D. A. Higgins 125 Once Broken and They Survive Well in the Ground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

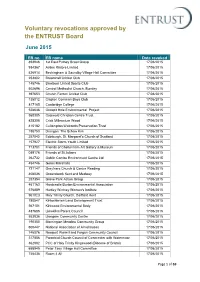

Voluntary Revocations Approved by the ENTRUST Board

Voluntary revocations approved by the ENTRUST Board June 2015 EB no. EB name Date revoked 893946 1st East Putney Scout Group 17/06/2015 934367 Action Kintore Limited 17/06/2015 426914 Beckingham & Saundby Village Hall Committee 17/06/2015 253802 Broomhall Cricket Club 17/06/2015 148746 Broxburn United Sports Club 17/06/2015 502696 Central Methodist Church, Burnley 17/06/2015 397653 Church Fenton Cricket Club 17/06/2015 135012 Clapton Common Boys Club 17/06/2015 817165 Coatbridge College 17/06/2015 528636 Cockpit Hole Environmental Project 17/06/2015 560305 Cotswold Christian Centre Trust 17/06/2015 428308 Crick Millennium Wood 17/06/2015 415182 Cullompton Walronds Preservation Trust 17/06/2015 198753 Drongan: The Schaw Kirk 17/06/2015 257042 Edinburgh, St. Margaret's Church of Scotland 17/06/2015 157927 Electric Storm Youth Limited 17/06/2015 713701 Friends of Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum 17/06/2015 089176 Friends of St Julians 17/06/2015 262732 Goblin Combe Environment Centre Ltd 17/06/2015 454746 Gores Marshalls 17/06/2015 721147 Greyfriars Church & Centre Reading 17/06/2015 408036 Groundwork Kent and Medway 17/06/2015 257354 Grove Park Action Group 17/06/2015 461163 Hardcastle Burton Environmental Association 17/06/2015 576889 Hartley Wintney Women's Institute 17/06/2015 961023 Holy Trinity Church, Dartford Kent 17/06/2015 780547 Kinlochleven Land Development Trust 17/06/2015 567101 Kirkwood Environmental Body 17/06/2015 487685 Limekilns Parent Council 17/06/2015 553836 Llangwm Community Centre 17/06/2015 190350 Mornington Meadow -

Uses of Historic Buildings for Residential Purposes (Colliers 2015)

= Use of Historic Buildings for Residential Purposes SCOPING REPORT – DRAFT 3 JULY 2015 PREPARED FOR HISTORIC ENGLAND COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL PROPERTY CONSULTANTS LIMITED Company registered in England and Wales no. 7996509 Registered office: 50 George St London W1U 7DY Tel: +44 20 7935 4499 www.colliers.com/uk [email protected] Version Control Status FINAL Project ID JM32494 Filename/Document ID Use of Historic Buildings for Residential 160615 Last Saved 23 October 2015 Owner David Geddes COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 2 of 66 use use of historic buildings for residential purposes DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 4 2 Literature Review 5 / 2.1 Introduction 5 2015 2.2 English Heritage / Historic England 5 - 10 - 2.3 General Issues 19 23 13:01 2.4 Case Study Orientated Books 21 2.5 Journal Articles 25 2.6 Architectural Journal Building Reports 25 3 Case Studies 26 4 Main Developers 53 4.1 Kit Martin CBE 53 4.2 Urban Splash 54 4.3 City and Country 55 4.4 PJ Livesey Group 57 4.5 Others 57 5 Conclusions 59 5.1 General 59 5.2 Country Houses 60 5.3 Large Instiutions 61 5.4 Mills and Factories 62 5.5 Issues that Could be Explored in Stage 2 62 COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 3 of 66 use use of historic buildings for residential purposes DRAFT 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this study is to investigate what might be done by the public sector to encourage conversion of large heritage assets at risk to residential use. It complements a survey that Historic England has commissioned of owners of historic buildings used for residential purposes, and also a review of the work of / Building Preservation Trusts in converting historic buildings for residential use. -

76 Lea Green 0 Introduction V1 Hl.Indd

Journal of the Merseyside Archaeological Society Volume 14 2012 A Yeoman Farm in St Helens Excavations at Big Lea Green Farm, Sutton, 2002 A. C. Towle and J. I. Speakman With contributions by M. H. Adams, D. A. Higgins, D. Jaques, Q. Mould, R. A. Philpott and E. Simmons iii Contents Figures v Tables vii Acknowledgements viii Summary ix 1: Introduction 1 2. The Archaeological Excavations 13 3. Environmental Report 32 Archaeobotanical Analysis and Report 32 Vertebrate Remains 37 4: The Finds 41 Pottery 41 Clay Tobacco Pipes and Other Pipe-Clay Objects 80 Leather 105 Glass and Vitreous Materials 107 Stone Architectural Fragments 111 5: Discussion 112 6: Conclusions 115 References 116 Appendix A: Historical Documents Relating to Lea Green 121 Appendix B: Summary of Clay Tobacco Pipes by Context 127 iv Summary In 2002 the construction of a regional distribution of drains. Domestic pottery continued to be deposited centre by Somerfield plc provided an opportunity for into a garden soil behind the farmhouse. Between 1826 archaeologists from Liverpool Museum to excavate and 1849 a wide shallow ditch was excavated defining and survey a late medieval and post-medieval farm the south-west corner of the farm. This ditch had the at Lea Green, near St Helens. Documentary research appearance of a medieval moat, but proved to be a 19th- had already established the occupation of Big Lea century ditch/landscape feature. Green Farm during the late 17th century by Bryan Lea, ‘yeoman of Sutton’, and it probably corresponded to The farm was transformed during the late 19th century lands held by Thurstan de Standish in the 14th century. -

Whittle Hall Farm, Littledale Road, Great Sankey, Warrington

Whittle Hall Farm, Littledale Road, Great Sankey, Warrington Heritage Appraisal Oxford Archaeology North July 2015 Red Apple Design Ltd Issue No: 2015-16/1666 OA North Job No: L10884 NGR: 357003 389112 Document Title: Whittle Hall Farm, Littledale Road, Great Sankey, Warrington Document Type: Heritage Appraisal Client Name: Red Apple Design Ltd Issue Number: 2015-16/1666 OA North Job Number: L10884 National Grid Reference: 357003 389112 Prepared by: Ian Miller Signed Position: Senior Project Manager Date: July 2015 Approved by: Alan Lupton Signed . Position: Operations Manager Date: July 2015 Oxford Archaeology North © Oxford Archaeology Ltd (2015) Mill 3 Janus House Moor Lane Mill Osney Mead Moor Lane Oxford Lancaster LA1 1GF OX2 0EA t: (0044) 01524 541000 t: (0044) 01865 263800 f: (0044) 01524 848606 f: (0044) 01865 793496 w: www.oxfordarch.co.uk e: [email protected] Oxford Archaeological Unit Limited is a Registered Charity No: 285627 Disclaimer: This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Oxford Archaeology Ltd being obtained. Oxford Archaeology Ltd accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person/party using or relying on the document for such other purposes agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm their agreement to indemnify Oxford Archaeology for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. -

Biennial Conservation Report 2009-11 1

GHEU/ English Heritage BIENNIAL Government Historic Estates Unit Government CONSERVATION REPORT The Government Historic Estate 2009-2011 Compiled by the Government Historic Estates Unit Front cover and above: Mosaic detail, St George’s Garrison Church, Woolwich. Back cover: Detail of the Victoria Cross Memorial, St George’s Garrison Church, Woolwich. BIENNIAL CONSERVATION REPORT 2009-11 1 CONTENTS Section 1.0 Introduction 3 Section 2.0 Progress with stewardship 4 2.1 Changes to the management of departments’ estates 4 2.2 The Protocol 4 2.3 Specialist conservation advice 4 2.4 Conservation management plans 5 2.5 Condition surveys and asset management 5 2.6 Funding and resources 6 2.7 Heritage at risk 6 2.8 Buildings at risk 7 2.9 Field monuments at risk 7 2.10 Historic parks and gardens 8 2.11 Recording 8 Section 3.0 Current initiatives 9 3.1 National planning policy and guidance 9 3.2 Heritage Partnership Agreements 9 3.3 Standing clearances 9 3.4 National Heritage Protection Plan 10 3.5 Heritage data 10 3.6 Maritime heritage 12 Section 4.0 Disposals and transfers 13 4.1 Disposals on the MOD estate 13 4.2 Disposals on the civil estate 14 Section 5.0 Government Historic Estates Unit 15 5.1 Team structure 15 5.2 Informal site-specific advice 15 5.3 Statutory site-specific advice 15 5.4 General conservation advice 16 5.5 Published guidance 16 5.6 Conservation training 17 Continued 2 BIENNIAL CONSERVATION REPORT 2009-11 CONTENTS continued Tables 18 A Progress by departments in complying with the DCMS Protocol 18 B Progress by other historic -

LATHOM PARK GARDENS, LATHOM Lancashire

LATHOM PARK GARDENS, LATHOM Lancashire Archaeological Evaluation Report Oxford Archaeology North February 2011 Lathom Park Trust Issue No: 2010-11/1143 OA North Job No: L10169 NGR: SD 4602 0914 Lathom Park Gardens, West Lancashire: Archaeological Evaluation Report 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 5 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Circumstances of Project................................................................................. 7 1.2 Aims and Objectives ....................................................................................... 8 2. HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND........................................... 10 2.1 Location and Geology................................................................................... 10 2.2 Historical Background................................................................................... 10 2.3 Archaeological Background .......................................................................... 14 3. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................... 17 3.1 Geophysical Survey ...................................................................................... 17 3.2 Trial Trenches.............................................................................................. -

List of Monographs August 2021

Oxford Archaeology List of Monographs August 2021 Oxford Archaeology – List of Monographs 2021 Gregory, R, Arrowsmith, P, Miller, I, and Nevell, M, 2021 Farmers and Weavers: Investigation at Kingsway Buisiness Park and Cutacre Country Park, Greater Manchester , Lancaster Imprints 29, Lancaster 2020 Bradley, J, and Rowland, S, 2020 Brothers Minor: Lancashire's Lost Franciscans: Investigations at Preston Friary 1991 and 2007 , Lancaster Imprints 28 , Lancaster Brown, R, Teague, S, Loe, L, Sudds, B, and Popescu, E, 2020 Excavations at Stoke Quay, Ipswich. Southern Gipeswic and the parish of St Augustine , East Anglian Archaeology 172 Dodd, A, Mileson, S, and Webley, L, (eds) 2020 The archaeology of Oxford in the 21st century: Investigations in the city by Oxford Archaeology, 2006-2016 , Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society Occasional Paper 1, Oxford Fairman, A, Teague, S, and Butler, J, 2020 Bridging the past: Life in medieval and post-medieval Southwark. Excavations along the route of Thameslink Borough Viaduct and at London Bridge Station , OAPCA Thameslink Monograph 2, Oxford/London Wenban-Smith, F, Stafford, E, Bates, M, and Parfitt, S, 2020 Prehistoric Ebbsfleet: Excavations and research in advance of High Speed 1 and South Thameside Development Route 4, 1989-2003 , Oxford Wessex Archaeology Monograph 7 2019 Bell, B, Cove, S, Day, K, Gregory, RA, Kingston, E, Lydon, S, and Matthiessen, P, 2019 High life in the uplands: the Duddon Dig Project , Lancaster [short popular booklet] Biddulph, E, Brady, K, Simmonds, A, and Foreman, S, 2019 Berryfields. Iron Age settlement and a Roman bridge, field system and settlement along Akeman Street near Fleet Marston, Buckinghamshire , Oxford Archaeology Monograph 30 , Oxford Forde, D, Munby, J, and Scott, I, 2019 Torre Abbey, Devon: The archaeology of the Premonstratensian abbey , Oxford Archaeology Monograph 29, Oxford Gregory, RA, 2019 Cutacre. -

South-West Lancashire Place-Names

SOUTH-WEST LANCASHIRE PLACE-NAMES BY SIMEON POTTER, M.A., B.LITT., PH.D. Read at Crosby 25 April 1959 HE undulating coastal plain between the rivers Ribble and TMersey, now so densely peopled, was sparsely inhabited in the centuries before the Romans came. Small hunting-fishing communities led a precarious existence in forest, moor and fen. (1) They spoke that variety of P-Celtic (British, Brythonic, or Brittonic as Kenneth Jackson prefers to call it) (2) which is still preserved in such river-names as Alt, of obscure origin; Douglas "black stream" (Br. dubo- "black" + glassjo- "stream")'31 and Glaze (Br. glasto- "bluish green"). The Sankey, which falls into the Mersey near Warrington, and its tributary Goyt, like the Ribble itself, have Brittonic names of doubtful provenance. Dearth of early forms prohibits us from proffering valid etymologies. (4) On the other hand, some river-names are Old English, notably Mersey mxres ea "boundary river" and Tawd, a back-formation from Tawdford OA xt pxm aldan forda "at the old ford", now Tawdbridge. Eller Beck "alder brook", a tributary of the Douglas, is Scandinavian. Many Roman names like Mamucium, surviving in the first element of Man-chester, are also based on prehistoric British tribal names. (5) Through Mamucium passed the Roman road from Aquae (Buxton) to Bremetennacum (Ribchester), Gala- cum (Overborough) and so on to Luguvalium (Carlisle). Another road from Condate (Northwich) crossed the Mersey at Wilderspool near Warrington and then led north through Coccium (Wigan) to Lancaster. (6) These last names Coccium 111 The following abbreviations should be noted: Br. -

NPA Bibliography

PUBLICATIONS HELD The following bibliography lists those publications and off prints held by the National Pipe Archive as of April 2017. The bibliography is divided into four main sections; UK, World (which are site specific), Wreck Sites, and tobacco/smoking related, which are not site specific. The UK section is organised in alphabetical order by county; the world section is in alphabetical order by country order. Wherever possible a complete bibliographic reference has been given. In some cases, however, the archive does not hold all the information, such as volume number and page number. In those instances, an effort has been made to provide as much information as possible so that the reference is usable. Each entry is followed by an NPA accession code, for example LIVNP 1997.17.2, this refers back to the pipe filing system and will help to locate each article. The current list comprises all the published material held by the NPA. Please note that this is a working document and is constantly being updated. In future editions of this list it is hoped to include all the overseas publications, books, theses and trade catalogues held by the NPA. In addition to those articles listed below the NPA holds files on clay tobacco pipes from over 380 sites across the British Isles. These include general details of pipes from whole counties to information about individual find spots. To search the bibliography, use the “find” command by pressing Ctrl F, then type in your key word or subject. 1 PART 1: UK (Site specific) Jersey Avon England (general)