ES Book.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Literature Cited

Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This is a consolidated list of all works cited in volumes 19, 20, and 21, whether as selected references, in text, or in nomenclatural contexts. In citations of articles, both here and in the taxonomic treatments, and also in nomenclatural citations, the titles of serials are rendered in the forms recommended in G. D. R. Bridson and E. R. Smith (1991). When those forms are abbre- viated, as most are, cross references to the corresponding full serial titles are interpolated here alphabetically by abbreviated form. In nomenclatural citations (only), book titles are rendered in the abbreviated forms recommended in F. A. Stafleu and R. S. Cowan (1976–1988) and F. A. Stafleu and E. A. Mennega (1992+). Here, those abbreviated forms are indicated parenthetically following the full citations of the corresponding works, and cross references to the full citations are interpolated in the list alphabetically by abbreviated form. Two or more works published in the same year by the same author or group of coauthors will be distinguished uniquely and consistently throughout all volumes of Flora of North America by lower-case letters (b, c, d, ...) suffixed to the date for the second and subsequent works in the set. The suffixes are assigned in order of editorial encounter and do not reflect chronological sequence of publication. The first work by any particular author or group from any given year carries the implicit date suffix “a”; thus, the sequence of explicit suffixes begins with “b”. Works missing from any suffixed sequence here are ones cited elsewhere in the Flora that are not pertinent in these volumes. -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist WATER INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 0908 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 1 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 8 IBI sample collection ............................................. 8 Habitat measures............................................... 10 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 15 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 19 Designation of guilds....................................... 20 Results and discussion................................................ 22 Sampling sites and collection results . 22 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 41 1. Number of native species ................................ -

Endangered Species Act Section 7 Consultation Final Programmatic

Endangered Species Act Section 7 Consultation Final Programmatic Biological Opinion and Conference Opinion on the United States Department of the Interior Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement’s Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act Title V Regulatory Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ecological Services Program Division of Environmental Review Falls Church, Virginia October 16, 2020 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................3 2 Consultation History .........................................................................................................4 3 Background .......................................................................................................................5 4 Description of the Action ...................................................................................................7 The Mining Process .............................................................................................................. 8 4.1.1 Exploration ........................................................................................................................ 8 4.1.2 Erosion and Sedimentation Controls .................................................................................. 9 4.1.3 Clearing and Grubbing ....................................................................................................... 9 4.1.4 Excavation of Overburden and Coal ................................................................................ -

THE GENETIC DIVERSITY and POPULATION STRUCTURE of GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS of NATURAL HISTORY and CONSERVATION EFFORTS a Thesis B

THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS A Thesis by NIKOLAI M. HAY Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2017 Department of Biology ! THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS A Thesis by NIKOLAI M. HAY December 2017 APPROVED BY: Matt C. Estep Chairperson, Thesis Committee Zack E. Murrell Member, Thesis Committee Ray Williams Member, Thesis Committee Zack E Murrell Chairperson, Department of Biology Max C. Poole, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies ! Copyright by Nikolai M. Hay 2017 All Rights Reserved ! Abstract THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS Nikolai M. Hay B.S., Appalachian State University M.S., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Matt C. Estep Geum radiatum is a federally endangered high-elevation rock outcrop endemic herb that is widely recognized as a hexaploid and a relic species. Little is currently known about G. radiatum genetic diversity, population interactions, or the effect of augmentations. This study sampled every known population of G. radiatum and used microsatellite markers to observe the alleles present at 8 loci. F-statistics, STRUCTURE, GENODIVE, and the R package polysat were used to measure diversity and genetic structure. The analysis demonstrates that there is interconnectedness and structure of populations and was able to locate augmented and punitive hybrids individuals within an augmented population. Geum radiautm has diversity among and between populations and suggests current gene flow in the northern populations. -

Section 4.2.2.2

4.0 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS 4.1 GEOLOGY 4.1.1 Existing Resources 4.1.1.1 Geologic Setting The proposed LX Project is located entirely in the Kanawha Section of the Appalachian Plateaus physiographic province. The Appalachian Plateaus consist primarily of Pennsylvanian and Permian layered deposits, with Quaternary Alluvium overlying most geologic formations (USGS, 2015a). Elevations along the project range from 455 feet to 1,500 feet above mean sea level (USGS, 2015b). Topography in the project area ranges from relatively flat-lying rocks and rolling hills to steep slopes, with a local relief of up to several hundred feet (West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey [WVGES], 2004a; Greene County Government, 2013; ODNR, 2014a). The proposed RXE Project Grayson CS is located in the region known as the Eastern Kentucky Coal Field (Kentucky Geological Survey [KGS], 2012a), in an area of Quaternary alluvium composed of sand, silt, clay, and gravel created by floodplain deposits of present day streams. The thickness of the alluvium ranges from 0 to 60 feet (Whittington and Ferm, 1967). The proposed RXE Project Means CS is located within the Lexington Plains Section of the Interior Low Plateaus physiographic province (USGS, 2015a), in a region known as The Knobs, that consists of hundreds of isolated, steep-sloping, cone-shaped hills (KGS, 2012b). The nearest knob, Kashs Knob, is approximately one-quarter mile north of the proposed compressor station site (USGS, 1975). The USDA Soil Conservation Survey (SCS) County soil survey information indicates there are restrictive layers (potentially shallow bedrock) within the upper five feet of the ground surface at both CS locations (USDA SCS, 1974 and 1983). -

2020-04-10 Draft Tande Species Desktop Assessment Report

600 North 18th Street Hydro Services 16N-8180 Birmingham, AL 35203 205 257 2251 tel [email protected] April 10, 2020 VIA ELECTRONIC FILING Project No. 2628-065 R.L. Harris Hydroelectric Project Transmittal of the Draft Threatened and Endangered Species Desktop Assessment Ms. Kimberly D. Bose Secretary Federal Energy Regulatory Commission 888 First Street N. Washington, DC 20426 Dear Secretary Bose, Alabama Power Company (Alabama Power) is the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC or Commission) licensee for the R.L. Harris Hydroelectric Project (Harris Project) (FERC No. 2628-065). On April 12, 2019, FERC issued its Study Plan Determination1 (SPD) for the Harris Project, approving Alabama Power’s ten relicensing studies with FERC modifications. On May 13, 2019, Alabama Power filed Final Study Plans to incorporate FERC’s modifications and posted the Final Study Plans on the Harris relicensing website at www.harrisrelicensing.com. In the Final Study Plans, Alabama Power proposed a schedule for each study that included filing a voluntary Progress Update in October 2019 and October 2020. Alabama Power filed the first of two Progress Updates on October 31, 2019.2 Pursuant to the Commission’s Integrated Licensing Process (ILP) and 18 CFR § 5.15(c), Alabama Power filed its Harris Project Initial Study Report (ISR) on April 10,2020. Concurrently, and consistent with FERC’s April 12, 2019 SPD, Alabama Power is filing the Draft Threatened and Endangered Species Desktop Assessment (Draft Assessment) (Attachment 1). This filing also includes the stakeholder consultation for this study beginning May 2019 through March 2020 (Attachment 2). Stakeholders have until June 11, 2020 to submit their comments to Alabama Power on the Draft Assessment. -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist ECOSYSTEMS INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 1210 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 2 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 9 IBI sample collection ............................................. 9 Habitat measures............................................... 11 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 16 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 20 Designation of guilds....................................... 21 Results and discussion................................................ 23 Sampling sites and collection results . 23 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 48 Metrics selected for the -

Threatened and Endangered Species List

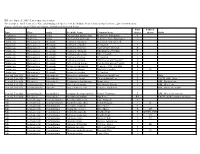

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

![Kyfishid[1].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2624/kyfishid-1-pdf-1462624.webp)

Kyfishid[1].Pdf

Kentucky Fishes Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission To conserve, protect and enhance Kentucky’s fish and wildlife resources and provide outstanding opportunities for hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, shooting sports, wildlife viewing, and related activities. Federal Aid Project funded by your purchase of fishing equipment and motor boat fuels Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission Kentucky Fishes by Matthew R. Thomas Fisheries Program Coordinator 2011 (Third edition, 2021) Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources Division of Fisheries Cover paintings by Rick Hill • Publication design by Adrienne Yancy Preface entucky is home to a total of 245 native fish species with an additional 24 that have been introduced either intentionally (i.e., for sport) or accidentally. Within Kthe United States, Kentucky’s native freshwater fish diversity is exceeded only by Alabama and Tennessee. This high diversity of native fishes corresponds to an abun- dance of water bodies and wide variety of aquatic habitats across the state – from swift upland streams to large sluggish rivers, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. Approximately 25 species are most frequently caught by anglers either for sport or food. Many of these species occur in streams and rivers statewide, while several are routinely stocked in public and private water bodies across the state, especially ponds and reservoirs. The largest proportion of Kentucky’s fish fauna (80%) includes darters, minnows, suckers, madtoms, smaller sunfishes, and other groups (e.g., lam- preys) that are rarely seen by most people. -

Etheostoma Maydeni) Species Status Assessment

Redlips Darter (Etheostoma maydeni) Species Status Assessment Version 1.1 Photo courtesy of Dr. David Neely, Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute (East Fork Obey River, Fentress County, Tennessee, December 2017) U.S Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4 Atlanta, Georgia May 2018 Redlips Darter SSA This document was prepared by Dr. Michael A. Floyd, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Kentucky Ecological Services Field Office, Frankfort, Kentucky. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service greatly appreciates the assistance of Tom Barbour (Kentucky Division of Mine Permits), Darrell Bernd (Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA)), Davy Black (Eastern Kentucky University), Stephanie Brandt (Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources (KDFWR)), Bart Carter (TWRA), Stephanie Chance (USFWS – Tennessee Ecological Services Field Office (TFO)), Brian Evans (USFWS – Atlanta), Mike Compton (Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission (KSNPC)), Dr. Bernie Kuhajda (Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute (TNACI), Pam Martin (U.S. Forest Service - Daniel Boone National Forest (DBNF)), Matt Moran (U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement), Dr. Dave Neely (TNACI), Dr. Steve Powers (Roanoke College), Pat Rakes (Conservation Fisheries, Inc. (CFI)), Rebecca Schapansky (National Park Service – Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area), J.R. Shute (CFI), Jeff Simmons (Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)), Justin Spaulding (TWRA), Kurt Snider (USFWS – TFO), Dr. Matthew Thomas (KDFWR), Keith Wethington (KDFWR), David Withers (Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC)), and Brian Zimmerman (The Ohio State University), who provided helpful information and/or review of the draft document. Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Redlips Darter (Etheostoma maydeni) Species Status Assessment, Version 1.1. May 2018. -

Status of the Flame Chub Hemitremia Flammea in Alabama, USA

Vol. 12: 87–93, 2010 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online July 19 doi: 10.3354/esr00283 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Status of the flame chub Hemitremia flammea in Alabama, USA Bruce Stallsmith* Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, Alabama 35899, USA ABSTRACT: The status of many freshwater fish species in the species-rich southeastern United States is surprisingly poorly known. Vulnerable species found in smaller streams in the region have not received adequate research attention. The flame chub Hemitremia flammea (Cyprinidae) is included among a group of stream species considered to be ‘narrow endemics’ susceptible to habitat alterations due to growing human population. The obligatory habitat is spring-fed streams sensitive to human activities. The species has a patchy range primarily in the Tennessee River Valley in Alabama and Tennessee, USA. The conservation status of the flame chub is poorly documented. The NatureServe global status of the flame chub is G3, Vulnerable, and the Alabama state status is S3, Vulnerable. Reflecting the poor knowledge of the species’ status, the International Union for the Con- servation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Category is DD (Data Deficient), a change from an earlier listing of Rare. This study is intended as a presence or absence survey of flame chubs at historic location sites in north Alabama based on holdings records of the University of Alabama Ichthyology Collec- tion in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Fifty-three sites in 9 counties in the Tennessee River drainage with a historic record of flame chub presence were visited and sampled by seining. One or more flame chubs were found at 18 of these sites.