Oral History Interview with Joyce J. Scott, 2009 July 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altruism, Activism, and the Moral Imperative in Craft

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Altruism, Activism, and the Moral Imperative in Craft Gabriel Craig Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1713 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Gabriel Craig 2009 All Rights Reserved Altruism, Activism, and the Moral Imperative in Craft A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University by Gabriel Craig Bachelor of Fine Arts (emphasis in Metals/ Jewelry), Western Michigan University, 2006 Director: Susie Ganch Assistant Professor, Department of Craft/ Material Studies Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2009 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge several people who have contributed to my success and development as an artist, writer, and as a person of good character in general. First, I would like to thank my father, without whose support the journey would have been much more difficult, Amy Weiks whose unwavering love and support has provided the foundation that allows me to take on so many projects, Susie Ganch, whose mentorship, honesty, and trust have helped me to grow like a weed over the past two years, Natalya Pinchuk whose high standards have helped me to challenge myself more than I thought possible, Sonya Clark who baptized me into the waters of craft and taught me to swim, and Dr. -

Sheila Hicks

VOLUME 28. NUMBER 2. FALL, 2016 Sheila Hicks, Emerging with Grace, 2016, linen, cotton, silk, shell, 7 7/8” x 11”, Museum purchase with funds from the Joslyn Art Museum Association Gala 2016, 2016.12. Art © Sheila Hicks. Photo: Cristobal Zanartu. Fall 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Letter from the Editor Vita Plume Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) At TSA in Savannah we welcomed new board members and said good-bye to those President who have provided dedicated service for four or more years to our organization. Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] ALL Our talented executive director, Tali Weinberg has served us well, developing Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) F 2016 procedures that will serve us into the future and implementing board directed Editorial Assistance: Vita Plume (TSA President) Lisa Kriner Vice President/President Elect NEWSLETTER CONTENTS changes during her tenure. Tali is now stepping out to pursue her artwork with a [email protected] full time residency in Tulsa, Oklahoma for a year. I wish her well even as I will miss 3 Letter from the Editor working with her. Our Mission Roxane Shaughnessy Past President 4 Letter from the President [email protected] Our organization has embarked on developing a strategic plan in 2016 and is in the The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for 6 Letter from the Executive Director process of gathering input from a broad range of constituents, both members and the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Owyn Ruck non-members. -

Costura: De La Reivindicación Política a La Recreación Poética

COSTURA: DE LA REIVINDICACIÓN POLÍTICA A LA RECREACIÓN POÉTICA. EL PROCEDIMIENTO DE LA COSTURA COMO RECURSO CREATIVO EN LA OBRA DE ARTE. TESIS DOCTORAL MARÍA MAGÁN LAMPÓN Directora: Dª Consuelo Matesanz Pérez Universidad de Vigo, 2015 COSTURA: DE LA REIVINDICACIÓN POLÍTICA A LA RECREACIÓN POÉTICA. EL PROCEDIMIENTO DE LA COSTURA COMO RECURSO CREATIVO EN LA OBRA DE ARTE. TESIS DOCTORAL MARÍA MAGÁN LAMPÓN Directora: Dª Consuelo Matesanz Pérez Universidad de Vigo, 2015 COSTURA: DE LA REIVINDICACIÓN POLÍTICA A LA RECREACIÓN POÉTICA. EL PROCEDIMIENTO DE LA COSTURA COMO RECURSO CREATIVO EN LA OBRA DE ARTE. TESIS DOCTORAL MARÍA MAGÁN LAMPÓN Directora: Dª Consuelo Matesanz Pérez Departamento de Pintura, Facultad de Bellas Artes Universidad de Vigo Pontevedra, Mayo, 2015 María Magán Lampón Imágenes: sus respectivos autores Licencias: El contenido de este trabajo está sujeto a una licencia “Creative Commons 3.0”. Se puede reproducir, distribuir, comunicar y transformar los contenidos incluidos en este documento y en el CD-ROM adjunto, si se reconoce su autoría y se realiza sin ánimo de lucro. El copyright de las imágenes de las obras corresponde a sus respectivos autores. Impresión y Encuadernación Códice Pontevedra, 2015 Agradecimientos Es complicado entender la importancia de los agradecimientos de una tesis doctoral hasta que no se ha terminado; es entonces cuando miras atrás y te das cuenta de la ayuda y apoyo que has recibido. Intentaré resumir en unas líneas la gratitud que siento a todas las personas que han estado presentes durante esta etapa. Mi más cálido agradecimiento a Chelo Matesanz, directora de la tesis y ahora amiga, con quien he recorrido un largo camino desde el momento en que planteamos el tema de la investigación. -

Focus Working Potters Diana Fayt

focus MONTHLY working potters working Diana Fayt focus working potters JUNE/JULY/AUGUST 2009 $7.50 (Can$9) www.ceramicsmonthly.org Ceramics Monthly June/July/August 2009 1 The MONTHLY Publisher Charles Spahr Editorial [email protected] Robin Hopper telephone: (614) 895-4213 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall assistant editor Holly Goring Trilogy assistant editor Jessica Knapp editorial assistant Erin Pfeifer The Robin Hopper Trilogy covers every important aspect of creating technical editor Dave Finkelnburg online editor Jennifer Poellot Harnetty ceramic art. The Ceramic Spectrum guides you through a non-mathe- Advertising/Classifieds matical easy-to-understand journey for getting the colors and glazes you [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5834 want. In Functional Pottery, you’ll be able to develop your own designs fax: (614) 891-8960 classifi[email protected] and methods for the pots you use. And in Making Marks you’ll discover telephone: (614) 794-5843 advertising manager Mona Thiel the many possibilities of enriching your surfaces. advertising services Jan Moloney Marketing telephone: (614) 794-5809 marketing manager Steve Hecker Subscriptions/Circulation COLOR customer service: (800) 342-3594 [email protected] Design/Production production editor Cynthia Griffith The Ceramic Spectrum design Paula John Editorial and advertising offices A Simplified Approach to Glaze 600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, Ohio 43082 & Color Development Editorial Advisory Board Linda Arbuckle; Professor, -

December 2019 Dear Friend, This Has Truly Been a Groundbreaking Year at Haystack. We Celebrated the Opening Of

HAYSTACK MOUNTAIN December 2019 SCHOOL OF CRAFTS P.O. BOX 518 DEER ISLE, ME 04627 Dear Friend, 207.348.2306 FAX: 207.348.2307 This has truly been a groundbreaking year at Haystack. [email protected] haystack-mtn.org We celebrated the opening of “In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of FOUNDER Crafts 1950-1969,” the first exhibition of its kind to provide an overview of the Mary B. Bishop (1885–1972) founding years and impact of the school. Organized by the Portland Museum of FOUNDING DIRECTOR Art, the exhibition had record attendance and garnered critical praise from The Francis S. Merritt (1913–2000) Boston Globe, The Portland Press Herald, The Washington Post, and others. For the third consecutive year we exceeded historic fundraising records and BOARD OF TRUSTEES recently announced the largest single gift in the history of the school, to Jack Lenor Larsen Honorary Chair establish a permanently restricted endowment for campus preservation. Through new and expanded partnerships that provided direct support to those Susan Haas Bralove President who have been historically underrepresented in the field, we continued our Ayumi Horie commitment to become a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive organization. Vice President We also launched a new pilot program with OUT Maine, designed for LGBTQ Laura Galaida teens with the goal of empowering and inspiring young people to see Treasurer themselves in their fullest capacity while modeling an open and out life in the M. Rachael Arauz arts. None of this would have been possible without your support. Katherine Cheney Chappell Sonya Clark Annet Couwenberg One of the ways you can make an impact is through a gift to the Haystack annual Deborah Cummins fund. -

9 Sonya Clark Catalog.Indd

SONYA CLARK SONYA CLARK Snyderman Gallery Philadelphia, Pennsylvania October 1, 2011 – November 19, 2011 Southwest School of Art San Antonio, Texas December 8, 2011 – February 12, 2012 Front Cover. Adrienne’s Tale © 2011. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission from the Southwest School of Art. ISBN number 0-9742914-4-7 SONYA CLARK Heritage Pearls Foreword It is an honor to present Sonya Clark’s solo exhibition at the Southwest School of Art. Her works, charged with meaning and message, are made even more powerful by the evocative materials and physical processes she employs. Trained in the fiber arts, Clark today weaves together not threads but ideas and symbols in order to produce elegant yet demanding works of art. The visceral but quotidian properties of her works, as well as their exquisite execution, force our attention, compelling the viewer to grapple with their sweeping implications. To explore the poignancy and potency of lineage and the biases of history through works of art requires unique cognitive and perceptive skills. We are grateful to Sonya Clark for sharing those skills with us and also to Rick Snyderman of Snyderman Gallery in Philadelphia, our partner in this exhibition, and to essayists, Ashley Kistler of Richmond, Virginia and Namita Gupta Wiggers of Portland, Oregon. PAULA OWEN President, Southwest School of Art 3 Artist in her studio Acknowledgements Artist Statement Recently I gained a new ancestor. I investigate simple objects as cultural He was a man who understood if you possess passion, work interfaces. Through them I navigate accord and discord. -

“The Inhabitants of the Deep:” Water and the Material Imagination of Blackness

“The Inhabitants of the Deep:” Water and the Material Imagination of Blackness by Jonathan Howard Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: __________________________ Nathaniel Mackey, Chair __________________________ Frederick Moten __________________________ Priscilla Wald __________________________ J. Kameron Carter Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 ABSTRACT “The Inhabitants of the Deep:” Water and the Material Imagination of Blackness by Jonathan Howard Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: __________________________ Nathaniel Mackey, Chair __________________________ Frederick Moten __________________________ Priscilla Wald __________________________ J. Kameron Carter An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Jonathan-David Mackinley Howard 2017 Abstract And Moses said, “I will turn aside to see this great sight, why the bush is not burned.” If the biblical Exodus begins with Moses turning to see the bush burning, yet not consumed, my dissertation turns aside to see that “sign and wonder” which arguably founds the kindred exodus of the African Diaspora. That great, if impossible, sight which Olaudah Equiano beheld from the deck of a slave ship: the -

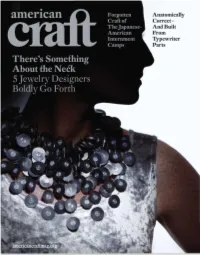

Anatomically Correct- Andbuilt from Typewriter Parts

Anatomically Correct AndBuilt From Typewriter Parts • ' THE AMERICAN CRAFT COUNCIL SHOW 0' . jiwE~~~ ~ c~OTHI~G • FURNnu~i • H~~E· oECoR · · · WWW .CRAFTCOUNCIL.ORG • More at ebook-free-download.net or magazinesdownload.com CONTENTS • amertcan Departments o6 024 From the Editor Review A miracle in the making. Christy DeSmith taps into The New Materiality, curator o8 Fo Wilson's provocative Zoom exploration of digital Jeremy Mayer's typewriter technology in contemporary Vol. 70, No.6 sculptures andAlbertus craft at the Fuller Craft December 2oxojjanuary 2011 Swanepoel's hats, plus a visit to Museum. Denver's Show of Hands gallery, Published by the new books on Jack Len or 026 American Craft Council Larsen's LongHouse and Material Matters www.craftcouncil.org Wharton Esherick's life and Gregg Graff andJacqueline work, innovation at Oregon Pouyat devised a wax formula College of Art and Craft, and to preserve the seeds, pods dispatches from the field: news, and reeds in their minimalist voices and shows to see. vignettes. Monica Moses re ports on these natural archivists. americancraftmag.org 030 More photos, reviews, listings, Personal Paths interviews and everything craft In her mixed-media sculptures, related and beyond. Susan Aaron-Taylor re-creates the landscape of her dreams, informed by CarlJung's spiritually charged concepts. Roger Green probes the meaning of her unusual art. 062 Considering ... With the mundane soccer ball as a starting point, Glenn Adamson ponders the meaning, potential and limitations of handmade objects in our globalized age. o68 Above: Wide World ofCraft Jeremy Mayer Hawaii's natural beauty has Deer III (side view), zoro, attracted and inspired a hub of typewriter parts, 36xr6x36in. -

Introduction of Marlou Carlson, by Roxy Jacobs

Plummer Lecture Given to Illinois Yearly Meeting, Seventh Month 2001 Marlou Carlson Introduction of Marlou Carlson, by Roxy Jacobs Most Friends know that Marlou and I share a friendship that we have carefully tended for approximately 20 years. Though arriving by separate paths, we both came to Duneland Friends Meeting at approximately the same time. It was in this context that I came to know Marlou Carlson as a woman who was favored by God with many gifts, and who brings to her giftedness a work ethic that demands that she give her all in everything she takes up. Shortly after she began attending Duneland Friends Meeting, Marlou concentrated her efforts into developing our First Day School. This program would later become a model for many Illinois Yearly Meeting First Day Schools, and later, several throughout Friends General Conference. Marlou worked with the children, trained us as First Day School teachers, and continued to guide our children's religious education program for many years. Marlou's interest in education has been lifelong. She received a Bachelor of Science degree in elementary education at Indiana University, Bloomington, followed by a Master of Science degree from Purdue North Central. Additionally, she participated in Teacher Training Laboratory Schools for Religious Educators. Most recently, she completed the 1998—2000 session of School of the Spirit. Marlou has faithfully served our monthly meeting in other capacities as well. She has been our clerk, serves on the Ministry and Counsel Committee, and is currently our meeting treasurer. Marlou has often represented our monthly meeting when Duneland Friends participate in local meetings or community events. -

From the Director

2019 Haystack Campus, Montville, Maine, August 1955. Photo by Walter Holt FROM THE DIRECTOR This summer, the Portland Museum of Art will structure of learning is horizontal, with students and present the exhibition In the Vanguard: Haystack faculty working side by side to exchange ideas and Mountain School of Crafts, 1950-69. Organized by make new discoveries. co-curators Rachael Arauz and Diana Greenwold, this While the world has changed significantly, the core exhibition represents four years of research and is the of our work and the ideals we adhere to have stayed first of its kind to provide an overview of the founding very much the same. Our greatest hope is that the years of the school. experimentation and risk-taking that defined the To have our story told in this way has been an founding of the school continue to underscore incredible privilege and we could not be more excited the work we do today. Looking ahead to our 70th about the project and the research that has led up to anniversary, this exhibition feels like a defining it. The show will present archival materials such as moment that allows us to step back and think about original correspondence, photographs, brochures, the quiet and profound ways in which Haystack posters, magazine articles, and ephemera, alongside has helped shape American art and culture. The objects created during the same time period by exhibition is also a beautiful reminder that people prominent makers who taught and studied at coming to the school today are helping to create the Haystack. Much of this material has never been next chapter in a story continually unfolding in rich published and will be included in a catalogue and unexpected ways. -

Toward Textiles

toward textiles © 2015 John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI toward textiles Contents 3 Material Fix Alison Ferris 9 Ebony G. Patterson: Dead Treez Karen Patterson 11 Joan Livingstone: Oddment[s] Karen Patterson 13 Ann Hamilton: draw Alison Ferris 14 Sandra Sheehy and Anna Zemánková: Botanical Karen Patterson 16 Carole Frances Lung: Factory To Factory Karen Patterson 17 Checklist of Works Cover: Anne Wilson, Dispersions (no. 24, detail), 2013; linen, cotton, thread, and hair; 25 ¼ x 25 ¼ in. Courtesy of the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, IL. Photo: Adam Liam Rose. MATERIAL FIX Alison Ferris “I worry that the information age is making us very good at symbolization at the expense of bringing us into contact with that which we do not know and for which we have no categories.”1 —Laura U. Marks In recent years, fiber art has eluded characterization as it has infiltrated traditional art practices and expanded into installation and performance. As fiber-based art has grown more mainstream, however, its material-based, multidisciplinary practice risks being compromised, overlooked, or assimilated by the contemporary art world. Material Fix is a contemplation of fiber’s unique material specificity and the ways a range of artists join process with current theoretical and aesthetic concerns. The exhibition examines the manner in which the artists in Material Fix insist on the materiality of their work, Jen Bervin, The Dickinson Fascicles: The Composite Marks of Fascicle questioning the detached sense of vision associated 28, 2006; cotton and silk on cotton and muslin; 72 x 96 in. Courtesy of with this digital age where appearances are often separate the artist. -

For Immediate Release Objects

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OBJECTS: REDUX—50 Years of Craft Evolution January 31–March 27, 2020 VIP PREVIEW: RSVP ONLY Thursday, January 30, 5 -7pm OPENING NIGHT Friday, January 31, 5 -7pm CURATOR’S TALK WITH KATHRYN HALL Saturday, February 1, 2pm SCREENING & ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION Saturday, March 14, 2pm © J. Fred Woell FROM 1969 TO TODAY: 50 YEARS OF CRAFT EVOLUTION (January 2020) form & concept is thrilled to present OBJECTS: REDUX—50 Years of Craft Evolution, featuring over 70 pieces by seminal historical and contemporary craft artists, including J. Fred Woell, Sonya Clark, Ken Cory, Raven Halfmoon, Nicki Green, Jennifer Ling Datchuk and Kat Cole, among others. Ranging from textile, jewelry, metal, and enamel to wood, ceramics and glass, the exhibition positions work from the original 1969 OBJECTS: USA show alongside innovative craft objects and wearables by contemporary makers. In 1969, the Smithsonian American Art Museum debuted OBJECTS: USA, a sprawling exhibition featuring 308 craft artists and over 500 objects. The show would travel the United States and Europe, vaulting craft into the contemporary art milieu and forever changing the way we view material culture. Fifty years later, this tribute exhibition incorporates work by artists in the original display alongside historic and contemporary makers who expand upon and complicate the conversation. If OBJECTS: USA first established the field of craft as a vital component of the fine art world conversation, OBJECTS: REDUX demonstrates not only modern craft artists’ keen sense and appreciation of their predecesors, but also the field’s ongoing spirit of boundary-defying inventiveness and material resourcefulness. Curator William Dunn writes, “It’s wonderful to be a part of this show’s continued legacy.