The Effect of Intelligence on Athletic Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salary Allocation and Risk Preferences in the National Football League

Salary Allocation and Risk Preferences in the National Football League: The Implications of Salary Allocation in Understanding the Preferences of NFL Owners Papa Chakravarthy Presented to the Department of Economics In partial fulfillment of the requirements For a Bachelor of Arts degree with Honors Harvard College Cambridge, Massachusetts March 8th, 2012 Abstract The study of risk preferences in the allocation of the National Football League’s salary cap has not seen much academic research. Previous analysis shows that the salary cap improves parity across the NFL and may be partially responsible for the growth of the United States’ most popular sports league. Allocating salary to players, however, can reveal a great deal of information regarding the utility function of NFL Owners. This paper illustrates, using data on wide receivers in the NFL from 2005 to 2009, variables predicting future performance in the NFL do not predict future salary, meaning Owners value something in addition to future expected performance when allocating salary. The potential to become a star, leadership or popularity may be the characteristic valued by Owners that is not shown by OLS regression. A comparison of NFL Owners to fantasy football owners shows that while the method of risk aversion differs between the two, it is impossible to rule out risk aversion by NFL Owners trying to retain aged players with high salaries. Finally, it is possible that NFL teams may improve team performance while staying within the salary cap by cutting players more frequently and signing shorter contracts, thus eliminating the need to overpay players and fielding a more competitive team. -

Texas Coach Mack Brown

July 24, 2012 An Interview With: Wood and wood transfers, so it was all over the place. TEXAS What we have done now, we have two older guys that have been through a year with COACH MACK BROWN Bryan Harsin and Major Applewhite offense. They both won significant games, one against -- Case against A&M in College Station at the end of the year, David Ash in the Bowl game against Cal. THE MODERATOR: We're now joined by So we're coming in at a much better place Mack Brown from Texas. Coach, welcome and this year than we were last year. your opening comments. They left spring practice even. In talking to COACH BROWN: Well, I'm sitting in a red the guys last night, they've had a very competitive chair; I don't do that very often from the Big 12. summer, and both of them are in the mix and we We have three players here today: Mason should have a great battle at that position in Walters, who is an offensive lineman that's about preseason. If you sit there and you say we'd rather 6'6", 325; we have Carrington Byndom, who is an have Vince Young, we'd rather have Colt McCoy, outstanding defensive back for us last year that there's no question those are two of the best made the huge interception in the A&M game for a quarterbacks to ever play college football. You'd touchdown that kind of turned the game; and we like to have that luxury. -

Game Summaries:IMG.Qxd

Sunday, September 12, 2010 Green Bay Packers 27 Lincoln Financial Field Philadelphia Eagles 20 Clad in their Kelly green uniforms in honor of the 1960 NFL cham- 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Pts pions, the Philadelphia Eagles made a valiant comeback attempt Green Bay 013140-27 but fell just short in the final minutes of the season opener vs. Green Philadelphia 30710-20 Bay. Philadelphia fell behind 13-3 at half and 27-10 in the 4th quar- ter and lost four key players along the way: starting QB Kevin Kolb Phila - D.Akers, 45 FG (8-26, 4:00) (concussion), MLB Stewart Bradley (concussion), FB Leonard GB - M.Crosby, 49 FG (10-43, 5:31) Weaver (ACL), and C Jamaal Jackson (triceps). But behind the arm GB - D. Driver, 6 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (11-76, 5:33) and legs of back-up signal caller Michael Vick, the Eagles rallied to GB - M.Crosby, 56 FG (7-39, 0:41) make the score 27-20 late in the 4th quarter. In fact, they took over GB - J.Kuhn, 3 run (Crosby) (10-62, 4:53) possession at their own 24-yard-line with 4:13 to play and drove to Phila - L.McCoy, 12 run (Akers) (9-60, 4:12) the GB42 before Vick was tackled short of a first down on a 4th-and- GB - G.Jennings, 32 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (4-51, 2:28) 1 rushing attempt to seal the Packers victory. After the Eagles took Phila - J.Maclin, 17 pass from Vick (Akers) (9-79, 3:39) a 3-0 lead after an interception by Joselio Hanson, Green Bay took Phila - D.Akers, 24 FG (9-45, 3:31) control over the remainder of the first half. -

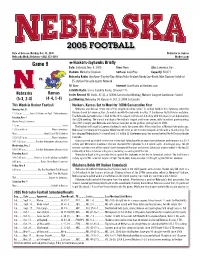

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Sept

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Sept. 12, 2005 Nebraska vs. Pittsburgh Nebraska Media Relations–(402) 472-2263 Huskers.com Game 3 8Huskers-Panthers Briefl y Date: Saturday, Sept. 17, 2005 Time: 2:36 p.m. Site: Lincoln, Neb. Stadium: Memorial Stadium Field: Tom Osborne Field Surface: FieldTurf (2005) vs. Capacity: 73,918 (271st Consecutive Sellout) Nebraska Radio: (Jim Rose–Play-by-Play; Adrian Fiala–Analyst; Randy Lee–Booth; Matt Davison–Sideline) 55-station Pinnacle Sports Network Nebraska Pittsburgh TV: ABC Regional (Brent Musburger-Play-by-Play; Gary Danielson-Color; Jack Arute-Sidelines) (2-0) (0-2) Internet: Live Radio on Huskers.com Satellite Radio: Sirius Satellite Radio, Channel 141 Special Events: Red Cross Appreciation Day This Week in Husker Football Nebraska Looks to Continue Season-Opening Momentum vs. Pitt Monday, Sept. 12 Fresh off two dominant defensive efforts, Nebraska will look to complete non-conference play unbeaten this Saturday when the Huskers play host to defending Big East Conference champion Pittsburgh at Memorial Stadium. 11:50 a.m. ............Coach Callahan on Big 12 Teleconference The game will kickoff at 2:36 p.m. and will be televised to a regional audience by ABC, with Brent Musburger, Gary Tuesday, Sept. 13 Danielson and Jack Arute on the call. Weekly Press Conference Nebraska is off to a 2-0 start thanks in large part to a tenacious Blackshirt defense. After recording school 11 a.m. ........................................................................ Lunch records for sacks and tackles for loss in the opener against Maine, the Husker defense continued its assault on the 11:30 a.m-Noon ......................................... -

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Oct

2005 FOOTBALL Date of Release: Monday, Oct. 31, 2005 Nebraska vs. Kansas Nebraska Media Relations–(402) 472-2263 Huskers.com Game 9 8Huskers-Jayhawks Briefl y Date: Saturday, Nov. 5, 2005 Time: Noon Site: Lawrence, Kan. Stadium: Memorial Stadium Surface: AstroPlay Capacity: 50,071 Nebraska Radio: (Jim Rose–Play-by-Play; Adrian Fiala–Analyst; Randy Lee–Booth; Matt Davison–Sideline) vs. 55-station Pinnacle Sports Network TV: None Internet: Live Radio on Huskers.com Satellite Radio: Sirius Satellite Radio, Channel 123 Nebraska Kansas Series Record: NU leads, 87-21-3 (100th Consecutive Meeting, Nation’s Longest Continuous Series) (5-3, 2-3) (4-4, 1-4) Last Meeting: Nebraska 14, Kansas 8, Oct. 2, 2004, in Lincoln This Week in Husker Football Huskers, Kansas Set to Meet for 100th Consecutive Year Monday, Oct. 31 Nebraska and Kansas renew one of the longest-standing series’ in college football this Saturday, when the 11:50 a.m. ............Coach Callahan on Big 12 Teleconference Huskers travel to Lawrence, Kan., to match up with the Jayhawks in a Big 12 Conference North Division matchup. The Nebraska-Jayhawk series is tied for the third-longest in Division I-A history, with this week’s matchup marking Tuesday, Nov. 1 the 112th meeting. The annual matchup is the nation’s longest continuous series, with Saturday’s game marking Weekly Press Conference the 100th straight year Nebraska and Kansas have met on the gridiron, dating back to 1906. 11 a.m. ........................................................................ Lunch The Huskers will travel to Lawrence looking to end a two-game slide. After a road loss at Missouri two weeks ago, 11:30 a.m-Noon ......................................... -

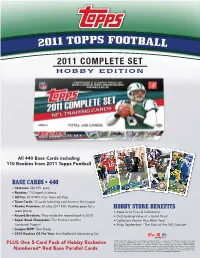

2011 Topps Football 2011 Complete Set Hobby Edition

2011 TOPPS FOOTBALL 2011 COMPLETE SET HOBBY EDITION All 440 Base Cards including 110 Rookies from 2011 Topps Football BASE CARDS • 440 • Veterans: 262 NFL pros. • Rookies: 110 hopeful talents. • All-Pro: 2010 NFL First Team All-Pros. • Team Cards: 32 cards featuring each team in the league. • Rookie Premiere: 30 elite 2011 NFL Rookies pose for a HOBBY STORE BENEFITS team photo. • Appeals to Fans & Collectors! • Record Breakers: They made the record book in 2010. • Outstanding Value at a Great Price! • Super Bowl Champions: The Packers and the • Collectors Return Year After Year! Lombardi Trophy! • Ships September - The Start of the NFL Season! • League MVP: Tom Brady • 2010 Rookies Of The Year: Sam Bradford & Ndamukong Suh ® TM & © 2011 The Topps Company, Inc. Topps and Topps Football are trademarks of The Topps Company, Inc. All rights reserved. © 2011 NFL Properties, LLC. Team Names/Logos/Indicia are trademarks of the teams indicated. All other PLUS One 5-Card Pack of Hobby Exclusive NFL-related trademarks are trademarks of the National Football League. Officially Licensed Product of NFL PLAYERS | NFLPLAYERS.COM. Please note that you must obtain the approval of the National Football League Properties in promotional materials that incorporate any marks, designs, logos, etc. of the National Football League or any of its teams, unless the Numbered* Red Base Parallel Cards material is merely an exact depiction of the authorized product you purchase from us. Topps does not, in any manner, make any representations as to whether its cards will attain any future value. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PLUS ONE 5-CARD PACK OF HOBBY EXCLUSIVE NUMBERED RED BASE PARALLEL CARDS 2011 COMPLETE SET CHECKLIST 1 Aaron Rodgers 69 Tyron Smith 137 Team Card 205 John Kuhn 273 LeGarrette Blount 341 Braylon Edwards 409 D.J. -

In the News Week of August 19 2019

HIGH S CHOOL FOOTBALL PRES EAS ON TOP 10 In Central Texas, August means scorching days and heated preseason debates about the area's top high school football teams. Leading up to the season's klckoff Aug. 29, we unveil our Top JO, as selected by our high school reporting staff. No. 10 Regents Regents quaterback Wilson Long, left, has led the Knights to back•to•batk title games in his two years as a starter. The senior returns after amassing 5,200 yards passing, 2.080 yards rushing and TT total touchdowns In two seasons. [STEPHE'N SPILLMAN/ FOR AMERICAN-SIATESMANJ Coach: Beck Brydon (185-60. FEEDING THE BEAST OUR TAKE 20th season) 2018: ll·2, TAPPS Division II There will be plenty of new Why has Regents been able to state finalist faces in front of QB Long, but sustain its success for so long? Hello: QB Wilson Long, OU one familiar face remains to Rick cantu: Itstarts with the DL Charlie Stone. LB Thomas anchor the offensive line. Senior coach. Beck Brydon established Scully Charlie Stone returns for his a culture many years ago and his Goodbye: OL Noah Bryce, WR/ final year. Brydon touts Stone's players have bought in. A37-4 DB Will Tyler Brydon, RB/OB tenacity, calling the 270-pounder record over the last three years as Zach Smith apancake machine. phenomenal. Returning starters: 5 offense, 7 Thomas Jones: Iagree. Brydon defense DUALTHREAT BACK has been at the school since 1997 2018 stats: Averaged 34.8 ppg, and he's made Regents an attrac allowed 14.4 ppg. -

Essential Dynasty Cheat Sheet

The Essential Dynasty League Rankings Quarterbacks Running Backs (cont.) 1. Aaron Rodgers, GB 51. Jason Campbell, CHI 26. David Wilson, NYG (R) 76. Jason Snelling, ATL 2. Cam Newton, CAR 52. Chase Daniel, NO 27. Roy Helu, WAS 77. Marcel Reece, OAK 3. Drew Brees, NO 53. David Garrard, MIA 28. Kendall Hunter, SF 78. Kahlil Bell, CHI 4. Matthew Stafford, DET 53. Tyrod Taylor, BAL 29. Stevan Ridley, NE 79. Tim Hightower, WAS 5. Tom Brady, NE 54. Shaun Hill, DET 30. Isaiah Pead, STL (R) 80. Brandon Jacobs, SF 6. Andrew Luck, IND 55. Terrelle Pryor, OAK 31. Ronnie Hillman, DEN (R) 81. Danny Woodhead, NE 7. Matt Ryan, ATL 56. Stephen McGee, DAL 32. DeAngelo Williams, CAR 82. Dion Lewis, PHI 8. Eli Manning, NYG 57. BJ Coleman, GB (R) 33. Michael Turner, ATL 83. Dan Herron, CIN (R) 9. Robert Griffin III, WAS (R) 58. Colt McCoy, CLE 34. James Starks, GB 84. Cedric Benson, FA 10. Philip Rivers, SD 59. Vince Young, BUF 35. Fred Jackson, BUF 85. Vick Ballard, IND (R) 11. Tony Romo, DAL 60. Rex Grossman, WAS 36. Michael Bush, CHI 86. Ryan Grant, FA 12. Ben Roethlisberger, PIT 61. Luke McCown, NO 37. Jahvid Best, DET 87. Justin Forsett, HOU 13. Jay Cutler, CHI 62. Ricki Stanzi, KC 38. Donald Brown, IND 88. Joseph Addai, FA 14. Michael Vick, PHI 63. Matt Leinart, OAK 39. Shane Vereen, NE 89. Chris Ogbonnaya, CLE 15. Jake Locker, TEN 64. Jimmy Clausen, CAR 40. Shonn Greene, NYJ 90. Michael Smith, TB (R) 16. Sam Bradford, STL 65. -

2017 National College Football Awards Association Master Calendar

2017 National College Football 9/20/2017 1:58:08 PM Awards Association Master Calendar Award ...................................................Watch List Semifinalists Finalists Winner Banquet/Presentation Bednarik Award .................................July 10 Oct. 30 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Biletnikoff Award ...............................July 18 Nov. 13 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 10, 2018 (Tallahassee, Fla.) Bronko Nagurski Trophy ...................July 13 Nov. 16 Dec. 4 Dec. 4 (Charlotte) Broyles Award .................................... Nov. 21 Nov. 27 Dec. 5 [RCS] Dec. 5 (Little Rock, Ark.) Butkus Award .....................................July 17 Oct. 30 Nov. 20 Dec. 5 Dec. 5 (Winner’s Campus) Davey O’Brien Award ........................July 19 Nov. 7 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 19, 2018 (Fort Worth) Disney Sports Spirit Award .............. Dec. 7 [THDA] Dec. 7 (Atlanta) Doak Walker Award ..........................July 20 Nov. 15 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 16, 2018 (Dallas) Eddie Robinson Award ...................... Dec. 5 Dec. 14 Jan. 6, 2018 (Atlanta) Gene Stallings Award ....................... May 2018 (Dallas) George Munger Award ..................... Nov. 16 Dec. 11 Dec. 27 March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Heisman Trophy .................................. Dec. 4 Dec. 9 [ESPN] Dec. 10 (New York) John Mackey Award .........................July 11 Nov. 14 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [RCS] TBA Lou Groza Award ................................July 12 Nov. 2 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Dec. 4 (West Palm Beach, Fla.) Maxwell Award .................................July 10 Oct. 30 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Outland Trophy ....................................July 13 Nov. 15 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Jan. 10, 2018 (Omaha) Paul Hornung Award .........................July 17 Nov. 9 Dec. 6 TBA (Louisville) Paycom Jim Thorpe Award ..............July 14 Oct. -

17 08 Tradition.Indd

1954 BRUINS-NATIONAL CHAMPIONS BBRUINRUIN FFOOTBALLOOTBALL TTRADITIONRADITION 11954954 BRUINSBRUINS - NATIONALNATIONAL CHAMPIONSCHAMPIONS Fifty-four years ago, UCLA fi elded the fi nest football team in the school’s fi nal 15 minutes to fi nish the season with a perfect 9-0 record. history. The 1954 Bruins compiled a perfect 9-0 record and were voted National UCLA did not play in the Rose Bowl following that magical season because of the & STAFFCOACHES 2008 BRUINS Champions by United Press International at the end of the season. “no-repeat” rule. It was voted No. 1 on the United Press International poll and shared Most of the key players from the 1953 Bruins, who were 8-2, re- the national championship with Ohio State (the Associated Press champ). turned in 1954, led by legendary head coach Henry R. “Red” Sand- The 1954 team set numerous records, including points in a season (367), points ers. During his nine seasons in Westwood, Sanders’ winning per- in a game (72) and touchdowns in a season (55). It led the nation in scoring offense centage was .773 and he won three Pacifi c Coast Conference titles. (40.8 average) and scoring defense (4.4 average). Today, it still ranks No. 1 in school The Bruins opened the 1954 season on Sept. 18 with a 67-0 victory over San Diego history in rushing defense (659 yards), total defense (1,708 yards) and scoring defense Navy at the Coliseum. The point total was the highest in school history at the time. The (40 points) while its 40.8 scoring average ranks second in school history. -

Veteran Player Profiles

VETERAN PLAYER PROFILES Staff/Coaches DENVER BRONCOS MCTELVIN AGIM 95 DEFENSIVE LINEMAN Players 6-3 • 309 • 2ND YR. • ARKANSAS BORN: Sept. 25, 1997, in Texarkana, Texas HIGH SCHOOL: Hope (Ark.) High School Roster Breakdown 2020 Season History/Results Year-by-Year Stats Postseason Records Honors ACQUIRED: Draft #3c (95th overall), 2020 NFL YEAR: 2nd • YEAR WITH BRONCOS: 2nd NFL GAMES PLAYED/STARTED: 10/0 AGIM AT A GLANCE: • A second-year defensive lineman from the University of Arkansas who appeared in 10 games with the Broncos in 2020. • Totaled eight tackles (2 solo) and a pass defensed in his inaugural campaign. • Started 40-of-49 games played at Arkansas, totaling 148 tackles (62 solo), 14.5 sacks (81 yds.), six forced fumbles and two fumble recoveries during his collegiate career. • Appeared in all 12 games during his final campaign with the Razorbacks in 2019, collecting 39 tackles (20 solo) and a collegiate-high five sacks (24 yds.) • Excelled in the classroom, receiving Fall SEC Academic Honor Roll honors for three consec- utive years (2017-19). • Prepped at Hope (Ark.) High School where he was named the Gatorade Arkansas Football Player of the Year and the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette All-Arkansas Preps Defensive Player of the Year as a senior in 2015. • Earned the 2015 Paul Eells Award which is given annually to an Arkansas high school football player who best exhibits perseverance, determination, courage and resolve in the face of adversity. • Selected by the Broncos in the third round (95th overall) of the 2020 NFL Draft. CAREER TRANSACTIONS: Signed by Denver as a draft choice 7/22/20. -

Subverting the Male Gaze in Televised Sports Performances Shannon L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Unsportsman-like Conduct: Subverting the Male Gaze in Televised Sports Performances Shannon L. Walsh Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF THEATRE UNSPORTSMAN-LIKE CONDUCT: SUBVERTING THE MALE GAZE IN TELEVISED SPORTS PERFORMANCES By SHANNON L. WALSH A Thesis submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Shannon L. Walsh defended on April 6, 2005. ______________________ Carrie Sandahl Professor Directing Thesis ______________________ Mary Karen Dahl Committee Member ______________________ Laura Edmondson Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my husband and loving family. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would most especially like to acknowledge Carrie Sandahl for her feedback on this project over the last two years. You gave me invaluable guidance and advice as I constructed this thesis. I could not have asked for a better advisor or friend. I would also like to acknowledge Debby Thompson. I wouldn’t be where I am without you. Thank you for helping me discover my love for theatre studies. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................