Paleoanthropological Methods: Dating Fossils "Archaeologists Will Date Any Old Thing" (Jim Moore, UCSD)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Time Two Ways to Date Geologic Events Steno's Laws

Frank Press • Raymond Siever • John Grotzinger • Thomas H. Jordan Understanding Earth Fourth Edition Chapter 10: The Rock Record and the Geologic Time Scale Lecture Slides prepared by Peter Copeland • Bill Dupré Copyright © 2004 by W. H. Freeman & Company Geologic Time Two Ways to Date Geologic Events A major difference between geologists and most other 1) relative dating (fossils, structure, cross- scientists is their concept of time. cutting relationships): how old a rock is compared to surrounding rocks A "long" time may not be important unless it is greater than 1 million years 2) absolute dating (isotopic, tree rings, etc.): actual number of years since the rock was formed Steno's Laws Principle of Superposition Nicholas Steno (1669) In a sequence of undisturbed • Principle of Superposition layered rocks, the oldest rocks are • Principle of Original on the bottom. Horizontality These laws apply to both sedimentary and volcanic rocks. Principle of Original Horizontality Layered strata are deposited horizontal or nearly horizontal or nearly parallel to the Earth’s surface. Fig. 10.3 Paleontology • The study of life in the past based on the fossil of plants and animals. Fossil: evidence of past life • Fossils that are preserved in sedimentary rocks are used to determine: 1) relative age 2) the environment of deposition Fig. 10.5 Unconformity A buried surface of erosion Fig. 10.6 Cross-cutting Relationships • Geometry of rocks that allows geologists to place rock unit in relative chronological order. • Used for relative dating. Fig. 10.8 Fig. 10.9 Fig. 10.9 Fig. 10.9 Fig. Story 10.11 Fig. -

Lab 7: Relative Dating and Geological Time

LAB 7: RELATIVE DATING AND GEOLOGICAL TIME Lab Structure Synchronous lab work Yes – virtual office hours available Asynchronous lab work Yes Lab group meeting No Quiz None – Test 2 this week Recommended additional work None Required materials Pencil Learning Objectives After carefully reading this chapter, completing the exercises within it, and answering the questions at the end, you should be able to: • Apply basic geological principles to the determination of the relative ages of rocks. • Explain the difference between relative and absolute age-dating techniques. • Summarize the history of the geological time scale and the relationships between eons, eras, periods, and epochs. • Understand the importance and significance of unconformities. • Explain why an understanding of geological time is critical to both geologists and the general public. Key Terms • Eon • Original horizontality • Era • Cross-cutting • Period • Inclusions • Relative dating • Faunal succession • Absolute dating • Unconformity • Isotopic dating • Angular unconformity • Stratigraphy • Disconformity • Strata • Nonconformity • Superposition • Paraconformity Time is the dimension that sets geology apart from most other sciences. Geological time is vast, and Earth has changed enough over that time that some of the rock types that formed in the past could not form Lab 7: Relative Dating and Geological Time | 181 today. Furthermore, as we’ve discussed, even though most geological processes are very, very slow, the vast amount of time that has passed has allowed for the formation of extraordinary geological features, as shown in Figure 7.0.1. Figure 7.0.1: Arizona’s Grand Canyon is an icon for geological time; 1,450 million years are represented by this photo. -

Paleomagnetism and U-Pb Geochronology of the Late Cretaceous Chisulryoung Volcanic Formation, Korea

Jeong et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2015) 67:66 DOI 10.1186/s40623-015-0242-y FULL PAPER Open Access Paleomagnetism and U-Pb geochronology of the late Cretaceous Chisulryoung Volcanic Formation, Korea: tectonic evolution of the Korean Peninsula Doohee Jeong1, Yongjae Yu1*, Seong-Jae Doh2, Dongwoo Suk3 and Jeongmin Kim4 Abstract Late Cretaceous Chisulryoung Volcanic Formation (CVF) in southeastern Korea contains four ash-flow ignimbrite units (A1, A2, A3, and A4) and three intervening volcano-sedimentary layers (S1, S2, and S3). Reliable U-Pb ages obtained for zircons from the base and top of the CVF were 72.8 ± 1.7 Ma and 67.7 ± 2.1 Ma, respectively. Paleomagnetic analysis on pyroclastic units yielded mean magnetic directions and virtual geomagnetic poles (VGPs) as D/I = 19.1°/49.2° (α95 =4.2°,k = 76.5) and VGP = 73.1°N/232.1°E (A95 =3.7°,N =3)forA1,D/I = 24.9°/52.9° (α95 =5.9°,k =61.7)and VGP = 69.4°N/217.3°E (A95 =5.6°,N=11) for A3, and D/I = 10.9°/50.1° (α95 =5.6°,k = 38.6) and VGP = 79.8°N/ 242.4°E (A95 =5.0°,N = 18) for A4. Our best estimates of the paleopoles for A1, A3, and A4 are in remarkable agreement with the reference apparent polar wander path of China in late Cretaceous to early Paleogene, confirming that Korea has been rigidly attached to China (by implication to Eurasia) at least since the Cretaceous. The compiled paleomagnetic data of the Korean Peninsula suggest that the mode of clockwise rotations weakened since the mid-Jurassic. -

Scientific Dating of Pleistocene Sites: Guidelines for Best Practice Contents

Consultation Draft Scientific Dating of Pleistocene Sites: Guidelines for Best Practice Contents Foreword............................................................................................................................. 3 PART 1 - OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 3 The Quaternary stratigraphical framework ........................................................................ 4 Palaeogeography ........................................................................................................... 6 Fitting the archaeological record into this dynamic landscape .............................................. 6 Shorter-timescale division of the Late Pleistocene .............................................................. 7 2. Scientific Dating methods for the Pleistocene ................................................................. 8 Radiometric methods ..................................................................................................... 8 Trapped Charge Methods................................................................................................ 9 Other scientific dating methods ......................................................................................10 Relative dating methods ................................................................................................10 -

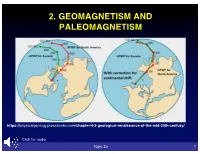

2. Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism

2-1 2. GEOMAGNETISM AND PALEOMAGNETISM 1 https://physicalgeology.pressbooks.com/chapter/4-3-geological-renaissance-of-the-mid-20th-century/ 2 2-2 ELECTRIC q Q FIELD q -Q 3 MAGNETIC DIPOLE Although magnetic fields have a similar form to electric fields, they differ because there are no single magnetic "charges," known as magnetic poles. Hence the fundamental entity is the magnetic dipole arising from an electric current I circulating in a conducting loop, such as a wire, with area A . The field is described as resulting from a magnetic dipole characterized by a dipole moment m Magnetic dipoles can arise from electric currents - which are moving electric charges - on scales ranging from wire loops to the hot fluid moving in the core that generates the earth’s magnetic field. They also arise at the atomic level, where they are intrinsic properties of charged particles like protons and electrons. As a result, rocks can be magnetized, much like familiar bar magnets. Although the magnetism of a bar magnet arises from the electrons within it, it can be viewed as a magnetic dipole, with north and south magnetic poles at opposite ends. 4 2-3 MAGNETIC FIELD 5 We visualize the magnetic field of a dipole in terms of magnetic field lines pointing outward from the north pole of a bar magnet and in toward the south. The lines point in the direction another bar magnet, such as a compass needle, would point. At any point, the north pole of the compass needle would point along the DIPOLE field line, toward the south pole MAGNETIC of the bar magnet. -

Personal Details: Relative Dating Methods Archaeology; Principles

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Archaeology; Principles and Methods Relative Dating Methods Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. K.P. Rao University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad. Prof. K. Rajan Pondicherry University, Pondicherry. Prof. R. N. Singh Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Archaeology; Principles and Methods Module Name/Title Relative Dating Methods Module Id IC / APM / 17 Pre requisites Objectives Archaeology / Stratigraphy / Dating / Keywords Geochronology E-Text (Quadrant-I) : 1. Introduction In archaeology, the material unearthed in the excavations and archaeological remains surfaced and documented in the explorations are dated by following two methods namely, absolute dating method and relative dating method. In the former method, the artefacts are being preciously dated using various scientific techniques and in a few cases it is dated based on the hidden historical data available with historical documents such as inscriptions, copper plates, seals, coins, inscribed portrait sculptures and monuments. In the latter method, a tentative date is achieved based on archaeological stratigraphy, seriation, palaeography, linguistic style, context, art and architectural features. Though the absolute dates are the most desirable one, the significance of relative dates increases manifold when the absolute dates are not available. Till advent of the scientific techniques, most of the archaeological and historical objects were dated based on relative dating methods. Archaeologists are resorted to the use of relative dating techniques when the absolute dates are not possible or feasible. Estimation of the age was merely a guess work in the initial stage of archaeological investigation particularly in 18th-19th centuries. -

2. Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism

2. GEOMAGNETISM AND PALEOMAGNETISM https://physicalgeology.pressbooks.com/chapter/4-3-geological-renaissance-of-the-mid-20th-century/ Click for audio Topic 2a 1 Topic 2a 2 q Q ELECTRIC FIELD q -Q Topic 2a 3 MAGNETIC DIPOLE Although magnetic fields have a similar form to electric fields, they differ because there are no single magnetic "charges," known as magnetic poles. Hence the fundamental entity is the magnetic dipole arising from an electric current I circulating in a conducting loop, such as a wire, with area A . The field is described as resulting from a magnetic dipole characterized by a dipole moment m Magnetic dipoles can arise from electric currents - which are moving electric charges - on scales ranging from wire loops to the hot fluid moving in the core that generates the earth’s magnetic field. They also arise at the atomic level, where they are intrinsic properties of charged particles like protons and electrons. As a result, rocks can be magnetized, much like familiar bar magnets. Although the magnetism of a bar magnet arises from the electrons within it, it can be viewed as a magnetic dipole, with north and south magnetic poles at opposite ends. Topic 2a 4 Magnetic field B Units of B Tesla (T) = kg/s 2 -A A = Ampere (unit of current) Gauss (G) = 10-4 Tesla Gamma (! )= 10-9 Tesla = 1 nanoTesla (nT) Earth’s field is about 50 "T = 50 x 10-6 Tesla Topic 2a 5 We visualize the magnetic field of a dipole in terms of magnetic field lines pointing outward from the north pole of a bar magnet and in toward the south. -

Earth Science Power Standards

Macomb Intermediate School District High School Science Power Standards Document Earth Science The Michigan High School Science Content Expectations establish what every student is expected to know and be able to do by the end of high school. They also outline the parameters for receiving high school credit as dictated by state law. To aid teachers and administrators in meeting these expectations the Macomb ISD has undertaken the task of identifying those content expectations which can be considered power standards. The critical characteristics1 for selecting a power standard are: • Endurance – knowledge and skills of value beyond a single test date. • Leverage - knowledge and skills that will be of value in multiple disciplines. • Readiness - knowledge and skills necessary for the next level of learning. The selection of power standards is not intended to relieve teachers of the responsibility for teaching all content expectations. Rather, it gives the school district a common focus and acts as a safety net of standards that all students must learn prior to leaving their current level. The following document utilizes the unit design including the big ideas and real world contexts, as developed in the science companion documents for the Michigan High School Science Content Expectations. 1 Dr. Douglas Reeves, Center for Performance Assessment Unit 1: Organizing Principles of Earth Science Big Idea Processes, events and features on Earth result from energy transfer and movement of matter through interconnected Earth systems. Contextual Understandings Earth science is an umbrella term for the scientific disciplines of geology, meteorology, climatology, hydrology, oceanography, and astronomy. Earth systems science has given an improved, interdisciplinary perspective to researchers in fields concerned with global change, such as climate change and geologic history. -

Stage 1А–Аdesired Results

www.nextgenscience.org STAGE 1 – DESIRED RESULTS Unit Title: Earth’s Place in the Universe Grade Level: 6 Length/Timing of Unit: Teacher(s)/Designer(s): Pascack Valley Regional Science Committee Science State standards addressed (verbatim): MSESS11 . Develop and use a model of the Earthsunmoon system to describe the cyclic patterns of lunar phases, eclipses of the sun and moon, and seasons. [Clarification Statement: Examples of models can be physical, graphical, or conceptual.] MSESS12. Develop and use a model to describe the role of gravity in the motions within galaxies and the solar system. [Clarification Statement: Emphasis for the model is on gravity as the force that holds together the solar system and Milky Way galaxy and controls orbital motions within them. Examples of models can be physical (such as the analogy of distance along a football field or computer visualizations of elliptical orbits) or conceptual (such as mathematical proportions relative to the size of familiar objects such as students’ school or state).] [Assessment Boundary: Assessment does not include Kepler’s Laws of orbital motion or the apparent retrograde motion of the planets as viewed from Earth.] MSESS13. Analyze and interpret data to determine scale properties of objects in the solar system. [Clarification Statement: Emphasis is on the analysis of data from Earthbased instruments, spacebased telescopes, and spacecraft to determine similarities and differences among solar system objects. Examples of scale properties include the sizes of an object’s layers (such as crust and atmosphere), surface features (such as volcanoes), and orbital radius. -

6. Relative and Absolute Dating

6. Relative and Absolute Dating Adapted by Sean W. Lacey & Joyce M. McBeth (2018) University of Saskatchewan from Deline B, Harris R, & Tefend K. (2015) "Laboratory Manual for Introductory Geology". First Edition. Chapter 1 "Relative and Absolute Dating" by Bradley Deline, CC BY-SA 4.0. View Source. 6.1 INTRODUCTION To develop a history of how geologic events have acted on the Earth through time, we need to understand what and when geological processes have occurred through Earth's history. Geologists learn about what processes occur on Earth through studying the rock record and observing geologic processes in modern environments. To understand when these processes have acted during Earth's geologic time, geologists make observations about the relationships of rocks to one another in the rock record, using a process called relative dating. Geologists use this information to construct models for how these relationships developed. For example, if the rock record in an area contains sedimentary rocks that are folded, a model to explain those relationships would start with a region where sediments were deposited, followed by lithification of the sediments to form rock, then the rocks would be subjected to tectonic pressures that folded the rocks. Using relative dating techniques, we know those events occurred in that order, but not when they occurred precisely in time. To add specific dates for the events in the model, geologists can use absolute dating techniques to date the rocks (determine their age). Geologists develop models such as this at locations all across Canada, North America, and around the globe. Each location geologists study may only provide information on Earth history from a short window in time; collectively, however, the information in these models can be used to develop our understanding of processes that have acted on Earth since it first formed. -

Relative Dating Unit B

Geologic Time Part I: Relative Dating Unit B Unit A James Hutton conceived of the Principle of Uniformitarianism at Sicar Point, Scotland in 1785. Think about how much time would pass to create the rock record shown above. What sequence of events would occur to produce the above record? Unit B Unit A 1. Deposition of sediment comprising Unit A (Sedimentation rates in the deep ocean range from .0005 - .001 mm per year). How long would it take to accumulate 200 meters of sediment?) 2. burial compaction & lithification of Unit A, 3. deformation (folding) of Unit A, 4. uplift and erosion of Unit A, 5. Deposition of sediment (Unit B), 6. burial compaction & lithification of Unit B, 7. deformation (folding) of Unit B, 8. uplift and erosion of Unit B. These geologic events require millions of years of time! Principle of Original Horizontality: Layered sedimentary rock is typically deposited horizontally, but can be deformed by tectonic processes. Can you think of a depositional environment where sedimentary layers are not deposited horizontally? Geologists use sedimentary structures to determine whether sedimentary layers or beds are right-side up, vertical or overturned. The Principle of Uniformitarianism states that the “present is the key to the past.” Those processes operating at the earth’s surface today are inferred to have operated in the past, such as the mudcracks forming in a playa lake today. Note the blowing sand in the background will fill in the cracks. The mudcracks shown above formed over 1.1 billion years ago in a dry lake basin are now found in Glacier National Park, Montana. -

Dating Techniques.Pdf

Dating Techniques Dating techniques in the Quaternary time range fall into three broad categories: • Methods that provide age estimates. • Methods that establish age-equivalence. • Relative age methods. 1 Dating Techniques Age Estimates: Radiometric dating techniques Are methods based in the radioactive properties of certain unstable chemical elements, from which atomic particles are emitted in order to achieve a more stable atomic form. 2 Dating Techniques Age Estimates: Radiometric dating techniques Application of the principle of radioactivity to geological dating requires that certain fundamental conditions be met. If an event is associated with the incorporation of a radioactive nuclide, then providing: (a) that none of the daughter nuclides are present in the initial stages and, (b) that none of the daughter nuclides are added to or lost from the materials to be dated, then the estimates of the age of that event can be obtained if the ration between parent and daughter nuclides can be established, and if the decay rate is known. 3 Dating Techniques Age Estimates: Radiometric dating techniques - Uranium-series dating 238Uranium, 235Uranium and 232Thorium all decay to stable lead isotopes through complex decay series of intermediate nuclides with widely differing half- lives. 4 Dating Techniques Age Estimates: Radiometric dating techniques - Uranium-series dating • Bone • Speleothems • Lacustrine deposits • Peat • Coral 5 Dating Techniques Age Estimates: Radiometric dating techniques - Thermoluminescence (TL) Electrons can be freed by heating and emit a characteristic emission of light which is proportional to the number of electrons trapped within the crystal lattice. Termed thermoluminescence. 6 Dating Techniques Age Estimates: Radiometric dating techniques - Thermoluminescence (TL) Applications: • archeological sample, especially pottery.