Gy4dme87ud93qri3t9u7papqy3w

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salary Allocation and Risk Preferences in the National Football League

Salary Allocation and Risk Preferences in the National Football League: The Implications of Salary Allocation in Understanding the Preferences of NFL Owners Papa Chakravarthy Presented to the Department of Economics In partial fulfillment of the requirements For a Bachelor of Arts degree with Honors Harvard College Cambridge, Massachusetts March 8th, 2012 Abstract The study of risk preferences in the allocation of the National Football League’s salary cap has not seen much academic research. Previous analysis shows that the salary cap improves parity across the NFL and may be partially responsible for the growth of the United States’ most popular sports league. Allocating salary to players, however, can reveal a great deal of information regarding the utility function of NFL Owners. This paper illustrates, using data on wide receivers in the NFL from 2005 to 2009, variables predicting future performance in the NFL do not predict future salary, meaning Owners value something in addition to future expected performance when allocating salary. The potential to become a star, leadership or popularity may be the characteristic valued by Owners that is not shown by OLS regression. A comparison of NFL Owners to fantasy football owners shows that while the method of risk aversion differs between the two, it is impossible to rule out risk aversion by NFL Owners trying to retain aged players with high salaries. Finally, it is possible that NFL teams may improve team performance while staying within the salary cap by cutting players more frequently and signing shorter contracts, thus eliminating the need to overpay players and fielding a more competitive team. -

Tweet Tweet,Nfl Custom Jerseys Anthony Costanzo, LT,New Nike Nfl Jerseys, Boston College,New Nfl Jerseys, 6?

Tweet Tweet,nfl custom jerseys Anthony Costanzo, LT,new nike nfl jerseys, Boston College,new nfl jerseys, 6?¡¥7 295 Position Ranking: #2 Strengths: Costanzo is always a multi functional its keep effort player who consistently shows? good overall?technique. Has a robust fundamentals,shop nfl jerseys,if you do coached,nfl jerseys cheap,?and uses use of the for more information regarding gain leverage everywhere in the opponents in the run game. Works to understand more about can get inside hand placement it plays allowing you to have consistent knee bend, playing balanced it disciplined. Ideal height it arm length for the position. He?will fully stretch arms at the snap it walk oppenent with heavy hands. Puts she is in?proper position for more information on handle outside a fast boat rush; in line with the initial hit out partying everywhere over the release for additional details on be capable of geting fine detail all around the his pass protection. Shows a good amount of quickness for more information regarding consistently get to understand more about the?second extent it neutralize linebackers it safeties. Can pluck it trap and various other to learn more about going around running lanes within the with above-adequate quickness. Has a good amount of to toe quickness to explore re-direct all around the double moves on the pass protection. Tough. Plays for more information regarding going to be the whistle. Good lateral quickness to learn more about angle cut off Consistently plays exceeding his pads. Needs Improvement: Athleticism may be the one of the more above-adequate. -

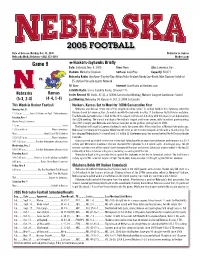

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Sept

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Sept. 12, 2005 Nebraska vs. Pittsburgh Nebraska Media Relations–(402) 472-2263 Huskers.com Game 3 8Huskers-Panthers Briefl y Date: Saturday, Sept. 17, 2005 Time: 2:36 p.m. Site: Lincoln, Neb. Stadium: Memorial Stadium Field: Tom Osborne Field Surface: FieldTurf (2005) vs. Capacity: 73,918 (271st Consecutive Sellout) Nebraska Radio: (Jim Rose–Play-by-Play; Adrian Fiala–Analyst; Randy Lee–Booth; Matt Davison–Sideline) 55-station Pinnacle Sports Network Nebraska Pittsburgh TV: ABC Regional (Brent Musburger-Play-by-Play; Gary Danielson-Color; Jack Arute-Sidelines) (2-0) (0-2) Internet: Live Radio on Huskers.com Satellite Radio: Sirius Satellite Radio, Channel 141 Special Events: Red Cross Appreciation Day This Week in Husker Football Nebraska Looks to Continue Season-Opening Momentum vs. Pitt Monday, Sept. 12 Fresh off two dominant defensive efforts, Nebraska will look to complete non-conference play unbeaten this Saturday when the Huskers play host to defending Big East Conference champion Pittsburgh at Memorial Stadium. 11:50 a.m. ............Coach Callahan on Big 12 Teleconference The game will kickoff at 2:36 p.m. and will be televised to a regional audience by ABC, with Brent Musburger, Gary Tuesday, Sept. 13 Danielson and Jack Arute on the call. Weekly Press Conference Nebraska is off to a 2-0 start thanks in large part to a tenacious Blackshirt defense. After recording school 11 a.m. ........................................................................ Lunch records for sacks and tackles for loss in the opener against Maine, the Husker defense continued its assault on the 11:30 a.m-Noon ......................................... -

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings November 21, 2012

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings November 21, 2012 CINCINNATI ENQUIRER Pitching is pricey, transactions By John Fay | 11/20/2012 12:17 PM ET Want to know why the Reds would be wise to lock up Homer Bailey and Mat Latos long-term? The Kansas City Royals agreed to a three-year deal with Jeremy Guthrie that pays him $5 million on 2013, $11 million in 2014 and $9 million in 2015. He went 8-12 with a 4.76 ERA and 1.41 WHIP. Bailey went 13-10 with a 3.68 ERA and a 1.24 WHIP. Latos went 14-4 with a 2.48 ERA and a 1.16 WHIP. It’s a bit apples and oranges: Guthrie is a free agent; Bailey is arbitration-eligible for the second time, Latos for the first. But the point is starting pitching — even mediocre starting pitching — is expensive. SIX ADDED: The Reds added right-handers Carlos Contreras, Daniel Corcino, Curtis Partch and Josh Ravin, left-hander Ismael Guillon and outfielder Yorman Rodriguez to the roster in order to protect them from the Rule 5 draft. Report: Former Red Frank Pastore badly hurt in motorcycle wreck By dclark | 11/20/2012 7:55 PM ET The Inland Valley Daily Bulletin is reporting that former Cincinnati Reds pitcher Frank Pastore, a Christian radio personality in California, was badly injured Monday night after being thrown from his motorcycle onto the highway near Duarte, Calif. From dailybulletin.com’s Juliette Funes: A 55-year-old motorcyclist from Upland was taken to a trauma center when his motorcycle was hit by a car on the 210 Freeway Monday night. -

Campus Houses Robbed Physicist Analyzes Ice Skating Buddhist Monk

THE INDEPENDENT TO UNCOVER NEWSPAPER SERVING THE TRUTH NOTRE DAME AND AND REPORT SAINT Mary’s IT ACCURATELY VOLUME 47, ISSUE 56 | THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 2013 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM Students address sexual violence Off- Town hall meeting examines survey results, barriers to sexual assault reporting campus By MEG HANDELMAN alert emails and to think sex- News Writer ual violence does not occur at Notre Dame, but the right houses Student government host- thing to do is almost never ed a town hall discussion on easy, Daegele said. sexual violence Wednesday to “Silence: it surrounds every open up the on-campus dis- situation of sexual violence,” robbed cussion and instigate activism she said. “It keeps survivors in students. from telling their stories. It Observer Staff Report Monica Daegele, student makes us pretend that nothing government’s gender issues is wrong. It propagates sexual An email sent Wednesday director, said Notre Dame violence as it alienates those from Notre Dame’s Off Campus students dedicate themselves who have experienced it. Council notified students of to various causes to make the “It is the invisible force field a burglary and attempted world a better place, but they that smothers the sexual vio- burglary that took place last have failed to connect this ef- lence movement.” weekend. fort to sexual assault. Student body president A burglary to a student resi- “When we do discuss sexual Nancy Joyce shared statis- dence took place Sunday be- violence or actively work to put tics from a survey given to tween 12 a.m. and 9 a.m. on an end to it, it feels as though Notre Dame students in 2012. -

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Oct

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Oct. 31, 2005 Nebraska vs. Kansas Nebraska Media Relations–(402) 472-2263 Huskers.com Game 9 8Huskers-Jayhawks Briefl y Date: Saturday, Nov. 5, 2005 Time: Noon Site: Lawrence, Kan. Stadium: Memorial Stadium Surface: AstroPlay Capacity: 50,071 Nebraska Radio: (Jim Rose–Play-by-Play; Adrian Fiala–Analyst; Randy Lee–Booth; Matt Davison–Sideline) vs. 55-station Pinnacle Sports Network TV: None Internet: Live Radio on Huskers.com Satellite Radio: Sirius Satellite Radio, Channel 123 Nebraska Kansas Series Record: NU leads, 87-21-3 (100th Consecutive Meeting, Nation’s Longest Continuous Series) (5-3, 2-3) (4-4, 1-4) Last Meeting: Nebraska 14, Kansas 8, Oct. 2, 2004, in Lincoln This Week in Husker Football Huskers, Kansas Set to Meet for 100th Consecutive Year Monday, Oct. 31 Nebraska and Kansas renew one of the longest-standing series’ in college football this Saturday, when the 11:50 a.m. ............Coach Callahan on Big 12 Teleconference Huskers travel to Lawrence, Kan., to match up with the Jayhawks in a Big 12 Conference North Division matchup. The Nebraska-Jayhawk series is tied for the third-longest in Division I-A history, with this week’s matchup marking Tuesday, Nov. 1 the 112th meeting. The annual matchup is the nation’s longest continuous series, with Saturday’s game marking Weekly Press Conference the 100th straight year Nebraska and Kansas have met on the gridiron, dating back to 1906. 11 a.m. ........................................................................ Lunch The Huskers will travel to Lawrence looking to end a two-game slide. After a road loss at Missouri two weeks ago, 11:30 a.m-Noon ......................................... -

Download Flying with the Eagles, Mary Mitchell Douglas, Wildot Press

Flying with the Eagles, Mary Mitchell Douglas, Wildot Press, 1994, 0964376407, 9780964376403, . DOWNLOAD HERE , , , , . Kansas vs Duke | 2013 ACC Basketball Highlights Dashcam: Trooper and Suspect Fall from Overpass During Chase Kim Kardashian Posts Baby Pics Hoop Falls, Breaks on Harlem Globetrotter After Dunk Nicole Scherzinger Goes Commando Golf Pros Hit The Green From 22 Story Tee Most expensive piece of art ever auctioned off in Manhattan Kate Hudson Sparkles in a Sexy Swimsuit Miranda Kerr Flaunts Her Flat Abs TSA Officer Remembered In Public Ceremony WATCH: Marines Show Dance Skills at Marine Corps Ball Jennifer Lawrence Goes Backless Rare Sequential Date 11/12/13 Becomes Popular Day For Weddings Shocking DWTS Elimination Caught on Camera: Crosswalk Hit & Run US Senator's Son Killed in Plane Crash Miley Cyrus is a Nude Alien in Future's 'Real and True' Music Video Christie's to auction the world's largest orange diamond Lady Gaga Debuts the World's First Flying Dress at ARTPOP Release Party Robach Reveals Cancer Diagnosis Donovan Jamal McNabb (born November 25, 1976) is a retired American football quarterback who played in the National Football League (NFL) for thirteen seasons. Before his NFL career, he played football and basketball for Syracuse University. The Philadelphia Eagles selected him with the second overall pick in the 1999 NFL Draft. He is currently an analyst on NFL Network and Fox Sports. Donovan McNabb was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. He attended Mount Carmel High School where, as a sophomore, he was a teammate of future NFL players Simeon Rice and Matt Cushing. -

Wrigley Field

Jordan, J. The Origination of Baseball and Its Stadiums 1 Running header: THE ORIGINATION OF BASEBALL AND ITS STADIUMS The Origination of Baseball and Its Stadiums: Wrigley Field Justin A. Jordan North Carolina State University Landscape Architecture 444 Prof. Fernando Magallanes December 7, 2012 Jordan, J. The Origination of Baseball and Its Stadiums 2 Abstract Baseball is America’s Pastime and is home for some of the most influential people and places in the USA. Since the origination of baseball itself, fields and ball parks have had emotional effects on Americans beginning long before the creation of the USA. In this paper, one will find the background of the sport and how it became as well as the first ball parks and their effects on people in the USA leading up to the discussion about Wrigley Field in Chicago, Illinois. Jordan, J. The Origination of Baseball and Its Stadiums 3 Baseball. This one word could represent the American pastime and culture. Many believe it to be as old as dirt. Peter Morris in his book, Level Playing Fields, explains “Baseball is sometimes said to be older than dirt. It is one of those metaphors that sounds silly on its face but that still resonates because it hints at a deeper truth. In this case, the deeper truth is that neither baseball nor dirt is quite complete without the other” (Morris, 2007). Morris practically says that baseball cannot thrive without proper fields to play on or parks to play in. Before describing early playing fields and stadiums in baseball, one must know where the sport and idea originated from in the first place. -

2010 Topps Baseball Set Checklist

2010 TOPPS BASEBALL SET CHECKLIST 1 Prince Fielder 2 Buster Posey RC 3 Derrek Lee 4 Hanley Ramirez / Pablo Sandoval / Albert Pujols LL 5 Texas Rangers TC 6 Chicago White Sox FH 7 Mickey Mantle 8 Joe Mauer / Ichiro / Derek Jeter LL 9 Tim Lincecum NL CY 10 Clayton Kershaw 11 Orlando Cabrera 12 Doug Davis 13 Melvin Mora 14 Ted Lilly 15 Bobby Abreu 16 Johnny Cueto 17 Dexter Fowler 18 Tim Stauffer 19 Felipe Lopez 20 Tommy Hanson 21 Cristian Guzman 22 Anthony Swarzak 23 Shane Victorino 24 John Maine 25 Adam Jones 26 Zach Duke 27 Lance Berkman / Mike Hampton CC 28 Jonathan Sanchez 29 Aubrey Huff 30 Victor Martinez 31 Jason Grilli 32 Cincinnati Reds TC 33 Adam Moore RC 34 Michael Dunn RC 35 Rick Porcello 36 Tobi Stoner RC 37 Garret Anderson 38 Houston Astros TC 39 Jeff Baker 40 Josh Johnson 41 Los Angeles Dodgers FH 42 Prince Fielder / Ryan Howard / Albert Pujols LL Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Marco Scutaro 44 Howie Kendrick 45 David Hernandez 46 Chad Tracy 47 Brad Penny 48 Joey Votto 49 Jorge De La Rosa 50 Zack Greinke 51 Eric Young Jr 52 Billy Butler 53 Craig Counsell 54 John Lackey 55 Manny Ramirez 56 Andy Pettitte 57 CC Sabathia 58 Kyle Blanks 59 Kevin Gregg 60 David Wright 61 Skip Schumaker 62 Kevin Millwood 63 Josh Bard 64 Drew Stubbs RC 65 Nick Swisher 66 Kyle Phillips RC 67 Matt LaPorta 68 Brandon Inge 69 Kansas City Royals TC 70 Cole Hamels 71 Mike Hampton 72 Milwaukee Brewers FH 73 Adam Wainwright / Chris Carpenter / Jorge De La Ro LL 74 Casey Blake 75 Adrian Gonzalez 76 Joe Saunders 77 Kenshin Kawakami 78 Cesar Izturis 79 Francisco Cordero 80 Tim Lincecum 81 Ryan Theroit 82 Jason Marquis 83 Mark Teahen 84 Nate Robertson 85 Ken Griffey, Jr. -

Baseball Broadcasting in the Digital Age

Baseball broadcasting in the digital age: The role of narrative storytelling Steven Henneberry CAPSTONE PROJECT University of Minnesota School of Journalism and Mass Communication June 29, 2016 Table of Contents About the Author………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction/Background…………………………………………………………………… 6 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………… 10 Primary Research Studies Study I: Content Analysis…………………………………………………………… 17 Study II: Broadcaster Interviews………………………………………………… 31 Study III: Baseball Fan Interviews……………………………………………… 48 Conclusion/Recommendations…………………………………………………………… 60 References………………………………………………………………………………………….. 65 Appendix (A) Study I: Broadcaster Biographies Vin Scully……………………………………………………………………… 69 Pat Hughes…………………………………………………………………… 72 Ron Coomer…………………………………………………………………… 72 Cory Provus…………………………………………………………………… 73 Dan Gladden…………………………………………………………………… 73 Jon Miller………………………………………………………………………… 74 (B) Study II: Broadcaster Interview Transcripts Pat Hughes…………………………………………………………………… 75 Cory Provus…………………………………………………………………… 82 Jon Miller……………………………………………………………………… 90 (C) Study III: Baseball Fan Interview Transcripts Donna McAllister……………………………………………………………… 108 Rick Moore……………………………………………………………………… 113 Rowdy Pyle……………………………………………………………………… 120 Sam Kraemer…………………………………………………………………… 121 Henneberry 2 About the Author The sound of Chicago Cubs baseball has been a near constant part of Steve Henneberry’s life. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

BB Competition Rules V2

BLOOD BOWL BLOOD BOWL COMPETITION RULES This rules pack contains a set of alternative game rules that have been developed in order to maintain game balance in leagues that last for long periods of time (e.g. for months or years rather than weeks), and for use in tournaments where very precise play balance and exact wording of the rules are important. They have been heavily tested by Blood Bowl coaches around the world, to ensure the best long-term balance and minimum of confusion. However, by necessity this makes the competition rules longer and more complex than the standard rules, and because of this their use is entirely optional. League commissioners and tournament organisers should therefore feel free to use either the competition rules or the standard rules included with the Blood Bowl game, whichever they consider to be the most appropriate for the league or tournament they plan to run. Note that the Competition Rules pack only includes the information and rules that you will need during play. All descriptions of game components, the history of Blood Bowl, and all illustrations and ‘Did You Knows’ have been removed, both in order to save repeating information already in the Blood Bowl Rulebook, and to save time and money when printing the document out. We recommend printing two pages to a sheet to save further paper. Also note that the original page numbering has been preserved as much as possible, to ensure that page references in the text remain correct, and this sometimes means that the page numbers ‘jump forward’ or that pages have a certain amount of empty space.