“The Inhabitants of the Deep:” Water and the Material Imagination of Blackness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction of Marlou Carlson, by Roxy Jacobs

Plummer Lecture Given to Illinois Yearly Meeting, Seventh Month 2001 Marlou Carlson Introduction of Marlou Carlson, by Roxy Jacobs Most Friends know that Marlou and I share a friendship that we have carefully tended for approximately 20 years. Though arriving by separate paths, we both came to Duneland Friends Meeting at approximately the same time. It was in this context that I came to know Marlou Carlson as a woman who was favored by God with many gifts, and who brings to her giftedness a work ethic that demands that she give her all in everything she takes up. Shortly after she began attending Duneland Friends Meeting, Marlou concentrated her efforts into developing our First Day School. This program would later become a model for many Illinois Yearly Meeting First Day Schools, and later, several throughout Friends General Conference. Marlou worked with the children, trained us as First Day School teachers, and continued to guide our children's religious education program for many years. Marlou's interest in education has been lifelong. She received a Bachelor of Science degree in elementary education at Indiana University, Bloomington, followed by a Master of Science degree from Purdue North Central. Additionally, she participated in Teacher Training Laboratory Schools for Religious Educators. Most recently, she completed the 1998—2000 session of School of the Spirit. Marlou has faithfully served our monthly meeting in other capacities as well. She has been our clerk, serves on the Ministry and Counsel Committee, and is currently our meeting treasurer. Marlou has often represented our monthly meeting when Duneland Friends participate in local meetings or community events. -

GENOME by Matt Ridley

The author is grateful to the following publishers for permission to reprint brief extracts: Harvard University Press for four extracts from Nancy Wexler's article in The Code of Codes, edited by D. Kevles and R. Hood (pp. 62-9); Aurum Press for an extract from The Gene Hunters by William Cookson (p. 78); Macmillan Press for extracts from Philosophical Essays by A. J. Ayer (p. 338) and What Remains to Be Discovered by J. Maddox (p. 194); W. H. Freeman for extracts from The Narrow Roads of Gene Land by W. D. Hamilton (p. 131); Oxford University Press for extracts from The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins (p. 122) and Fatal Protein by Rosalind Ridley and Harry Baker (p. 285); Weidenfeld and Nicolson for an extract from One Renegade Cell by Robert Weinberg (p. 237). The author has made every effort to obtain permission for all other extracts from published work reprinted in this book. This book was originally published in Great Britain in 1999 by Fourth Estate Limited. GENOME. Copyright © 1999 by Matt Ridley. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information please write: Special Markets Department, HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. -

Bulletin1611956smit.Pdf

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY BULLETIN 161 SEMINOLE MUSIC By Frances Densmore BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY BULLETIN 161 PLATE 1 Panther (Josie Billie). K UAA SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY BULLETIN 161 SEMINOLE MUSIC By FRANCES DENSMORE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1956 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1 (paper cover) KC -» 9 1956 Iff LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington, D. C, March 30, 1955. Sir: I have the honor to transmit herewith a manuscript entitled "Seminole Music," by Frances Densmore, and to recommend tliat it be published as a bulletin of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Very respectfully yours, M. W. Stirling, Director. Dr. Leonard Carmichael, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution. FOREWORD The Seminole of Florida are a Miiskhogean tribe orip^inally made up of immigrants who moved down into Florida from the Lower Creek towns on the Chattahoochee River. Their tribal name is de- rived from a Creek word meaning "separatist" or ''runaway," sug- gesting that they lack the permanent background of the tribes whose music had previously been studied.^ The writer's first trip to the Seminole in Florida was in January 1931, and the Indians observed were from the Big Cypress Swamp group. The second visit, begun in November 1931, continued until March of the following year, the study including both the Cypress Swamp and Cow Creek groups of the tribe. Two exhibition villages near Miami afforded an opportunity to see the native manner of life. These were Musa Isle and Coppinger's Tropical Gardens. -

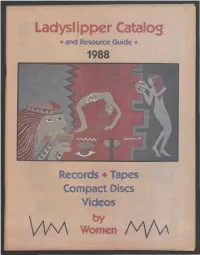

Ladyslipper Catalog • and Resource Guide • 1988

Ladyslipper Catalog • and Resource Guide • 1988 Records • Tapes Compact Discs Videos V\M Women Mf\A About Ladyslipper Ladyslipper is a North Carolina non-profit, tax- 1982 brought the first release on the Ladys exempt organization which has been involved lipper label Marie Rhines/Tartans & Sagebrush, in many facets of women's music since 1976. originally released on the Biscuit City label. In Our basic purpose has consistently been to 1984 we produced our first album, Kay Gard heighten public awareness of the achievements ner/A Rainbow Path. In 1985 we released the of women artists and musicians and to expand first new wave/techno-pop women's music al the scope and availability of musical and liter bum, Sue Fink/Big Promise; put the new age ary recordings by women. album Beth York/Transformations onto vinyl; and released another new age instrumental al One of the unique aspects of our work has bum, Debbie Fier/Firelight. Our purpose as a been the annual publication of the world's most label is to further new musical and artistic direc comprehensive Catalog and Resource Guide of tions for women artists. Records and Tapes by Women—the one you now hold in your hands. This grows yearly as Our name comes from an exquisite flower the number of recordings by women continues which is one of the few wild orchids native to to develop in geometric proportions. This anno North America and is currently an endangered tated catalog has given thousands of people in species. formation about and access to recordings by an expansive variety of female musicians, writers, Donations are tax-deductible, and we do need comics, and composers. -

Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Poetry Review Publications Spring 4-1-2006 Columbia Poetry Review Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Poetry Review" (2006). Columbia Poetry Review. 19. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr/19 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Poetry Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA PO E T RY REVIEW Spring 2006 COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO Columbia Poetry Review is published in the spring of each year by the English Department of Columbia College Chicago, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 60605. SUBMISSIONS Our reading period extends from August 1 to November 30. Please send up to 5 pages of poetry during our reading period to the above address. We do not accept e-mail submissions. We respond by mid-March. Any submissions without a SASE will not be returned. PURCHASE INFORMATION Single copies are available for $8.00, and for $11.00 outside the U.S. Please send personal checks or money orders made out to Columbia Poetry Review to the above address. WEBSITE INFORMATION To see a catalog of back issues (with sample works) visit Columbia Poetry Review’s website at http://www.colum.edu/undergraduate/english/poetry/ pub/cpr/. -

![[Soul Songs: Origins and Agency in African-American Spirituals]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1039/soul-songs-origins-and-agency-in-african-american-spirituals-10691039.webp)

[Soul Songs: Origins and Agency in African-American Spirituals]

[SOUL SONGS: ORIGINS AND AGENCY IN AFRICAN-AMERICAN SPIRITUALS] Courtesy of the National Endowment for the Humanities Jeneva Wright SERSAS 2013 1 The voice of the American slave is shrouded in mystery. Often illiterate and prohibited from public communication, most slaves could not share their histories and experiences. Yet one primary source points to many others, which not only served as evidence to the slave experience, but also depicted the desperate struggle to maintain one’s identity and humanity in a system that denied both. To Frederick Douglass, the spiritual: was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains…If any one wishes to be impressed with a sense of the soul-killing power of slavery, let him go to Col. Lloyd’s plantation, and, on allowance day, place himself in the deep, pine woods, and there let him, in silence thoughtfully analyze the sounds that shall pass through the chambers of his soul, and if he is not thus impressed, it will only be because “there is no flesh in his obdurate heart.”1 The culture of any ethnic group proclaims itself in varied expressions; art, literature, language, and dress all fall under the loose heading of culture. In the case of African-Americans, however, one of the most prevalent presentations of a unique culture and experience has been the creation and development of specific musical forms. These unique sounds are not only definitive of the culture that created them, but also speak loudly of the traditions of past tribal societies, and the milieu of slavery in the American South. -

Oral History Interview with Joyce J. Scott, 2009 July 22

Oral history interview with Joyce J. Scott, 2009 July 22 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Joyce Scott on July 22, 2009. The interview took place at Scott's home and studio in Baltimore, MD, and was conducted by Robert Silberman for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project For Craft and Decorative Arts in America. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ROBERT SILBERMAN: This is Robert Silberman interviewing Joyce Scott at the artist's home and studio in Baltimore, Maryland, on July 22, 2009, for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, card number one. Hello again, Joyce. JOYCE SCOTT: Hi. ROBERT SILBERMAN: Perhaps you could begin by talking about your childhood and your family. When were you born, to begin with the— JOYCE SCOTT: My name is Joyce Jane Scott. I was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1948 from Elizabeth Caldwell Talford Scott, who's from Chester, South Carolina, and Charlie Scott Jr., from Durham, North Carolina. My parents left the South—he picked tobacco, she picked cotton—on that immigration north to get better jobs. -

Emergent Identity of College Students in the Digital Age

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 #Becoming: Emergent Identity of College Students in the Digital Age Examined Through Complexivist Epistemologies Paul William Eaton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Eaton, Paul William, "#Becoming: Emergent Identity of College Students in the Digital Age Examined Through Complexivist Epistemologies" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3604. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3604 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. #BECOMING: EMERGENT IDENTITY OF COLLEGE STUDENTS IN THE DIGITAL AGE EXAMINED THROUGH COMPLEXIVIST EPISTEMOLOGIES A Dissertation SuBmitteD to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University anD Agricultural anD Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Education by Paul William Eaton B.A., University of Minnesota Twin Cities, 2002 M.ED, University of MarylanD College Park, 2005 May 2015 For my mother – who always gave me the space anD love to pursue my Dreams. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I will inaDvertently anD unintentionally miss the names of many people who have Been so critical in my reaching this personal anD acaDemic milestone. Completing a Doctorate is not a solo enDeavor. I hope all who have assisted, supported, challengeD, anD mentoreD me will accept my sincere gratituDe. -

Coley, WB, Ed. Ideas for English 101: Teaching Writing in National Co

0 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 111 023 CS 202 242 AUTHOR Ohmann, Richard, Ed.; Coley, W. B., Ed. TITLE Ideas for English 101: Teaching Writing in College. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English,Urbana, Ill. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801 (Stock No. 22450, $3.95 nonmember, $3.75 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$12.05 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS College Freshmen; *Composition (Literary); Composition Skills (Literary); *Educational Theories; *English Instruction; Higher Education; Instructional Materials; *Teaching Methods; Writing Skills ABSTRACT The articles in this book are concerned withteaching composition in freshman Englishcourses. They were first published in "College English" during the years from 1966 to1975. These selections represent both the theoretical discussionsand the technical plans which were put forth ina period when freshman English was being dropped asa required course in many colleges. The contents are divided into the following two sections: "WhatShould Freshman English Be? Methods and Controversies"and "Tactics." Among the essays included are "Toward Competence and Creativityin the Open Class" by Lou Kelly, "The Teaching of Writingas Writing" by W. E. Coles, Jr., "Hydrants Into Elephants: The Theoryand Practice of College Composition" by George Stade, "BehavioralObjectives for English" by Robert Zoellner, "'Topics' and Levels inthe Composing Process" by W. Ross Winterowd, "Using Painting,Photography and Film to Teach Narration" by Joseph Comprone, "TeachingFreshman Comp to New York Cops" by David Siff, "Cassettes in the Classroom"by Enno Klammer, and "What Students Can Do to Take the BurdenOff You" by Francine Hardaway.(JM) *********************************************************************** * Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * *materials not available from othersources. -

BALOO's BUGLE Volume 17, Number 8D "Make No Small Plans

BALOO'S BUGLE Volume 17, Number 8D "Make no small plans. They have no magic to stir men's blood and probably will not themselves be realized." D. Burnham --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- March 2011 Cub Scout Roundtable April 2011Activities FAITH Tiger Cub, Wolf, Bear, and Webelos Meetings 15 and 16 CORE VALUES TABLE OF CONTENTS Cub Scout Roundtable Leaders’ Guide In many of the sections you will find subdivisions for the The core value highlighted this month is: various topics covered in the den meetings Faith: Having inner strength or confidence based on CORE VALUES................................................................... 1 our trust in a higher power. Cub Scouts will learn that it COMMISSIONER’S CORNER........................................... 1 is important to look for the good in all situations. With THOUGHTFUL ITEMS FOR SCOUTERS ........................ 2 their family guiding them, Cub Scouts will grow TRAINING TOPICS ............................................................ 2 stronger in their faith ROUNDTABLES................................................................. 2 PACK ADMIN HELPS - ..................................................... 2 COMMISSIONER’S CORNER LEADER RECOGNITION, INSTALLATION & MORE... 2 Pow Wow Books needed (REALLY NEEDED) DEN MEETING TOPICS .................................................... 2 I need ideas for Baloo for the Core Values. This month is SPECIAL OPPORTUNITIES ............................................. -

Jamaican Children's Literature

Jamaican Children’s Literature: A Critical Multicultural Analysis of Text and Illustration in Jamaican Picturebooks for Children Published Between 1997 – 2012 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Wendy Scott Richards IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Lee Galda, Advisor July, 2013 Wendy Scott Richards, July, 2013 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Lee Galda for showing me this was possible. It is a high privilege to have been one of her academic advisees. Thanks to her instruction and patient guidance, I am a better person and scholar of children’s literature. I press forward with all I have learned about children’s literature, bringing her voice and her great influence to my own reading and into my classroom, passing it forward to teacher candidates and to young readers of children’s literature in the US and in Jamaica. I thank Dr. Lori Helman and Dr. Nicola Alexander for their instruction and guidance along the way. I gained significant knowledge of English Learners and of educational policy from their classes and I benefitted greatly from their influence and suggestions as part of my dissertation committee. I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Sarah Smedman, who advised me for my master’s degree in reading and my thesis in children’s literature at Minnesota State University, Moorhead, and now for my doctoral dissertation in literacy at the University of Minnesota. For sharing her time, her expertise in children’s literature and her loving guidance as my research took shape, I am forever grateful.