The Virtual Guru and Beyond: the Changing Role of Teacher in North Indian Classical Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

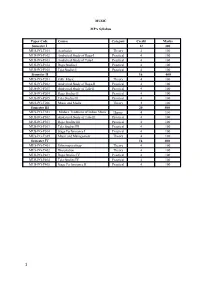

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

The Role of Radio in Promoting the Folk and Sufiana Music in the Kashmir Valley

Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education Vol. XII, Issue No. 23, October-2016, ISSN 2230-7540 The Role of Radio in Promoting the Folk and Sufiana Music in the Kashmir Valley Afshana Shafi* Research Scholar, M.D.U., Rohtak, Haryana Abstract – In this Research work the Researcher reveals the role of All India Radio Srinagar in promoting the folk and sufiana music of Kashmir. Sufiana music is also known as the classical music of Kashmir. There was a time when the radio was considered to be a kind of entertainment only. At that sphere of time, All India Radio Kashmir was also touching the sky from its potential. Radio was widely heard among masses. Radio plays a significant role in the promoting of kashmiri music and the musicians of Kashmir. In this research work the researcher has written about role of Radio in Kashmiri music and in the success of kashmiri musicians. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - As you have heard very different stories about Kashmir evening, in this way Radio Kashmir has been a major yet, but apart from it, Kashmir is full of colors‘. So, let‘s contributor to promoting folk music of Kashmir. talk about those same colors of Kashmir. Kashmiri Music has created a name throughout the world, yes I As the people of Kashmir, living in remote areas, do am talking about sufiana music but before that we will not have access the other source of information and talk about the folk music of Kashmir. The chief source of entertainment, apart from the limited local traditional entertainment is only Music, and an important element activities, for the majority of the people,but as its said governing popularity or unpopularity of the service change is the law of nature but inspite of this radio ―points out H.R Luthra . -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Harmonic Progressions of Hindi Film Songs Based on North Indian Ragas

UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA HARMONIC PROGRESSIONS OF HINDI FILM SONGS BASED ON NORTH INDIAN RAGAS WAJJAKKARA KANKANAMALAGE RUWIN RANGEETH DIAS FEM 2015 40 HARMONIC PROGRESSIONS OF HINDI FILM SONGS BASED ON NORTH INDIAN RAGAS UPM By WAJJAKKARA KANKANAMALAGE RUWIN RANGEETH DIAS COPYRIGHT Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, © in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 All material contained within the thesis, including without limitation text, logos, icons, photographs and all other artwork, is copyright material of Universiti Putra Malaysia unless otherwise stated. Use may be made of any material contained within the thesis for non-commercial purposes from the copyright holder. Commercial use of material may only be made with the express, prior, written permission of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Copyright © Universiti Putra Malaysia UPM COPYRIGHT © Abstract of thesis presented of the Senate of Universiti Putra Malaysia in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy HARMONIC PROGRESSIONS OF HINDI FILM SONGS BASED ON NORTH INDIAN RAGAS By WAJJAKKARA KANKANAMALAGE RUWIN RANGEETH DIAS December 2015 Chair: Gisa Jähnichen, PhD Faculty: Human Ecology UPM Hindi film music directors have been composing raga based Hindi film songs applying harmonic progressions as experienced through various contacts with western music. This beginning of hybridization reached different levels in the past nine decades in which Hindi films were produced. Early Hindi film music used mostly musical genres of urban theatre traditions due to the fact that many musicians and music directors came to the early film music industry from urban theatre companies. -

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

The Melodic Power of Thumri by : INVC Team Published on : 16 Sep, 2018 05:32 AM IST

The melodic power of thumri By : INVC Team Published On : 16 Sep, 2018 05:32 AM IST INVC NEWS New Delhi , Delhi government’s Sahitya Kala Parishad kick started their eighth edition of Thumri Festival- a celebration of light classical music, on 14th September 2018 (Friday) at Kamani Auditorium. The 3 day musical event was inaugurated by the chief guest Sh. Rajendra Pal Gautam, Hon’ble Minister for Social Welfare, Govt. Of NCT of Delhi. The evening began with the performance of critically acclaimed Indian classical singer Padmaja Chakraborty, who sang Khamaj Thumri in Jat taal, Tappa in Raga Kafi and Kajri in Raag Mishra Pilu in Keherwa taal. The second performance was by the renowned vocalist and doyen of Kirana Gharana - Sri Jayateerth Mevundi. The classical singer, known for the ease and felicity of his singing style, mesmerized the audience with Raag Tilang Thumri, kafi Thumri, Jogiya Thumri, and Raag Pahadi in different raag and tal. The evening was culminated with a power packed performance by Shubha Mudgal who performed on Bol Banau Thumri and Bandish ki Thumri in which she sang rare types of Thumri for the audience. This musical fare is designed to showcase veteran Thumri singers along with the upcoming young talents who will share the space and light up the evening with their performances. About thumri : Thumri is a beautiful blend of Hindustani classical music with traits of folk literature. Thumri holds a history of over 500 years in Hindustani Classical music. Thumri used to be sung in the royal kingdoms and palaces and its background originates from Varanasi, Gwalior and Awadh were they used to be Thumri vocalists in the royal courts. -

A History of Indian Music by the Same Author

68253 > OUP 880 5-8-74 10,000 . OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No.' poa U Accession No. Author'P OU H Title H; This bookok should bHeturned on or befoAbefoifc the marked * ^^k^t' below, nfro . ] A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC BY THE SAME AUTHOR On Music : 1. Historical Development of Indian Music (Awarded the Rabindra Prize in 1960). 2. Bharatiya Sangiter Itihasa (Sanglta O Samskriti), Vols. I & II. (Awarded the Stisir Memorial Prize In 1958). 3. Raga O Rupa (Melody and Form), Vols. I & II. 4. Dhrupada-mala (with Notations). 5. Sangite Rabindranath. 6. Sangita-sarasamgraha by Ghanashyama Narahari (edited). 7. Historical Study of Indian Music ( ....in the press). On Philosophy : 1. Philosophy of Progress and Perfection. (A Comparative Study) 2. Philosophy of the World and the Absolute. 3. Abhedananda-darshana. 4. Tirtharenu. Other Books : 1. Mana O Manusha. 2. Sri Durga (An Iconographical Study). 3. Christ the Saviour. u PQ O o VM o Si < |o l "" c 13 o U 'ij 15 1 I "S S 4-> > >-J 3 'C (J o I A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC' b SWAMI PRAJNANANANDA VOLUME ONE ( Ancient Period ) RAMAKRISHNA VEDANTA MATH CALCUTTA : INDIA. Published by Swaxni Adytaanda Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta-6. First Published in May, 1963 All Rights Reserved by Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta. Printed by Benoy Ratan Sinha at Bharati Printing Works, 141, Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-6. Plates printed by Messrs. Bengal Autotype Co. Private Ltd. Cornwallis Street, Calcutta. DEDICATED TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND HIS SPIRITUAL BROTHER SWAMI ABHEDANANDA PREFACE Before attempting to write an elaborate history of Indian Music, I had a mind to write a concise one for the students. -

Ragang Based Raga Identification System

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 16, Issue 3 (Sep. - Oct. 2013), PP 83-85 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Ragang based Raga Identification system Awadhesh Pratap Singh Tomer Assistant Professor (Music-vocal), Department of Music Dr. H. S. G. Central University Sagar M.P. Gopal Sangeet Mahavidhyalaya Mahaveer Chowk Bina Distt. Sagar (M.P.) 470113 Abstract: The paper describes the importance of Ragang in the Raga classification system and its utility as being unique musical patterns; in raga identification. The idea behind the paper is to reinvestigate Ragang with a prospective to use it in digital classification and identification system. Previous works in this field are based on Swara sequence and patterns, Pakad and basic structure of Raga individually. To my best knowledge previous works doesn’t deal with the Ragang Patterns for identification and thus the paper approaches Raga identification with a Ragang (musical pattern group) base model. This work also reviews the Thaat-Raagang classification system. This describes scope in application for Automatic digital teaching of classical music by software program to analyze music (Classical vocal and instrumental). The Raag classification should be flawless and logically perfect for best ever results. Key words: Aadhar shadaj, Ati Komal Gandhar , Bahar, Bhairav, Dhanashri, Dhaivat, Gamak, Gandhar, Gitkarri, Graam, Jati Gayan, Kafi, Kanada, Kann, Komal Rishabh , Madhyam, Malhar, Meed, Nishad, Raga, Ragang, Ragini, Rishabh, Saarang, Saptak, Shruti, Shrutiantra, Swaras, Swar Prastar, Thaat, Tivra swar, UpRag, Vikrat Swar A Raga is a tonal frame work for composition and improvisation. It embodies a unique musical idea.(Balle and Joshi 2009, 1) Ragang is included in 10 point Raga classification of Saarang Dev, With Graam Raga, UpRaga and more. -

Formulas and the Building Blocks of Ṭhumrī Style—A Study in “Improvised” Music

Formulas and the Building Blocks of Ṭhumrī Style—A Study in “Improvised” Music Chloe Zadeh PART I: IMPROVISATION, STRUCTURE AND FORMULAS IN NORTH INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC usicians, musicologists and teenage backpackers alike speak of “improvisation” in M modern-day Indian classical music.1 Musicians use the term to draw attention to differences between different portions of a performance, distinguishing between the “composition” of a particular performance (in vocal music, a short melody, setting a couple of lines of lyrics) and the rest of the performance, which involves musical material that is different in each performance and that musicians often claim to have made up on the spur of the moment.2 In their article “Improvisation in Iranian and Indian music,” Richard Widdess and Laudan Nooshin draw attention to modern-day Indian terminology which reflects a conceptual distinction between improvised and pre-composed sections of a performance (2006, 2–4). The concept of improvisation has also been central to Western imaginings of North Indian classical music in the twentieth century. John Napier has discussed the long history of Western descriptions of Indian music as “improvised” or “extemporized,” which he dates back to the work of Fox Strangways in 1914. He points out the importance the concept took on, for example, in the way in which Indian music was introduced to mainstream Western audiences in the 1960s; he notes that the belief that the performance of Indian music 1 I am very grateful to Richard Widdess and Peter Manuel for their comments on draft versions of this article. 2 The relationship between those parts of the performance that musicians label the “composition” and the rest of the performance is actually slightly more complicated than this; throughout, a performance of North Indian classical music is normally punctuated by a refrain, or mukhra, which is a part of the composition. -

A) Indian Music (Hindustani) (872

MUSIC Aims: One of the three following syllabuses may be offered: 1. To encourage creative expression in music. 2. To develop the powers of musical appreciation. (A) Indian Music (Hindustani) (872). (B) Indian Music (Carnatic) (873). (C) Western Music (874). (A) INDIAN MUSIC (HINDUSTANI) (872) (May not be taken with Western Music or Carnatic Music) CLASSES XI & XII The Syllabus is divided into three parts: PAPER 2: PRACTICAL (30 Marks) Part 1 (Vocal), The practical work is to be evaluated by the teacher and a Visiting Practical Examiner appointed locally Part 2 (Instrumental) and and approved by the Council. Part 3 (Tabla) EVALUATION: Candidates will be required to offer one of the parts Marks will be distributed as follows: of the syllabus. • Practical Examination: 20 Marks There will be two papers: • Evaluation by Visiting Practical 5 Marks Paper 1: Theory 3 hours ….. 70 marks Examiner: Paper 2: Practical ….. 30 marks. (General impression of total Candidates will be required to appear for both the performance in the Practical papers from one part only. Examination: accuracy of Shruti and Laya, confidence, posture, PAPER 1: THEORY (70 Marks) tonal quality and expression) In the Theory paper candidates will be required to • Evaluation by the Teacher: 5 Marks attempt five questions in all, two questions from Section A (General) and EITHER three questions (of work done by the candidate from Section B (Vocal or Instrumental) OR three during the year). questions from Section C (Tabla). NOTE: Evaluation of Practical Work for Class XI is to be done by the Internal Examiner. 266 CLASS XI PART 1: VOCAL MUSIC PAPER 1: THEORY (70 Marks) The above Ragas with special reference to their notes Thaat, Jaati, Aaroh, Avaroh, Pakad, Vadi, 1. -

New Trends in Hindustani Sitar Music in Malaysia

23 Towards Fusion: New Trends in Hindustani Sitar Music in Malaysia Pravina Manoharan Universiti Sains Malaysia Abstract While a classical Sitar recital in Malaysia still retains many of its original forms and practices, local sitarists are experimenting with new musical ideas to promote the Sitar and its music to a wider audience of mixed ethnicity. Musicians combine Hindustani musical elements such as Raag (melody) and Taal (rhythmic cycle) with different musical elements such as the Chinese pentatonic scale and Arabian Maqam as well as new genres to produce a musical blend broadly dubbed as ‘fusion music’. This article explores how the characteristics of the Hindustani elements of Raag and Taal are adopted to complement the structure and style of the new compositions. Different Sitar playing styles and techniques are employed in the performance of fusion compositions that use Blues or Bossa Nova genres. Keywords: Raag, Taal, fusion, Sitar music. 24 Wacana Seni Journal of Arts Discourse. Jil./Vol.7.2008 Introduction Malaysia is a multiracial and multicultural society that has a rich and diverse cultural and musical heritage. Indians represent the third largest population in the country. The classical music practiced by Malaysian Indians is based on the ancient traditional system that originated in India. Indian classical music refers to both the South Indian Carnatic and North Indian Hindustani systems. Hindustani and Carnatic music share a common ancient musical heritage, as both systems are built upon highly complex and elaborate melodic structures called Raag, and both employ a system of rhythm and meter that falls under the rubric of Taal (rhythmic cycle).