Relativity Notes: Shankar, 2006 [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relativistic Dynamics

Chapter 4 Relativistic dynamics We have seen in the previous lectures that our relativity postulates suggest that the most efficient (lazy but smart) approach to relativistic physics is in terms of 4-vectors, and that velocities never exceed c in magnitude. In this chapter we will see how this 4-vector approach works for dynamics, i.e., for the interplay between motion and forces. A particle subject to forces will undergo non-inertial motion. According to Newton, there is a simple (3-vector) relation between force and acceleration, f~ = m~a; (4.0.1) where acceleration is the second time derivative of position, d~v d2~x ~a = = : (4.0.2) dt dt2 There is just one problem with these relations | they are wrong! Newtonian dynamics is a good approximation when velocities are very small compared to c, but outside of this regime the relation (4.0.1) is simply incorrect. In particular, these relations are inconsistent with our relativity postu- lates. To see this, it is sufficient to note that Newton's equations (4.0.1) and (4.0.2) predict that a particle subject to a constant force (and initially at rest) will acquire a velocity which can become arbitrarily large, Z t ~ d~v 0 f ~v(t) = 0 dt = t ! 1 as t ! 1 . (4.0.3) 0 dt m This flatly contradicts the prediction of special relativity (and causality) that no signal can propagate faster than c. Our task is to understand how to formulate the dynamics of non-inertial particles in a manner which is consistent with our relativity postulates (and then verify that it matches observation, including in the non-relativistic regime). -

OCC D 5 Gen5d Eee 1305 1A E

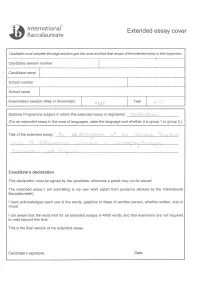

this cover and their final version of the extended essay to is are not is chose to write about applications of differential calculus because she found a great interest in it during her IB Math class. She wishes she had time to complete a deeper analysis of her topic; however, her busy schedule made it difficult so she is somewhat disappointed with the outcome of her essay. It was a pleasure meeting with when she was able to and her understanding of her topic was evident during our viva voce. I, too, wish she had more time to complete a more thorough investigation. Overall, however, I believe she did well and am satisfied with her essay. must not use Examiner 1 Examiner 2 Examiner 3 A research 2 2 D B introduction 2 2 c 4 4 D 4 4 E reasoned 4 4 D F and evaluation 4 4 G use of 4 4 D H conclusion 2 2 formal 4 4 abstract 2 2 holistic 4 4 Mathematics Extended Essay An Investigation of the Various Practical Uses of Differential Calculus in Geometry, Biology, Economics, and Physics Candidate Number: 2031 Words 1 Abstract Calculus is a field of math dedicated to analyzing and interpreting behavioral changes in terms of a dependent variable in respect to changes in an independent variable. The versatility of differential calculus and the derivative function is discussed and highlighted in regards to its applications to various other fields such as geometry, biology, economics, and physics. First, a background on derivatives is provided in regards to their origin and evolution, especially as apparent in the transformation of their notations so as to include various individuals and ways of denoting derivative properties. -

Time-Derivative Models of Pavlovian Reinforcement Richard S

Approximately as appeared in: Learning and Computational Neuroscience: Foundations of Adaptive Networks, M. Gabriel and J. Moore, Eds., pp. 497–537. MIT Press, 1990. Chapter 12 Time-Derivative Models of Pavlovian Reinforcement Richard S. Sutton Andrew G. Barto This chapter presents a model of classical conditioning called the temporal- difference (TD) model. The TD model was originally developed as a neuron- like unit for use in adaptive networks (Sutton and Barto 1987; Sutton 1984; Barto, Sutton and Anderson 1983). In this paper, however, we analyze it from the point of view of animal learning theory. Our intended audience is both animal learning researchers interested in computational theories of behavior and machine learning researchers interested in how their learning algorithms relate to, and may be constrained by, animal learning studies. For an exposition of the TD model from an engineering point of view, see Chapter 13 of this volume. We focus on what we see as the primary theoretical contribution to animal learning theory of the TD and related models: the hypothesis that reinforcement in classical conditioning is the time derivative of a compos- ite association combining innate (US) and acquired (CS) associations. We call models based on some variant of this hypothesis time-derivative mod- els, examples of which are the models by Klopf (1988), Sutton and Barto (1981a), Moore et al (1986), Hawkins and Kandel (1984), Gelperin, Hop- field and Tank (1985), Tesauro (1987), and Kosko (1986); we examine several of these models in relation to the TD model. We also briefly ex- plore relationships with animal learning theories of reinforcement, including Mowrer’s drive-induction theory (Mowrer 1960) and the Rescorla-Wagner model (Rescorla and Wagner 1972). -

Lie Time Derivative £V(F) of a Spatial Field F

Lie time derivative $v(f) of a spatial field f • A way to obtain an objective rate of a spatial tensor field • Can be used to derive objective Constitutive Equations on rate form D −1 Definition: $v(f) = χ? Dt (χ? (f)) Procedure in 3 steps: 1. Pull-back of the spatial tensor field,f, to the Reference configuration to obtain the corresponding material tensor field, F. 2. Take the material time derivative on the corresponding material tensor field, F, to obtain F_ . _ 3. Push-forward of F to the Current configuration to obtain $v(f). D −1 Important!|Note that the material time derivative, i.e. Dt (χ? (f)) is executed in the Reference configuration (rotation neutralized). Recall that D D χ−1 (f) = (F) = F_ = D F Dt ?(2) Dt v d D F = F(X + v) v d and hence, $v(f) = χ? (DvF) Thus, the Lie time derivative of a spatial tensor field is the push-forward of the directional derivative of the corresponding material tensor field in the direction of v (velocity vector). More comments on the Lie time derivative $v() • Rate constitutive equations must be formulated based on objective rates of stresses and strains to ensure material frame-indifference. • Rates of material tensor fields are by definition objective, since they are associated with a frame in a fixed linear space. • A spatial tensor field is said to transform objectively under superposed rigid body motions if it transforms according to standard rules of tensor analysis, e.g. A+ = QAQT (preserves distances under rigid body rotations). -

Solutions to Assignments 05

Solutions to Assignments 05 1. It is useful to first recall how this works in the case of classical mechanics (i.e. a 0+1 dimensional “field theory”). Consider a Lagrangian L(q; q_; t) that is a total time-derivative, i.e. d @F @F L(q; q_; t) = F (q; t) = + q_(t) : (1) dt @t @q(t) Then one has @L @2F @2F = + q_(t) (2) @q(t) @q(t)@t @q(t)2 and @L @F d @L @2F @2F = ) = + q_(t) (3) @q_(t) @q(t) dt @q_(t) @t@q(t) @q(t)2 Therefore one has @L d @L = identically (4) @q(t) dt @q_(t) Now we consider the field theory case. We define d @W α @W α @φ(x) L := W α(φ; x) = + dxα @xα @φ(x) @xα α α = @αW + @φW @αφ (5) to compute the Euler-Lagrange equations for it. One gets @L = @ @ W α + @2W α@ φ (6) @φ φ α φ α d @L d α β β = β @φW δα dx @(@βφ) dx β 2 β = @β@φW + @φW @βφ : (7) Thus (since partial derivatives commute) the Euler-Lagrange equations are satis- fied identically. Remark: One can also show the converse: if a Lagrangian L gives rise to Euler- Lagrange equations that are identically satisfied then (locally) the Lagrangian is a total derivative. The proof is simple. Assume that L(q; q_; t) satisfies @L d @L ≡ (8) @q dt @q_ identically. The left-hand side does evidently not depend on the acceleration q¨. -

Hamilton-Jacobi Theory for Hamiltonian and Non-Hamiltonian Systems

JOURNAL OF GEOMETRIC MECHANICS doi:10.3934/jgm.2020024 c American Institute of Mathematical Sciences Volume 12, Number 4, December 2020 pp. 563{583 HAMILTON-JACOBI THEORY FOR HAMILTONIAN AND NON-HAMILTONIAN SYSTEMS Sergey Rashkovskiy Ishlinsky Institute for Problems in Mechanics of the Russian Academy of Sciences Vernadskogo Ave., 101/1 Moscow, 119526, Russia (Communicated by David Mart´ınde Diego) Abstract. A generalization of the Hamilton-Jacobi theory to arbitrary dy- namical systems, including non-Hamiltonian ones, is considered. The general- ized Hamilton-Jacobi theory is constructed as a theory of ensemble of identi- cal systems moving in the configuration space and described by the continual equation of motion and the continuity equation. For Hamiltonian systems, the usual Hamilton-Jacobi equations naturally follow from this theory. The pro- posed formulation of the Hamilton-Jacobi theory, as the theory of ensemble, allows interpreting in a natural way the transition from quantum mechanics in the Schr¨odingerform to classical mechanics. 1. Introduction. In modern physics, the Hamilton-Jacobi theory occupies a spe- cial place. On the one hand, it is one of the formulations of classical mechanics [8,5, 12], while on the other hand it is the Hamilton-Jacobi theory that is the clas- sical limit into which quantum (wave) mechanics passes at ~ ! 0. In particular, the Schr¨odingerequation describing the motion of quantum particles, in the limit ~ ! 0, splits into two real equations: the classical Hamilton-Jacobi equation and the continuity equation for some ensemble of classical particles [9]. Thus, it is the Hamilton-Jacobi theory that is the bridge that connects the classical mechanics of point particles with the wave mechanics of quantum objects. -

An Essay on Lagrangian and Eulerian Kinematics of Fluid Flow

Lagrangian and Eulerian Representations of Fluid Flow: Kinematics and the Equations of Motion James F. Price Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, 02543 [email protected], http://www.whoi.edu/science/PO/people/jprice June 7, 2006 Summary: This essay introduces the two methods that are widely used to observe and analyze fluid flows, either by observing the trajectories of specific fluid parcels, which yields what is commonly termed a Lagrangian representation, or by observing the fluid velocity at fixed positions, which yields an Eulerian representation. Lagrangian methods are often the most efficient way to sample a fluid flow and the physical conservation laws are inherently Lagrangian since they apply to moving fluid volumes rather than to the fluid that happens to be present at some fixed point in space. Nevertheless, the Lagrangian equations of motion applied to a three-dimensional continuum are quite difficult in most applications, and thus almost all of the theory (forward calculation) in fluid mechanics is developed within the Eulerian system. Lagrangian and Eulerian concepts and methods are thus used side-by-side in many investigations, and the premise of this essay is that an understanding of both systems and the relationships between them can help form the framework for a study of fluid mechanics. 1 The transformation of the conservation laws from a Lagrangian to an Eulerian system can be envisaged in three steps. (1) The first is dubbed the Fundamental Principle of Kinematics; the fluid velocity at a given time and fixed position (the Eulerian velocity) is equal to the velocity of the fluid parcel (the Lagrangian velocity) that is present at that position at that instant. -

Chapter 3: Relativistic Dynamics

Chapter 3 Relativistic dynamics A particle subject to forces will undergo non-inertial motion. According to Newton, there is a simple relation between force and acceleration, f~ = m~a; (3.0.1) and acceleration is the second time derivative of position, d~v d2~x ~a = = : (3.0.2) dt dt2 There is just one problem with these relations | they are wrong! Newtonian dynamics is a good approximation when velocities are very small compared to c, but outside this regime the relation (3.0.1) is simply incorrect. In particular, these relations are inconsistent with our relativity postu- lates. To see this, it is sufficient to note that Newton's equations (3.0.1) and (3.0.2) predict that a particle subject to a constant force (and initially at rest) will acquire a velocity which can become arbitrarily large, Z t ~ d~v 0 f ~v(t) = 0 dt = t −! 1 as t ! 1 . (3.0.3) 0 dt m This flatly contradicts the prediction of special relativity (and causality) that no signal can propagate faster than c. Our task is to understand how to formulate the dynamics of non-inertial particles in a manner which is consistent with our relativity postulates (and then verify that it matches observation). 3.1 Proper time The result of solving for the dynamics of some object subject to known forces should be a prediction for its position as a function of time. But whose time? One can adopt a particular reference frame, and then ask to find the spacetime position of the object as a function of coordinate time t in the chosen frame, xµ(t), where as always, x0 ≡ c t. -

The Action, the Lagrangian and Hamilton's Principle

The Action, the Lagrangian and Hamilton's principle Physics 6010, Fall 2010 The Action, the Lagrangian and Hamilton's principle Relevant Sections in Text: x1.4{1.6, x2.1{2.3 Variational Principles A great deal of what we shall do in this course hinges upon the fact that one can de- scribe a wide variety of dynamical systems using variational principles. You have probably already seen the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian ways of formulating mechanics; these stem from variational principles. We shall make a great deal of fuss about these variational for- mulations in this course. I will not try to completely motivate the use of these formalisms at this early point in the course since the motives are so many and so varied; you will see the utility of the formalism as we proceed. Still, it is worth commenting a little here on why these principles arise and are so useful. The appearance of variational principles in classical mechanics can in fact be traced back to basic properties of quantum mechanics. This is most easily seen using Feynman's path integral formalism. For simplicity, let us just think about the dynamics of a point particle in 3-d. Very roughly speaking, in the path integral formalism one sees that the probability amplitude for a particle to move from one place, r1, to another, r2, is given by adding up the probability amplitudes for all possible paths connecting these two positions (not just the classically allowed trajectory). The amplitude for a given path r(t) is of the i S[r] form e h¯ , where S[r] is the action functional for the trajectory. -

Basic Equations

2.20 { Marine Hydrodynamics, Fall 2006 Lecture 2 Copyright °c 2006 MIT - Department of Mechanical Engineering, All rights reserved. 2.20 { Marine Hydrodynamics Lecture 2 Chapter 1 - Basic Equations 1.1 Description of a Flow To de¯ne a flow we use either the `Lagrangian' description or the `Eulerian' description. ² Lagrangian description: Picture a fluid flow where each fluid particle caries its own properties such as density, momentum, etc. As the particle advances its properties may change in time. The procedure of describing the entire flow by recording the detailed histories of each fluid particle is the Lagrangian description. A neutrally buoyant probe is an example of a Lagrangian measuring device. The particle properties density, velocity, pressure, . can be mathematically repre- sented as follows: ½p(t);~vp(t); pp(t);::: The Lagrangian description is simple to understand: conservation of mass and New- ton's laws apply directly to each fluid particle . However, it is computationally expensive to keep track of the trajectories of all the fluid particles in a flow and therefore the Lagrangian description is used only in some numerical simulations. r υ p (t) p Lagrangian description; snapshot 1 ² Eulerian description: Rather than following each fluid particle we can record the evolution of the flow properties at every point in space as time varies. This is the Eulerian description. It is a ¯eld description. A probe ¯xed in space is an example of an Eulerian measuring device. This means that the flow properties at a speci¯ed location depend on the location and on time. For example, the density, velocity, pressure, . -

Effects of Transformed Hamiltonians on Hamilton-Jacobi Theory in View of a Stronger Connection to Wave Mechanics

Effects of transformed Hamiltonians on Hamilton-Jacobi theory in view of a stronger connection to wave mechanics Michele Marrocco* ENEA (Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energies and Sustainable Economic Development) via Anguillarese 301, I-00123 Rome, Italy & Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Roma ‘La Sapienza’ P.le Aldo Moro 5, I-00185 Rome, Italy Abstract Hamilton-Jacobi theory is a fundamental subject of classical mechanics and has also an important role in the development of quantum mechanics. Its conceptual framework results from the advantages of transformation theory and, for this reason, relates to the features of the generating function of canonical transformations connecting a specific Hamiltonian to a new Hamiltonian chosen to simplify Hamilton’s equations of motion. Usually, the choice is between and a cyclic depending on the new conjugate momenta only. Here, we investigate more general representations of the new Hamiltonian. Furthermore, it is pointed out that the two common alternatives of and a cyclic should be distinguished in more detail. An attempt is made to clearly discern the two regimes for the harmonic oscillator and, not surprisingly, some correspondences to the quantum harmonic oscillator appear. Thanks to this preparatory work, generalized coordinates and momenta associated with the Hamilton’s principal function (i.e., ) are used to determine dependences in the Hamilton’s characteristic function (i.e., cyclic ). The procedure leads to the Schrödinger’s equation where the Hamilton’s characteristic function plays the role of the Schrödinger’s wave function, whereas the first integral invariant of Poincaré takes the place of the reduced Planck constant. This finding advances the pedagogical value of the Hamilton-Jacobi theory in view of an introduction to Schrödinger’s wave mechanics without the tools of quantum mechanics. -

Chapter 2 Lagrange's and Hamilton's Equations

Chapter 2 Lagrange’s and Hamilton’s Equations In this chapter, we consider two reformulations of Newtonian mechanics, the Lagrangian and the Hamiltonian formalism. The first is naturally associated with configuration space, extended by time, while the latter is the natural description for working in phase space. Lagrange developed his approach in 1764 in a study of the libration of the moon, but it is best thought of as a general method of treating dynamics in terms of generalized coordinates for configuration space. It so transcends its origin that the Lagrangian is considered the fundamental object which describes a quantum field theory. Hamilton’s approach arose in 1835 in his unification of the language of optics and mechanics. It too had a usefulness far beyond its origin, and the Hamiltonian is now most familiar as the operator in quantum mechanics which determines the evolution in time of the wave function. We begin by deriving Lagrange’s equation as a simple change of coordi- nates in an unconstrained system, one which is evolving according to New- ton’s laws with force laws given by some potential. Lagrangian mechanics is also and especially useful in the presence of constraints, so we will then extend the formalism to this more general situation. 35 36 CHAPTER 2. LAGRANGE’S AND HAMILTON’S EQUATIONS 2.1 Lagrangian for unconstrained systems For a collection of particles with conservative forces described by a potential, we have in inertial cartesian coordinates mx¨i = Fi. The left hand side of this equation is determined by the kinetic energy func- tion as the time derivative of the momentum pi = ∂T/∂x˙ i, while the right hand side is a derivative of the potential energy, ∂U/∂x .AsT is indepen- − i dent of xi and U is independent ofx ˙ i in these coordinates, we can write both sides in terms of the Lagrangian L = T U, which is then a function of both the coordinates and their velocities.