Arxiv:1911.08493V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 20 Feb 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves Manual

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves An AAVSO course for the Carolyn Hurless Online Institute for Continuing Education in Astronomy (CHOICE) This is copyrighted material meant only for official enrollees in this online course. Do not share this document with others. Please do not quote from it without prior permission from the AAVSO. Table of Contents Course Description and Requirements for Completion Chapter One- 1. Introduction . What are variable stars? . The first known variable stars 2. Variable Star Names . Constellation names . Greek letters (Bayer letters) . GCVS naming scheme . Other naming conventions . Naming variable star types 3. The Main Types of variability Extrinsic . Eclipsing . Rotating . Microlensing Intrinsic . Pulsating . Eruptive . Cataclysmic . X-Ray 4. The Variability Tree Chapter Two- 1. Rotating Variables . The Sun . BY Dra stars . RS CVn stars . Rotating ellipsoidal variables 2. Eclipsing Variables . EA . EB . EW . EP . Roche Lobes 1 Chapter Three- 1. Pulsating Variables . Classical Cepheids . Type II Cepheids . RV Tau stars . Delta Sct stars . RR Lyr stars . Miras . Semi-regular stars 2. Eruptive Variables . Young Stellar Objects . T Tau stars . FUOrs . EXOrs . UXOrs . UV Cet stars . Gamma Cas stars . S Dor stars . R CrB stars Chapter Four- 1. Cataclysmic Variables . Dwarf Novae . Novae . Recurrent Novae . Magnetic CVs . Symbiotic Variables . Supernovae 2. Other Variables . Gamma-Ray Bursters . Active Galactic Nuclei 2 Course Description and Requirements for Completion This course is an overview of the types of variable stars most commonly observed by AAVSO observers. We discuss the physical processes behind what makes each type variable and how this is demonstrated in their light curves. Variable star names and nomenclature are placed in a historical context to aid in understanding today’s classification scheme. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

![Arxiv:1806.02345V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 18 Feb 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1698/arxiv-1806-02345v2-astro-ph-ga-18-feb-2019-771698.webp)

Arxiv:1806.02345V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 18 Feb 2019

Draft version February 20, 2019 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 12/16/11 PROPER MOTIONS OF MILKY WAY ULTRA-FAINT SATELLITES WITH Gaia DR2 × DES DR1 Andrew B. Pace1,4 and Ting S. Li2,3 1 George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 2 Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, P.O. Box 500, Batavia, IL 60510, USA and 3 Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA Draft version February 20, 2019 ABSTRACT We present a new, probabilistic method for determining the systemic proper motions of Milky Way (MW) ultra-faint satellites in the Dark Energy Survey (DES). We utilize the superb photometry from the first public data release (DR1) of DES to select candidate members, and cross-match them with the proper motions from Gaia DR2. We model the candidate members with a mixture model (satellite and MW) in spatial and proper motion space. This method does not require prior knowledge of satellite membership, and can successfully determine the tangential motion of thirteen DES satellites. With our method we present measurements of the following satellites: Columba I, Eridanus III, Grus II, Phoenix II, Pictor I, Reticulum III, and Tucana IV; this is the first systemic proper motion measurement for several and the majority lack extensive spectroscopic follow-up studies. We compare these to the predictions of Large Magellanic Cloud satellites and to the vast polar structure. With the high precision DES photometry we conclude that most of the newly identified member stars are very metal-poor ([Fe/H] . -

Sydney Observatory Night Sky Map September 2012 a Map for Each Month of the Year, to Help You Learn About the Night Sky

Sydney Observatory night sky map September 2012 A map for each month of the year, to help you learn about the night sky www.sydneyobservatory.com This star chart shows the stars and constellations visible in the night sky for Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra, Hobart, Adelaide and Perth for September 2012 at about 7:30 pm (local standard time). For Darwin and similar locations the chart will still apply, but some stars will be lost off the southern edge while extra stars will be visible to the north. Stars down to a brightness or magnitude limit of 4.5 are shown. To use this chart, rotate it so that the direction you are facing (north, south, east or west) is shown at the bottom. The centre of the chart represents the point directly above your head, called the zenith, and the outer circular edge represents the horizon. h t r No Star brightness Moon phase Last quarter: 08th Zero or brighter New Moon: 16th 1st magnitude LACERTA nd Deneb First quarter: 23rd 2 CYGNUS Full Moon: 30th rd N 3 E LYRA th Vega W 4 LYRA N CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES VULPECULA SAGITTA PEGASUS DELPHINUS Arcturus Altair EQUULEUS SERPENS AQUILA OPHIUCHUS SCUTUM PISCES Moon on 23rd SERPENS Zubeneschamali AQUARIUS CAPRICORNUS E SAGITTARIUS LIBRA a Saturn Centre of the Galaxy Antares Zubenelgenubi t s Antares VIRGO s t SAGITTARIUS P SCORPIUS P e PISCESMICROSCOPIUM AUSTRINUS SCORPIUS Mars Spica W PISCIS AUSTRINUS CORONA AUSTRALIS Fomalhaut Centre of the Galaxy TELESCOPIUM LUPUS ARA GRUSGRUS INDUS NORMA CORVUS INDUS CETUS SCULPTOR PAVO CIRCINUS CENTAURUS TRIANGULUM -

THE CONSTELLATION MUSCA, the FLY Musca Australis (Latin: Southern Fly) Is a Small Constellation in the Deep Southern Sky

THE CONSTELLATION MUSCA, THE FLY Musca Australis (Latin: Southern Fly) is a small constellation in the deep southern sky. It was one of twelve constellations created by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman and it first appeared on a 35-cm diameter celestial globe published in 1597 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of this constellation in a celestial atlas was in Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603. It was also known as Apis (Latin: bee) for two hundred years. Musca remains below the horizon for most Northern Hemisphere observers. Also known as the Southern or Indian Fly, the French Mouche Australe ou Indienne, the German Südliche Fliege, and the Italian Mosca Australe, it lies partly in the Milky Way, south of Crux and east of the Chamaeleon. De Houtman included it in his southern star catalogue in 1598 under the Dutch name De Vlieghe, ‘The Fly’ This title generally is supposed to have been substituted by La Caille, about 1752, for Bayer's Apis, the Bee; but Halley, in 1679, had called it Musca Apis; and even previous to him, Riccioli catalogued it as Apis seu Musca. Even in our day the idea of a Bee prevails, for Stieler's Planisphere of 1872 has Biene, and an alternative title in France is Abeille. When the Northern Fly was merged with Aries by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1929, Musca Australis was given its modern shortened name Musca. It is the only official constellation depicting an insect. Julius Schiller, who redrew and named all the 88 constellations united Musca with the Bird of Paradise and the Chamaeleon as mother Eve. -

Oriontelescopes.Com Oct

THE EVENING SKY FOR OCTOBER, 2014 NORTH Early October — 10 p.m. Mid October — 9 p.m. URSA MAJOR Late October — 8 p.m. Pointers Big Dipper M51 ζ M81 Winter Hexagon2281 M82 κ M101 LYNX BOÖTES URSA μ M37 AURIGA MINOR M I L K Y W A Y DRACO CAMELOPARDALIS M36 Polaris Little Dipper M38 Capella α CORONA 16,17 BOREALIS ε M1 6543 ν M13 SERPENS CAPUT Double M92 Cluster CEPHEUS Keystone M103 ρ 457 Algol β PERSEUS η M52 Aldebaran μ E M34 δ Vega C 7789 ε Double-Double L γ Hyades I M45 CASSIOPEIA ζ HERCULES P Pleiades M39 Deneb LYRA T TRIANGULUM ORION I M31 α C 7243 M57 752 M110 CYGNUS EAST 7000 M29 χ M32 61 M56 (P a M33 6871 th β o ANDROMEDA Albireo f ARIES OPHIUCHUS WEST S LACERTA Summer Triangle u n TAURUS & VULPECULA I.4665 p γ M27 la n 6633 et s) SAGITTA E 70 Q Great Square DELPHINUS U γ A T γ PISCES of Pegasus O ϑ M14 R PEGASUS M15 Altair Uranus α γ ζ SERPENS EQUULEUS CAUDA Mira ο TX AQUILA M I L KM11 Y W A Y SCUTUM M26 ζ M2 M16 ERIDANUS M17 Neptune M18 AQUARIUS α M24 M25 CETUS M28 M22 7293 FORNAX 253 M30 SAGITTARIUS CAPRICORNUS Teapot Fomalhaut M55 SCULPTOR PISCIS AUSTRINUS 0 55 MICROSCOPIUM 0 20 Star magnitudes N IO R TI Moon IL PHOENIX W Phases GRUS –1 012345 FIRST Oct. 1 SOUTH Double star FULL How To Use This Chart Variable star Oct. -

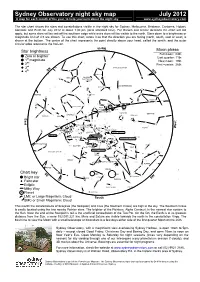

Sydney Observatory Night Sky Map July 2012 a Map for Each Month of the Year, to Help You Learn About the Night Sky

Sydney Observatory night sky map July 2012 A map for each month of the year, to help you learn about the night sky www.sydneyobservatory.com The star chart shows the stars and constellations visible in the night sky for Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra, Hobart, Adelaide and Perth for July 2012 at about 7:30 pm (local standard time). For Darwin and similar locations the chart will still apply, but some stars will be lost off the southern edge while extra stars will be visible to the north. Stars down to a brightness or magnitude limit of 4.5 are shown. To use this chart, rotate it so that the direction you are facing (north, south, east or west) is shown at the bottom. The centre of the chart represents the point directly above your head, called the zenith, and the outer circular edge represents the horizon. URSA MAJOR h rt o N Star brightness Moon phase Full moon: 04th Zero or brighter Last quarter: 11th 1st magnitude nd New moon: 19th 2 First quarter: 26th rd N 3 E Vega CANES VENATICI th LYRA W 4 N BOOTES LEO MINOR CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES CORONA BOOTES BOREALIS COMA BERENICES Arcturus Arcturus SAGITTA SERPENS LEO Regulus Regulus Saturn VIRGO Altair OPHIUCHUS Moon P P on 26th Spica Mars LIBRA ZubenelgenubiZubenelgenubi CORVUS SEXTANS SERPENS CRATER AQUILA SCUTUM E a Antares Antares t s s t Centre of the Galaxy e SCORPIUS HYDRA W LUPUS SAGITTARIUS CENTAURUS NORMA CENTAURUSOmega Centauri TEA POT ANORMAlpha Centauri CORONA AUSTRALIS ANTLIA POINTERSHadar CRUX SOUTHERN CROSS ARA CIRCINUS Alpha Centauri Mimosa CRUX CAPRICORNUS TRIANGULUMTRIANGULUM -

1896A Mary A

1896a Mary A. Orr –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Following the success of their miniature celestial atlas (see 1855, 1866 & 1890c), Gall & Inglis eventually got around to publishing a similar one for the Southern Hemisphere. !is was by Mary Acworth Orr and was closely modelled on the third edition of the original version (see 1890c). As with that work it was issued in hard covers, 140 x 115 mm. and printed soft ones, 135 x 110 mm. !e front of the hard cover version has a very stylish gilt design on blue cloth, with a spine and cover title reminiscent of the original: An Easy guide to the southern stars. Inside, the preface is dated 1896, followed by an index of constellations and an introduction with page numbers. !e charts, each with a page of descriptive text on the verso, are numbered 1/30 but are without titles: Crux Australis; Eridanus/Pavo; Argo Navis; Canis Major; Orion/Lepus; Taurus; Cetus/Pisces; Gemini/Canis Minor; Leo; Hydra/Cancer; Centaurus; Corvus/Virgo; Boötes/Corona Borealis; Serpens/Libra; Scorpio; Sagittarius; Ophiuchus; Hercules/Lyra; Aquila/Delphinus; Piscis Australis/Grus/Phoenix; Triangulum Australe/Ara; Aquarius/ Capricornus; Pegasus; Andromeda/Aries. January/February/March*; April/May/June*; July/August/September*; October/ November/December*; South Polar Stars (index map only, even though a plate had always been included in the original Easy guide); North Polar Constellations (forms the frontispiece and has no index map). Sagittarius Pegasus July/August/September !e twenty-five circular charts have a diameter of 89/98 mm. and the four* rectangular charts, which also have index maps but no text, are 85/7 x 118 mm. -

81 Southern Objects for a 10” Telescope. 0-4Hr 4-8Hr 8-12Hr

81 southern objects for a 10” telescope. 0-4hr NGC55|00h 15m 22s|-39 11’ 35”|33’x 5.6’|Sculptor|Galaxy| NGC104|00h 24m 17s|-72 03’ 30”|31’|Tucana|Globular NGC134|00h 30m 35s|-33 13’ 00”|8.5’x2’|Sculptor|Galaxy| ESO350-40|00h 37m 55s|-33 41’ 20”|1.5’x1.2’|Sculptor|Galaxy|The Cartwheel NGC300|00h 55m 06s|-37 39’ 24”|22’x15.5’|Sculptor|Galaxy| NGC330|00h 56m 27s|-72 26’ 37”|Tucana|1.9’|SMC open cluster| NGC346|00h 59m 14s|-72 09’ 19”|Tucana|5.2’|SMC Neb| ESO351-30|01h 00m 22s|-33 40’ 50”|60’x56’|Sculptor|Galaxy|Sculptor Dwarf NGC362|01h 03m 23s|-70 49’ 42”|13’|Tucana|Globular| NGC2573| 01h 37m 21s|-89 25’ 49”|Octans| 2.0x 0.8|galaxy|polarissima australis| NGC1049|02h 39m 58s|-34 13’ 52”|24”|Fornax|Globular| ESO356-04|02h 40m 09s|-34 25’ 43”|60’x100’|Fornax|Galaxy|Fornax Dwarf NGC1313|03h 18m 18s|-66 29’ 02”|9.1’x6.3’|Reticulum|Galaxy| NGC1316|03h 22m 51s|-37 11’ 22”|12’x8.5’|Fornax|Galaxy| NGC1365|03h 33m 46s|-36 07’ 13”|11.2’x6.2’|Fornax|Galaxy NGC1433|03h 42m 08s|-47 12’ 18”|6.5’x5.9’|Horologium|Galaxy| 4-8hr NGC1566|04h 20m 05s|-54 55’ 42”|Dorado|Galaxy| Reticulum Dwarf|04h 31m 05s|-58 58’ 00”|Reticulum|LMC globular| NGC1808|05h 07m 52s|-37 30’ 20”|6.4’x3.9’|Columba|Galaxy| Kapteyns Star|05h 11m 35s|-45 00’ 16”|Stellar|Pictor|Nearby star| NGC1851|05h 14m 15s|-40 02’ 30”|11’|Columba|Globular| NGC1962group|05h 26m 17s|-68 50’ 28”|?| Dorado|LMC neb/cluster NGC1968group|05h 27m 22s|-67 27’ 36”|12’ for group|Dorado| LMC Neb/cluster| NGC2070|05h 38m 37s|-69 05’ 52”|11’|Dorado|LMC Neb|Tarantula| NGC2442|07h 36m 24s|-69 32’ 38”|5.5’x4.9’|Volans|Galaxy|The meat hook| NGC2439|07h 40m 59s|-31 38’36”|10’|Puppis|Open Cluster| NGC2451|07h 45m 35s|-37 57’ 27”|45’|Puppis|Open Cluster| IC2220|07h 56m 57s|-59 06’ 00”|6’x4’|Carina|Nebula|Toby Jug| NGC2516|07h 58m 29s|-60 51’ 46”|29’|Carina|Open Cluster 8-12hr NGC2547|08h 10m 50s|-49 15’ 39”|20’|Vela|Open Cluster| NGC2736|09h 00m 27s|-45 57’ 49”|30’x7’|Vela|SNR|The Pencil| NGC2808|09h 12m 08s|-64 52’ 48”|12’|Carina|Globular| NGC2818|09h 16m 11s|-36 35’ 59”|9’|Pyxis|Open Cluster with planetary. -

THE SKY TONIGHT Constellation Is Said to Represent Ganymede, the Handsome Prince of Capricornus Troy

- October Oketopa HIGHLIGHTS Aquarius and Aquila In Greek mythology, the Aquarius THE SKY TONIGHT constellation is said to represent Ganymede, the handsome prince of Capricornus Troy. His good looks attracted the attention of Zeus, who sent the eagle The Greeks associated Capricornus Aquila to kidnap him and carry him with Aegipan, who was one of the to Olympus to serve as a cupbearer Panes - a group of half-goat men to the gods. Because of this story, who often had goat legs and horns. Ganymede was sometimes seen as the god of homosexual relations. He Aegipan assumed the form of a fish- also gives his name to one of the tailed goat and fled into the ocean moons of Jupiter, which are named to flee the great monster Typhon. after the lovers of Zeus. Later, he aided Zeus in defeating Typhon and was rewarded by being To locate Aquarius, first find Altair, placed in the stars. the brightest star in the Aquila constellation. Altair is one of the To find Capricornus (highlighted in closest stars to Earth that can be seen orange on the star chart), first locate with the naked eye, at a distance the Aquarius constellation, then of 17 light years. From Altair, scan look to the south-west along the east-south-east to find Aquarius ecliptic line (the dotted line on the (highlighted in yellow on the star chart). star chart). What’s On in October? October shows at Perpetual Guardian Planetarium, book at Museum Shop or online. See website for show times and - details: otagomuseum.nz October Oketopa SKY GUIDE Capturing the Cosmos Planetarium show. -

52-1 Winter 2015

The Valley Skywatcher Official Publication of the Chagrin Valley Astronomical Society PO Box 11, Chagrin Falls, OH 44022 www.chagrinvalleyastronomy.org Founded 1963 C ONTENTS O F F I C E R S F O R 2 0 1 5 Articles President Marty Mullet Why Are You Here? 2 Vice President Ian Cooper A New Telescope Comes to Indian Hill 2 Treasurer Steve Fishman Regular Features Secretary Christina Gibbons Astrophotography 4 Observer’s Log 8 Directors of Observations Bob Modic Mike Hambrecht President’s Corner 11 Constellation Quiz 11 Observatory Director Ray Kriedman Reflections 12 Historian Dan Rothstein Notes & News 13 Editor Ron Baker Lunar Eclipse on October 8, 2014 at 6:54 am EDT. Photo by CVAS member Steve Fishman The Valley Skywatcher • Winter 2015 • Volume 52-1 • Page 1 Why are you here? By Marty Mullet One evening last year, I was sitting on my deck absent- and introduce them to astronomy. Over the years, my mindedly scanning the stars when my eye caught the telescopes got bigger (as did my waistline), and my Great Square of Pegasus rising in the east. I’d seen the observing skills improved. I discovered CVAS and my Great Square countless times before, but for some spark became a blaze. I found myself enjoying reason on this occasion my mind went back to 1980 and outreach and public events, and I began sharing the the first time I’d noticed it. That’s when it hit me: These eyepiece with others, explaining what little I know and four stars that looked like a baseball diamond first lit the learning from those who know more.