The Constitutionality of the NFL Patdown Policy After Sheehan and Johnston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salary Allocation and Risk Preferences in the National Football League

Salary Allocation and Risk Preferences in the National Football League: The Implications of Salary Allocation in Understanding the Preferences of NFL Owners Papa Chakravarthy Presented to the Department of Economics In partial fulfillment of the requirements For a Bachelor of Arts degree with Honors Harvard College Cambridge, Massachusetts March 8th, 2012 Abstract The study of risk preferences in the allocation of the National Football League’s salary cap has not seen much academic research. Previous analysis shows that the salary cap improves parity across the NFL and may be partially responsible for the growth of the United States’ most popular sports league. Allocating salary to players, however, can reveal a great deal of information regarding the utility function of NFL Owners. This paper illustrates, using data on wide receivers in the NFL from 2005 to 2009, variables predicting future performance in the NFL do not predict future salary, meaning Owners value something in addition to future expected performance when allocating salary. The potential to become a star, leadership or popularity may be the characteristic valued by Owners that is not shown by OLS regression. A comparison of NFL Owners to fantasy football owners shows that while the method of risk aversion differs between the two, it is impossible to rule out risk aversion by NFL Owners trying to retain aged players with high salaries. Finally, it is possible that NFL teams may improve team performance while staying within the salary cap by cutting players more frequently and signing shorter contracts, thus eliminating the need to overpay players and fielding a more competitive team. -

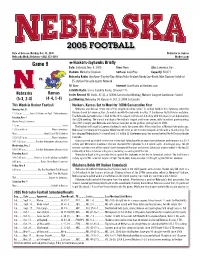

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Sept

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Sept. 12, 2005 Nebraska vs. Pittsburgh Nebraska Media Relations–(402) 472-2263 Huskers.com Game 3 8Huskers-Panthers Briefl y Date: Saturday, Sept. 17, 2005 Time: 2:36 p.m. Site: Lincoln, Neb. Stadium: Memorial Stadium Field: Tom Osborne Field Surface: FieldTurf (2005) vs. Capacity: 73,918 (271st Consecutive Sellout) Nebraska Radio: (Jim Rose–Play-by-Play; Adrian Fiala–Analyst; Randy Lee–Booth; Matt Davison–Sideline) 55-station Pinnacle Sports Network Nebraska Pittsburgh TV: ABC Regional (Brent Musburger-Play-by-Play; Gary Danielson-Color; Jack Arute-Sidelines) (2-0) (0-2) Internet: Live Radio on Huskers.com Satellite Radio: Sirius Satellite Radio, Channel 141 Special Events: Red Cross Appreciation Day This Week in Husker Football Nebraska Looks to Continue Season-Opening Momentum vs. Pitt Monday, Sept. 12 Fresh off two dominant defensive efforts, Nebraska will look to complete non-conference play unbeaten this Saturday when the Huskers play host to defending Big East Conference champion Pittsburgh at Memorial Stadium. 11:50 a.m. ............Coach Callahan on Big 12 Teleconference The game will kickoff at 2:36 p.m. and will be televised to a regional audience by ABC, with Brent Musburger, Gary Tuesday, Sept. 13 Danielson and Jack Arute on the call. Weekly Press Conference Nebraska is off to a 2-0 start thanks in large part to a tenacious Blackshirt defense. After recording school 11 a.m. ........................................................................ Lunch records for sacks and tackles for loss in the opener against Maine, the Husker defense continued its assault on the 11:30 a.m-Noon ......................................... -

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Oct

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Oct. 31, 2005 Nebraska vs. Kansas Nebraska Media Relations–(402) 472-2263 Huskers.com Game 9 8Huskers-Jayhawks Briefl y Date: Saturday, Nov. 5, 2005 Time: Noon Site: Lawrence, Kan. Stadium: Memorial Stadium Surface: AstroPlay Capacity: 50,071 Nebraska Radio: (Jim Rose–Play-by-Play; Adrian Fiala–Analyst; Randy Lee–Booth; Matt Davison–Sideline) vs. 55-station Pinnacle Sports Network TV: None Internet: Live Radio on Huskers.com Satellite Radio: Sirius Satellite Radio, Channel 123 Nebraska Kansas Series Record: NU leads, 87-21-3 (100th Consecutive Meeting, Nation’s Longest Continuous Series) (5-3, 2-3) (4-4, 1-4) Last Meeting: Nebraska 14, Kansas 8, Oct. 2, 2004, in Lincoln This Week in Husker Football Huskers, Kansas Set to Meet for 100th Consecutive Year Monday, Oct. 31 Nebraska and Kansas renew one of the longest-standing series’ in college football this Saturday, when the 11:50 a.m. ............Coach Callahan on Big 12 Teleconference Huskers travel to Lawrence, Kan., to match up with the Jayhawks in a Big 12 Conference North Division matchup. The Nebraska-Jayhawk series is tied for the third-longest in Division I-A history, with this week’s matchup marking Tuesday, Nov. 1 the 112th meeting. The annual matchup is the nation’s longest continuous series, with Saturday’s game marking Weekly Press Conference the 100th straight year Nebraska and Kansas have met on the gridiron, dating back to 1906. 11 a.m. ........................................................................ Lunch The Huskers will travel to Lawrence looking to end a two-game slide. After a road loss at Missouri two weeks ago, 11:30 a.m-Noon ......................................... -

Subverting the Male Gaze in Televised Sports Performances Shannon L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Unsportsman-like Conduct: Subverting the Male Gaze in Televised Sports Performances Shannon L. Walsh Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF THEATRE UNSPORTSMAN-LIKE CONDUCT: SUBVERTING THE MALE GAZE IN TELEVISED SPORTS PERFORMANCES By SHANNON L. WALSH A Thesis submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Shannon L. Walsh defended on April 6, 2005. ______________________ Carrie Sandahl Professor Directing Thesis ______________________ Mary Karen Dahl Committee Member ______________________ Laura Edmondson Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my husband and loving family. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would most especially like to acknowledge Carrie Sandahl for her feedback on this project over the last two years. You gave me invaluable guidance and advice as I constructed this thesis. I could not have asked for a better advisor or friend. I would also like to acknowledge Debby Thompson. I wouldn’t be where I am without you. Thank you for helping me discover my love for theatre studies. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................ -

News Release

News Release Sprint Nextel Corporation 2001 Edmund Halley Drive Reston, Va. 20191 Media Contact: Mary Nell Westbrook, Sprint, 913-794-3605 [email protected] Brian McCarthy, National Football League, 212-450-2000 [email protected] Sprint and National Football League Ink First-of-Its-Kind, Exclusive Wireless Content and Sponsorship Deal – Delivering the Ultimate Fan Experience Sprint and the NFL will connect to fans through exclusive game highlights, original programming and significant sponsorship of key NFL events as part of an innovative five- year agreement OVERLAND PARK, Kan., and RESTON, Va. ― August 15, 2005 ― Sprint [NYSE: S] and the National Football League (NFL) today announced the completion of a groundbreaking deal that secures Sprint as the official wireless telecommunications service sponsor of the NFL, marking an historic arrangement that reaches beyond marquee branding and delivers first-ever, exclusive NFL content and original programming. “No other sports marketing arrangement comes close to the fan benefits that we’ve achieved with the NFL. It represents a clear departure from the standard sports sponsorship, and delivers exclusively into the hands of Sprint customers and fans an entirely new and interactive experience,” said Tom Murphy, vice president of sponsorships at Sprint. “Beginning this NFL season, innovation takes on new meaning for fans who will be connected to the NFL in a way that’s uniquely their own.” Sprint and Nextel have a history of maximizing sponsorship relationships and the NFL allows an unparalleled content platform to leverage. Shortly after the kickoff of the 2005 NFL season, Sprint will deliver exclusive and original NFL content to mobile phones in new and compelling formats. -

Professional Athletes Playing Video Games - the Next Prohibited Other Activity

Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 3 2008 Professional Athletes Playing Video Games - The Next Prohibited Other Activity Jonathan M. Etkowicz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan M. Etkowicz, Professional Athletes Playing Video Games - The Next Prohibited Other Activity, 15 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 65 (2008). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol15/iss1/3 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Etkowicz: Professional Athletes Playing Video Games - The Next Prohibited O Comments PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES PLAYING VIDEO GAMES - THE NEXT PROHIBITED "OTHER ACTIVITY?" I. INTRODUCTION Statistically, Detroit Tigers pitcher Joel Zumaya ("Zumaya") had an excellent 2006 baseball season, his first in Major League Baseball ("MLB").i Unfortunately, during the 2006 American League Championship Series ("ALCS"), Zumaya was unable to pitch after suffering forearm and wrist inflammation in his pitching arm. 2 The video game Guitar Hero - not his pitching motion - caused the injury.3 Zumaya stopped playing the game and his pitching arm recovered in time for him to pitch in the 2006 World 4 Series against the St. Louis Cardinals. 1. See Joel Zumaya Player Page, http://sportsline.com/mlb/players/player page/580535 (last visited Nov. 15, 2007) (providing key statistics for Zumaya's 2006 season, including eighty-three and one-third innings pitched, six win-three loss record with one save, and ninety-seven strikeouts to forty-two walks). -

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Tuesday, Aug

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2005 Nebraska vs. Maine Nebraska Media Relations–(402) 472-2263 Huskers.com Game 1 8Huskers-Black Bears Briefl y Date: Saturday, Sept. 3, 2005 Time: 6:10 p.m. Site: Lincoln, Neb. Stadium: Memorial Stadium Field: Tom Osborne Field Surface: FieldTurf (2005) vs. Capacity: 73,918 (269th Consecutive Sellout) Nebraska Radio: (Jim Rose–Play-by-Play; Adrian Fiala–Analyst; Randy Lee–Booth; Matt Davison–Sideline) 55-station Pinnacle Sports Network TV: FSN PPV (Greg Sharpe–Play-by-Play; Jayice Pearson-Color; Kent Pavelka-Sideline) Nebraska Maine Internet: Live Radio on Huskers.com Satellite Radio: Sirius Satellite Radio, Channel 134 (0-0) (0-0) Special Events: Hall of Fame Recognition, Brook Berringer Scholarship Presentation This Week in Husker Football Huskers Set for Season Opener Against Maine Tuesday, Aug. 30 Nebraska kicks off the 116th season in school history on Saturday night when the Huskers take on the Maine Weekly Press Conference Black Bears in a 6:10 p.m. contest in Lincoln. The game will be played before the 269th consecutive sellout at 11 a.m. ........................................................................ Lunch Memorial Stadium and will be televised on a pay-per-view basis by FSN. The matchup with Maine begins the Huskers’ second season under the direction of Head Coach Bill Callahan. The 11:30 a.m-Noon .......................................... Player Interviews 2005 Huskers return 12 starters, including six on offense, fi ve on the defensive side of the football and one specialist. Noon.............................................. Head Coach Bill Callahan Saturday night’s game will also be the debut of several talented Husker newcomers who formed a recruiting class 12:20-1:15 p.m.......................................... -

Joe Vitt, Sma '74Pg

JOE VITT, SMA ‘74PG Joe Vitt is the assistant head coach and linebackers coach of the New Orleans Saints. He was the interim head coach for the New Orleans Saints during the 2012 season. Early life Vitt was born August 23, 1954, and was raised in Blackwood, NJ, where he graduated from Highland Regional High School in 1973. Joe spent the 1973-74 school year as a post graduate on the varsity football team of Staunton Military Academy in Virginia. At Towson State University he was a three-year letterman (1974, 1975 and 1977) as a linebacker despite being an undersized 5'10" and smallish 190 pounds. NFL coaching career He entered the National Football League (NFL) as the strength/quality control coach for the Baltimore Colts from 1979 through 1981. Vitt was the Seattle Seahawks' strength coach when Chuck Knox came to be head coach in 1983. He quickly promoted Vitt to defensive backs coach. Vitt moved with Knox to the Los Angeles Rams, where Vitt worked, along with Mike Martz, on his staff from 1992 to1994. Vitt has also been an assistant coach for the Philadelphia Eagles and Green Bay Packers. He served under former St. Louis Rams coach Dick Vermeil for the Kansas City Chiefs for three years until Martz brought him to St. Louis as the assistant head coach and linebackers coach. It marked Vitt's eighth time in the National Football League, and the second with that franchise. During the 2005 NFL season, Vitt served as the interim Head Coach of the Rams while Martz was out due to a bacterial heart infection. -

29 This Is San Antonio

OADRUNNERS OOTBALL UIDE 2011 R INAUGURAL S EAFSON G 2011 UTSA Football Schedule September 3 October 8 Northeastern State South Alabama 1 p.m. 1 p.m. Alamodome Alamodome San Antonio, Texas San Antonio, Texas September 10 October 15 McMurry UC Davis 1 p.m. 4 p.m. (CT) Alamodome Aggie Stadium San Antonio, Texas Davis, Calif. September 17 October 29 Southern Utah Georgia State 7 p.m. (CT) 1 p.m. Eccles Coliseum Alamodome Cedar City, Utah San Antonio, Texas September 24 November 12 Bacone McNeese State 1 p.m. 7 p.m. Alamodome Cowboy Stadium San Antonio, Texas Lake Charles, La. October 1 November 19 Sam Houston State Minot State 6 p.m. 1 p.m. Bowers Stadium Alamodome Huntsville, Texas San Antonio, Texas 2011 UTSA FOOTBALL GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Meet The Roadrunners _________ 56-78 Numerical Roster ___________________________ 56-57 The UTSA Experience _____________3-29 Alphabetical Roster _________________________ 58-59 Student-Athlete Profiles ______________________ 60-77 UTSA Timeline _________________________________ 3 Team Photo ___________________________________ 78 What They’re Saying _________________________4-5 UTSA Football ________________________________6-7 Media Information _____________ 80-88 Media Exposure ______________________________8-9 Quick Facts __________________________________ 80 Park West Athletics Complex _________________ 10-11 2011 Schedule _______________________________ 80 This Is UTSA _______________________________ 12-13 Future Schedules ______________________________ 81 Campus Life _______________________________ -

The Effect of Intelligence on Athletic Performance

The Effect of Intelligence on Athletic Performance David Roy and Christine Yew Introduction Prior to the 2006 NFL Draft, Texas Quarterback Vince Young –coming off a historic Rose Bowl performance – caused a stir of controversy when he scored an abysmal 6 out of 50 on his Wonderlic intelligence test. Both NFL evaluators and NFL media members saw this as a red flag, questioning whether the Texas star would be unable to grasp the intricacies of NFL offenses at its most mentally demanding position. The concern over Young’s intelligence ultimately proved irrelevant to NFL evaluators, for the quarterback was drafted third overall by the Tennessee Titans in the 2006 NFL Draft.1 Young also went on to win 2006-2007 Offensive Rookie of the Year honors. But the Young controversy raises the question: Does academic performance have an impact on athletic performance? In our study, we will specifically look at the National Football League (NFL) for two reasons. First, the NFL has 53 players on each team’s roster, which is greater than any other professional sport, and thus provides us with the greatest potential sample size. Second, the NFL provides the greatest wealth of data measuring intelligence because the Wonderlic intelligence test is given each year at the NFL Pre-Draft Combine to a pool of around 350 potential NFL players – some of whom will make the NFL and some of whom will not make the NFL. Our study will investigate how much value NFL teams assign intelligence in their NFL Draft evaluations for prospective players at each position. -

Gy4dme87ud93qri3t9u7papqy3w

Copyright © 2011 by Tobias J. Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Archetype, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com Crown Archetype with colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moskowitz, Tobias J. (Tobias Jacob), 1971-Scorecasting: The hidden influences behind how sports are played and games are won / Tobias J. Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim. p. cm. 1. Sports--Miscellanea. 2. Sports--Problems, exercises, etc. I. Wertheim, L. Jon. II. Title. GV707.M665 2011 796--dc22 2010035463 eISBN: 978-0-307-59181-4 v3.1 To our wives, to our kids ... and to our parents for driving us between West Lafayette and Bloomington all those years CONTENTS Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Introduction Whistle Swallowing Why fans and leagues want officials to miss calls Go for It Why coaches make decisions that reduce their team's chances of winning How Competitive Are Competitive Sports? Why are the Pittsburgh Steelers so successful and the Pittsburgh Pirates so unsuccessful? Tiger Woods Is Human (and Not for the Reason You Think) How Tiger Woods is just like the rest of us, even when it comes to playing golf Offense Wins Championships, Too Is defense really more important than offense? The Value of a Blocked Shot Why Dwight Howard's 232 blocked shots are worth less than Tim Duncan's 149 Rounding First Why .299 hitters are so much more rare (and maybe more valuable) than .300 hitters Thanks, Mr. -

Notes Afc Standouts Aim for First Pro Bowl

NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE 280 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (212) 450-2000 * FAX (212) 681-7573 WWW.NFLMedia.com Joe Browne, Executive Vice President-Communications Greg Aiello, Vice President-Public Relations AFC NEWS ‘N’ NOTES FOR USE AS DESIRED FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION AFC-N-17 12/6/05 CONTACT: STEVE ALIC (212/450-2066) AFC STANDOUTS AIM FOR FIRST PRO BOWL Heated playoff races and blustery temperatures set the table for an exciting home stretch of the 2005 NFL season. As games are won and legends are born, fans, coaches and players will soon conclude NFL All-Star voting for the 2006 Pro Bowl. Several of this season’s top AFC performers aim to play under the Hawaiian sun for the first time in their careers. Fan voting for the Pro Bowl – which will be held on Sunday, February 12 (ESPN, 6:00 PM ET) – on NFL.com and via Sprint wireless, concludes on December 13. NFL players and coaches will cast their votes on December 19-20, and the team will be announced on Wednesday, December 21 at 4:00 PM (ET) on the 2006 Pro Bowl Selection Show on ESPN. Following are AFC players ranking in the top five in conference statistics who have never been selected to a Pro Bowl: AFC CATEGORY PLAYER TEAM STATISTIC RANKING Passer Rating Carson Palmer Cincinnati 106.6 2 Ben Roethlisberger Pittsburgh 101.5 3 Jake Plummer Denver 91.2 5 Receptions Reggie Wayne Indianapolis 67 2 Deion Branch New England 65 4 Rushing Yards Larry Johnson Kansas City 1,108 3 Reuben Droughns Cleveland 1,029 T5 Willis McGahee Buffalo 1,029 T5 Scrimmage Yards Larry Johnson Kansas City 1,337 T3 LaMont Jordan Oakland 1,337 T3 Reuben Droughns Cleveland 1,329 5 Interceptions Greg Wesley Kansas City 6 3 Cato June Indianapolis 5 T4 Odell Thurman (R) Cincinnati 5 T4 Sacks Derrick Burgess Oakland 11.0 T1 Robert Mathis Indianapolis 10.5 T2 Kyle Vanden Bosch Tennessee 10.5 T2 Aaron Schobel Buffalo 9.0 5 Scoring Lawrence Tynes Kansas City 101 2 Shayne Graham Cincinnati 97 3 Nate Kaeding San Diego 93 4 Punt Returns B.J.