Cross Keys Valve House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020

Maryland State Archives Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 Annual Report of the State Archivist to the Governor and General Assembly (State Government Article, § 9-1007(d)) Timothy D. Baker State Archivist and Commissioner of Land Patents August 2020 Maryland State Archives 350 Rowe Boulevard · Annapolis, MD 21401 410-260-6400 · http://msa.maryland.gov MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 This Page Left Blank MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 This Page Left Blank MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 Table of Contents Agency Organization & Overview of Activities . 3 Hall of Records Commission Meeting of November 14, 2019 Agenda . 27 Minutes . .47 Chronology of Staff Events. .55 Records Retention Schedules . .65 Disposal Certificate Approvals . .. .70 Records Received . .78 Special Collections Received . 92 Hall of Records Commission Meeting of May 08, 2020 Agenda . .93 Minutes . .115 Chronology of Staff Activities . .121 Records Retention Schedules . .129 Disposal Certificate Approvals . 132 Records Received . 141 Special Collections Received . .. 158 Maryland Commission on Artistic Property Meeting of Agenda . 159 Minutes . 163 MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 This Page Left Blank 2 MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 STATE ARCHIVES ANNUAL REPORT FY 2020 OVERVIEW · Hall of Records Commission Agenda, Fall 2019 · Hall of Records Commission Agenda, Spring 2020 · Commission on Artistic Property Agenda, Fall 2019 The State Archives was created in 1935 as the Hall of Records and reorganized under its present name in 1984 (Chapter 286, Acts of 1984). Upon that reorganization the Commission on Artistic Property was made part of the State Archives. As Maryland's historical agency, the State Archives is the central depository for government records of permanent value. -

Gunpowder River

Table of Contents 1. Polluted Runoff in Baltimore County 2. Map of Baltimore County – Percentage of Hard Surfaces 3. Baltimore County 2014 Polluted Runoff Projects 4. Fact Sheet – Baltimore County has a Problem 5. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Back River 6. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Gunpowder River 7. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Middle River 8. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Patapsco River 9. FAQs – Polluted Runoff and Fees POLLUTED RUNOFF IN BALTIMORE COUNTY Baltimore County contains the headwaters for many of the streams and tributaries feeding into the Patapsco River, one of the major rivers of the Chesapeake Bay. These tributaries include Bodkin Creek, Jones Falls, Gwynns Falls, Patapsco River Lower North Branch, Liberty Reservoir and South Branch Patapsco. Baltimore County is also home to the Gunpowder River, Middle River, and the Back River. Unfortunately, all of these streams and rivers are polluted by nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment and are considered “impaired” by the Maryland Department of the Environment, meaning the water quality is too low to support the water’s intended use. One major contributor to that pollution and impairment is polluted runoff. Polluted runoff contaminates our local rivers and streams and threatens local drinking water. Water running off of roofs, driveways, lawns and parking lots picks up trash, motor oil, grease, excess lawn fertilizers, pesticides, dog waste and other pollutants and washes them into the streams and rivers flowing through our communities. This pollution causes a multitude of problems, including toxic algae blooms, harmful bacteria, extensive dead zones, reduced dissolved oxygen, and unsightly trash clusters. -

Open Swab Final Thesis B.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY BUILDING SUBURBAN LIFE: ROLAND PARK, BALTIMORE AND THE REGULATION OF SPACE JOHN JOSEPH SWAB SPRING 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Geography and History with honors in Geography Reviewed and approved* by the following: Deryck W. Holdsworth Professor of Geography Thesis Supervisor Roger M. Downs Professor of Geography Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT An understudied example of an early modern suburb, Roland Park, Baltimore (constructed 1891- 1915) bridges the gap between the streetcar suburbs of the late nineteenth century and the tract suburbs of the mid-twentieth century. As an early modern suburb, the development of the Roland Park led to the formalization and creation of many of the social and cultural norms in addition to the landscape elements of today’s modern suburbs. This thesis examines these elements, by-products of the formation of an elite community, focusing on the regulation of Roland Park’s space in protecting it from the real and perceived negative influences of the outside world. Moreover, the thesis explores in depth the peopling of Roland Park’s built environment, a topic of great importance to the success of the community. Finally, the research places Roland Park in the larger spatial and temporal contexts of the development of other Baltimore communities, of other elite suburban developments within the United States, and the broader, global history of suburbs. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................ -

Greater Roland Park Master Plan

GREATER ROLAND PARK MASTER PLAN Approved by the Baltimore City Planning Commission February 17, 2011 Submitted By The Communities of the Greater Roland Park Master Plan 5115B Roland Avenue Baltimore, MD 21210 GREATER ROLAND PARK MASTER PLAN Contents Plan Vision Planning Commission Adoption Planning Department Report Planning Commission Members Executive Summary Acronyms List of Stakeholders Summary of Master Planning Process Acknowledgements Description of Roland Park Today (pending) Implementation Implementation Summary Table 1. Open Space and Recreation Table 1.1: Open Space Implementation Summary Figure 1.1: Stony Run Watershed Figure 1.2: Stony Run Park and Trail Capital Improvements Appendix 1.A: Design Guidelines for the Redevelopment of the Roland Water Tower 2. Transportation Table 2.1: Transportation Implementation Summary Figure 2.1: MTA Transit Map Figure 2.2: Traffic Count Analysis Figure 2.3: Gilman/Roland Avenue Turning Lane Diagram Figure 2.4: Existing Street Section Page i Figure 2.5: Curb Extension Street Section Figure 2.6: Paths/Open Space Map Network Figure 2.7: Crosswalks Precedent Figure 2.8: Curb Extensions Precedent Figure 2.9: Special Intersection Paving Precedent Figure 2.10: Pedestrian Refuge Island Precedent Figure 2.11: Baltimore’s Bicycle Master Plan Figure 2.12: Roland Avenue Section Figure 2.13: Cycle Track Figure 2.14: Cold Spring Lane 3. Housing Table 3.1: Housing Implementation Summary Figure 3.1: Greater Roland Park Area Appendix 3.A: Model Set of Design Guidelines for Buildings in Greater Roland Park -

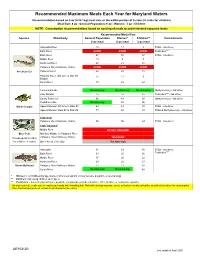

Recommended Maximum Fish Meals Each Year For

Recommended Maximum Meals Each Year for Maryland Waters Recommendation based on 8 oz (0.227 kg) meal size, or the edible portion of 9 crabs (4 crabs for children) Meal Size: 8 oz - General Population; 6 oz - Women; 3 oz - Children NOTE: Consumption recommendations based on spacing of meals to avoid elevated exposure levels Recommended Meals/Year Species Waterbody General PopulationWomen* Children** Contaminants 8 oz meal 6 oz meal 3 oz meal Anacostia River 15 11 8 PCBs - risk driver Back River AVOID AVOID AVOID Pesticides*** Bush River 47 35 27 PCBs - risk driver Middle River 13 9 7 Northeast River 27 21 16 Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor AVOID AVOID AVOID American Eel Patuxent River 26 20 15 Potomac River (DC Line to MD 301 1511 9 Bridge) South River 37 28 22 Centennial Lake No Advisory No Advisory No Advisory Methylmercury - risk driver Lake Roland 12 12 12 Pesticides*** - risk driver Liberty Reservoir 96 48 48 Methylmercury - risk driver Tuckahoe Lake No Advisory 93 56 Black Crappie Upper Potomac: DC Line to Dam #3 64 49 38 PCBs - risk driver Upper Potomac: Dam #4 to Dam #5 77 58 45 PCBs & Methylmercury - risk driver Crab meat Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 96 96 24 PCBs - risk driver Crab "mustard" Middle River DO NOT CONSUME Blue Crab Mid Bay: Middle to Patapsco River (1 meal equals 9 crabs) Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor "MUSTARD" (for children: 4 crabs ) Other Areas of the Bay Eat Sparingly Anacostia 51 39 30 PCBs - risk driver Back River 33 25 20 Pesticides*** Middle River 37 28 22 Northeast River 29 22 17 Brown Bullhead Patapsco River/Baltimore Harbor 17 13 10 South River No Advisory No Advisory 88 * Women = of childbearing age (women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, or are nursing) ** Children = all young children up to age 6 *** Pesticides = banned organochlorine pesticide compounds (include chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, or heptachlor epoxide) As a general rule, make sure to wash your hands after handling fish. -

Patapsco River History

Patapsco River History Welcome to NOAA's Patapsco River interpretive buoy, located at latitude 39 degrees 9.11 minutes north longitude 76 degrees 23.47 minutes west. It lies in the upper Chesapeake just east of the intersections of the Craig Hill and Brewerton ship channels entering in the Patapsco River in Baltimore's harbor from the south and north, respectively. The buoy sits in 20 feet of water surrounded by shallower lumps that would have been large oyster reefs when Captain John Smith and his crew arrived here, June 12, 1608, during their first exploratory voyage up the bay that summer. After leaving the Eastern Shore and crossing the bay to the Calvert Cliffs Smith and his crew sailed North in this direction. "We passed" he said "many shallow creeks" and that would be including today's West, Roads, South, Severn and Magothy Rivers, "but the first we found navigable for a ship we called Bolas. For the to clay in many places under the cliffs by the high water mark did grow up in red and white knots which made us thinke it Bole-Armoniack and Terra sigillata.", which were medicinal clays of the day. Over the next 2 days captain and crew continued up river to today's Elkridge placing a cross there, naming the spot Bland's Content and then coming back down stream to map the river with remarkable accuracy. They found no natives during this time, apparently this part of the Chesapeake western shore was a buffer zone between the Patuxent tribes to the south and the powerful, warlike Massawomeck and Susquehannock people to the north. -

Baltimore, MD November 17 – 20, 2011

The Society for American City and Regional Planning History Presents the s . a . c . r . p . h . Tremont Plaza Hotel Baltimore, MD November 17 – 20, 2011 baltimore 2011 Fourteenth National Conference on Planning History Preliminary Program Society for American City and Regional Planning History November 17-20, 2011 Baltimore, Maryland On behalf of the SACRPH Program Committee, our Local Arrangements Committee, and all those who have worked hard to get us ready for the biennial conference, we welcome you to Baltimore for the 14th National Conference on Planning History. This year marks the 25th anniversary of SACRPH’s founding, and we are delighted to see that the organization continues to grow and diversify. The 2009 conference boasted a record number of sessions—54 of them—but 2011 brought in unprecedented numbers of proposals, yielding a program that has now expanded to 74 paper sessions. For the first time, we have extended the regular portion of the program into Sunday. The conference has grown larger, but this is not because the Program Committee reduced standards. All paper and panel proposals were read and rated by at least 3 different members of the Committee, and we accepted only those with high rankings. Fortunately, paper quality seems to be keeping pace with the growth of the organization. Although have added many more sessions, we have not shortened them or crowded in more presenters. Instead, we have kept to SACRPH’s traditional emphasis on permitting time for discussion, by endeavoring to give 3-paper sessions 105 minutes, and 4-paper sessions a full two hours. -

2021 GBC Member Directory

GREATER BALTIMORE COMMITTEE Member Directory Anne Arundel County Baltimore City Baltimore County Carroll County Harford County Howard County Regional business leaders creating a better tomorrow . today. Greater Baltimore Committee Member Directory Message to Members Awards 3 17 2021 Board of Directors Year in Photos 4 21 GBC at a Glance 11 Year in Review 29 Vision, Mission and 2020 Programs, Regional Perspective 11 Projects and 29 Core Pillars for a Highlights Competitive Business 11 Advocacy Environment 31 Events and 2021 Membership by Communications for 12 Industry Guide 33 Member Engagement 2021 Member Directory 36 Committees 13 Preparing for the Future: 2020 Event Sponsors 7 A Regional Workforce 1 Development Initiative 14 Inside Report Advertisers’ Index Back Cover GBC’s Next Up Program CONTENTS 15 www.gbc.org | 1 INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE UP T.RowePrice Our commitment to positive change is supported through sponsorships, youth programming, volunteerism, and pro bono service. We are an organization focused on transforming communities. troweprice.com/responsibility CCON0061882 202009-1355�17 Message to Members It is an understatement to say that 2020 has been a unique, difficult and • Commit to creating a more representative Board of Directors. challenging year. However, despite the disruptions to normal business • Evaluating and deciding each GBC public policy position through operations brought about by the coronavirus pandemic and other an equity lens. societal challenges, the work of the GBC in its 65th year has remained • Conducting a series of programs to educate and provide needed strong and we expect an even stronger 2021. resources so GBC member and non-member companies can create Like many of you, the GBC has adapted to meet the challenges and has inclusive business environments. -

Ronnie Kroell Time,” Paul Liller, the GLCCB’S De- Velopment Associate, Told Outloud

May 08, 2009 | Volume VII, Issue 10 | LGBT Life in Maryland Pride 2009 Off and Running An By Steve Charing With the recent crowning of King and Queen of Pride (see inside), Interview Baltimore Pride is off and running and is on target for another fun-filled celebration that officially takes place with the weekend of June 20-21. It rep- resents the 34th time that the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Super- Community Center of Baltimore and Central Maryland (GLCCB) has run the annual event in Baltimore. model “Pride has evolved from an ac- tivist event to one where the commu- nity can celebrate and have a good Ronnie Kroell time,” Paul Liller, the GLCCB’s De- velopment Associate, told OUTloud. This is Liller’s first year as the official Pride coordinator, but he has done By Josh Aterovis similar work as a volunteer in previ- ous years’ Pride celebrations. Ronnie Kroell is more than just a Where at one time Baltimore’s pretty face. He’s best known for Pride was confined to either one day appearing on the first season of or two days in June, over the past Bravo’s Make Me A Supermod- several years, the celebration be- el, where his cuddly bromance gan earlier with a series of events with fellow model and straight that lead up to the big day. Following friend, Ben, sent gay viewers the King and Queen of Pride Pag- — and many women, too — into eant held on April 24, a succession convulsions of ecstasy. They of other pre-Pride events has been even got one of those sickening- scheduled. -

2000 Data Report Gunpowder River, Patapsco/Back River West Chesapeake Bay and Patuxent River Watersheds

2000 Data Report Gunpowder River, Patapsco/Back River West Chesapeake Bay and Pat uxent River Watersheds Gunpowder River Basin Patapsco /Back River Basin Patuxent River Basin West Chesapeake Bay Basin TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 3 GUNPOWDER RIVER SUB-BASIN ............................................................................. 9 GUNPOWDER RIVER....................................................................................................... 10 LOWER BIG GUNPOWDER FALLS ................................................................................... 16 BIRD RIVER.................................................................................................................... 22 LITTLE GUNPOWDER FALLS ........................................................................................... 28 MIDDLE RIVER – BROWNS............................................................................................. 34 PATAPSCO RIVER SUB-BASIN................................................................................. 41 BACK RIVER .................................................................................................................. 43 BODKIN CREEK .............................................................................................................. 49 JONES FALLS .................................................................................................................. 55 GWYNNS FALLS ............................................................................................................ -

Introduction

Notes Introduction Notes to Pages 1–7 1. When William Donald Schaefer left his final term unfinished in order to become state governor, Clarence “Du” Burns, an African American and chairman of the City Council, succeeded Schaefer, finished his term, and thus technically became the first black mayor. 2. Sandy Banisky and Ann LoLordo, “Kurt Schmoke Sworn in as 46th Mayor of Baltimore,” Baltimore Sun, December 11, 1987. Schmoke is quoted in Marion E. Orr, “Black Mayors and Human-Capital Enhancement Policies: A Study of Baltimore,” unpublished paper presented at National Conference of Black Political Scientists, March 1991. 3. Michael Ollove, “Schmoke Takes a Sizeable Political Risk by Assuming Responsibility for Schools,” Baltimore Sun, July 3, 1988. 4. The statistics of poor performance by students in the Baltimore public school system were rehearsed in numerous reports, including the Abell Foundation, “A Growing Inequality, a Report on the Financial Condition of the Baltimore City Public Schools,” Baltimore, 1989; Governor’s Commission on School Funding, “Report,” Baltimore, January 1994; Governor’s Commission on School Performance, “The Report of,” Annapolis, 1989; Commission for Students at Risk, “Maryland’s Challenge,” Annapolis, January 1990; Peter L. Szanton, “Baltimore 2000, a Choice of Futures,” Baltimore: Morris Goldseker Foundation, 1986. To compare the local education studies with national studies of public education, see U.S. Excellence in Education Commission, “A Nation At Risk,” Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Education, 1983; Task Force on Education for Economic Growth, “Action for Excellence,” Washington, DC, 1983; Editors of Education Week, Charting a Course for Reform (Washington, DC: Editorial Projects in Education, 1993). -

Garitee V. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore: a Gilded Age Debate on the Role and Limits of Local Government

Garitee v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore: A Gilded Age Debate on the Role and Limits of Local Government Kevin Attridge JD Candidate, May 2010 University of Maryland School of Law James Risk MA Candidate, History, May 2011 University of Maryland, Baltimore County Attridge & Risk - 1 I. Introduction In 1877, William L. Garitee brought suit against the city of Baltimore in what would become a pivotal case in public nuisance for the state of Maryland. Four years earlier, Daniel Constantine, a city contractor, began dumping in the Patapsco River between Colgate Creek and Sollers Point. The dredge came from the excavation of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and improvements being made to the Jones Falls Canal. Constantine’s dumping directly affected William Garitee’s ability to conduct business from his wharf because the dumping reduced the depth of the river, making it impossible to access Garitee’s dock by ship. After making several attempts to get the city to stop dumping, Garitee was forced to file suit against the city. The Superior Court for Baltimore City decided the case in favor of the city, a decision Garitee appealed. The appeal was heard in the March term of 1880 by the Maryland Court of Appeals. Under Judge Richard Henry Alvey, the Court overturned the lower court’s decision and remanded the case to allow Garitee to proceed with his public nuisance claim and award damages. Politically, Garitee v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore was part of the larger on- going debate on the role of government. During the Gilded Age, the Federal Government assumed a laissez-faire stance toward business, but the Progressive Era that immediately followed witnessed a restraint of business through the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act and the trust-busting administration of President Theodore Roosevelt.