial Services Research Center (IFSRC), Fujitsu Personal Systems, Inc. and Bull-HN. The authors wish to thank Gretchen Fisher for helping prepare this manuscript. To Appear in the Ninth International Conference on Data Engineering Vienna, Austria April 1993 Data Quality Requirements Analysis and Modeling Richard Y. Wang Henry B. Kon Stuart E. Madnick Sloan School of Management Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Mass 02139 [email protected] ABSTRACT Data engineering is the modeling and structuring of data in its design, development and use. An ultimate goal of data engineering is to put quality data in the hands of users. Specifying and ensuring the quality of data, however, is an area in data engineering that has received little attention. In this paper we: (1) establish a set of premises, terms, and definitions for data quality management, and (2) develop a step-by-step methodology for defining and documenting data quality parameters important to users. These quality parameters are used to determine quality indicators, to be tagged to data items, about the data manufacturing process such as data source, creation time, and collection method. -

DBOS: a Proposal for a Data-Centric Operating System

DBOS: A Proposal for a Data-Centric Operating System The DBOS Committee∗ [email protected] Abstract Current operating systems are complex systems that were designed before today's computing environments. This makes it difficult for them to meet the scalability, heterogeneity, availability, and security challenges in current cloud and parallel computing environments. To address these problems, we propose a radically new OS design based on data-centric architecture: all operating system state should be represented uniformly as database tables, and operations on this state should be made via queries from otherwise stateless tasks. This design makes it easy to scale and evolve the OS without whole-system refactoring, inspect and debug system state, upgrade components without downtime, manage decisions using machine learning, and implement sophisticated security features. We discuss how a database OS (DBOS) can improve the programmability and performance of many of today's most important applications and propose a plan for the development of a DBOS proof of concept. 1 Introduction Current operating systems have evolved over the last forty years into complex overlapping code bases [70,4, 51, 57], which were architected for very different environments than exist today. The cloud has become a preferred platform, for both decision support and online serving applications. Serverless computing supports the concept of elastic provision of resources, which is very attractive in many environments. Machine learning (ML) is causing many applications to be redesigned, and future operating systems must intimately support such applications. Hardware arXiv:2007.11112v1 [cs.OS] 21 Jul 2020 is becoming massively parallel and heterogeneous. These \sea changes" make it imperative to rethink the architecture of system software, which is the topic of this paper. -

Multimedia Database Support for Digital Libraries

Dagstuhl Seminar 99351 August 29 - September 3 1999 Multimedia Database Support for Digital Libraries E. Bertino (Milano) [email protected] A. Heuer (Rostock) [email protected] T. Ozsu (Alberta) [email protected] G. Saake (Magdeburg) [email protected] Contents 1 Motivation 5 2 Agenda 7 3 Abstracts 11 4 Discussion Group Summaries 24 5 Other Participants 29 4 1 Motivation Digital libraries are a key technology of the coming years allowing the effective use of the Internet for research and personal information. National initiatives for digi- tal libraries have been started in several countries, including the DLI initiative in USA http://www-sal.cs.uiuc.edu/ sharad/cs491/dli.html, Global Info http://www.global- info.org/index.html.en in Germany, and comparable activities in Japan and other Euro- pean countries. A digital library allows the access to huge amounts of documents, where documents themselves have a considerably large size. This requires the use of advanced database technology for building a digital library. Besides text documents, a digital library contains multimedia documents of several kinds, for example audio documents, video sequences, digital maps and animations. All these document classes may have specific retrieval me- thods, storage requirements and Quality of Service parameters for using them in a digital library. The topic of the seminar is the support of such multimedia digital libraries by databa- se technology. This support includes object database technology for managing document structure, imprecise query technologies for example based on fuzzy logic, integration of information retrieval in database management, object-relational databases with multime- dia extensions, meta data management, and distributed storage. -

A Longitudinal Study of Database Usage Within a General Audience Digital Library Abstract 1. Introduction and Literature Revie

A Longitudinal Study of Database Usage Within a General Audience Digital Library Iris Xie & Dietmar Wolfram School of Information Studies University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, P.O. Box 413, Milwaukee, WI 53201, USA Email: {hiris, dwolfram}@uwm.edu Abstract This study reports on a longitudinal investigation of database usage available through BadgerLink, a general audience digital library available to Wisconsin residents in the United States. The authors analyzed BadgerLink database usage, including EBSCO databases sampled every two years over a six-year period between 1999 and 2005 and four years of usage for ProQuest databases between 2002 and 2005. A quantitative analysis of the transaction log summaries was carried out. Available data included database usage, title requests, session usage by institution, format requests (full-text and abstracts), and search feature usage. The results reveal changes in usage patterns, with relative requests for resources in areas such as social sciences and education increasing, and requests for resources in business/finance and leisure/entertainment decreasing. More advanced search feature usage was also observed over time. Relative usage by searchers affiliated with academic institutions has grown dramatically. Longitudinal analysis of database usage presents a picture of dynamic change of resources usage and search interactions over time. The findings of this study are more in line with results from other online database and digital library environments than Web search engine and Web page environments. Keywords: transaction log analysis, longitudinal study, digital libraries, information searching 1. Introduction and Literature Review Transaction log analysis of user interactions with electronic retrieval systems have been undertaken in a variety of environments over the past few decades, and particularly over the past fifteen years with the popularity of Internet-based search services to support information retrieval (IR). -

Edsger Wybe Dijkstra

In Memoriam Edsger Wybe Dijkstra (1930–2002) Contents 0 Early Years 2 1 Mathematical Center, Amsterdam 3 2 Eindhoven University of Technology 6 3 Burroughs Corporation 8 4 Austin and The University of Texas 9 5 Awards and Honors 12 6 Written Works 13 7 Prophet and Sage 14 8 Some Memorable Quotations 16 Edsger Wybe Dijkstra, Professor Emeritus in the Computer Sciences Department at the University of Texas at Austin, died of cancer on 6 August 2002 at his home in Nuenen, the Netherlands. Dijkstra was a towering figure whose scientific contributions permeate major domains of computer science. He was a thinker, scholar, and teacher in renaissance style: working alone or in a close-knit group on problems of long-term importance, writing down his thoughts with exquisite precision, educating students to appreciate the nature of scientific research, and publicly chastising powerful individuals and institutions when he felt scientific integrity was being compromised for economic or political ends. In the words of Professor Sir Tony Hoare, FRS, delivered by him at Dijkstra’s funeral: Edsger is widely recognized as a man who has thought deeply about many deep questions; and among the deepest questions is that of traditional moral philosophy: How is it that a person should live their life? Edsger found his answer to this question early in his life: He decided he would live as an academic scientist, conducting research into a new branch of science, the science of computing. He would lay the foundations that would establish computing as a rigorous scientific discipline; and in his research and in his teaching and in his writing, he would pursue perfection to the exclusion of all other concerns. -

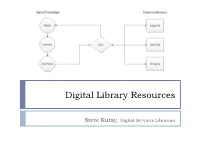

Digital Library Resources

Digital Library Resources Steve Kutay, Digital Services Librarian Digital Resources at the Oviatt Library Collection Formats Interfaces Access Points Main (eBooks) Various proprietary Browser Library Catalog eBrary Reader Select ‘ebooks’ from Blue Fire (EBL) the drop menu Safari To Go (Safari) Virtual Reference Web, PDF Web, PDF Viewers Library Catalog Subscription DBs Journals/Articles Web, PDF Browser Library Catalog PDF Viewers Subscription DBs Gov. Docs Guides Web, Various Browser Library Website Music and Media * Audio, Video, Web, Browser Library Web/Cat Also see Main eBooks PDF, proprietary Subscription DBs * Audio and video recordings in our databases are not currently in our catalog. See Databases: Naxos Music, Traditional Music (LOC), and disciplinary video databases to locate streaming audio and videos. Archives, Manuscripts and Newspapers Collections Formats Interfaces Access Points Oviatt Finding Aids Web, EAD Browser Finding Aid Database (FAD) Online Archive of Web, EAD, PDF Browser, OAC Database California (OAC) PDF Viewers Oviatt Digital Web, JPEG, PDF Browser, Image and Digital Collections Collections Audio PDF Viewers Database Empire Online Web, PDF Browser, Empire Online PDF Viewers Database American Memory JPEG, TIFF Browser, American Memory (Library of Congress) Image Viewers Website Historical Newspapers Web, PDF Browser, Library Website PDF Viewers Subscription DBs CSUN Scholarly Output Collection Formats Interfaces Access Point ScholarWorks Web, PDF Browser, Library Website, PDF Viewers ScholarWorks Website ScholarWorks is: . the institutional repository of CSUN for scholarly output . Open Access (some restrictions may apply) . arranged by departments called ‘Communities’ . a secure solution for the preservation and dissemination of faculty works Contents: . Pre-prints and post-prints . Data sets . Learning objects and tools . -

Oracle Database Upgrade: Quick Start Guide

Oracle Database Upgrade: Quick Start Guide A quick reference to a successful Oracle Database upgrade Feb 20, 2020 | Version 1.01 Copyright © 2020, Oracle and/or its affiliates Public PURPOSE STATEMENT This document provides a quick guide to the steps, tools, and techniques that will ensure a successful upgrade for your Oracle database. This means an upgrade that not only completes without errors, but that delivers a post-upgrade environment with predictable, good performance. DISCLAIMER This document in any form, software or printed matter, contains proprietary information that is the exclusive property of Oracle. Your access to and use of this confidential material is subject to the terms and conditions of your Oracle software license and service agreement, which has been executed and with which you agree to comply. This document and information contained herein may not be disclosed, copied, reproduced or distributed to anyone outside Oracle without prior written consent of Oracle. This document is not part of your license agreement nor can it be incorporated into any contractual agreement with Oracle or its subsidiaries or affiliates. This document is for informational purposes only and is intended solely to assist you in planning for the implementation and upgrade of the product features described. It is not a commitment to deliver any material, code, or functionality, and should not be relied upon in making purchasing decisions. The development, release, and timing of any features or functionality described in this document remains at the sole discretion of Oracle. Due to the nature of the product architecture, it may not be possible to safely include all features described in this document without risking significant destabilization of the code.