“This Was the Reason I Was Born”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mohawk Post the Voice of Millis High School

The Mohawk Post The Voice of Millis High School SENIOR EDITION: Congratulations Class of 2018 Millis High School Announces Valedictorian Nick Steiner and Salutatorian Elana Carleton From Millis High School Principal Robert Mullaney: Millis High School is proud to announce the Valedictorian and Salutatorian for its graduating Class of 2018. Nicholas Steiner will be recognized at graduation ceremonies as the Class Valedictorian. Nicholas achieved the highest cumulative grade point average for the class. He is a member of Millis High School’s Chorus and National Honor Society. He has been the recipient of the Harvard Book Award and the George Washington University Medal for Excellence in Science. Nicholas is very active at the Franklin School for the Performing Arts where he has been a member of the Broadway Lads and Broadway Light Musical Theater Troupe. He has performed in various musicals including Shrek, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Spamalot, and Les Miserables, and has served as accompanist for a number of shows. Nick will be attending Northeastern University where he will study engineering and also pursue vocal performance. Nicholas is the son of Brian and Christine Steiner of Millis. Elana Carleton is Millis High School’s Salutatorian. Elana has been an active member of Leo’s Club, Amnesty Club, and Chemistry Club. She is president of Common Ground and secretary of National Honor Society. She was the recipient of the Barnard College Book Award. She has also been involved as a tutor and has participated in over two hundred hours of community service in high school. Elana will be majoring in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the Commonwealth College of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. -

L'elysée Montmartre Ticket Reservation

A member of X-Japan in France ! Ra :IN in Paris the 5th of May 2005 Gfdgfd We have the pleasure to announce that the solo band of PATA (ex-X-Japan), Ra :IN, will perform live at the Elysee Montmartre in Paris (France) the 5th of May 2005. " Ra:IN " (pronounced "rah'een")----is an amazing unique, powerful new rock trio consisting of PATA (guitar-Tomoaki Ishizuka), one of the guitarists from the legendary Japanese rock band X Japan, michiaki (bass-Michiaki Suzuki), originally from another legendary Yokohama based rock band TENSAW, and Tetsu Mukaiyama (drums), who supported various bands and musicians such as Red Warriors and CoCCo. " Ra:IN " 's uniqueness comes from its musical eloquence. The three-piece band mainly delves into instrumental works, and the band's combination of colorful tones and sounds, along with the tight playing only possible with top-notch skilled players, provides an overwhelming power and energy that is what " ROCK " is all about. Just cool and heavy rhythms. But above all, don’t miss the first opportunity to see on stage in Europe a member of X-Japan, PATA (one of the last still performing). One of those that with their music, during years, warmed the heart of millions of fans in Japan and across the world. Ra :IN live in Paris website : http://parisvisualprod.free.fr Ra :IN website : http://www.rain-web.com Ticket Reservation Europe : Pre-Sales on Official Event Website : http://parisvisualprod.free.fr Japan : For Fan tour, please contact : [email protected] Worlwide (From 01st of March 2005) : TICKETNET -

Bakalářská Práce

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Bakalářská práce Martina Lakomá Vývoj Heavy metalu se zaměřením na ženské interprety Olomouc 2018 Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip T. Krejčí, Ph.D. Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma „Vývoj Heavy metalu se zaměřením na ženské interprety“ vypracovala samostatně, s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů. V Prosenicích dne 11. 4. 2018 ………………………… Podpis autora práce Poděkování Ráda bych touto cestou poděkovala všem, kteří mi pomáhali s realizací mé bakalářské práce. Především mému vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu T. Krejčímu, Ph.D. za jeho ochotu a cenné rady. Velký dík také patří mé rodině a přátelům, kteří mě podporovali a inspirovali jak po dobu psaní práce, tak po celý čas mého studia. Anotace Bakalářská práce se zabývá vývojem hudebního žánru zvaného heavy metal. Celkově je rozdělena do čtyř částí, jejíž první část osvětluje pojem metal a metalovou subkulturu. Následující text zpracovává nejen jeho první projevy, ale i důležité milníky v čele s Black Sabbath, které metal formovaly. Chronologicky sestavuje obraz jeho zrodu a postupného rozvoje v další nekonečné množství subžánrů. Tyto odnože jsou nastíněny jak jejich charakteristikami, tak nejvýznamnějšími zástupci. Práce je do určité míry zaměřena i na vliv žen v tomto stylu. Proto se snaží nalézt stopy hudebnic či čistě ženských hudebních skupin v daných subžánrech, a na konci pátrání shrnout zjištěné poznatky. Klíčová slova pojem heavy metal, subkultura, vývoj, Black Sabbath, metalové subžánry, ženy v metalu Abstract The bachelor thesis is concerned with the development of the musical genre called “heavy metal“. It comprises four parts. The first chapter defines the terms – metal and metal subculture. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Press Release – Global X Japan Launches Global X

Press Release Global X Japan launches Global X Digital Innovation Japan ETF, its first engagement with Solactive 27 January 2021 Global X Japan, a joint venture between Global X ETFs and Daiwa Securities established in 2020, launched its new Global X Digital Innovation Japan ETF [Ticker: 2626] on January 27th, 2021, on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. This release marks Global X’s first engagement with Solactive on Japanese ground after Global X, a sub-brand of Mirae Asset Global Investments, issued multiple successful ETFs tracking Solactive indices in HK, Europe, and the US. The Global X Digital Innovation Japan ETF tracks Solactive’s Digital Innovation Japan Index, which is powered by ARTIS®, Solactive’s proprietary big data and natural language processing algorithm. The index includes an ESG screening carried out by ESG data provider Minerva Analytics Ltd. The screening excludes companies not compliant with the UN Global Compact and businesses affiliated with controversial industries. Japan is pushing for digitalization. The country’s plan to establish a new governmental Digitalization Agency by September 20211 owes to the fact that the state’s current lack of digitalization could burden its economy with an annual cost of, according to some estimates, 12 trillion yen (about 116 billion USD)2. Pioneering companies in this field could benefit from the resulting surge in demand and political initiatives. The Index The Solactive Digital Innovation Japan Index includes Japanese companies that are pioneers in digital innovation and, therefore, represents companies that are likely to contribute to the Japanese societal transformation plans. The Solactive Digital Innovation Japan Index includes eleven sub-themes of digital innovation: Cloud Computing; Cyber Security; Remote Communications; Online Project and Document Management; Online Healthcare and Telemedicine; Digital, Online, and Video Gaming; Video and Media streaming; Online Education; Social Networks; E-commerce; and E-payments. -

A Multi-Dimensional Study of the Emotion in Current Japanese Popular Music

Acoust. Sci. & Tech. 34, 3 (2013) #2013 The Acoustical Society of Japan PAPER A multi-dimensional study of the emotion in current Japanese popular music Ryo Yonedaà and Masashi Yamada Graduate School of Engineering, Kanazawa Institute of Technology, 7–1 Ohgigaoka, Nonoich, 921–8501 Japan ( Received 22 March 2012, Accepted for publication 5 September 2012 ) Abstract: Musical psychologists illustrated musical emotion with various numbers of dimensions ranging from two to eight. Most of them concentrated on classical music. Only a few researchers studied emotion in popular music, but the number of pieces they used was very small. In the present study, perceptual experiments were conducted using large sets of popular pieces. In Experiment 1, ten listeners rated musical emotion for 50 J-POP pieces using 17 SD scales. The results of factor analysis showed that the emotional space was constructed by three factors, ‘‘evaluation,’’ ‘‘potency’’ and ‘‘activity.’’ In Experiment 2, three musicians and eight non-musicians rated musical emotion for 169 popular pieces. The set of pieces included not only J-POP tunes but also Enka and western popular tunes. The listeners also rated the suitability for several listening situations. The results of factor analysis showed that the emotional space for the 169 pieces was spanned by the three factors, ‘‘evaluation,’’ ‘‘potency’’ and ‘‘activity,’’ again. The results of multiple-regression analyses suggested that the listeners like to listen to a ‘‘beautiful’’ tune with their lovers and a ‘‘powerful’’ and ‘‘active’’ tune in a situation where people were around them. Keywords: Musical emotion, Popular music, J-POP, Semantic differential method, Factor analysis PACS number: 43.75.Cd [doi:10.1250/ast.34.166] ‘‘activity’’ [3]. -

Get Ebook « Visual Kei Artists

QDKRCRTPLZU6 \ PDF « Visual kei artists Visual kei artists Filesize: 4.12 MB Reviews This pdf is indeed gripping and interesting. It is definitely simplistic but shocks within the 50 percent of your book. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Michael Spinka) DISCLAIMER | DMCA ZVKPJW8WNMMZ // Kindle \\ Visual kei artists VISUAL KEI ARTISTS Reference Series Books LLC Apr 2013, 2013. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x189x7 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 121. Chapters: X Japan, Buck-Tick, Dir En Grey, Alice Nine, Miyavi, Hide, Nightmare, The Gazette, Glacier, Merry, Luna Sea, Ayabie, Rentrer en Soi, Versailles, D'espairsRay, Malice Mizer, Girugamesh, Psycho le Cému, An Cafe, Penicillin, Laputa, Vidoll, Phantasmagoria, Mucc, Plastic Tree, Onmyo- Za, Panic Channel, Blood, The Piass, Megamasso, Tinc, Kagerou, Sid, Uchuu Sentai NOIZ, Fanatic Crisis, Moi dix Mois, Pierrot, Zi:Kill, Kagrra, Doremidan, Anti Feminism, Eight, Sug, Kuroyume, 12012, LM.C, Sadie, Baiser, Strawberry song orchestra, Unsraw, Charlotte, Dué le Quartz, Baroque, Silver Ash, Schwarz Stein, Inugami Circus-dan, Cali Gari, GPKism, Guniw Tools, Luci'fer Luscious Violenoue, Mix Speakers, Inc, Aion, Lareine, Ghost, Luis-Mary, Raphael, Vistlip, Deathgaze, Duel Jewel, El Dorado, Skin, Exist Trace, Cascade, The Dead Pop Stars, D'erlanger, The Candy Spooky Theater, Aliene Ma'riage, Matenrou Opera, Blam Honey, Kra, Fairy Fore, BIS, Lynch, Shazna, Die in Cries, Color, D=Out, By-Sexual, Rice, Dio - Distraught Overlord, Kaya, Jealkb, Genkaku Allergy, Karma Shenjing, L'luvia, Devil Kitty, Nheira. Excerpt: X Japan Ekkusu Japan ) is a Japanese heavy metal band founded in 1982 by Toshimitsu 'Toshi' Deyama and Yoshiki Hayashi. -

TEFAF Catalogue, Kigen (Genesis), Building, Japan / the Gotoh Museum, Japan / Herbert F

TEFAF Maastricht 2017 10th March – 19th March 2017 Opening Preview on 9th March Stand 237 (new location) The Yufuku Collection 2017 Our Raison D'etre 06 Hisao Domoto 42 Naoki Takeyama In recent years, the emergence of a group of Japanese artists who have spearheaded a new way of thinking in the realm of contemporary art has helped to shift paradigms and vanquish stereotypes borne from the 19th century, their art and aesthetic understood as making vital contributions to the broader history of modern and contemporary art. This new current, linked by the phrase Keisho-ha (School of Form), Sueharu Fukami Hidenori Tsumori 10 46 encompasses a movement of artists who, through the conscious selection of material and technique, create boldly innovative works that cannot be manifested by any other means. The term craft holds no true meaning to this movement, nor do the traditional dichotomies that have traditionally separated fine art 14 Satoru Ozaki 50 Nobuyuki Tanaka from craft art. In the words of Nietzsche, "Craft is dead." A new age beckons. No country exemplifies this expanding role more so than the artists of contemporary Japan, a country that continues to place premium on elegance in execution coupled with cutting-edge innovation within 18 Niyoko Ikuta 54 Kanjiro Moriyama tradition. No gallery represents this new movement more so than Yufuku, a gallery that has nurtured and represented the Keisho School from its conceptual inception. Michelangelo once said, "every block of stone has a statue inside, and it is the task of the sculptor to 22 Ken Mihara 58 Takahiro Yede discover it." Our artists are no different, wielding material and technique to create a unique aesthetic that can inspire future generations, yet would resonate with generations before us, regardless of age, creed or culture. -

Flnitflrcililcl

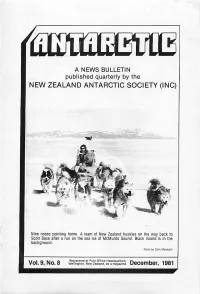

flNiTflRCililCl A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY (INC) svs-r^s* ■jffim Nine noses pointing home. A team of New Zealand huskies on the way back to Scott Base after a run on the sea ice of McMurdo Sound. Black Island is in the background. Pholo by Colin Monteath \f**lVOL Oy, KUNO. O OHegisierea Wellington, atNew kosi Zealand, uttice asHeadquarters, a magazine. n-.._.u—December, -*r\n*1981 SOUTH GEORGIA SOUTH SANDWICH Is- / SOUTH ORKNEY Is £ \ ^c-c--- /o Orcadas arg \ XJ FALKLAND Is /«Signy I.uk > SOUTH AMERICA / /A #Borga ) S y o w a j a p a n \ £\ ^> Molodezhnaya 4 S O U T H Q . f t / ' W E D D E L L \ f * * / ts\ xr\ussR & SHETLAND>.Ra / / lj/ n,. a nn\J c y DDRONNING d y ^ j MAUD LAND E N D E R B Y \ ) y ^ / Is J C^x. ' S/ E A /CCA« « • * C",.,/? O AT S LrriATCN d I / LAND TV^ ANTARCTIC \V DrushsnRY,a«feneral Be|!rano ARG y\\ Mawson MAC ROBERTSON LAND\ \ aust /PENINSULA'5^ *^Rcjnne J <S\ (see map below) VliAr^PSobral arg \ ^ \ V D a v i s a u s t . 3_ Siple _ South Pole • | U SA l V M I IAmundsen-Scott I U I I U i L ' l I QUEEN MARY LAND ^Mir"Y {ViELLSWORTHTTH \ -^ USA / j ,pt USSR. ND \ *, \ Vfrs'L LAND *; / °VoStOk USSR./ ft' /"^/ A\ /■■"j■ - D:':-V ^%. J ^ , MARIE BYRD\Jx^:/ce She/f-V^ WILKES LAND ,-TERRE , LAND \y ADELIE ,'J GEORGE VLrJ --Dumont d'Urville france Leningradskaya USSR ,- 'BALLENY Is ANTARCTIC PENIMSULA 1 Teniente Matienzo arg 2 Esperanza arg 3 Almirante Brown arg 4 Petrel arg 5 Deception arg 6 Vicecomodoro Marambio arg ' ANTARCTICA 7 Arturo Prat chile 8 Bernardo O'Higgins chile 9 P r e s i d e n t e F r e i c h i l e : O 5 0 0 1 0 0 0 K i l o m e t r e s 10 Stonington I. -

Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin This page intentionally left blank Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin University of Tokyo, Japan Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Murdoch University - PalgraveConnect - 2013-08-20 - PalgraveConnect University - licensed to Murdoch www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9781137283788 - Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, Edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin Introduction, selection -

TEFAF Catalogue, Entitled Sei (Awakening), Marks the Kanata Aesthetic, and We Are Proud to Have Represented Him for Over 25 Years

TEFAF MAASTRICHT 2021 TEFAF 2021 A LIGHTHOUSE A LIGHTHOUSE CALLED KANATA CALLED KANATA TEFAF Maastricht 2021 11th - 19th September Early Access (9th) VIP Preview (10th) Our Raison D'etre Yufuku Gallery ended its 27 years of existence in June 2020, and from its ashes was borne Indeed, a foreign audience has long supported Japanese aesthetics, and were often the first A Lighthouse called Kanata. to pick up on the beauty of things that the Japanese themselves could not see. Ukiyoe, Jakuchu, the Gutai School and the Mono-ha, Sugimoto, Kusama … these Japanese artists Kanata means “Beyond” or “Far Away” in Japanese, a romantic ideal imbued by the two and movements were virtually forgotten within Japan, yet had garnered global recognition CLAY GLASS characters that comprise it, literally meaning “Towards” and “You.” Towards you, I wish by its appreciation in Europe and America. Likewise, by highlighting Japanese aesthetics to be, but you are far away. This is a quintessentially Japanese ideal, filled with ambiguity outside of Japan, we hope for greater recognition of today’s artists by those who are willing Sueharu Fukami 8 Niyoko Ikuta 24 and nuance. to support them. And ultimately, it is our hope that such international recognition will go on to influence Japanese audiences, thereby reintroducing and reimporting our aesthetics Ken Mihara 10 Sachi Fujikake 26 Like much in our language, it gives the impression that you, of all persons, is far from me, within and throughout Japan. This will then lead to instil in future generations the beauty Keizo Sugitani 12 Masaaki Yonemoto 28 and yet, we long and yearn to be together. -

Metal W Cieniu Kwitnącej Wiśni. Specyfika I Przemiany Gatunku Na Gruncie Japońskim

FOLIA 258 Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis Studia de Cultura 10(3) 2018 ISSN 2083-7275 DOI 10.24917/20837275.10.3.10 Agnieszka Kiejziewicz 0000-0003-2546-6360 Uniwersytet Jagielloński Metal w cieniu kwitnącej wiśni. Specyfika i przemiany gatunku na gruncie japońskim Wstęp Japanīzu Metaru 1 Japońska muzyka metalowavisual kei (jap. ) , stanowiąca konglomerat wpły- wów zachodnich, rodzimej kultury2 muzycznej oraz estetyki powstałej na kanwie działań miłośników (Adamowicz 2014), podlega nieustannej ewolucji. Od momentu pojawienia się gatunku jako rozwinięcia popularnego w latach 70. XX wieku rocka, w następnych dekadach japoński metal dzielił się na kolejne podga- tunki, takie jak extreme metal w latach 80. czy nu metal w latach 90. Badając roz- wój japońskiej muzyki metalowej, nie można zapomnieć o jego związkach z rockiem i wspólnych korzeniach obydwu gatunków. Echa wyznaczników muzyki rockowej u jej początków na gruncie japońskim, takie jak kopiowanie wzorców zachodnich czy zamiłowanie do kreowania unikalnego wizerunku scenicznego artystów odbi- jają się w muzyce metalowej do dziś. Dlatego też istotne jest przedstawienie zarysu genezy rozwoju sceny rockabilly w latach 50. i 60. XX wieku, traktowanej jako pre- ludium do narodzin omawianego w niniejszym tekście gatunku. Pod koniec lat 60. pojawiły się pierwsze zespoły wychodzące poza granice wyznaczone przez muzykę rockową, dając podwaliny dla proto-metalu, którego prekursorem stała się grupa Flower Travellin’ Band, występująca wraz z piosen- karzem Yuyą Uchidą. Jako moment narodzin japońskiego metalu są wskazywane lata 70. XX wieku i założenie takich grup, jak Bow Wow (1975), 44 Magnum (1977) czy Earthshaker (1978). Natomiast kolejne dziesięciolecie przyniosło nie tylko roz- wój i poszerzanie grona fanów japońskiego metalu, ale również stało się okresem postępującej dywersyfikacji form.