Status and Occurrence of Oriental Turtle-Dove (Streptopelia Orientalis) in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Band-Tailed Pigeon (Patagioenas Fasciata)

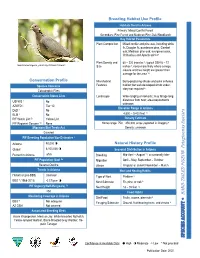

Band-tailed Pigeon (Patagioenas fasciata) NMPIF level: Species Conservation Concern, Level 2 (SC2) NMPIF assessment score: 15 NM stewardship responsibility: Low National PIF status: Watch List New Mexico BCRs: 16, 34, 35 Primary breeding habitat(s): Ponderosa Pine Forest, Mixed Conifer Forest Other habitats used: Spruce-Fir Forest, Madrean Pine-Oak Woodland Summary of Concern Band-tailed Pigeon is a summer resident of montane forests in New Mexico. Both locally and across its wide geographic range the species has shown sharp population declines since the 1960s. Prior to that time, extensive commercial hunting may have significantly reduced the population from historic levels. It is not known if current declines are the result of continuing hunting pressure, habitat changes, or other factors. Associated Species Northern Goshawk, Long-eared Owl, Lewis's Woodpecker (SC1), Acorn Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Olive-sided Flycatcher (BC2), Greater Pewee (BC2), Steller's Jay, Red-faced Warbler (SC1). Distribution A Pacific coast population of Band-tailed Pigeon breeds from central California north to Canada and Alaska, extending south to Baja California in the winter. In the interior, a migratory population breeds in upland areas of southern Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico. The species occurs year-round throughout the highlands of central Mexico, south to Central and South America. In New Mexico, Band-tailed Pigeon breeds in forest habitat throughout the state, west of the plains. It is perhaps most common in the southwest (Parmeter et al. 2002). Ecology and Habitat Requirements In the Southwest, Band-tailed Pigeons inhabit montane forests dominated by pines and oaks, sometimes extending upward in elevation to timberline. -

Two Oriental Turtle-Doves (Streptopelia Orientalis) Reach California Jon L

NOTES TWO ORIENTAL TURTLE-DOVES (STREPTOPELIA ORIENTALIS) REACH CALIFORNIA JON L. DUNN, 52 Nevada Street, Bishop, California 93514; [email protected] KEITH HANSEN, P. O. Box 332, Bolinas, California 94924 The Oriental Turtle-Dove (Streptopelia orientalis), also known as the Rufous Turtle-Dove (e.g., Cramp 1985) or the Eastern Turtle-Dove (Goodwin 1983), is a widespread polytypic Asian species that breeds from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific coast of the Russian Far East, including Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. It also breeds in Japan (south to the Ryukyu Islands) and on Taiwan. It breeds south to west-central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Myanmar, and northern Indochina. In the Russian Far East its breeding range extends east to the Sea of Okhotsk and as far north as 64° N in the Lena River valley (Wilson and Korovin 2003). Although the species is resident in parts of its range, it vacates the entire northern portion of the breeding range (e.g., all of Russia) in the fall (Wilson and Korovin 2003). These migratory birds winter mostly within the range of residency farther south. Over large portions of northern, central, and western China, the species is only a passage migrant (see range map in Wilson and Korovin 2003). We report here on two records from California, both in the late fall and early winter: 29 October 1988 at Furnace Creek Ranch, Death Valley National Park, Inyo County, and 9–31 December 2002 at Bolinas, Marin County (California Bird Records Com- mittee 2007); archived photos and a videotape of the latter bird are stored with the record (2003-036) in the files of the California Bird Records Committee (CBRC) at the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology in Camarillo, California. -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

Pigeon, Band-Tailed

Pigeons and Doves — Family Columbidae 269 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas fasciata California’s only native large pigeon can be seen year round in San Diego’s mountains, sometimes in large flocks, sometimes as only scattered individu- als. Elderberries and acorns are its staple foods, so the Band-tailed Pigeon frequents woodland with abundant oaks. Though it inhabits all the mountains where the black and canyon live oaks are common, its distribution is oddly patchy in foothill woodland dominated by the coast live oak. Both migratory and nomadic, the Band-tailed Pigeon may be common in some areas in some years and absent in others; it shows up occasionally in all regions of the county as Photo by Anthony Mercieca a vagrant. Breeding distribution: As its name in Spanish suggests, ries in dry scrub. Eleanor Beemer noted this movement Palomar Mountain is the center of Band-tailed Pigeon at Pauma Valley in the 1930s, and it continues today. abundance in San Diego County (paloma = pigeon or Some of our larger summer counts, including the largest, dove). The pigeons move up and down the mountain, were in elderberries around the base of Palomar: 35 near descending to the base in summer to feed on elderber- Rincon (F13) 7 July 2000 (M. B. Mosher); 110 in Dameron Valley (C16) 23 June 2001 (K. L. Weaver). Most of the birds nest in the forested area high on the mountain, but some nest around the base, as shown by a fledgling in Pauma Valley (E12) 19 May 2001 (E. C. Hall) and an occupied nest near the West Fork Conservation Camp (E17) 12 May 2001 (J. -

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA CHORDATA 16SCCZO3 Dr. R. JENNI & Dr. R. DHANAPAL DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY M. R. GOVT. ARTS COLLEGE MANNARGUDI CONTENTS CHORDATA COURSE CODE: 16SCCZO3 Block and Unit title Block I (Primitive chordates) 1 Origin of chordates: Introduction and charterers of chordates. Classification of chordates up to order level. 2 Hemichordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Balanoglossus and its affinities. 3 Urochordata: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Herdmania and its affinities. 4 Cephalochordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Branchiostoma (Amphioxus) and its affinities. 5 Cyclostomata (Agnatha) General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Petromyzon and its affinities. Block II (Lower chordates) 6 Fishes: General characters and classification up to order level. Types of scales and fins of fishes, Scoliodon as type study, migration and parental care in fishes. 7 Amphibians: General characters and classification up to order level, Rana tigrina as type study, parental care, neoteny and paedogenesis. 8 Reptilia: General characters and classification up to order level, extinct reptiles. Uromastix as type study. Identification of poisonous and non-poisonous snakes and biting mechanism of snakes. 9 Aves: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Columba (Pigeon) and Characters of Archaeopteryx. Flight adaptations & bird migration. 10 Mammalia: General characters and classification up -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Myanmar

Avibase Page 1of 30 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Myanmar 2 Number of species: 1088 3 Number of endemics: 5 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of introduced species: 1 6 7 8 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Myanmar. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=mm [23/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

India: Kaziranga National Park Extension

INDIA: KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION FEBRUARY 22–27, 2019 The true star of this extension was the Indian One-horned Rhinoceros (Photo M. Valkenburg) LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM INDIA: KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION February 22–27, 2019 By Machiel Valkenburg This wonderful Kaziranga extension was part of our amazing Maharajas’ Express train trip, starting in Mumbai and finishing in Delhi. We flew from Delhi to Guwahati, located in the far northeast of India. A long drive later through the hectic traffic of this enjoyable country, we arrived at our lodge in the evening. (Photo by tour participant Robert Warren) We enjoyed three full days of the wildlife and avifauna spectacles of the famous Kaziranga National Park. This park is one of the last easily accessible places to find the endangered Indian One-horned Rhinoceros together with a healthy population of Asian Elephant and Asiatic Wild Buffalo. We saw plenty individuals of all species; the rhino especially made an impression on all of us. It is such an impressive piece of evolution, a serious armored “tank”! On two mornings we loved the elephant rides provided by the park; on the back of these attractive animals we came very close to the rhinos. The fertile flood plains of the park consist of alluvial silts, exposed sandbars, and riverine flood-formed lakes called Beels. This open habitat is not only good for mammals but definitely a true gem for some great birds. Interesting but common birds included Bar-headed Goose, Red Junglefowl, Woolly-necked Stork, and Lesser Adjutant, while the endangered Greater Adjutant and Black-necked Stork were good hits in the stork section. -

Migratory Birds of Ladakh a Brief Long Distance Continental Migration

WORLD'S MIGRATORY BIRDS DAY 08 MAY, 2021 B R O W N H E A D E D G U L L MIGRATORY BIRDS OF LADAKH A BRIEF LONG DISTANCE CONTINENTAL MIGRATION the Arctic Ocean and the Indian Ocean, and comprises several migration routes of waterbirds. It also touches “West Asian- East African Flyway”. Presence of number of high-altitude wetlands (>2500 m amsl altitude) with thin human population makes Ladakh a suitable habitat for migration and breeding of continental birds, including wetlands of very big size (e.g., Pangong Tso, Tso Moriri, Tso Kar, etc.). C O M M O N S A N D P I P E R Ladakh provides a vast habitat for the water birds through its complex Ladakh landscape has significance network of wetlands including two being located at the conjunction of most important wetlands (Tso Moriri, four zoogeographic zones of the world Tso Kar) which have been designated (Palearctic, Oriental, Sino-Japanese and as Ramsar sites. Sahara-Arabian). In India, Ladakh landscape falls in Trans-Himalayan Nearly 89 bird species (long distance biogeographic zone and two provinces migrants) either breed or roost in (Ladakh Mountains, 1A) and (Tibetan Ladakh, and most of them (59) are Plateau, 1B). “Summer Migrants”, those have their breeding grounds here. Trans-Himalayan Ladakh is an integral part of the "Central Asian Flyway" of migratory birds which a large part of the globe (Asia and Europe) between Ladakh also hosts 25 bird species, during their migration along the Central Asian Flyway, as “Passage Migrants” which roost in the region. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Band-Tailed Pigeon, Photo by ©Robert Shantz Size Inches 8; Nests More Likely Where Canopy Closure and Tree Height Are Greater Than Average for the Area 10

Breeding Habitat Use Profile Habitats Used in Arizona Primary: Mixed Conifer Forest Secondary: Pine Forest and Madrean Pine-Oak Woodlands Key Habitat Parameters Plant Composition Mixed conifer and pine-oak, including white fir, Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, Gambel oak; Madrean pine-oak: evergreen oaks, Chihuahua and Apache pines8 Plant Density and 60 – 200 trees/ac 9; typical DBH 6 – 12 Band-tailed Pigeon, photo by ©Robert Shantz Size inches 8; nests more likely where canopy closure and tree height are greater than average for the area 10 Conservation Profile Microhabitat Berry-producing shrubs and oaks enhance Species Concerns Features habitat; but well-developed shrub under- story not required 8 Catastrophic Fires Conservation Status Lists Landscape Wide-ranging or nomadic; may forage long distances from nest; area requirements USFWS 1 No unknown AZGFD 2 Tier 1C Elevation Range in Arizona 3 DoD No 11 BLM 4 No 4,800 – 9,400 feet PIF Watch List 5b Yellow List Density Estimate PIF Regional Concern 5a None Home range: 750 – 450,000 acres (reported in Oregon) 8 Migratory Bird Treaty Act Density: unknown Covered PIF Breeding Population Size Estimates 6 Arizona 40,000 ◑ Natural History Profile Global 6,100,000 ◑ Seasonal Distribution in Arizona Percent in Arizona .65% Breeding Mid-April – August 11; occasionally later PIF Population Goal 5b Migration April – May; September – October Reverse Decline Winter Irregular or absent November – March Trends in Arizona Nest and Nesting Habits Historical (pre-BBS) Unknown 8 Type of Nest Platform 7 BBS -

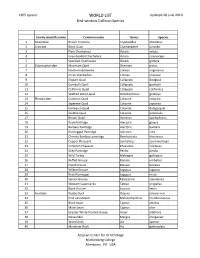

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38