Geoffrey Knight and His Contribution to Psychosurgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical Order by Description IICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetic Order by Description Note: SSIS stores ICD-10 code descriptions up to 100 characters. Actual code description can be longer than 100 characters. ICD-10 Diagnosis Code ICD-10 Diagnosis Description F40.241 Acrophobia F41.0 Panic Disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) F43.0 Acute stress reaction F43.22 Adjustment disorder with anxiety F43.21 Adjustment disorder with depressed mood F43.24 Adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct F43.23 Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood F43.25 Adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct F43.29 Adjustment disorder with other symptoms F43.20 Adjustment disorder, unspecified F50.82 Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder F51.02 Adjustment insomnia F98.5 Adult onset fluency disorder F40.01 Agoraphobia with panic disorder F40.02 Agoraphobia without panic disorder F40.00 Agoraphobia, unspecified F10.180 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced anxiety disorder F10.14 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced mood disorder F10.150 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions F10.151 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations F10.159 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder, unspecified F10.181 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sexual dysfunction F10.182 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sleep disorder F10.121 Alcohol abuse with intoxication delirium F10.188 Alcohol -

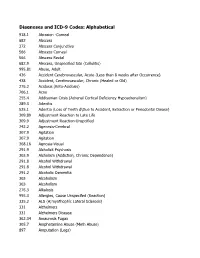

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

Deep Brain Stimulation in Psychiatric Practice

Clinical Memorandum Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice March 2018 Authorising Committee/Department: Board Responsible Committee/Department: Section of Electroconvulsive Therapy and Neurostimulation Document Code: CLM PPP Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) has developed this clinical memorandum to inform psychiatrists who are involved in using DBS as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Clinical trials into the use of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) to treat psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorders, and anorexia are occurring worldwide, including within Australia. Although overall the existing literature shows promise for DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, its use is still an emerging treatment and requires a stronger clinical evidence base of randomised control trials to develop a substantial body of evidence to identify and support its efficacy (Widge et al., 2016; Barrett, 2017). The RANZCP supports further research and clinical trials into the use of DBS for psychiatric disorders and acknowledges that it has potential application as a treatment for appropriately selected patients. Background DBS is an established treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia, and has also been used in the control of movement disorder associated with severe and medically intractable Tourette syndrome (Cannon et al., 2012). In Australia the Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved devices for DBS. It is eligible for reimbursement under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease but not for other neurological or psychiatric disorders. As the use of DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders is emerging, it is currently only available in speciality clinics or hospitals under research settings. -

Glossary of Psychological Terms

Glossary of Psychological Terms From Gerrig, Richard J. & Philip G. Zimbardo. Psychology And Life, 16/e Published by Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA. Copyright (c) 2002 by Pearson Education. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. http://www.apa.org/research/action/glossary.aspx#b ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPRSTUVWYZ A A-B-A design Experimental design in which participants first experience the baseline condition (A), then experience the experimental treatment (B), and then return to the baseline (A). Abnormal psychology The area of psychological investigation concerned with understanding the nature of individual pathologies of mind, mood, and behavior. Absolute threshold The minimum amount of physical energy needed to produce a reliable sensory experience; operationally defined as the stimulus level at which a sensory signal is detected half the time. Accommodation The process by which the ciliary muscles change the thickness of the lens of the eye to permit variable focusing on near and distant objects. Accommodation According to Piaget, the process of restructuring or modifying cognitive structures so that new information can fit into them more easily; this process works in tandem with assimilation. Acquisition The stage in a classical conditioning experiment during which the conditioned response is first elicited by the conditioned stimulus. Action potential The nerve impulse activated in a neuron that travels down the axon and causes neurotransmitters to be released into a synapse. Acute stress A transient state of arousal with typically clear onset and offset patterns. Addiction A condition in which the body requires a drug in order to function without physical and psychological reactions to its absence; often the outcome of tolerance and dependence. -

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Psychiatric Disorders

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research City College of New York 2015 Transcranial direct current stimulation in psychiatric disorders Gabriel Tortella University of São Paulo Roberta Casati Università degli Studi Milano Bicocca Luana V M Aparicio University of São Paulo Antonio Mantovani CUNY City College Natasha Senço University of São Paulo See next page for additional authors How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_pubs/658 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Authors Gabriel Tortella, Roberta Casati, Luana V M Aparicio, Antonio Mantovani, Natasha Senço, Giordano D'Urso, Jerome Brunelin, Fabiana Guarienti, Priscila Mara Lorencini Selingardi, Débora Muszkat, Bernardo de Sampaio Pereira Junior, Leandro Valiengo, Adriano H. Moffa, Marcel Simis, Lucas Borrione, and Andre R. Brunoni This article is available at CUNY Academic Works: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_pubs/658 World Journal of W J P Psychiatry Submit a Manuscript: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/ World J Psychiatr 2015 March 22; 5(1): 88-102 Help Desk: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/helpdesk.aspx ISSN 2220-3206 (online) DOI: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.88 © 2015 Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved. REVIEW Transcranial direct current stimulation in psychiatric disorders Gabriel Tortella, Roberta Casati, Luana V M Aparicio, -

Dsm-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders Anorexia Nervosa

DSM-5 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR EATING DISORDERS ANOREXIA NERVOSA DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA To be diagnosed with anorexia nervosa according to the DSM-5, the following criteria must be met: 1. Restriction of energy intaKe relative to requirements leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. 2. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight. 3. Disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight. Even if all the DSM-5 criteria for anorexia are not met, a serious eating disorder can still be present. Atypical anorexia includes those individuals who meet the criteria for anorexia but who are not underweight despite significant weight loss. Research studies have not found a difference in the medical and psychological impacts of anorexia and atypical anorexia. BULIMIA NERVOSA DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA According to the DSM-5, the official diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa are: • Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following: o Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g. within any 2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances. o A sense of lacK of control over eating during the episode (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). -

Patients' and Carers' Perspectives of Psychopharmacological

Chapter Patients’ and Carers’ Perspectives of Psychopharmacological Interventions Targeting Anorexia Nervosa Symptoms Amabel Dessain, Jessica Bentley, Janet Treasure, Ulrike Schmidt and Hubertus Himmerich Abstract In clinical practice, patients with anorexia nervosa (AN), their carers and clini- cians often disagree about psychopharmacological treatment. We developed two corresponding questionnaires to survey the perspectives of patients with AN and their carers on psychopharmacological treatment. These questionnaires were dis- tributed to 36 patients and 37 carers as a quality improvement project on a specialist unit for eating disorders at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Although most patients did not believe that medication could help with AN, the majority thought that medication for AN should help with anxiety (61.1%), con- centration (52.8%), sleep problems (52.8%) and anorexic thoughts (55.6%). Most of the carers shared the view that drug treatment for AN should help with anxiety (54%) and anorexic thoughts (64.8%). Most patients had concerns about potential weight gain, increased appetite, changes in body shape and metabolism during psychopharmacological treatment. By contrast, the majority of carers were not concerned about these specific side effects. Some of the concerns expressed by the patients seem to be AN-related. However, their desire for help with anxiety and anorexic thoughts, which is shared by their carers, should be taken seriously by clinicians when choosing a medication or planning psychopharmacological studies. Keywords: anorexia nervosa, psychopharmacological treatment, treatment effects, side effects, opinion survey, patients, carers 1. Introduction 1.1 Anorexia nervosa Anorexia nervosa (AN) is an eating disorder. According to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1], its diagnostic criteria are significantly low body weight, intense fear of weight gain, and disturbed body perception. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

Glossary of Terms for Psychiatric Drugs

GLOSSARY OF TERMS Citizens Commission on Human Rights 6616 Sunset Blvd, Los Angeles, CA. USA 90028 Telephone: (323) 467-4242 Fax: (323) 467-3720 E-mail: [email protected] www.cchr.org GLOSSARY OF TERMS ADDICTIVE: a drug, especially an illegal one or a activity: being lively, active; disorder: a condition psychotropic (mind-altering) prescription drug, that that has no physical basis but the diagnosis of which creates a state of physical or mental dependence or relies upon observing symptoms of behavior. These one liable to have a damaging effect. behaviors include: has too little attention, is too active, fidgets, squirms, fails to complete homework ADRENALINE: a hormone secreted by the inner or chores, climbs or talks excessively, loses pencils or part of the adrenal glands, which speeds up the toys and interrupts others. heartbeat and thereby increases bodily energy and resistance to fatigue. ATYPICAL: new, not typical, not like the usual or normal type. An atypical drug could be a new AKATHISIA: a, meaning “without” and kathisia, antidepressant or antipsychotic as opposed to older meaning “sitting,” an inability to keep still. Patients ones of the same class. The term atypical was used pace about uncontrollably. The side effect has been to market newer drugs as having fewer side effects linked to assaultive, violent behavior. than older drugs of the same class.Thorazine is a typical antipsychotic; Zyprexa is an atypical. Elavil AMPHETAMINES: any group of powerful drugs, or Remeron are typical antidepressants, Prozac and called stimulants, that act on the central nervous Zoloft are atypicals. system (the brain and the spinal cord), to increase heart rate and blood pressure and reduce fatigue. -

Psychosurgery: Review of Latest Concepts and Applications

Review 29 Psychosurgery: Review of Latest Concepts and Applications Sabri Aydin 1 Bashar Abuzayed 1 1 Department of Neurosurgery, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul Address for correspondence and reprint requests Bashar Abuzayed, University, Istanbul, Turkey M.D., Department of Neurosurgery, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul University, K.M.P. Fatih, Istanbul 34089, Turkey J Neurol Surg A 2013;74:29–46. (e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract Although the utilization of psychosurgery has commenced in early 19th century, when compared with other neurosurgical fields, it faced many obstacles resulting in the delay of advancement of this type of surgical methodology. This was due to the insufficient knowledge of both neural networks of the brain and the pathophysiology of psychiatric diseases. The aggressive surgical treatment modalities with high mortality and morbid- ity rates, the controversial ethical concerns, and the introduction of antipsychotic drugs were also among those obstacles. With the recent advancements in the field of neuroscience more accurate knowledge was gained in this fieldofferingnewideas for the management of these diseases. Also, the recent technological developments Keywords aided the surgeons to define more sophisticated and minimally invasive techniques ► deep brain during the surgical procedures. Maybe the most important factor in the rerising of stimulation psychosurgery is the assemblage of the experts, clinicians, and researchers in various ► neural networks fields of neurosciences implementing a multidisciplinary approach. In this article, the ► neuromodulation authors aim to review the latest concepts of the pathophysiology and the recent ► psychiatric disorders advancements of the surgical treatment of psychiatric diseases from a neurosurgical ► psychosurgery point of view. Introduction omy in 1935.8,22 Moniz's initial trial resulted in no deaths or serious morbidities, which were seen in the other treat- Psychosurgery existed long before the advent of the frontal ments available for psychological disorders, such as insulin lobotomy. -

Eating Disorder Consultant Psychiatrist Job Description for CR174 Revision

Eating Disorder Consultant Psychiatrist Job Description for CR174 Revision Introduction Eating Disorders (ED) are a group of very complex Psychiatric Disorders and include Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorders and Atypical Eating Disorders. The complexity of these disorders can be gauged from the fact that at 12 months only fifty percent of adolescents with anorexia nervosa go in remission and only 40 % of patients with bulimia nervosa go in remission by six months, with relapse common. Research indicates childhood onset of ED carries a high risk of continuity in adulthood. Hospitalisation of patients with ED appears to be associated with worse prognosis; the number of patients with eating disorders who needed hospitalisation has doubled in last three years. More than six out of every ten people with ED suffer from other psychiatric co-morbidities such as depression, anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). People with ED carry the highest risk of mortality among all the psychiatric disorders because of significant level of medical complexities associated with restriction of food intake. Patients with ED also carry higher risks of self-harm and suicide. People with Eating Disorders display a distorted attitude towards eating, weight and shape and may have irrational fear of becoming fat. The treatment of Eating disorders involves offering the patients individual and family based therapies, management of their physical and psychiatric risks and offering them nutritional support. The Consultant Psychiatrists with their comprehensive Psychiatric, Medical and Psychological training offer clinical leadership to Eating Disorder Services teams to deliver high quality care to patients who suffer from Eating Disorders and have very complex needs.