Lesson 15: Rotations, Reflections, and Symmetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Order for the Figure to Map Onto Itself, the Line of Reflection Must Go Through the Center Point

3-5 Symmetry State whether the figure appears to have line symmetry. Write yes or no. If so, copy the figure, draw all lines of symmetry, and state their number. 1. SOLUTION: A figure has reflectional symmetry if the figure can be mapped onto itself by a reflection in a line. The figure has reflectional symmetry. In order for the figure to map onto itself, the line of reflection must go through the center point. Two lines of reflection go through the sides of the figure. Two lines of reflection go through the vertices of the figure. Thus, there are four possible lines that go through the center and are lines of reflections. Therefore, the figure has four lines of symmetry. eSolutionsANSWER: Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 yes; 4 2. SOLUTION: A figure has reflectional symmetry if the figure can be mapped onto itself by a reflection in a line. The given figure does not have reflectional symmetry. There is no way to fold or reflect it onto itself. ANSWER: no 3. SOLUTION: A figure has reflectional symmetry if the figure can be mapped onto itself by a reflection in a line. The given figure has reflectional symmetry. The figure has a vertical line of symmetry. It does not have a horizontal line of symmetry. The figure does not have a line of symmetry through the vertices. Thus, the figure has only one line of symmetry. ANSWER: yes; 1 State whether the figure has rotational symmetry. Write yes or no. If so, copy the figure, locate the center of symmetry, and state the order and magnitude of symmetry. -

Enhancing Self-Reflection and Mathematics Achievement of At-Risk Urban Technical College Students

Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, Volume 53, 2011 (1), 108-127 Enhancing self-reflection and mathematics achievement of at-risk urban technical college students Barry J. Zimmerman1, Adam Moylan2, John Hudesman3, Niesha White3, & Bert Flugman3 Abstract A classroom-based intervention study sought to help struggling learners respond to their academic grades in math as sources of self-regulated learning (SRL) rather than as indices of personal limita- tion. Technical college students (N = 496) in developmental (remedial) math or introductory col- lege-level math courses were randomly assigned to receive SRL instruction or conventional in- struction (control) in their respective courses. SRL instruction was hypothesized to improve stu- dents’ math achievement by showing them how to self-reflect (i.e., self-assess and adapt to aca- demic quiz outcomes) more effectively. The results indicated that students receiving self-reflection training outperformed students in the control group on instructor-developed examinations and were better calibrated in their task-specific self-efficacy beliefs before solving problems and in their self- evaluative judgments after solving problems. Self-reflection training also increased students’ pass- rate on a national gateway examination in mathematics by 25% in comparison to that of control students. Key words: self-regulation, self-reflection, math instruction 1 Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Barry Zimmerman, PhD, Graduate Center of the City University of New York and Center for Advanced Study in Education, 365 Fifth Ave- nue, New York, NY 10016, USA; email: [email protected] 2 Now affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine 3 Graduate Center of the City University of New York and Center for Advanced Study in Education Enhancing self-reflection and math achievement 109 Across America, faculty and policy makers at two-year and technical colleges have been deeply troubled by the low academic achievement and high attrition rate of at-risk stu- dents. -

Reflection Invariant and Symmetry Detection

1 Reflection Invariant and Symmetry Detection Erbo Li and Hua Li Abstract—Symmetry detection and discrimination are of fundamental meaning in science, technology, and engineering. This paper introduces reflection invariants and defines the directional moments(DMs) to detect symmetry for shape analysis and object recognition. And it demonstrates that detection of reflection symmetry can be done in a simple way by solving a trigonometric system derived from the DMs, and discrimination of reflection symmetry can be achieved by application of the reflection invariants in 2D and 3D. Rotation symmetry can also be determined based on that. Also, if none of reflection invariants is equal to zero, then there is no symmetry. And the experiments in 2D and 3D show that all the reflection lines or planes can be deterministically found using DMs up to order six. This result can be used to simplify the efforts of symmetry detection in research areas,such as protein structure, model retrieval, reverse engineering, and machine vision etc. Index Terms—symmetry detection, shape analysis, object recognition, directional moment, moment invariant, isometry, congruent, reflection, chirality, rotation F 1 INTRODUCTION Kazhdan et al. [1] developed a continuous measure and dis- The essence of geometric symmetry is self-evident, which cussed the properties of the reflective symmetry descriptor, can be found everywhere in nature and social lives, as which was expanded to 3D by [2] and was augmented in shown in Figure 1. It is true that we are living in a spatial distribution of the objects asymmetry by [3] . For symmetric world. Pursuing the explanation of symmetry symmetry discrimination [4] defined a symmetry distance will provide better understanding to the surrounding world of shapes. -

Molecular Symmetry

Molecular Symmetry Symmetry helps us understand molecular structure, some chemical properties, and characteristics of physical properties (spectroscopy) – used with group theory to predict vibrational spectra for the identification of molecular shape, and as a tool for understanding electronic structure and bonding. Symmetrical : implies the species possesses a number of indistinguishable configurations. 1 Group Theory : mathematical treatment of symmetry. symmetry operation – an operation performed on an object which leaves it in a configuration that is indistinguishable from, and superimposable on, the original configuration. symmetry elements – the points, lines, or planes to which a symmetry operation is carried out. Element Operation Symbol Identity Identity E Symmetry plane Reflection in the plane σ Inversion center Inversion of a point x,y,z to -x,-y,-z i Proper axis Rotation by (360/n)° Cn 1. Rotation by (360/n)° Improper axis S 2. Reflection in plane perpendicular to rotation axis n Proper axes of rotation (C n) Rotation with respect to a line (axis of rotation). •Cn is a rotation of (360/n)°. •C2 = 180° rotation, C 3 = 120° rotation, C 4 = 90° rotation, C 5 = 72° rotation, C 6 = 60° rotation… •Each rotation brings you to an indistinguishable state from the original. However, rotation by 90° about the same axis does not give back the identical molecule. XeF 4 is square planar. Therefore H 2O does NOT possess It has four different C 2 axes. a C 4 symmetry axis. A C 4 axis out of the page is called the principle axis because it has the largest n . By convention, the principle axis is in the z-direction 2 3 Reflection through a planes of symmetry (mirror plane) If reflection of all parts of a molecule through a plane produced an indistinguishable configuration, the symmetry element is called a mirror plane or plane of symmetry . -

History of Mathematics

Georgia Department of Education History of Mathematics K-12 Mathematics Introduction The Georgia Mathematics Curriculum focuses on actively engaging the students in the development of mathematical understanding by using manipulatives and a variety of representations, working independently and cooperatively to solve problems, estimating and computing efficiently, and conducting investigations and recording findings. There is a shift towards applying mathematical concepts and skills in the context of authentic problems and for the student to understand concepts rather than merely follow a sequence of procedures. In mathematics classrooms, students will learn to think critically in a mathematical way with an understanding that there are many different ways to a solution and sometimes more than one right answer in applied mathematics. Mathematics is the economy of information. The central idea of all mathematics is to discover how knowing some things well, via reasoning, permit students to know much else—without having to commit the information to memory as a separate fact. It is the reasoned, logical connections that make mathematics coherent. The implementation of the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Mathematics places a greater emphasis on sense making, problem solving, reasoning, representation, connections, and communication. History of Mathematics History of Mathematics is a one-semester elective course option for students who have completed AP Calculus or are taking AP Calculus concurrently. It traces the development of major branches of mathematics throughout history, specifically algebra, geometry, number theory, and methods of proofs, how that development was influenced by the needs of various cultures, and how the mathematics in turn influenced culture. The course extends the numbers and counting, algebra, geometry, and data analysis and probability strands from previous courses, and includes a new history strand. -

The Cubic Groups

The Cubic Groups Baccalaureate Thesis in Electrical Engineering Author: Supervisor: Sana Zunic Dr. Wolfgang Herfort 0627758 Vienna University of Technology May 13, 2010 Contents 1 Concepts from Algebra 4 1.1 Groups . 4 1.2 Subgroups . 4 1.3 Actions . 5 2 Concepts from Crystallography 6 2.1 Space Groups and their Classification . 6 2.2 Motions in R3 ............................. 8 2.3 Cubic Lattices . 9 2.4 Space Groups with a Cubic Lattice . 10 3 The Octahedral Symmetry Groups 11 3.1 The Elements of O and Oh ..................... 11 3.2 A Presentation of Oh ......................... 14 3.3 The Subgroups of Oh ......................... 14 2 Abstract After introducing basics from (mathematical) crystallography we turn to the description of the octahedral symmetry groups { the symmetry group(s) of a cube. Preface The intention of this account is to provide a description of the octahedral sym- metry groups { symmetry group(s) of the cube. We first give the basic idea (without proofs) of mathematical crystallography, namely that the 219 space groups correspond to the 7 crystal systems. After this we come to describing cubic lattices { such ones that are built from \cubic cells". Finally, among the cubic lattices, we discuss briefly the ones on which O and Oh act. After this we provide lists of the elements and the subgroups of Oh. A presentation of Oh in terms of generators and relations { using the Dynkin diagram B3 is also given. It is our hope that this account is accessible to both { the mathematician and the engineer. The picture on the title page reflects Ha¨uy'sidea of crystal structure [4]. -

Isometries and the Plane

Chapter 1 Isometries of the Plane \For geometry, you know, is the gate of science, and the gate is so low and small that one can only enter it as a little child. (W. K. Clifford) The focus of this first chapter is the 2-dimensional real plane R2, in which a point P can be described by its coordinates: 2 P 2 R ;P = (x; y); x 2 R; y 2 R: Alternatively, we can describe P as a complex number by writing P = (x; y) = x + iy 2 C: 2 The plane R comes with a usual distance. If P1 = (x1; y1);P2 = (x2; y2) 2 R2 are two points in the plane, then p 2 2 d(P1;P2) = (x2 − x1) + (y2 − y1) : Note that this is consistent withp the complex notation. For P = x + iy 2 C, p 2 2 recall that jP j = x + y = P P , thus for two complex points P1 = x1 + iy1;P2 = x2 + iy2 2 C, we have q d(P1;P2) = jP2 − P1j = (P2 − P1)(P2 − P1) p 2 2 = j(x2 − x1) + i(y2 − y1)j = (x2 − x1) + (y2 − y1) ; where ( ) denotes the complex conjugation, i.e. x + iy = x − iy. We are now interested in planar transformations (that is, maps from R2 to R2) that preserve distances. 1 2 CHAPTER 1. ISOMETRIES OF THE PLANE Points in the Plane • A point P in the plane is a pair of real numbers P=(x,y). d(0,P)2 = x2+y2. • A point P=(x,y) in the plane can be seen as a complex number x+iy. -

Chapter 1 – Symmetry of Molecules – P. 1

Chapter 1 – Symmetry of Molecules – p. 1 - 1. Symmetry of Molecules 1.1 Symmetry Elements · Symmetry operation: Operation that transforms a molecule to an equivalent position and orientation, i.e. after the operation every point of the molecule is coincident with an equivalent point. · Symmetry element: Geometrical entity (line, plane or point) which respect to which one or more symmetry operations can be carried out. In molecules there are only four types of symmetry elements or operations: · Mirror planes: reflection with respect to plane; notation: s · Center of inversion: inversion of all atom positions with respect to inversion center, notation i · Proper axis: Rotation by 2p/n with respect to the axis, notation Cn · Improper axis: Rotation by 2p/n with respect to the axis, followed by reflection with respect to plane, perpendicular to axis, notation Sn Formally, this classification can be further simplified by expressing the inversion i as an improper rotation S2 and the reflection s as an improper rotation S1. Thus, the only symmetry elements in molecules are Cn and Sn. Important: Successive execution of two symmetry operation corresponds to another symmetry operation of the molecule. In order to make this statement a general rule, we require one more symmetry operation, the identity E. (1.1: Symmetry elements in CH4, successive execution of symmetry operations) 1.2. Systematic classification by symmetry groups According to their inherent symmetry elements, molecules can be classified systematically in so called symmetry groups. We use the so-called Schönfliess notation to name the groups, Chapter 1 – Symmetry of Molecules – p. 2 - which is the usual notation for molecules. -

20. Geometry of the Circle (SC)

20. GEOMETRY OF THE CIRCLE PARTS OF THE CIRCLE Segments When we speak of a circle we may be referring to the plane figure itself or the boundary of the shape, called the circumference. In solving problems involving the circle, we must be familiar with several theorems. In order to understand these theorems, we review the names given to parts of a circle. Diameter and chord The region that is encompassed between an arc and a chord is called a segment. The region between the chord and the minor arc is called the minor segment. The region between the chord and the major arc is called the major segment. If the chord is a diameter, then both segments are equal and are called semi-circles. The straight line joining any two points on the circle is called a chord. Sectors A diameter is a chord that passes through the center of the circle. It is, therefore, the longest possible chord of a circle. In the diagram, O is the center of the circle, AB is a diameter and PQ is also a chord. Arcs The region that is enclosed by any two radii and an arc is called a sector. If the region is bounded by the two radii and a minor arc, then it is called the minor sector. www.faspassmaths.comIf the region is bounded by two radii and the major arc, it is called the major sector. An arc of a circle is the part of the circumference of the circle that is cut off by a chord. -

Pose Estimation for Objects with Rotational Symmetry

Pose Estimation for Objects with Rotational Symmetry Enric Corona, Kaustav Kundu, Sanja Fidler Abstract— Pose estimation is a widely explored problem, enabling many robotic tasks such as grasping and manipulation. In this paper, we tackle the problem of pose estimation for objects that exhibit rotational symmetry, which are common in man-made and industrial environments. In particular, our aim is to infer poses for objects not seen at training time, but for which their 3D CAD models are available at test time. Previous X 2 X 1 X 2 X 1 work has tackled this problem by learning to compare captured Y ∼ 2 Y ∼ 2 Y ∼ 2 Y ∼ 2 views of real objects with the rendered views of their 3D CAD Z ∼ 6 Z ∼ 1 Z ∼ Z ∼ 1 ∼ ∼ ∼ ∞ ∼ models, by embedding them in a joint latent space using neural Fig. 1. Many industrial objects such as various tools exhibit rotational networks. We show that sidestepping the issue of symmetry symmetries. In our work, we address pose estimation for such objects. in this scenario during training leads to poor performance at test time. We propose a model that reasons about rotational symmetry during training by having access to only a small set of that this is not a trivial task, as the rendered views may look symmetry-labeled objects, whereby exploiting a large collection very different from objects in real images, both because of of unlabeled CAD models. We demonstrate that our approach different background, lighting, and possible occlusion that significantly outperforms a naively trained neural network on arise in real scenes. -

Symmetry of Graphs. Circles

Symmetry of graphs. Circles Symmetry of graphs. Circles 1 / 10 Today we will be interested in reflection across the x-axis, reflection across the y-axis and reflection across the origin. Reflection across y reflection across x reflection across (0; 0) Sends (x,y) to (-x,y) Sends (x,y) to (x,-y) Sends (x,y) to (-x,-y) Examples with Symmetry What is Symmetry? Take some geometrical object. It is called symmetric if some geometric move preserves it Symmetry of graphs. Circles 2 / 10 Reflection across y reflection across x reflection across (0; 0) Sends (x,y) to (-x,y) Sends (x,y) to (x,-y) Sends (x,y) to (-x,-y) Examples with Symmetry What is Symmetry? Take some geometrical object. It is called symmetric if some geometric move preserves it Today we will be interested in reflection across the x-axis, reflection across the y-axis and reflection across the origin. Symmetry of graphs. Circles 2 / 10 Sends (x,y) to (-x,y) Sends (x,y) to (x,-y) Sends (x,y) to (-x,-y) Examples with Symmetry What is Symmetry? Take some geometrical object. It is called symmetric if some geometric move preserves it Today we will be interested in reflection across the x-axis, reflection across the y-axis and reflection across the origin. Reflection across y reflection across x reflection across (0; 0) Symmetry of graphs. Circles 2 / 10 Sends (x,y) to (-x,y) Sends (x,y) to (x,-y) Sends (x,y) to (-x,-y) Examples with Symmetry What is Symmetry? Take some geometrical object. -

12-5 Worksheet Part C

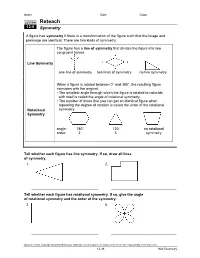

Name ________________________________________ Date __________________ Class__________________ LESSON Reteach 12-5 Symmetry A figure has symmetry if there is a transformation of the figure such that the image and preimage are identical. There are two kinds of symmetry. The figure has a line of symmetry that divides the figure into two congruent halves. Line Symmetry one line of symmetry two lines of symmetry no line symmetry When a figure is rotated between 0° and 360°, the resulting figure coincides with the original. • The smallest angle through which the figure is rotated to coincide with itself is called the angle of rotational symmetry. • The number of times that you can get an identical figure when repeating the degree of rotation is called the order of the rotational Rotational symmetry. Symmetry angle: 180° 120° no rotational order: 2 3 symmetry Tell whether each figure has line symmetry. If so, draw all lines of symmetry. 1. 2. _________________________________________ ________________________________________ Tell whether each figure has rotational symmetry. If so, give the angle of rotational symmetry and the order of the symmetry. 3. 4. _________________________________________ ________________________________________ Original content Copyright © by Holt McDougal. Additions and changes to the original content are the responsibility of the instructor. 12-38 Holt Geometry Name ________________________________________ Date __________________ Class__________________ LESSON Reteach 12-5 Symmetry continued Three-dimensional figures can also have symmetry. Symmetry in Three Description Example Dimensions A plane can divide a figure into two Plane Symmetry congruent halves. There is a line about which a figure Symmetry About can be rotated so that the image and an Axis preimage are identical.