Some Insights from a Comparison of the German and Us-American Synthetic Rubber Programs Before, During and After World War 11.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hahn on Finlay, 'Growing American Rubber: Strategic Plants and the Politics of National Security'

H-Environment Hahn on Finlay, 'Growing American Rubber: Strategic Plants and the Politics of National Security' Review published on Wednesday, January 18, 2012 Mark R. Finlay. Growing American Rubber: Strategic Plants and the Politics of National Security. Studies in Modern Science, Technology, and the Environment Series. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009. xiii + 317 pp. $49.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8135-4483-0. Reviewed by Barbara Hahn (Texas Tech University) Published on H-Environment (January, 2012) Commissioned by Dolly Jørgensen Rubber and Empire “We could recover from the blowing up of New York City and all the big cities of the eastern seaboard,” declared Harvey S. Firestone in 1926, “more quickly ... than we could recover from the loss of our rubber” (p. 63). Firestone, of course, relied on rubber for his tire empire; his explosive example was no less true for that. Rubber was a crucial input for most twentieth-century technologies: it contributed insulation for telegraph wires as well as tires for automobiles, bicycles, trucks, and airplanes. It also made rubber gloves and medical tubing, condoms, and tennis shoes. From hospitals to auto repair shops, rubber went into every industry--both Henry Ford and Thomas Edison counted it an input. In 1942, the United States consumed 60 percent of the world’s rubber but produced almost none; 97 percent was produced in the Pacific, in regions that had fallen to the Japanese after Pearl Harbor. The U.S. government rationed gasoline during World War II--primarily to protect the supplies of rubber that would otherwise be used in tires, by motorists. -

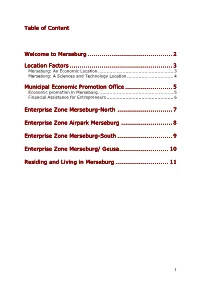

Table of Content

Table of Content Welcome to Merseburg ........................................................................... ................................ ......................2222 Location Factors ................................................................................... ..................... 333 Merseburg: An Economic Location .................................................... 3 Merseburg: A Sciences and Technology Location ................................ 4 Municipal Economic Promotion Office ........................ ........................ 555 Economic promotion in Merseburg.................................................... 5 Financial Assistance for Entrepreneurs .............................................. 6 EnEnEnterpriseEn terprise Zone MerseburgMerseburg----NorthNorth ............................ 777 Enterprise Zone Airpark Merseburg .......................... 888 Enterprise Zone MerseburgMerseburg----SouthSouth ............................ 999 Enterprise Zone Merseburg/ GeusaGeusa.................................................. 101010 Residing and Living in Merseburg ........................... ........................... 111111 1 Welcome to Merseburg The region around Merseburg is an Fraunhofer pilot plant center (PAZ) for industrial location which has polymer synthesis and polymer developed for more than 100 years. processing at Schkopau ValuePark. The chemicals industry set up and Last but not least, due to soft location established on a large-scale its factors e.g. wide-ranging leisure and businesses in neighboring -

Im Fokus: Industrielle Kerne in Ostdeutschland Und Wie Es Dort Heute Aussieht – Das Beispiel Des Chemiestandorts Schkopau

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Heimpold, Gerhard Article Im Fokus: Industrielle Kerne in Ostdeutschland und wie es dort heute aussieht – Das Beispiel des Chemiestandorts Schkopau Wirtschaft im Wandel Provided in Cooperation with: Halle Institute for Economic Research (IWH) – Member of the Leibniz Association Suggested Citation: Heimpold, Gerhard (2016) : Im Fokus: Industrielle Kerne in Ostdeutschland und wie es dort heute aussieht – Das Beispiel des Chemiestandorts Schkopau, Wirtschaft im Wandel, ISSN 2194-2129, Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Halle (IWH), Halle (Saale), Vol. 22, Iss. 4, pp. 73-76 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/148287 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Wirtschaft im Wandel — Jg. -

In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of A

IN SEARCH OF THE AMAZON AMERICAN ENCOUNTERS/GLOBAL INTERACTIONS A series edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Emily S. Rosenberg This series aims to stimulate critical perspectives and fresh interpretive frameworks for scholarship on the history of the imposing global pres- ence of the United States. Its primary concerns include the deployment and contestation of power, the construction and deconstruction of cul- tural and political borders, the fluid meanings of intercultural encoun- ters, and the complex interplay between the global and the local. American Encounters seeks to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between histo- rians of U.S. international relations and area studies specialists. The series encourages scholarship based on multiarchival historical research. At the same time, it supports a recognition of the represen- tational character of all stories about the past and promotes critical in- quiry into issues of subjectivity and narrative. In the process, American Encounters strives to understand the context in which meanings related to nations, cultures, and political economy are continually produced, chal- lenged, and reshaped. IN SEARCH OF THE AMAzon BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NATURE OF A REGION SETH GARFIELD Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in - Publication Data Garfield, Seth. In search of the Amazon : Brazil, the United States, and the nature of a region / Seth Garfield. pages cm—(American encounters/global interactions) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Germany's Chemical and Related Process Industry 2011

Germany’s Chemical and Related Process Industry 2011 A Profile of Selected Investment Sites Industry Brochure DENMARK Germany’s Chemical and Related Process Industry DENMARK Selected Investment Sites Site Name Location Page 1 Bayer Industrial Park Brunsbüttel Brunsbüttel 18 2 ChemCoast Park Brunsbüttel Brunsbüttel 20 3 CoastSite Wilhelmshaven Wilhelmshaven 22 POD LAN 4 Dow ValuePark® Stade Stade 24 5 IndustriePark Lingen Lingen 26 6 Industriepark Walsrode Walsrode-Bomlitz 28 T HE NETHERLANDS 7 Honeywell Specialty Chemicals Seelze Seelze 30 8 Baltic Industrial Park Schwerin Schwerin 32 9 Industrial Park Schwedt Schwedt 34 10 Chemical Site Schwarzheide Schwarzheide 36 11 Industrie- und Gewerbepark Altmark Arneburg 38 12 Agro-Chemie Park Piesteritz Wittenberg-Piesteritz 40 13 ChemiePark Bitterfeld Wolfen Bitterfeld Wolfen 42 14 Dow ValuePark® Schkopau 44 15 Chemical Site Leuna Leuna 46 16 Industriepark Schwarze Pumpe Spremberg 48 17 Marl Chemical Park Marl 50 18 Dorsten-Marl Industrial Park Dorsten/Marl 52 19 Chemical Park RÜTGERS Castrop-Rauxel 54 20 Gelsenkirchen Site Gelsenkirchen 56 BELM GIU 21 Deutsche Gasrußwerke Dortmund 58 22 Chemiepark Bayer Schering Pharma Bergkamen 60 23 CHEMPARK Krefeld-Uerdingen Krefeld-Uerdingen 62 24 Bayer Schering Pharma AG Wuppertal Elberfeld 64 LUXEM- National Borders BOURG CZECH REPUBLIC 25 Industriepark Oberbruch Heinsberg 66 Major Railways 26 CHEMPARK Dormagen Dormagen 68 Major Autobahns 27 CHEMPARK Leverkusen Leverkusen 70 28 Chemical Industrial Park Knapsack Knapsack-Hürth 72 SelectedNavigable Sites -

ELMER KEISER BOLTON June 23, 1886-Jidy 30, 1968

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES E LMER KEISER BOLTON 1886—1968 A Biographical Memoir by RO BE R T M. J O Y C E Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1983 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. ELMER KEISER BOLTON June 23, 1886-Jidy 30, 1968 BY ROBERT M. JOYCE LMER KEISER BOLTON was one of the outstanding leaders E of industrial research. He became an industrial re- search director at a time when research was only beginning to be a significant factor in the chemical industry. There were no models for this new role, and Bolton's concepts of direct- ing industrial research were in large measure those that he formulated himself, reflecting his vision and drive to achieve important commercial goals. The record of industrial products developed by Du Pont research organizations that he directed is impressive; it in- cludes synthetic dyes and intermediates, flotation chemicals, rubber chemicals, neoprene synthetic rubber, nylon synthetic fiber, and Teflon® polytetrafluoroethylene resin. His leader- ship in bringing these developments to fruition was always apparent to management and to those he directed, but be- cause of his characteristic self-effacement his name is not widely associated with these accomplishments. Throughout his career he supported and encouraged his technical person- nel. Most important, he had the knack of picking the right time and direction to take in moving a research lead into development. Many of his decisions proved crucial to the ultimate success of these ventures. -

Congress! on Al Record-House '6029

1928· . CONGRESS! ON AL RECORD-HOUSE '6029 MEMOB:A:.".DUM RELATL"G TO GEORGE WA.SIIIXGTOX ' :UE~IORIAL BUILDING ADJOURNMENT U~TIL SU~DAY It seems very strange that when we are planning to celebrate in 1932' Mr. CURTIS. I move that the Senate adjomn until Sunda.Y - the two hundredth anniversary of Washington's birth we do not con- next at 3 o'clock p. m., the hour fixed for· memorial addresses ider the importance of finishing the George Washington Memorial on the late Senator .To Es of New Mexico. · Building, for which Congress has given the land for the distinct purpose The motion was agreed to; and (at 4 o'clock and 45 minutes of carrying out George Washington's wish as expressed in his lastj p. m.) the Senate adjourned until Sunday, April 8, 1928, at 3 message to Congress, " Promote an institution for the diffusion of o'clock p. m. knowledge." · , Thjs building is. a peoples' building, a place where all national and 1 COI"FIRUATIOXS - international societies can meet. All State conventions pertaining to· ducational matters will be wel'Comed. What is more fitting than to E.recuti1:.e nomination confirmed by the Senate April 5 (legis hold this 1932 celebration in this auditorium, where can be seated from lative day ot April ~), 1928 seven to eleven thousand persons? Sevt>ral smallet· halls with a seating1 AMBASSADOR EX'IRAORDIN ARY AKD PLENIPOTENTIARY capacity from 500 to 2,500. A banquet ball seating 900. The people .Jo. eph C. Grew to be ambassador extraordinary and pleni should be roused to the importance of completing this building. -

Zupacken Für Die Region

Ausgabe 02 · Dezember 2012 HALLO Eine Zeitung der Dow Olefi nverbund GmbH für die Nachbargemeinden NACHBAR Editorial Liebe Nachbarn, Zupacken für die Region liebe Leser, die mitteldeutschen Dow-Standorte 180 Dow-Ingenieure aus der ganzen Welt tauschten einen Tag lang Computer und Reagenzglas gegen Pinsel und Schaufel. haben in diesem Jahr erneut ihre wirtschaftliche Leistungsstärke unter Beweis gestellt. Auch unsere Wenn sich der internationale Sicherheitsarbeit konnten wir Dow-Nachwuchs zu einem Work- weiter verbessern und arbeiten mit shop in Mitteldeutschland trifft, unseren Partnern seit fast 300 Tagen profi tieren davon auch die Nach- unfallfrei (Anm. d. Redaktion: Stand bargemeinden. Bereits das dritte 16.11.2012). Ein Ergebnis, auf das Jahr in Folge halfen im August wir sehr stolz sind. junge Ingenieure aus aller Welt in Dennoch ist angesichts der europä- sozialen Einrichtungen der Region. ischen Schuldenkrise, schwankender Ingrid Heroguel, Ingenieurin bei Rohstoffpreise und des nachlas- Dow im badischen Rheinmünster, senden Wirtschaftswachstums in ist geschafft, aber begeistert: „Es Europa und Asien die Stimmung ist fantastisch! Selbst nach den nicht ungetrübt. Um Wettbe- anstrengenden Seminaren, die wir werbsfähigkeit und Kosteneffi zienz seit einer Woche absolvieren, holt sicherzustellen, musste auch Dow hier trotzdem jeder noch einmal mit einem Sparprogramm auf die das Letzte aus sich heraus.“ Die weiterhin schwache Weltwirt- 26-Jährige ist seit einem Jahr bei schaftslage reagieren. Das Programm Dow und freut sich, dass der Kin- umfasst u. a. Veränderungen in der dergarten in Großdeuben nahe globalen Organisationsstruktur, die dem Dow-Werk Böhlen durch Stilllegung von 20 Produktionsanla- ihre Hilfe vorankommt. Ines gen und eine Reduzierung von 2.400 Walter, Geschäftsführerin des Arbeitsplätzen weltweit. -

Socio-Psychiatric Service in the Public Health Department

inform, Head of the Socio-Psychiatric Service support and Michael Kuppe liaise Medical specialist for psychiatry and psychotherapy Oberaltenburg 4b 06217 Merseburg Socio-psychiatric The Socio-Psychiatric Service offers support, coun- selling and guidance for people with Tel.: 03461 40-1707 Service in the Public Fax: 03461 40-1702 • mental impairments Email: [email protected] Health Department • addiction problems • psychological and intellectual impairments free | private | anonymous Psychiatry and addiction coordinator as well as relatives and interested individuals. Simone Küchler Experienced social workers will be at your disposal, Tel.: 03461 40-1711 and on request a doctor can also be consulted. Fax: 03461 40-1702 Email: [email protected] We recommend that you consult as by telephone in advance to make an appointment. Mailing adress In special cases house visits are possible. Please do not hesitate to contact us! Landkreis Saalekreis Gesundheitsamt Postfach 1454 06204 Merseburg www.saalekreis.de YOU ALWAYS HAVE TO BRING A TRANSLATOR WHO SPEAKS GERMAN! Photo credits: Title: © naka - stock.adobe.com Inside: © Prostock-studio - stock.adobe.com Public Health Department in the Oberaltenburg in Merseburg Back: © Landkreis Saalekreis We offer Contacs …for people with mental illnesses and handicaps and people with intellectual disabilities Merseburg Main Office Querfurt sub-office • Individual discussions and appointments with rela- tives Oberaltenburg 4b, 06217 Merseburg Kirchplan 1, 06268 Querfurt • Information about help for the affected and their relatives Fax no. of the site: Fax no. of the site: • Information about personal issues and information 03461 40-1702 034771 73797-33 regarding social law • Assistance for visits to public authorities and con- Tuesday 08:00 - 12:00 and 13:00 - 17:30 hours tacting other institutions Monday - Friday 08:00 – 12:00 hours Thursday 08:00 - 12:00 hours • Support in case of difficulties at the workplace, Tuesday 13:00 – 17:30 hours conflicts with relatives, friends, neighbours etc. -

Flächennutzungsplan Landsberg

FLÄCHENNUTZUNGSPLAN LANDSBERG Begründung gemäß § 5 Abs. 5 BauGB GENEHMIGUNGSFASSUNG November 2017 Auftraggeber: Stadt Landsberg Köthener Straße 2 06188 Landsberg Auftragnehmer: StadtLandGrün Stadt- und Landschaftsplanung Hildegard Ebert, Astrid Friedewald, Anke Strehl Am Kirchtor 10 06108 Halle Tel. (03 45) 239 772 13 Fax (03 45) 239 772 22 Autoren: Dipl.-Ing. Architekt für Stadtplanung Astrid Friedewald Stadtplanung Dipl.-Geogr. Christine Freckmann Stadtplanung Dipl.-Agraring. Anke Strehl Landschaftsplanung Yvette Trebel CAD-Bearbeitung Vorhaben: Ergänzung und Änderung des Flächennutzungsplans der Stadt Landsberg und Zusammenführung mit den einzelnen Ortschafts-FNP Ergänzung des FNP Landsberg um die Ortschaft Sietzsch durch Neuaufstellung des FNP Sietzsch und Ergänzung des FNP Landsberg um die Ortschaft Hohenthurm und Spickendorf und Fortschreibung der FNP-Verfahrensstände Zusammenführung und Einarbeitung von 1. Änderungen in den rechtswirksamen FNP der Ortschaften Braschwitz, Schwerz Zusammenführung und Einarbeitung von 2. Änderungen in den rechtswirksamen FNP der Ortschaften Landsberg, Niemberg, Oppin, Queis Zusammenführung und Einarbeitung von 4. Änderungen im rechtswirksamen FNP der Ortschaft Queis, Reußen Erstellung eines Umweltberichtes zu den Ergänzungen und Änderungen des FNP Vorhaben-Nr.: 13-119 Bearbeitungsstand: Genehmigungsfassung November 2017 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 0 Bedeutung und Aufgabe des Flächennutzungsplans (FNP) .............................. 10 1 Einführung ............................................................................................................. -

Tourenplan 2021 Entsorgungstermine Für Den Landkreis Saalekreis

Tourenplan 2021 Entsorgungstermine für den Landkreis Saalekreis Verbandsgemeinde: Weida-Land Einheitsgemeinden: Bad Dürrenberg, Bad Lauchstädt, Braunsbedra, Kabelsketal, Landsberg, Leuna, Merseburg, Mücheln, Petersberg, Querfurt, Salzatal, Schkopau, Teutschenthal, Wettin-Löbejün Inhaltsverzeichnis Allgemeine Hinweise/Informationen zur Abfallentsorgung ..... 2 Restabfallentsorgung/Weihnachtsbäume ............................ 7 Bioabfallentsorgung/Reinigung Biotonne .......................... 13 Papierentsorgung ......................................................... 18 Gelbe Tonne ................................................................ 25 Baum- und Strauchschnitt ............................................. 30 Schadstoffmobil ........................................................... 34 Formular Abfallentsorgung ............................................. 38 ! Bitte Änderungen beachten ! Sie finden uns auch im Internet unter www.saalekreis.de Allgemeine Hinweise / Informationen zur Abfallentsorgung Die zur Leerung und Entsorgung vorgesehenen Abfallbehälter und Abfälle sind am Abfuhrtag bis 6.00 Uhr am Straßenrand bzw. am festgelegten Bereitstellungsplatz abzustellen. Wenn durch Bautätigkeiten oder andere Behinderungen (z. B. Schnee und Eis) Ihre Straße zeitweise nicht befahrbar ist, bringen Sie Ihre Abfallbehälter und Abfälle an einen geeigneten Bereitstellungsort, an den die Entsorgungsfahrzeuge heranfahren können. Kennzeichnen Sie Ihre Behälter, damit diese nicht vertauscht werden – dazu kann auch ein entsprechender Aufkleber -

Facts and Figures: Dow in Central Germany

Daten und Fakten Dow in Mitteldeutschland Dow weltweit Dow in Deutschland Rostock Dow ist ein weltweit agierendes Chemieunternehmen mit Hauptsitz Das Engagement von Dow in Deutschland Stade in Midland/Michigan, USA. Das Unternehmen ist einer der weltweit begann 1960 mit der Gründung des ersten Ohrensen führenden Hersteller von Basis- und Spezialchemikalien sowie Hoch- Verkaufsbüros in Frankfurt am Main. Heute Bomlitz leistungswerkstoffen. 1897 von Herbert Henry Dow gegründet, macht ist Dow an 13 Standorten in ganz Deutsch- es sich das Unternehmen heute wie damals zur Aufgabe, das Leben land tätig und beschäftigt rund 3.600 Mit- Berlin der Menschen mithilfe von Wissenschaft und Technik nachhaltig zu arbeiter. Die größten Produktionsstandorte Ahlen Teutschenthal Bitterfeld verbessern. befinden sich in Mitteldeutschland und Sta- Schkopau Leuna de, Niedersachsen. Böhlen Wiesbaden • Umsatz 2018 > 50 Milliarden US-Dollar • Umsatz 2018 3,2 Milliarden US-Dollar • Mitarbeiter 37.000 • Mitarbeiter 3.600 • Hauptsitz Michigan (USA) • Standorte 13 Rheinmünster • Standorte > 113 Produktions- standorte in 31 Ländern 2 3 Dow in Mitteldeutschland Seit Mitte der 90er-Jahre ist Dow in Mitteldeutschland aktiv. Mit der Zum Produktportfolio gehören vor allem hochleistungsfähige Kunst- Übernahme des mitteldeutschen Olefinverbundes im Jahr 1995 wur- stoffe und Spezialchemikalien. Zudem betreibt Dow seit 1998 mit den veraltete, nicht wettbewerbsfähige Anlagen zu modernen Produk- dem ValuePark einen modernen und leistungsstarken Chemiepark tionsstätten entwickelt. Heute stehen die Standorte Böhlen, Schko- für kunststoffverarbeitende Unternehmen und chemienahe Dienstleis- pau, Leuna und Teutschenthal für innovative Technologien, hohe ter. Damit wird die Einbindung ansässiger Partner in die vielfältigen Produktivität und ausgezeichnete Ergebnisse in der Arbeitssicherheit Stoffströme, Liefer- und Leistungsketten gesichert. Bislang haben sich und beim Umweltschutz.