'Welsh' Mining Communities of Currawang and Frogmore In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sumo Has Landed in Regional NSW! May 2021

Sumo has landed in Regional NSW! May 2021 Sumo has expanded into over a thousand new suburbs! Postcode Suburb Distributor 2580 BANNABY Essential 2580 BANNISTER Essential 2580 BAW BAW Essential 2580 BOXERS CREEK Essential 2580 BRISBANE GROVE Essential 2580 BUNGONIA Essential 2580 CARRICK Essential 2580 CHATSBURY Essential 2580 CURRAWANG Essential 2580 CURRAWEELA Essential 2580 GOLSPIE Essential 2580 GOULBURN Essential 2580 GREENWICH PARK Essential 2580 GUNDARY Essential 2580 JERRONG Essential 2580 KINGSDALE Essential 2580 LAKE BATHURST Essential 2580 LOWER BORO Essential 2580 MAYFIELD Essential 2580 MIDDLE ARM Essential 2580 MOUNT FAIRY Essential 2580 MOUNT WERONG Essential 2580 MUMMEL Essential 2580 MYRTLEVILLE Essential 2580 OALLEN Essential 2580 PALING YARDS Essential 2580 PARKESBOURNE Essential 2580 POMEROY Essential ©2021 ACN Inc. All rights reserved ACN Pacific Pty Ltd ABN 85 108 535 708 www.acn.com PF-1271 13.05.2021 Page 1 of 31 Sumo has landed in Regional NSW! May 2021 2580 QUIALIGO Essential 2580 RICHLANDS Essential 2580 ROSLYN Essential 2580 RUN-O-WATERS Essential 2580 STONEQUARRY Essential 2580 TARAGO Essential 2580 TARALGA Essential 2580 TARLO Essential 2580 TIRRANNAVILLE Essential 2580 TOWRANG Essential 2580 WAYO Essential 2580 WIARBOROUGH Essential 2580 WINDELLAMA Essential 2580 WOLLOGORANG Essential 2580 WOMBEYAN CAVES Essential 2580 WOODHOUSELEE Essential 2580 YALBRAITH Essential 2580 YARRA Essential 2581 BELLMOUNT FOREST Essential 2581 BEVENDALE Essential 2581 BIALA Essential 2581 BLAKNEY CREEK Essential 2581 BREADALBANE Essential 2581 BROADWAY Essential 2581 COLLECTOR Essential 2581 CULLERIN Essential 2581 DALTON Essential 2581 GUNNING Essential 2581 GURRUNDAH Essential 2581 LADE VALE Essential 2581 LAKE GEORGE Essential 2581 LERIDA Essential 2581 MERRILL Essential 2581 OOLONG Essential ©2021 ACN Inc. -

Government Gazette No 78 of 23 September 2016

Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales Number 78 Friday, 23 September 2016 The New South Wales Government Gazette is the permanent public record of official notices issued by the New South Wales Government. It also contains local council and other notices and private advertisements. The Gazette is compiled by the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office and published on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) under the authority of the NSW Government. The website contains a permanent archive of past Gazettes. To submit a notice for gazettal – see Gazette Information. 2624 NSW Government Gazette No 78 of 23 September 2016 Parliament PARLIAMENT ACTS OF PARLIAMENT ASSENTED TO Legislative Assembly Office, Sydney 21 September 2016 It is hereby notified, for general information, that His Excellency the Lieutenant-Governor, has, in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty, this day assented to the under mentioned Acts passed by the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council of New South Wales in Parliament assembled, viz.: Act No 39 — An Act to amend the Fines Act 1996 with respect to electronic penalty notices; and for other purposes. [Fines Amendment (Electronic Penalty Notices) Bill] Act No 40 — An Act to amend the Security Industry Act 1997 to provide for private investigators to be licensed under that Act and to make consequential amendments to the Commercial Agents and Private Inquiry Agents Act 2004 and other Acts. [Security Industry Amendment (Private Investigators) Bill] Act No 41 — An Act to amend the Rural Fires Act 1997 to provide a system for establishing, maintaining and protecting fire trails on public land and private land; and for other purposes. -

Woodlawn Bioreactor Complaints Register

Woodlawn Bioreactor Complaints Register Date Time EPL Method Type Response Location Description Response/action taken to resolve the complaint 29/08/2021 9:30:00 pm 11436 EPA Environmental Line Odour Letter Tarago The EPA received calls to its Environment Line from residents in Based on the complainant's information, an assessment of the Tarago area who are complaining about an odour. They have meteorological data and operational activity has been generally described the odour as being offensive with a strong completed in order to investigate the potential source or sulphur-like, rotting garbage smell, and gassy. cause of odour. 29/08/2021 10:34:00 am 11436 Community Feedback Odour Letter Mount Fairy Road, Mount Fairy The complainant contacted the community feedback line to Site management explained Veolia’s commitment to seeking Line report that odour was evident when they went outside that out new and innovative ways of reducing odours generated at morning. the site. Based on the complainant's information, an assessment of meteorological data and operational activity has been completed in order to investigate the potential source or cause of odour. 25/08/2021 8:00:00 pm 11436 EPA Environmental Line Odour Letter Lake Bathurst The EPA received calls to its Environment Line from residents in Based on the complainant's information, an assessment of the Tarago area who are complaining about an odour. They have meteorological data and operational activity has been generally described the odour as being offensive with a strong completed in order to investigate the potential source or sulphur-like, rotting garbage smell, and gassy. -

Seasonal Buyer's Guide

Seasonal Buyer’s Guide. Appendix New South Wales Suburb table - May 2017 Westpac, National suburb level appendix Copyright Notice Copyright © 2017CoreLogic Ownership of copyright We own the copyright in: (a) this Report; and (b) the material in this Report Copyright licence We grant to you a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, revocable licence to: (a) download this Report from the website on a computer or mobile device via a web browser; (b) copy and store this Report for your own use; and (c) print pages from this Report for your own use. We do not grant you any other rights in relation to this Report or the material on this website. In other words, all other rights are reserved. For the avoidance of doubt, you must not adapt, edit, change, transform, publish, republish, distribute, redistribute, broadcast, rebroadcast, or show or play in public this website or the material on this website (in any form or media) without our prior written permission. Permissions You may request permission to use the copyright materials in this Report by writing to the Company Secretary, Level 21, 2 Market Street, Sydney, NSW 2000. Enforcement of copyright We take the protection of our copyright very seriously. If we discover that you have used our copyright materials in contravention of the licence above, we may bring legal proceedings against you, seeking monetary damages and/or an injunction to stop you using those materials. You could also be ordered to pay legal costs. If you become aware of any use of our copyright materials that contravenes or may contravene the licence above, please report this in writing to the Company Secretary, Level 21, 2 Market Street, Sydney NSW 2000. -

September 2008 CIRCULATION: 1083

September 2008 CIRCULATION: 1083 All proceeds from advertisements after printing costs go to the WAMBOIN COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION, which started the Whisper in 1981 and continues to own it. This Newsletter is distributed to all RMBs in Wamboin, Bywong, Clare, and Yalana at the beginning of each month, except February. Editor is Ned Noel, 17 Reedy Creek Place, Wamboin, 2620, phone 6238-3484. Contributions which readers may wish to make will be appreciated, and should be submitted by email to [email protected] UT or dropped into his mailbox at 17 Reedy Creek Place. The deadline for the next issue is always the last Sunday of the month, 7 pm, so for the October 2008 Whisper the deadline is Sunday, September 28, 2008, 7:00 pm. The Whisper always goes to deliverers by the following Saturday, which 6 times out of 7 is the first Saturday of the new month. LIFE THREATENING EMERGENCIES Fire/Police/Ambulance - Dial 000 All Hours Queanbeyan Police 6298-0599 Wamboin Fire Brigade Info Centre 6238-3396 Ambulance Bookings 131233 WAMBOIN FACILITIES AND CONTACTS Wamboin Community Assn Helen Montesin President 6238-3208 Bywong Community Assn Nora Stewart Acting President 6230-3305 or www.bywongcommunity.org.au Fire Brigade Cliff Spong Captain 040-999-1340 bh 6236 9220 ah Wamboin Playgroup Angie Matsinas Convener 6238 0334 Sutton School Playgroup Laura Taylor Converner 62369662 Landcare Roger Good President 6236-9048 Community Nurse Heather Morrison Bungendore 6238-1333 Breastfeeding Assoc. Belinda Dennis Community Educator 6236 9979 Emergency Services -

Attachments of Planning and Strategy Committee of the Whole

Planning and Strategy Committee of the Whole 8 May 2019 UNDER SEPARATE COVER ATTACHMENTS QUEANBEYAN-PALERANG REGIONAL COUNCIL PLANNING AND STRATEGY COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE ATTACHMENTS – 8 May 2019 Page i Item 5.1 Development Application - DA.2018.192 - Recreation Facility (Outdoor) Rifle Range - 2155 Collector Road, Currawang Attachment 1 DA.2018.192 - 2155 Collector Road, Currawang - 4.15 Assessment Report ................................................................... 1 Attachment 2 DA.2018.192 - 2155 Collector Road, Currawang - Plans ........ 14 Attachment 4 DA.2018.192 - 2155 Collector Road, Currawang - Draft Conditions ............................................................................... 18 Item 5.3 Planning Proposal - Exempt and Complying Development in the Landuse Zones E4 Environmental Living, RU5 Village and RU1 Primary Production Attachment 1 Report and Planning Proposal - 10 March 2015 ...................... 37 Attachment 2 Gateway Determination - 4 May 2015 ..................................... 57 Attachment 3 Letter to Department of Planning and Environment - 9 September 2015 ..................................................................... 61 Attachment 4 Gateway Determination - Extension - 7 March 2016 ............... 68 Attachment 5 Gateway Determination - Extension - 1 May 2017 .................. 71 Item 5.4 Draft Voluntary Planning Agreement - 18 Mecca Lane, Bungendore Attachment 1 Excerpt from Council Report - Voluntary Planning Agreement - 18 Mecca Lane - 26 March 2016 ......................................... -

Turbine Fact Sheet

Turbine Delivery Fact Sheet Version II - March 2020 Biala Wind Farm is a 31 turbine wind farm currently under construction 14.5km south west of Crookwell in the Southern Tablelands of NSW. It is located 6km south of Grabben Gullen on Grabben Gullen Road. Biala Wind Farm is expected to have a capacity of approximately 110MW, producing enough electricity for around 46,000 typical homes on an average day of wind. We will soon begin transporting the wind turbine components from Port Kembla near Wollongong to the wind farm site. The delivery route is approximately 233km from Port Kembla to Biala Wind Farm. There will be approximately 350 components delivered over a five to six-month period using specialist trucks. We are currently making the final arrangements with Roads and Maritime Services, the Upper Lachlan Shire Council and NSW Police who will escort the larger deliveries. We expect deliveries to commence in Mid-March 2020 with each delivery leaving Port Kembla in the early morning, scheduled to arrive in Goulburn by 5.30am. Delays to road users may be experienced between Goulburn and the wind farm whilst the components are being transported. Between 6am and 9am deliveries are scheduled to travel along the Hume Highway Southern Interchange through Goulburn, north along Crookwell-Goulburn Road and will then bypass Crookwell town centre to travel along Grange Rd, Cullen St, Kialla Rd, and Range Rd connecting to Grabben Gullen Rd before arriving at site. The timeframe is subject to change depending on final arrangements and local conditions on the day. Please check the map for more detail on the route. -

UPPER LACHLAN SHIRE HERITAGE STUDY Final Revised 2010

CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................. 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 11 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 11 Upper Lachlan Local Environmental Plan 2010 – Schedule 5, Environmental Heritage. 14 Upper Lachlan Shire ~ Heritage Assessment .......................................................................... 14 Heritage in New South Wales ..................................................................................................... 15 Legislation and Heritage Registers ............................................................................................. 15 Assessing Heritage Significance .................................................................................................. 16 Listing on the NSW State Heritage Register ............................................................................ 16 Local Heritage Listing .................................................................................................................. 16 The Natural Environment ........................................................................................................... 17 The Built Environment ............................................................................................................... -

Towards 2040 Queanbeyan-Palerang Regional Council Local Strategic Planning Statement | July 2020 Queanbeyan-Palerang Regional Council

TOWARDS 2040 QUEANBEYAN-PALERANG REGIONAL COUNCIL LOCAL STRATEGIC PLANNING STATEMENT | JULY 2020 QUEANBEYAN-PALERANG REGIONAL COUNCIL ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF COUNTRY We pay our respect to the Traditional Custodians of the Queanbeyan-Palerang area, the Ngunnawal and the Walbunja peoples on whose land we live and work. We acknowledge that these lands are Aboriginal lands and pay our respect and celebrate their ongoing cultural traditions and contributions to our surrounding region. We also acknowledge the many other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from across Australia who have now made this area their home, and we pay respect and celebrate their cultures, diversity and contributions to the Queanbeyan-Palerang area and surrounding region. TOWARDS 2040 LOCAL STRATEGIC PLANNING STATEMENT CONTENTS Message from the Mayor and CEO ������������������������������������ iii 3.10 Relationship with the ACT 17 01 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������� iv 3.11 Relationship with the Region – Canberra Region Joint Organisation 17 1.1 What is a Local Strategic Planning Statement (LSPS)? 1 1.2 Requirement for Local Strategic Planning Statements 1 04 Planning Priorities for Queanbeyan-Palerang �����������18 1.3 Relationship to Community Strategic Plan 2018–2028 4.1 Planning Priority 1 – We build on and strengthen our and the Local Environmental Plan 2 community cultural life and heritage 23 1.4 Document Structure 3 4.2 Planning Priority 2 – We have an active and healthy lifestyle 23 4.3 Planning Priority -

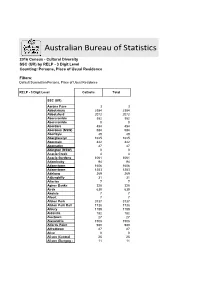

Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census - Cultural Diversity SSC (UR) by RELP - 3 Digit Level Counting: Persons, Place of Usual Residence Filters: Default Summation Persons, Place of Usual Residence RELP - 3 Digit Level Catholic Total SSC (UR) Aarons Pass 3 3 Abbotsbury 2384 2384 Abbotsford 2072 2072 Abercrombie 382 382 Abercrombie 0 0 Aberdare 454 454 Aberdeen (NSW) 584 584 Aberfoyle 49 49 Aberglasslyn 1625 1625 Abermain 442 442 Abernethy 47 47 Abington (NSW) 0 0 Acacia Creek 4 4 Acacia Gardens 1061 1061 Adaminaby 94 94 Adamstown 1606 1606 Adamstown 1253 1253 Adelong 269 269 Adjungbilly 31 31 Afterlee 7 7 Agnes Banks 328 328 Airds 630 630 Akolele 7 7 Albert 7 7 Albion Park 3737 3737 Albion Park Rail 1738 1738 Albury 1189 1189 Aldavilla 182 182 Alectown 27 27 Alexandria 1508 1508 Alfords Point 990 990 Alfredtown 27 27 Alice 0 0 Alison (Central 25 25 Alison (Dungog - 11 11 Allambie Heights 1970 1970 Allandale (NSW) 20 20 Allawah 971 971 Alleena 3 3 Allgomera 20 20 Allworth 35 35 Allynbrook 5 5 Alma Park 5 5 Alpine 30 30 Alstonvale 116 116 Alstonville 1177 1177 Alumy Creek 24 24 Amaroo (NSW) 15 15 Ambarvale 2105 2105 Amosfield 7 7 Anabranch North 0 0 Anabranch South 7 7 Anambah 4 4 Ando 17 17 Anembo 18 18 Angledale 30 30 Angledool 20 20 Anglers Reach 17 17 Angourie 42 42 Anna Bay 789 789 Annandale (NSW) 1976 1976 Annangrove 541 541 Appin (NSW) 841 841 Apple Tree Flat 11 11 Appleby 16 16 Appletree Flat 0 0 Apsley (NSW) 14 14 Arable 0 0 Arakoon 87 87 Araluen (NSW) 38 38 Aratula (NSW) 0 0 Arcadia (NSW) 403 403 Arcadia Vale 271 271 Ardglen -

Graeme Barrow This Book Was Published by ANU Press Between 1965–1991

Graeme Barrow This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. Canberra region car tours Graeme Barrow PL£A*£ RETURN TO Australian National University Press Canberra, Australia, London, England and Miami, Fla., USA, 1981 First published in Australia 1981 Australian National University Press, Canberra © Text and photographs, Graeme Barrow 1981 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Barrow, Graeme: Canberra region car tours. ISBN 0 7081 1087 8. 1. Historic buildings — Australian Capital Territory — Guide-books. I. Title. 919.47’0463 Library of Congress No. 80-65767 United Kingdom, Europe, Middle East, and Africa: Books Australia, 3 Henrietta St., London WC2E 8LU, England North America: Books Australia, Miami, Fla., USA Southeast Asia: Angus & Robertson (S.E. Asia) Pty Ltd, Singapore Japan: United Publishers Services Ltd, Tokyo Design by ANU Graphic Design Adrian Young Typeset by Australian National University Printed by The Dominion Press, Victoria, Australia To Nora -

THE WINDELLAMA NEWS Windellama Progress Association Hall Lnc

THE WINDELLAMA NEWS Windellama Progress Association Hall lnc. Vol. 21 no. 2 – March 2017 Editorial & Layout: Gayle Stanton & Ros Woods Sec/Treas: Christine Woodcock www.windellama.com.au Published Monthly Hard Copy Distribution 400 - Website : 6,000 average/month Windellama, Oallen, Nerriga, Bungonia, Mayfield, Quialigo, Lake Bathurst, Bungendore & Tarago Windellama Hall & Grounds 8th April 2017 (Cnr Windellama and Oallen Ford Roads) DAY STARTS 7.00 AM AUCTION ITEMS booked in by 9.00 AM AUCTION COMMENCES 10.00 AM The Auction is supported by GRAEME WELSH REAL ESTATE & NICK HARTON - LIVESTOCK MANAGER BRAIDWOOD - RAY WHITE REAL ESTATE ITEMS FOR AUCTION may be donated to the Brigade ITEMS sold for more then $10 will attract a 10% service commission donated to the Brigade ITEMS sold for $1000 or more will attract a 8% service commission donated to the Brigade ITEMS sold for $10 or less are donated to the Brigade ITEMS having a reserve price will attract a $5 booking fee per lot * * I M P O R T A N T * * - C A S H & C H E Q U E O N L Y Items for auction are requested to be booked in as soon as possible to assist with advertising in the local paper, eg machinery, antiques, vehicles, building materials. No later than 30 th March HOT & COLD REFRESHMENTS - BBQ STALLS RAFFLES - BAR SERVICE FURTHER INFORMATION Rex Hockey 4844 5147 - Lynton Roberts 0427 445 118 Ellen Sylvester 4844 5407(stalls). With usually over 1,000 people attending. Limited stall sites are available for enquiries contact Ellen 4844 5407.