76 Lea Green 0 Introduction V1 Hl.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

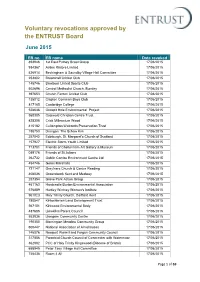

Voluntary Revocations Approved by the ENTRUST Board

Voluntary revocations approved by the ENTRUST Board June 2015 EB no. EB name Date revoked 893946 1st East Putney Scout Group 17/06/2015 934367 Action Kintore Limited 17/06/2015 426914 Beckingham & Saundby Village Hall Committee 17/06/2015 253802 Broomhall Cricket Club 17/06/2015 148746 Broxburn United Sports Club 17/06/2015 502696 Central Methodist Church, Burnley 17/06/2015 397653 Church Fenton Cricket Club 17/06/2015 135012 Clapton Common Boys Club 17/06/2015 817165 Coatbridge College 17/06/2015 528636 Cockpit Hole Environmental Project 17/06/2015 560305 Cotswold Christian Centre Trust 17/06/2015 428308 Crick Millennium Wood 17/06/2015 415182 Cullompton Walronds Preservation Trust 17/06/2015 198753 Drongan: The Schaw Kirk 17/06/2015 257042 Edinburgh, St. Margaret's Church of Scotland 17/06/2015 157927 Electric Storm Youth Limited 17/06/2015 713701 Friends of Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum 17/06/2015 089176 Friends of St Julians 17/06/2015 262732 Goblin Combe Environment Centre Ltd 17/06/2015 454746 Gores Marshalls 17/06/2015 721147 Greyfriars Church & Centre Reading 17/06/2015 408036 Groundwork Kent and Medway 17/06/2015 257354 Grove Park Action Group 17/06/2015 461163 Hardcastle Burton Environmental Association 17/06/2015 576889 Hartley Wintney Women's Institute 17/06/2015 961023 Holy Trinity Church, Dartford Kent 17/06/2015 780547 Kinlochleven Land Development Trust 17/06/2015 567101 Kirkwood Environmental Body 17/06/2015 487685 Limekilns Parent Council 17/06/2015 553836 Llangwm Community Centre 17/06/2015 190350 Mornington Meadow -

Placenamesofliverpool.Pdf

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES LIVERPOOL DISTRICT PLACE-NAMES. ^Liverpool . t/tai Saxon hive.'—Matthew Arnold. ' Liverpool . the greatest covunercial city in the world' Nathaniel Hawthorne. ' That's a great city, and those are the lamps. It's Liverpool.' ' ' Christopher Tadpole (A. Smith). ' In the United Kingdom there is no city luhichfrom early days has inspired me with so -much interest, none which I zvould so gladly serve in any capacity, however humble, as the city of Liverpool.' Rev. J. E. C. Welldon. THE PLACE-NAMES OF THE LIVERPOOL DISTRICT; OR, ^he l)i0torj) mxb Jttciining oi the ^oral aiib llibev ^mncQ oi ,S0xitk-to£0t |£ancashtrc mxlb oi SEirral BY HENRY HARRISON, •respiciendum est ut discamus ex pr^terito. LONDON : ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 1898. '^0 SIR JOHN T. BRUNNER, BART., OF "DRUIDS' CROSS," WAVERTREE, MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE NOKTHWICH DIVISION OF CHESHIRE, THIS LITTLE VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. 807311 CONTENTS. PACE INTRODUCTION --.--. 5 BRIEF GLOSSARY OF SOME OF THE CHIEF ENGLISH PLACE-NAME COMPONENTS - - - "17 DOMESDAY ENTRIES - - - - - 20 LINGUISTIC ABBREVIATIONS, ETC. - - - 23 LIVERPOOL ------- 24 HUNDRED OF WEST DERBY - - - "33 HUNDRED OF WIRRAL - - - - - 75 LIST OF WORKS QUOTED - - - - - lOI INTRODUCTION. This little onomasticon embodies, I believe, the first at- tempt to treat the etymology of the place-names of the Liverpool district upon a systematic basis. In various local and county histories endeavours have here and there been made to account for the origin of certain place-names, but such endeavours have unfortunately only too frequently been remarkable for anything but philological, and even topographical, accuracy. -

Rainford Conservation Area Appraisal.Pdf

Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal July 2008 Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal Located immediately north of St Helens town, Rainford is well known for its indus- trial past. It was the location of sand mining for the glass factories of St Helens and was a major manufacturer of clay smoking pipes, firebricks and earthenware cruci- bles. Natural resources brought fame and prosperity to the village during the late eight- eenth and early nineteenth centuries. The resulting shops, light industries and sub- sequent dwelling houses contribute to Rainford’s distinct character. In recognition of its historical significance and architectural character, a section of Rainford was originally designated as a conservation area in 1976. Rainford re- mains a ‘typical’ English country village and this review is intended to help preserve and enhance it. Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal Contents Content Page 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Policy Context 4 3.0 Location and Setting 7 4.0 Historical Background 10 5.0 Character Area Analysis 16 6.0 Distinctive Details and Local Features 27 7.0 Extent of Loss, Intrusion and Damage 28 8.0 Community Involvement 30 9.0 Boundary Changes 31 10.0 Summary of Key Character 35 11.0 Issues 38 12.0 Next Steps 41 References 42 Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal— Rainford I & II Conservation Area Appraisal 1.0 Introduction 1.0 Introduction Rainford is a bustling linear village between Ormskirk and St Helens in Merseyside. -

Uses of Historic Buildings for Residential Purposes (Colliers 2015)

= Use of Historic Buildings for Residential Purposes SCOPING REPORT – DRAFT 3 JULY 2015 PREPARED FOR HISTORIC ENGLAND COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL PROPERTY CONSULTANTS LIMITED Company registered in England and Wales no. 7996509 Registered office: 50 George St London W1U 7DY Tel: +44 20 7935 4499 www.colliers.com/uk [email protected] Version Control Status FINAL Project ID JM32494 Filename/Document ID Use of Historic Buildings for Residential 160615 Last Saved 23 October 2015 Owner David Geddes COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 2 of 66 use use of historic buildings for residential purposes DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 4 2 Literature Review 5 / 2.1 Introduction 5 2015 2.2 English Heritage / Historic England 5 - 10 - 2.3 General Issues 19 23 13:01 2.4 Case Study Orientated Books 21 2.5 Journal Articles 25 2.6 Architectural Journal Building Reports 25 3 Case Studies 26 4 Main Developers 53 4.1 Kit Martin CBE 53 4.2 Urban Splash 54 4.3 City and Country 55 4.4 PJ Livesey Group 57 4.5 Others 57 5 Conclusions 59 5.1 General 59 5.2 Country Houses 60 5.3 Large Instiutions 61 5.4 Mills and Factories 62 5.5 Issues that Could be Explored in Stage 2 62 COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 3 of 66 use use of historic buildings for residential purposes DRAFT 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this study is to investigate what might be done by the public sector to encourage conversion of large heritage assets at risk to residential use. It complements a survey that Historic England has commissioned of owners of historic buildings used for residential purposes, and also a review of the work of / Building Preservation Trusts in converting historic buildings for residential use. -

Churchwardens' Accounts of Walton-On-The-Hill 1627-67

The Record Societ}' of Lancashire and Cheshire Volume 141: start THE RECORD SOCIETY OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE FOUNDED TO TRANSCRIBE AND PUBLISH ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS RELATING TO THE TWO COUNTIES VOLUME CXLI The Society wishes to acknowledge with gratitude the support given towards publication by Lancashire County Council © The Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire E.M.E. Ramsay A.J. Maddock ISBN 0 902593 68 4 Printed in Great Britain by Arrowsmith, Bristol THE CHURCHWARDENS’ ACCOUNTS OF WALTQN-ON-THE-HILL, LANCASHIRE 1627-1667 Transcribed and edited by Esther M.E. Ramsay and Alison J. Maddock PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY 2005 FOR THE SUBSCRIPTION YEAR 2003 COUNCIL AND OFFICERS FOR THE YEAR 2ffl©3 President Jenny Kermode, BA., Ph.D. (from September 2003 J.H. Pepler, M.A., D.A.A., c/o Cheshire Record Office, Duke Street, Chester CHI 1RL) Hon. Council Secretary Dorothy J. Clayton, M.A., Ph.D., A.L.A., F.R.Hist.S., c/o John Rylands University Library of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M l3 9PP Hon. Membership Secretary Maureen Barber, B.A., D.L.A., 7 Rosebank, Lostock, Bolton BL6 4PE Hon. Treasurer and Publications Secretary Fiona Pogson, B.A., Ph.D., c/o Department of History, Liverpool Hope University College, Hope Park, Liverpool L16 9JD Hon. General Editor Peter McNiven, M.A., Ph.D., F.R.Hist.S., The Vicarage, 1 Heol Mansant, Pontyates, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire SA15 5SB Other Members of the Council Diana E.S. Dunn, B.A., D.Ar.Studies B.W. Quintrell, M.A., Ph.D., F.R.Hist.S. -

Merseyside Record Office

GB 1072 M347 PSK Merseyside Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 27828 JA The National Archives Merseyside Record Office M347 PSK: KIRKDALE PETTY SESSIONS Accession Number 2004/1 Description 1. Minute Books, 1927-1964 2. Court Registers, 1885-1955 3. Juvenile Court Registers, 1941-1955 4. Warrant Books, 1930-1942 5. Maintenance Orders, 1946-1955 6. Financial Records, 1949-1957 7. Licensing Registers, 1903-1962 8. Licensing Plans, 1903-1961 9. West Derby Hundred Sessions Magistrates Attendance Book, 1902-1935 Covering dates 1885-1962 Administrative history Courts of Petty Sessions evolved from the exercise of summary jurisdiction by justices outside Quarter Sessions. Regular divisional meetings of two or more justices appeared gradually in the eighteenth century. By the end of that century, such meetings were instituted at stated times and places and an act of 1828 required the Quarter Sessions to define Petty Session Districts. The business of the court of petty sessions was both judicial and administrative and the modern magistrates court has inherited these functions. The judicial side deals with minor offences - both adult and juvenile. Magistrates also preside over the Youth Courts which are especially constituted with jurisdiction limited to proceedings for custody, maintenance, adoption, guardianship and family protection orders. Administrative duties of magistrates include the licensing of public houses, licensed victuallers, clubs, restaurants, cinemas, lodging houses, premises licensed for liquor, music, dancing etc. and registered premises (explosives). Before 1974, petty sessions courts (also known as magistrates courts) were of two types: 1. -

Whittle Hall Farm, Littledale Road, Great Sankey, Warrington

Whittle Hall Farm, Littledale Road, Great Sankey, Warrington Heritage Appraisal Oxford Archaeology North July 2015 Red Apple Design Ltd Issue No: 2015-16/1666 OA North Job No: L10884 NGR: 357003 389112 Document Title: Whittle Hall Farm, Littledale Road, Great Sankey, Warrington Document Type: Heritage Appraisal Client Name: Red Apple Design Ltd Issue Number: 2015-16/1666 OA North Job Number: L10884 National Grid Reference: 357003 389112 Prepared by: Ian Miller Signed Position: Senior Project Manager Date: July 2015 Approved by: Alan Lupton Signed . Position: Operations Manager Date: July 2015 Oxford Archaeology North © Oxford Archaeology Ltd (2015) Mill 3 Janus House Moor Lane Mill Osney Mead Moor Lane Oxford Lancaster LA1 1GF OX2 0EA t: (0044) 01524 541000 t: (0044) 01865 263800 f: (0044) 01524 848606 f: (0044) 01865 793496 w: www.oxfordarch.co.uk e: [email protected] Oxford Archaeological Unit Limited is a Registered Charity No: 285627 Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Oxford Archaeology Ltd being obtained. Oxford Archaeology Ltd accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person/party using or relying on the document for such other purposes agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm their agreement to indemnify Oxford Archaeology for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. -

Biennial Conservation Report 2009-11 1

GHEU/ English Heritage BIENNIAL Government Historic Estates Unit Government CONSERVATION REPORT The Government Historic Estate 2009-2011 Compiled by the Government Historic Estates Unit Front cover and above: Mosaic detail, St George’s Garrison Church, Woolwich. Back cover: Detail of the Victoria Cross Memorial, St George’s Garrison Church, Woolwich. BIENNIAL CONSERVATION REPORT 2009-11 1 CONTENTS Section 1.0 Introduction 3 Section 2.0 Progress with stewardship 4 2.1 Changes to the management of departments’ estates 4 2.2 The Protocol 4 2.3 Specialist conservation advice 4 2.4 Conservation management plans 5 2.5 Condition surveys and asset management 5 2.6 Funding and resources 6 2.7 Heritage at risk 6 2.8 Buildings at risk 7 2.9 Field monuments at risk 7 2.10 Historic parks and gardens 8 2.11 Recording 8 Section 3.0 Current initiatives 9 3.1 National planning policy and guidance 9 3.2 Heritage Partnership Agreements 9 3.3 Standing clearances 9 3.4 National Heritage Protection Plan 10 3.5 Heritage data 10 3.6 Maritime heritage 12 Section 4.0 Disposals and transfers 13 4.1 Disposals on the MOD estate 13 4.2 Disposals on the civil estate 14 Section 5.0 Government Historic Estates Unit 15 5.1 Team structure 15 5.2 Informal site-specific advice 15 5.3 Statutory site-specific advice 15 5.4 General conservation advice 16 5.5 Published guidance 16 5.6 Conservation training 17 Continued 2 BIENNIAL CONSERVATION REPORT 2009-11 CONTENTS continued Tables 18 A Progress by departments in complying with the DCMS Protocol 18 B Progress by other historic -

The Domesday Survey of South Lancashire

THE DOMESDAY SURVEY OF SOUTH LANCASHIRE. By J. H. Lnmby, B.A., Charles IJeard Historical Research Exhibitioner, University College, Liverpool. Read i8ih January, 1900. HE Domesday Survey of South Lancashire is T included in that of Cheshire, under the sub- title Inter Ripam et Mersham. It consists merely of three columns and nine lines of a fourth. Com pared with the treatment afforded to Cheshire this seems scant courtesy, but we may find that the task of the Commissioners and of the scribe who made the final abstract of the original returns, was simplified considerably by the broad lines of the history of the district during the 20 years preceding the accepted date of the Inquest. The first column is wholly concerned with the hundred of " Derbei," of which some 40 vills are enumerated. The second column proceeds with an account of the customs of the same hundred, customs that, in whole or in part, related also to the other hundreds, unless we except " Walintune," which would be rash. Derby Hundred T. R. W., and Newton and Warrington Hundreds T. R. E. and T. R. W., are treated in the PLATE XIII. H. S. OF L& C. NTER RIPAM ET MERSHAM The Idenhficahons of Ohegnmele. Erengermeles and Mele are MTarrers. B L A C H (B URN U N D R E D i I v a ) xxviii liba/i homines], pro xxviii Maneriis o iHu nnicoh La land Si)va] Ofe^rimele (ONn^emele) LAILAND HUNDRED xii car. pro xii Manerns Erenqermeles /" . <~'' Merrelun * . Hirlefun \ (Hiretun) HUNDRED xxi bereuuich (p r° xx,i Maneriis cum i bereuuiob'"" \ ; f Si lv)ae) .pro iii Maneriis v I [ a d e c 11 u e ': (Silva) / ^ V MCl6 . -

The Great Civil War in Lancashire

LIBRARY EXCHANGE. WITH THE COMPLIMENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY COUNCIL . Acknowledgments and publications sent in exchange should be addressed to THE LIBRARIAN , THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER . The Great Civil War in Lancashire (1642-1651) BY ERNEST BROXAP, M.A. PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER HISTORICAL SERIES, No. X The Great Civil War in Lancashire SHERRATT & HUGHES Publishers to the Victoria University of Manchester> Manchester: 34 Cross Street> London: 33 Soho Square W. [Pg i] [Pg ii] [Pg iii] The Great Civil War in Lancashire (1642-1651) BY ERNEST BROXAP, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1910 CONTENTS Preface ix Authorities xi Introduction 1 Chapter I. Preliminaries 9 " II. The Leaders on Both Sides 23 " III. The Siege of Manchester 37 " IV. First Operations of the Manchester Garrison 53 " V. The Crisis. January-June, 1643 67 " VI. Remaining Events of 1643: and the First Siege of Lathom House 89 " VII. Prince Rupert in Lancashire 115 " VIII. End of the First Civil War 135 " IX. The Second Civil War: Battle of Preston 159 " X. The Last Stand: Battle of Wigan Lane: Trial and Death of the Earl of Derby 177 Index 205 [Pg viii] MAPS AND PLANS Map. Lancashire, to illustrate the Civil War . Frontispiece Plans in Text. I. Manchester and Salford in 1650 see page 43 (Reproduced from Owens College Historical Essays, p. 383). II. The Spanish Ship in the Fylde, March, 1642-3 see page 72 III. The Battle of Whalley, April, 1643 see page 82 IV. Liverpool in 1650 see page 128 (Reproduced from Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, Session 6, 1853-4, Vol. -

D. A. Higgins 125 Once Broken and They Survive Well in the Ground

D. A. Higgins 125 Merseyside Clay Tobacco Pipes, c1600-1750 once broken and they survive well in the ground, making them an ideal subject to study archaeologically. The D. A. Higgins earliest recognisable forms date from c1580-1610 and had very small bowls since tobacco during this period Introduction was an expensive luxury that had to be either imported from the New World or grown in small quantities in This paper briefly outlines the introduction of tobacco carefully tended gardens. These first pipes are rare to Britain and the spread of smoking, before looking nationally and they tend to be associated with wealthy at the pipes made and used in and around Merseyside households or ‘high status’ sites. It does appear, however, from about 1600-1750. The first part provides a that they are most frequently found in the south west context in which to set the Merseyside evidence. The of England and these early pipes were certainly being early industry centred on Chester is examined to show produced in or near some of the ports in that region, for how pipemaking established itself in the region and example Plymouth. This association may be partly due how a distinctive style was established in that city. In to tobacco being more readily available at ports with contrast, there is little evidence for early pipemaking shipping connections to the New World and partly due to in Lancaster or in the north of Lancashire and it is only the influence of wealthy individuals from the area such in the south of the old county, and in particular in the as Sir Walter Raleigh, whose enthusiasm for smoking is Merseyside area, that a flourishing industry developed. -

Knowsley Historic Settlement Study

Knowsley Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study................................................................... 1 Cronton ..................................................................................................................... 4 Halewood .................................................................................................................. 7 Huyton..................................................................................................................... 10 Kirkby...................................................................................................................... 13 Knowsley................................................................................................................. 16 Prescot.................................................................................................................... 19 Roby........................................................................................................................ 24 Simonswood............................................................................................................ 27 Tarbock ................................................................................................................... 30 Thingwall................................................................................................................