Introduction to Differential Equations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 11 Line Integrals of Vector-Valued Functions (Cont'd)

Lecture 11 Line integrals of vector-valued functions (cont’d) In the previous lecture, we considered the following physical situation: A force, F(x), which is not necessarily constant in space, is acting on a mass m, as the mass moves along a curve C from point P to point Q as shown in the diagram below. z Q P m F(x(t)) x(t) C y x The goal is to compute the total amount of work W done by the force. Clearly the constant force/straight line displacement formula, W = F · d , (1) where F is force and d is the displacement vector, does not apply here. But the fundamental idea, in the “Spirit of Calculus,” is to break up the motion into tiny pieces over which we can use Eq. (1 as an approximation over small pieces of the curve. We then “sum up,” i.e., integrate, over all contributions to obtain W . The total work is the line integral of the vector field F over the curve C: W = F · dx . (2) ZC Here, we summarize the main steps involved in the computation of this line integral: 1. Step 1: Parametrize the curve C We assume that the curve C can be parametrized, i.e., x(t)= g(t) = (x(t),y(t), z(t)), t ∈ [a, b], (3) so that g(a) is point P and g(b) is point Q. From this parametrization we can compute the velocity vector, ′ ′ ′ ′ v(t)= g (t) = (x (t),y (t), z (t)) . (4) 1 2. Step 2: Compute field vector F(g(t)) over curve C F(g(t)) = F(x(t),y(t), z(t)) (5) = (F1(x(t),y(t), z(t), F2(x(t),y(t), z(t), F3(x(t),y(t), z(t))) , t ∈ [a, b] . -

Notes on Partial Differential Equations John K. Hunter

Notes on Partial Differential Equations John K. Hunter Department of Mathematics, University of California at Davis Contents Chapter 1. Preliminaries 1 1.1. Euclidean space 1 1.2. Spaces of continuous functions 1 1.3. H¨olderspaces 2 1.4. Lp spaces 3 1.5. Compactness 6 1.6. Averages 7 1.7. Convolutions 7 1.8. Derivatives and multi-index notation 8 1.9. Mollifiers 10 1.10. Boundaries of open sets 12 1.11. Change of variables 16 1.12. Divergence theorem 16 Chapter 2. Laplace's equation 19 2.1. Mean value theorem 20 2.2. Derivative estimates and analyticity 23 2.3. Maximum principle 26 2.4. Harnack's inequality 31 2.5. Green's identities 32 2.6. Fundamental solution 33 2.7. The Newtonian potential 34 2.8. Singular integral operators 43 Chapter 3. Sobolev spaces 47 3.1. Weak derivatives 47 3.2. Examples 47 3.3. Distributions 50 3.4. Properties of weak derivatives 53 3.5. Sobolev spaces 56 3.6. Approximation of Sobolev functions 57 3.7. Sobolev embedding: p < n 57 3.8. Sobolev embedding: p > n 66 3.9. Boundary values of Sobolev functions 69 3.10. Compactness results 71 3.11. Sobolev functions on Ω ⊂ Rn 73 3.A. Lipschitz functions 75 3.B. Absolutely continuous functions 76 3.C. Functions of bounded variation 78 3.D. Borel measures on R 80 v vi CONTENTS 3.E. Radon measures on R 82 3.F. Lebesgue-Stieltjes measures 83 3.G. Integration 84 3.H. Summary 86 Chapter 4. -

MULTIVARIABLE CALCULUS (MATH 212 ) COMMON TOPIC LIST (Approved by the Occidental College Math Department on August 28, 2009)

MULTIVARIABLE CALCULUS (MATH 212 ) COMMON TOPIC LIST (Approved by the Occidental College Math Department on August 28, 2009) Required Topics • Multivariable functions • 3-D space o Distance o Equations of Spheres o Graphing Planes Spheres Miscellaneous function graphs Sections and level curves (contour diagrams) Level surfaces • Planes o Equations of planes, in different forms o Equation of plane from three points o Linear approximation and tangent planes • Partial Derivatives o Compute using the definition of partial derivative o Compute using differentiation rules o Interpret o Approximate, given contour diagram, table of values, or sketch of sections o Signs from real-world description o Compute a gradient vector • Vectors o Arithmetic on vectors, pictorially and by components o Dot product compute using components v v v v v ⋅ w = v w cosθ v v v v u ⋅ v = 0⇔ u ⊥ v (for nonzero vectors) o Cross product Direction and length compute using components and determinant • Directional derivatives o estimate from contour diagram o compute using the lim definition t→0 v v o v compute using fu = ∇f ⋅ u ( u a unit vector) • Gradient v o v geometry (3 facts, and understand how they follow from fu = ∇f ⋅ u ) Gradient points in direction of fastest increase Length of gradient is the directional derivative in that direction Gradient is perpendicular to level set o given contour diagram, draw a gradient vector • Chain rules • Higher-order partials o compute o mixed partials are equal (under certain conditions) • Optimization o Locate and -

Engineering Analysis 2 : Multivariate Functions

Multivariate functions Partial Differentiation Higher Order Partial Derivatives Total Differentiation Line Integrals Surface Integrals Engineering Analysis 2 : Multivariate functions P. Rees, O. Kryvchenkova and P.D. Ledger, [email protected] College of Engineering, Swansea University, UK PDL (CoE) SS 2017 1/ 67 Multivariate functions Partial Differentiation Higher Order Partial Derivatives Total Differentiation Line Integrals Surface Integrals Outline 1 Multivariate functions 2 Partial Differentiation 3 Higher Order Partial Derivatives 4 Total Differentiation 5 Line Integrals 6 Surface Integrals PDL (CoE) SS 2017 2/ 67 Multivariate functions Partial Differentiation Higher Order Partial Derivatives Total Differentiation Line Integrals Surface Integrals Introduction Recall from EG189: analysis of a function of single variable: Differentiation d f (x) d x Expresses the rate of change of a function f with respect to x. Integration Z f (x) d x Reverses the operation of differentiation and can used to work out areas under curves, and as we have just seen to solve ODEs. We’ve seen in vectors we often need to deal with physical fields, that depend on more than one variable. We may be interested in rates of change to each coordinate (e.g. x; y; z), time t, but sometimes also other physical fields as well. PDL (CoE) SS 2017 3/ 67 Multivariate functions Partial Differentiation Higher Order Partial Derivatives Total Differentiation Line Integrals Surface Integrals Introduction (Continue ...) Example 1: the area A of a rectangular plate of width x and breadth y can be calculated A = xy The variables x and y are independent of each other. In this case, the dependent variable A is a function of the two independent variables x and y as A = f (x; y) or A ≡ A(x; y) PDL (CoE) SS 2017 4/ 67 Multivariate functions Partial Differentiation Higher Order Partial Derivatives Total Differentiation Line Integrals Surface Integrals Introduction (Continue ...) Example 2: the volume of a rectangular plate is given by V = xyz where the thickness of the plate is in z-direction. -

Relativistic Dynamics

Chapter 4 Relativistic dynamics We have seen in the previous lectures that our relativity postulates suggest that the most efficient (lazy but smart) approach to relativistic physics is in terms of 4-vectors, and that velocities never exceed c in magnitude. In this chapter we will see how this 4-vector approach works for dynamics, i.e., for the interplay between motion and forces. A particle subject to forces will undergo non-inertial motion. According to Newton, there is a simple (3-vector) relation between force and acceleration, f~ = m~a; (4.0.1) where acceleration is the second time derivative of position, d~v d2~x ~a = = : (4.0.2) dt dt2 There is just one problem with these relations | they are wrong! Newtonian dynamics is a good approximation when velocities are very small compared to c, but outside of this regime the relation (4.0.1) is simply incorrect. In particular, these relations are inconsistent with our relativity postu- lates. To see this, it is sufficient to note that Newton's equations (4.0.1) and (4.0.2) predict that a particle subject to a constant force (and initially at rest) will acquire a velocity which can become arbitrarily large, Z t ~ d~v 0 f ~v(t) = 0 dt = t ! 1 as t ! 1 . (4.0.3) 0 dt m This flatly contradicts the prediction of special relativity (and causality) that no signal can propagate faster than c. Our task is to understand how to formulate the dynamics of non-inertial particles in a manner which is consistent with our relativity postulates (and then verify that it matches observation, including in the non-relativistic regime). -

OCC D 5 Gen5d Eee 1305 1A E

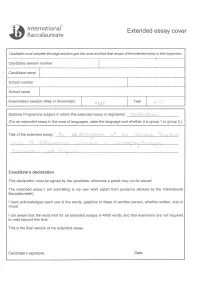

this cover and their final version of the extended essay to is are not is chose to write about applications of differential calculus because she found a great interest in it during her IB Math class. She wishes she had time to complete a deeper analysis of her topic; however, her busy schedule made it difficult so she is somewhat disappointed with the outcome of her essay. It was a pleasure meeting with when she was able to and her understanding of her topic was evident during our viva voce. I, too, wish she had more time to complete a more thorough investigation. Overall, however, I believe she did well and am satisfied with her essay. must not use Examiner 1 Examiner 2 Examiner 3 A research 2 2 D B introduction 2 2 c 4 4 D 4 4 E reasoned 4 4 D F and evaluation 4 4 G use of 4 4 D H conclusion 2 2 formal 4 4 abstract 2 2 holistic 4 4 Mathematics Extended Essay An Investigation of the Various Practical Uses of Differential Calculus in Geometry, Biology, Economics, and Physics Candidate Number: 2031 Words 1 Abstract Calculus is a field of math dedicated to analyzing and interpreting behavioral changes in terms of a dependent variable in respect to changes in an independent variable. The versatility of differential calculus and the derivative function is discussed and highlighted in regards to its applications to various other fields such as geometry, biology, economics, and physics. First, a background on derivatives is provided in regards to their origin and evolution, especially as apparent in the transformation of their notations so as to include various individuals and ways of denoting derivative properties. -

Year 6 Local Linearity and L'hopitals.Notebook December 04, 2018

Year 6 Local Linearity and L'Hopitals.notebook December 04, 2018 New Divider! Application of Derivatives: Local Linearity and L'Hopitals Local Linear Approximation Do Now: For each sketch the function, write the equation of the tangent line at x = 0 and include the tangent line in your sketch. 1) 2) In general, if a function f is differentiable at an x, then a sufficiently magnified portion of the graph of f centered at the point P(x, f(x)) takes on the appearance of a ______________ line segment. For this reason, a function that is differentiable at x is sometimes said to be locally linear at x. 1 Year 6 Local Linearity and L'Hopitals.notebook December 04, 2018 How is this useful? We are pretty good at finding the equations of tangent lines for various functions. Question: Would you rather evaluate linear functions or crazy ridiculous functions such as higher order polynomials, trigonometric, logarithmic, etc functions? Evaluate sec(0.3) The idea is to use the equation of the tangent line to a point on the curve to help us approximate the function values at a specific x. Get it??? Probably not....here is an example of a problem I would like us to be able to approximate by the end of the class. Without the use of a calculator approximate . 2 Year 6 Local Linearity and L'Hopitals.notebook December 04, 2018 Local Linear Approximation General Proof Directions would say, evaluate f(a). If f(x) you find this impossible for some y reason, then that's how you would recognize we need to use local linear approximation! You would: 1) Draw in a tangent line at x = a. -

Time-Derivative Models of Pavlovian Reinforcement Richard S

Approximately as appeared in: Learning and Computational Neuroscience: Foundations of Adaptive Networks, M. Gabriel and J. Moore, Eds., pp. 497–537. MIT Press, 1990. Chapter 12 Time-Derivative Models of Pavlovian Reinforcement Richard S. Sutton Andrew G. Barto This chapter presents a model of classical conditioning called the temporal- difference (TD) model. The TD model was originally developed as a neuron- like unit for use in adaptive networks (Sutton and Barto 1987; Sutton 1984; Barto, Sutton and Anderson 1983). In this paper, however, we analyze it from the point of view of animal learning theory. Our intended audience is both animal learning researchers interested in computational theories of behavior and machine learning researchers interested in how their learning algorithms relate to, and may be constrained by, animal learning studies. For an exposition of the TD model from an engineering point of view, see Chapter 13 of this volume. We focus on what we see as the primary theoretical contribution to animal learning theory of the TD and related models: the hypothesis that reinforcement in classical conditioning is the time derivative of a compos- ite association combining innate (US) and acquired (CS) associations. We call models based on some variant of this hypothesis time-derivative mod- els, examples of which are the models by Klopf (1988), Sutton and Barto (1981a), Moore et al (1986), Hawkins and Kandel (1984), Gelperin, Hop- field and Tank (1985), Tesauro (1987), and Kosko (1986); we examine several of these models in relation to the TD model. We also briefly ex- plore relationships with animal learning theories of reinforcement, including Mowrer’s drive-induction theory (Mowrer 1960) and the Rescorla-Wagner model (Rescorla and Wagner 1972). -

Which Moments of a Logarithmic Derivative Imply Quasiinvariance?

Doc Math J DMV Which Moments of a Logarithmic Derivative Imply Quasi invariance Michael Scheutzow Heinrich v Weizsacker Received June Communicated by Friedrich Gotze Abstract In many sp ecial contexts quasiinvariance of a measure under a oneparameter group of transformations has b een established A remarkable classical general result of AV Skorokhod states that a measure on a Hilb ert space is quasiinvariant in a given direction if it has a logarithmic aj j derivative in this direction such that e is integrable for some a In this note we use the techniques of to extend this result to general oneparameter families of measures and moreover we give a complete char acterization of all functions for which the integrability of j j implies quasiinvariance of If is convex then a necessary and sucient condition is that log xx is not integrable at Mathematics Sub ject Classication A C G Overview The pap er is divided into two parts The rst part do es not mention quasiinvariance at all It treats only onedimensional functions and implicitly onedimensional measures The reason is as follows A measure on R has a logarithmic derivative if and only if has an absolutely continuous Leb esgue density f and is given by 0 f x ae Then the integrability of jj is equivalent to the Leb esgue x f 0 f jf The quasiinvariance of is equivalent to the statement integrability of j f that f x Leb esgueae Therefore in the case of onedimensional measures a function allows a quasiinvariance criterion as indicated in the abstract -

Notes for Math 136: Review of Calculus

Notes for Math 136: Review of Calculus Gyu Eun Lee These notes were written for my personal use for teaching purposes for the course Math 136 running in the Spring of 2016 at UCLA. They are also intended for use as a general calculus reference for this course. In these notes we will briefly review the results of the calculus of several variables most frequently used in partial differential equations. The selection of topics is inspired by the list of topics given by Strauss at the end of section 1.1, but we will not cover everything. Certain topics are covered in the Appendix to the textbook, and we will not deal with them here. The results of single-variable calculus are assumed to be familiar. Practicality, not rigor, is the aim. This document will be updated throughout the quarter as we encounter material involving additional topics. We will focus on functions of two real variables, u = u(x;t). Most definitions and results listed will have generalizations to higher numbers of variables, and we hope the generalizations will be reasonably straightforward to the reader if they become necessary. Occasionally (notably for the chain rule in its many forms) it will be convenient to work with functions of an arbitrary number of variables. We will be rather loose about the issues of differentiability and integrability: unless otherwise stated, we will assume all derivatives and integrals exist, and if we require it we will assume derivatives are continuous up to the required order. (This is also generally the assumption in Strauss.) 1 Differential calculus of several variables 1.1 Partial derivatives Given a scalar function u = u(x;t) of two variables, we may hold one of the variables constant and regard it as a function of one variable only: vx(t) = u(x;t) = wt(x): Then the partial derivatives of u with respect of x and with respect to t are defined as the familiar derivatives from single variable calculus: ¶u dv ¶u dw = x ; = t : ¶t dt ¶x dx c 2016, Gyu Eun Lee. -

Lie Time Derivative £V(F) of a Spatial Field F

Lie time derivative $v(f) of a spatial field f • A way to obtain an objective rate of a spatial tensor field • Can be used to derive objective Constitutive Equations on rate form D −1 Definition: $v(f) = χ? Dt (χ? (f)) Procedure in 3 steps: 1. Pull-back of the spatial tensor field,f, to the Reference configuration to obtain the corresponding material tensor field, F. 2. Take the material time derivative on the corresponding material tensor field, F, to obtain F_ . _ 3. Push-forward of F to the Current configuration to obtain $v(f). D −1 Important!|Note that the material time derivative, i.e. Dt (χ? (f)) is executed in the Reference configuration (rotation neutralized). Recall that D D χ−1 (f) = (F) = F_ = D F Dt ?(2) Dt v d D F = F(X + v) v d and hence, $v(f) = χ? (DvF) Thus, the Lie time derivative of a spatial tensor field is the push-forward of the directional derivative of the corresponding material tensor field in the direction of v (velocity vector). More comments on the Lie time derivative $v() • Rate constitutive equations must be formulated based on objective rates of stresses and strains to ensure material frame-indifference. • Rates of material tensor fields are by definition objective, since they are associated with a frame in a fixed linear space. • A spatial tensor field is said to transform objectively under superposed rigid body motions if it transforms according to standard rules of tensor analysis, e.g. A+ = QAQT (preserves distances under rigid body rotations). -

A Logarithmic Derivative Lemma in Several Complex Variables and Its Applications

TRANSACTIONS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 363, Number 12, December 2011, Pages 6257–6267 S 0002-9947(2011)05226-8 Article electronically published on June 27, 2011 A LOGARITHMIC DERIVATIVE LEMMA IN SEVERAL COMPLEX VARIABLES AND ITS APPLICATIONS BAO QIN LI Abstract. We give a logarithmic derivative lemma in several complex vari- ables and its applications to meromorphic solutions of partial differential equa- tions. 1. Introduction The logarithmic derivative lemma of Nevanlinna is an important tool in the value distribution theory of meromorphic functions and its applications. It has two main forms (see [13, 1.3.3 and 4.2.1], [9, p. 115], [4, p. 36], etc.): Estimate (1) and its consequence, Estimate (2) below. Theorem A. Let f be a non-zero meromorphic function in |z| <R≤ +∞ in the complex plane with f(0) =0 , ∞. Then for 0 <r<ρ<R, 1 2π f (k)(reiθ) log+ | |dθ 2π f(reiθ) (1) 0 1 1 1 ≤ c{log+ T (ρ, f) + log+ log+ +log+ ρ +log+ +log+ +1}, |f(0)| ρ − r r where k is a positive integer and c is a positive constant depending only on k. Estimate (1) with k = 1 was originally due to Nevanlinna, which easily implies the following version of the lemma with exceptional intervals of r for meromorphic functions in the plane: 1 2π f (reiθ) (2) + | | { } log iθ dθ = O log(rT(r, f )) , 2π 0 f(re ) for all r outside a countable union of intervals of finite Lebesgue measure, by using the Borel lemma in a standard way (see e.g.