Downloaded From: Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan DOI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISSN 1820-4589 the CULTURE of POLIS, Vol. XVII (2020)

ISSN 1820-4589 THE CULTURE OF POLIS, vol. XVII (2020), special edition a journal for nurturing democratic political culture THE CULTURE OF POLIS a journal for nurturing democratic political culture Publishers: Culture – Polis Novi Sad, www.kpolisa.com; Institute of European studies Belgrade, www.ies.rs Editorial board: dr Srbobran Branković, dr Mirko Miletić, dr Aleksandar M. Petrović, dr Slaviša Orlović, dr Veljko Delibašić, dr Đorđe Stojanović, dr Milan Subotić, dr Aleksandar Gajić, dr Nebojša Petrović, dr Darko Gavrilović, dr Miloš Savin, dr Aleksandra Šuvaković, dr Milan Igrutinović. Main and accountable editor: dr Ljubiša Despotović Deputy of the main and accountable editor: dr Zoran Jevtović Assistant of the main and accountable editor: dr Željko Bjelajac Secretary of the editorial board: dr Aleksandar Matković Foreign members of the editorial board: dr Vasilis Petsinis (Grčka), dr Pol Mojzes (SAD), dr Pavel Bojko (Ruska Federacija), dr Marko Atila Hoare (Velika Britanija), dr Tatjana Tapavički - Duronjić (RS-BiH), dr Davor Pauković (Hrvatska), dr Eugen Strautiu (Rumunija) dr Daniela Blaževska (Severna Makedonija) dr Dejan Mihailović (Meksiko) Text editor: Milan Karanović Journal council: dr Živojin Đurić, predsednik; dr Vukašin Pavlović, dr Ilija Vujačić, dr Srđan Šljukić, dr Dragan Lakićević, dr Jelisaveta Todorović, dr Radoslav Gaćinović, dr Zoran Aracki, dr Nedeljko Prdić, dr Zoran Avramović, dr Srđan Milašinović, dr Joko Dragojlović, dr Marija Đorić, dr Boro Merdović, dr Aleksandar M. Filipović, dr Goran Ivančević. Printing: NS Mala knjiga + Circulation: 400. UDC 316.334.56:008 CIP – Cataloging in publication Library of Matica srpska, Novi Sad 3 КУЛТУРА полиса : часопис за неговање демократске политичке културе / главни и одговорни уредник Љубиша Деспотовић. -

Bdsm, Kink, and Consent: What the Law Can Learn from Consent-Driven Communities

BDSM, KINK, AND CONSENT: WHAT THE LAW CAN LEARN FROM CONSENT-DRIVEN COMMUNITIES Mika Galilee-Belfer* Millions of Americans participate in consensual, mutually agreed-upon activities such as bondage, dominance, and submission—collectively referred to as BDSM or kink—yet the relationship between individual consent to such participation and consent as legally understood and defined is imperfect at best. Because the law has not proven adept at adjudicating disputes that arise in BDSM situations, communities that practice BDSM have adopted self-policing mechanisms (formal and informal) aimed at replicating and even advancing the goals and protections of conventional law enforcement. This self-policing is particularly important because many jurisdictions hold there can be no consent to the kind of experiences often associated with BDSM; this is true in practice irrespective of the existence of statutory language regarding consent. In this Note, I compare legal communities and BDSM communities across three variables: how consent is defined, how violations are comparably adjudicated, and the types of remedies available by domain. In the process, I examine what norm-setting and rule adjudication look like when alternative communities choose to define, and then operate within, norms and controls that must be extra-legal by both necessity and design. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 508 I. CURRENT ISSUES AT THE INTERSECTION OF BDSM AND THE LAW .................. -

The “Jūdō Sukebei”

ISSN 2029-8587 PROBLEMS OF PSYCHOLOGY IN THE 21st CENTURY Vol. 9, No. 2, 2015 85 THE “JŪDŌ SUKEBEI” PHENOMENON: WHEN CROSSING THE LINE MERITS MORE THAN SHIDŌ [MINOR INFRINGEMENT] ― SEXUAL HARASSMENT AND INAPPROPRIATE BEHAVIOR IN JŪDŌ COACHES AND INSTRUCTORS Carl De Crée University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium International Association of Judo Researchers, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The sport of jūdō was intended as an activity “for all”. Since in 1996 a major sex abuse scandal broke out that involved a Dutch top jūdō coach and several female elite athletes, international media have identified many more abuses. To date no scholarly studies exist that have examined the nature, extent, and consequences of these anomalies. We intend in this paper to review and analyze sexual abuses in jūdō. To do so we offer a descriptive jurisprudence overview of relevant court and disciplinary cases, followed by a qualitative-analytical approach looking at the potential factors that prompt jūdō-related bullying and sexual harassment. Sex offenders may be attracted to jūdō because of: 1. the extensive bodily contact during grappling, 2. the easy access to voyeuristic opportunities during contest weigh-ins and showering, 3. Jūdō’s authoritarian and hierarchical structure as basis for ‘grooming’, 4. lack of integration of jūdō’s core moral component in contemporary jūdō coach and instructor education, and 5. its increasing eroti- cization by elite jūdō athletes posing for nude calendars and media and by specialized pornographic jūdō manga and movies. Cultural conceptions and jurisprudence are factors that affect how people perceive the seriousness and how these offences are dealt with. -

BDSM Checklist

BDSM Desires/Limitations List Below you will find a list of different BDSM activities. Take the time to go through this list and figure out where your desires lie. Also make sure you indicate where your soft limits and hard limits are. The time spent on this sheet can help to provide you with better clarification of what you need and desire in your life. It can also give a partner a reference to better understand your desires and what is on and off limits for play. Instructions: On the left hand side is each BDSM/Kinky/Fetish Activity to the right of each activity are four columns. Previous Experience: Here is your chance to list how much experience you have with the particular activity. If you have no experience you can leave the space blank for that activity. If you have experience you can list your level of experience from 1 – 10 1 – having only tried the activity one or two times 2-4 – Increasing the amount of play with that activity 5 – a moderate amount of experience or on and off experience in past training/play 6-9 - Increasing the amount of play with that activity BDSMTrainingAcademy.com 10 – having participated in the activity more times than you can remember or was a regular activity in past training/play Desire/Limits: In this column you can list the activities that you desire to have incorporated into play/training and also the activities that are off limits and that you don't want to take part in. ?: By putting a question mark beside an activity you are indicating that you do not know what this activity is and therefore can not determine interest or non-interest in the activity. -

AMERICAN INFERNO by PATRICK DENKER

AMERICAN INFERNO by PATRICK DENKER (Under the Direction of Reginald McKnight) ABSTRACT American Inferno, a novel, is a loose transposition of Dante‟s Inferno into a contemporary American setting. Its chapters (or “circles”) correspond to Dante‟s nine circles of Hell: 1) Limbo, 2) Lust, 3) Gluttony, 4) Hoarding & Wasting, 5) Wrath, 6) Heresy, 7) Violence, 8) Fraud and 9) Treachery. The novel‟s Prologue — Circle 0 — corresponds to the events that occur, in the Inferno, prior to Dante‟s and Virgil‟s entrance into Hell proper. The novel is a contemporary American moral inquiry, not a medieval Florentine one: thus it is sometimes in harmony with and sometimes a critique of Dante‟s moral system. Also, like the Inferno, it is not an investigation just of its characters‟ personal moral struggles, but also of the historical sins of its nation: for Dante, the nascent Italian state; for us, the United States. Thus the novel follows the life story of its principal character as he progresses from menial to mortal sins while simultaneously considering American history from America‟s early Puritan foundations in the Northeast (Chapters 1-4) through slavery, civil war and manifest destiny (Chapters 5-7) to its ultimate expression in the high-technology West-Coast entertainment industry (Chapters 8-9). INDEX WORDS: Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Inferno, Sin, American history, American morality, Consumerism, Philosophical fiction, Social realism, Frame narrative, Christianity, Secularism, Enlightenment, Jefferson, Adorno, Culture industry, lobbying, public relations, advertising, marketing AMERICAN INFERNO by PATRICK DENKER B.A., Duke University, 1992 M.F.A., San Francisco State University, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 Patrick Denker All Rights Reserved AMERICAN INFERNO by PATRICK DENKER Major Professor: Reginald McKnight Committee: O. -

ENEGADE IP 'J.JV.JYJ.J, Therip

. .,· .---· , . ..· Protests . , . co.ntinue. \ •' .. ' . ;~..-- · hn1nigrati,,u ,·;·,11~ ai \l!lrtio Lu&hcr .~in~ Park 01, ( ·~,ar Cha\·~, D.t}. ) ... --. l .. · · 1 · News, Page 3 J ' , I . ' • • ot • • I - ·' ENEGADE IP 'J.JV.JYJ.J, therip. com Vol. 78 • No. 5 Bakersfield College Apri! 11, 2007 I Burgl~r • BC students voted for their caught by representatives in the Student Government Association during Spring Fling week lv1arch 26-Ma.cch 30. security By TAYLOR M. GOMBOS tgombo~baJ:.ersfiela'college.edu Rip staff writer • Car burglary suspect appprehended by. campus public Attention students of Bakmfield College: You have a safety officers in the parking lot new leader. John Lopez, BC computer science major, defeated the on M~.rch 21. SGA veteran Alan Crane to win the presidency of me Stu dent Government Association. · . By ~'YLE BEALL Lopez defeated Crane by securi.ag 66% (364 votes) of kbeall@bakersfieldc(}//ege.edu Rip staff \•.triter i.;~ \v.¢:i wailc U.llltc ouly ~-ureo 33.3% (184 votes) of the Votes. Crane said that he was a little swprised by the 66% mar' A burglary suspcc-t was apprehended and ar gin oot added. "'ibe students have spoken and said that the!' rested on the po.rt.ing lot at the northeast side of , 1;llffipo5 three Wllllt John as a president. I am sure he will do a fine job. He for felony count$ of car burglary, including one felooy count of possession of will have the support of a team whlch is absolutely ~ moo burglary qualified exocuti~ team ever put together Ill BC." tools end a felony coont of grand theft Cnne, who cwn:ntly seTYes as .legislatiYc liaison of the auto, SGA aw ~It of the statewide ·suadent senate, lklded The arrest .,.,as made on campus by 8~Ll College public safety officers after IY',..e of the of tb.l.t be is planning 10 go back to being a regular sni&:nt when his Sfll1c term is up in J\D'le. -

Presenter Description Day Time Room Although the TK Is Looked at As a Staple Tie for Shibari, So Many People Find It Unsustainable

Kink Presenter Description Day Time Room Although the TK is looked at as a staple tie for Shibari, so many people find it unsustainable. Whether it be a shoulder injury, a previous nerve injury, circulation issues, etc, etc, the list goes on. The Bird Cage (named because we designed this for groundbird), is an option for rope partners to use for floor work or suspension. While still offering an attractive aesthetic, it proves to be a chest loading "The Bird Cage" - a chest loading option, usable for dynamic suspensions, static, partials, and box tie Rae and groundbird floorwork. All body types and flexibility spectrums welcome. Saturday 1:00 PM Georgia 11 This class teaches tying the 2-rope takatekote. This tie is suitable for use on its own, or as the foundation for the 3-rope Osada-ryu takatekote. The class centers around tying the takatekote, while emphasizing subjective aspects such as tension, distance, finishing, and rhythm. Each top needs a partner and 2 lengths of rope each 25- 2TK: 2-Rope Takatekote RigerousMike 30 feet long. Saturday 11:30 AM Georgia 11 We’ve discussed the basics and we’ve seen how needles can interact with other needles to build sensation. Now it’s time to ask the question: Can needles play well with other toys? Why yes, yes they can. You don’t have to limit your needle scenes to just needles, and you can incorporate needleplay into other types of scenes as well. In this class we’ll explore how to do so safely, as we integrate modalities such as percussion, electricity, chemical irritants, other types of sharps, and much more into our needleplay. -

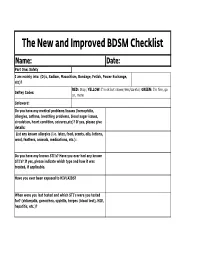

The New and Improved BDSM Checklist

The New and Improved BDSM Checklist Name: Date: Part One: Safety I am mainly into: (D/s, Sadism, Masochism, Bondage, Fetish, Power Exchange, etc)? RED: Stop; YELLOW: I'm ok but slower/less/careful; GREEN: I'm fine, go Saftey Codes: on, more Safeword: Do you have any medical problems/issues (hemophilia, allergies, asthma, breathing problems, blood sugar issues, circulation, heart condition, seizures,etc)? If yes, please give details: List any known allergies (i.e. latex, food, scents, oils, lotions, wool, feathers, animals, medications, etc.): Do you have any known STI's? Have you ever had any known STI's? If yes, please indicate which type and how it was treated, if applicable. Have you ever been exposed to HIV/AIDS? When were you last tested and which STI's were you tested for? (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes (blood test), HIV, hepatitis, etc.)? Have you received any STI vaccinations (i.e. hepatitis A & B or HPV)? How often do you practice safe sex (always, most of the time, some of the time, never)? Please explain reasons for not doing so. Medications: Have you taken any medication, including Asprin within the last 4-6 hours (Asprin changes your blood's clotting time). Please include a list of all prescription and over the counter medications you are currently taking: Visible brusies, cuts, or marks must be avoided (yes or no)? Please list any no hit zones, if any: Do you have any phobias or fears that the Dom/Domme should be aware of (blood, needles, enclosed areas, etc.)? Do you want aftercare (yes, no, only in certain circumstances, unsure, etc.)? Please explain. -

Sexual Harassment and Inappropriate Behavior in Jūdō Coaches and Instructors

ISSN 2029-8587 PROBLEMS OF PSYCHOLOGY IN THE 21st CENTURY Vol. 9, No. 2, 2015 85 The “Jūdō Sukebei” PheNOMENON: When Crossing the Line MeritS MORE THAN Shidō [Minor infringeMent] ― SexuaL harassment and inappropriate behavior in Jūdō CoaCheS and inStruCtorS Carl De Crée university of rome “tor vergata”, rome, italy ghent university, ghent, belgium international association of Judo researchers, united kingdom e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The sport of jūdō was intended as an activity “for all”. Since in 1996 a major sex abuse scandal broke out that involved a Dutch top jūdō coach and several female elite athletes, international media have identified many more abuses. To date no scholarly studies exist that have examined the nature, extent, and consequences of these anomalies. We intend in this paper to review and analyze sexual abuses in jūdō. To do so we offer a descriptive jurisprudence overview of relevant court and disciplinary cases, followed by a qualitative-analytical approach looking at the potential factors that prompt jūdō-related bullying and sexual harassment. Sex offenders may be attracted to jūdō because of: 1. the extensive bodily contact during grappling, 2. the easy access to voyeuristic opportunities during contest weigh-ins and showering, 3. Jūdō’s authoritarian and hierarchical structure as basis for ‘grooming’, 4. lack of integration of jūdō’s core moral component in contemporary jūdō coach and instructor education, and 5. its increasing eroti- cization by elite jūdō athletes posing for nude calendars and media and by specialized pornographic jūdō manga and movies. Cultural conceptions and jurisprudence are factors that affect how people perceive the seriousness and how these offences are dealt with. -

City Research Online

Cannon-Gibbs, S. (2016). The dichotomy of ‘them and us’ thinking in Counselling Psychology incorporating an empirical study on BDSM. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) City Research Online Original citation: Cannon-Gibbs, S. (2016). The dichotomy of ‘them and us’ thinking in Counselling Psychology incorporating an empirical study on BDSM. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/16215/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. The dichotomy of ‘them and us’ thinking in Counselling Psychology incorporating an empirical study on BDSM. Sarah Cannon-Gibbs Portfolio submitted in fulfilment of DPsych Counselling Psychology, Department of Psychology, City University, London December, 2016 City, University of London Northampton Square London EC1V 0HB United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 7040 5060 THE FOLLOWING PART OF THIS THESIS HAS BEEN REDACTED FOR COPYRIGHT REASONS: pp. -

Download-Area/Document- Download$.Cfm?File Uuid=C1013D10- 1143-DFD0-7E63-610789798D82&Ext=Ppt

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Cannon-Gibbs, S. (2016). The dichotomy of ‘them and us’ thinking in Counselling Psychology incorporating an empirical study on BDSM. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16215/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The dichotomy of ‘them and us’ thinking in Counselling Psychology incorporating an empirical study on BDSM. Sarah Cannon-Gibbs Portfolio submitted in fulfilment of DPsych Counselling Psychology, Department of Psychology, City University, London December, 2016 City, University of London Northampton Square London EC1V 0HB United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 7040 5060 THE FOLLOWING PART OF THIS THESIS HAS BEEN REDACTED FOR COPYRIGHT REASONS: pp. 178-204: Publishable paper. “The more we talk about it the less sure I am of what comes under this umbrella.” A thematic analysis exploring how trainee Therapists talk and think about BDSM. -

The Ties That Bind Nov 13-26, 2014

THE ISSUE THE TIES THAT BIND From Sparta to Weimar Germany, kink has always been part of our sexuality JP LAROCQUE PHOTOS BY N MAXWELL LANDER Master Tony leads me down a darkened hallway And according to professional dominant and were actually fighting in the war. Men who had Meanwhile, underground leather culture in his apartment, stopping before a single door. BDSM educator Scarlet Riot, consenting to gone overseas had camaraderie and a fraternity, thrived in many major cities where gay com- “Would you like to see my playroom?” restrictive or controlled experiences has always and they loved each other — not in a sexual sense, munities had sprung up after the war, including We enter what was once a bedroom, but that provided significant emotional relief to people but in that they looked out for each other.” New York and San Francisco. Mr Leather and Mr has now been transformed into something very who led otherwise stressful lives and were sub- “And a lot of men, when they came back, Drummer contests were established early on, diferent. A leather sling hangs from the ceiling ject to strict socioeconomic divisions. couldn’t go back to their old lifestyle simply and magazines like Physique Pictorial popular- before a closet filled with various types of leather “Giving in to some type of physical anguish has because they enjoyed the hierarchy of things. ized images of the male form that were overtly fetish gear. Erotic artwork and posters hang on been an important element of many antique and Some men appreciated having a superior ofcer homoerotic.