Wildlife Conflict in Peppara Wildlife Sanctuary and Adjacent Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding REPORT of the WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL

Understanding REPORT OF THE WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL KERALA PERSPECTIVE KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD Preface The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel report and subsequent heritage tag accorded by UNESCO has brought cheers to environmental NGOs and local communities while creating apprehensions among some others. The Kerala State Biodiversity Board has taken an initiative to translate the report to a Kerala perspective so that the stakeholders are rightly informed. We need to realise that the whole ecosystem from Agasthyamala in the South to Parambikulam in the North along the Western Ghats in Kerala needs to be protected. The Western Ghats is a continuous entity and therefore all the 6 states should adopt a holistic approach to its preservation. The attempt by KSBB is in that direction so that the people of Kerala along with the political decision makers are sensitized to the need of Western Ghats protection for the survival of themselves. The Kerala-centric report now available in the website of KSBB is expected to evolve consensus of people from all walks of life towards environmental conservation and Green planning. Dr. Oommen V. Oommen (Chairman, KSBB) EDITORIAL Western Ghats is considered to be one of the eight hottest hot spots of biodiversity in the World and an ecologically sensitive area. The vegetation has reached its highest diversity towards the southern tip in Kerala with its high statured, rich tropical rain fores ts. But several factors have led to the disturbance of this delicate ecosystem and this has necessitated conservation of the Ghats and sustainable use of its resources. With this objective Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel was constituted by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) comprising of 14 members and chaired by Prof. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

Collected from Peppara Wildlife Sanctuary Parvati Menon VT

Checklist and approximate quantity of Non-Wood Forest Produce (NWFP) collected from Peppara Wildlife Sanctuary Parvati Menon V.T.M. N.S.S. College, Department of Botany, Thiruvananthapuram, India. 2002 [email protected] Keywords: biodiversity, checklists, forests, non wood forest produce, non timber forest products, illegal trade, wildlife sanctuaries, India. Abstract The Peppara Wildlife sanctuary is a traditional resource base for substantial non-wood forest produce (NWFP). Checklist of NWFP from the sanctuary is prepared on the basis of data collected over a period of one given month; it is subject to the season, availability, market demands and to the known trade outlets. Major items such as fuel wood, fodder and some medicinal plants have been quantified. The checklist includes products used at subsistence, local use and commercial levels. Acknowledgements From the traditional perspective on non-wood forest produce as just a source of commercial exploitation to the present one of conservation of the wealth of biodiversity, the managers of our forests have come a long way in the sustainable utilization of natural resources. I would like to thank Mr. T. Pradeep Kumar, Wildlife Warden, Thiruvananthapuram and his colleagues in the Dept. of Forests, Keralafor giving me this opportunity to study the trade on NWFP in this area and make a humble contribution to the conservation and management efforts now in way throughout the state. The services of Sri. Suneesh Kumar, S.K and Sri. P T Sudarsanan, in collecting the data and assistance in the fieldwork is gratefully acknowledged. I am also indebted to Sri.Bhagavan Kani and several other tribal elders and youngsters for the insight they provided into the life of their community. -

Thiruvananthapuram

Proceedings of the District Collector & Chairperson District Disaster Management Authority Thiruvananthapuram (Present: Dr:NavjotKhosa LAS) 5EARS THEELERATI MAHATHA (Issued u/s 26, 30, 34 of Disaster Management Act-2005) DDMA/01/2020/COVID/H7/CZ-183 Dtd:- 11.06.2021 Sub :COVID 19 SARS-CoV-2 Virus Outbreak Management Declaration of Containment Zones - Directions and Procedures- Orders issued- reg Read )GOMs)No.54/2020/H&FWD published as SRO No.243/2020 dtd 21.03.2020. 2)Order of Union Government No 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 01.05.2020. S) Order of Union Government No 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 29.08.2020. 4) G.O(Rt) No. 383/2021/DMD dated 26/04/2021 6)G.O(Rt) No. 391/2021/DMD dated 30/04/2021 )Report from District War room, Trivandrum dated 10/06/2021 ) DDMA decision dated 28/05/2021 8) G.O(Rt) No.455/2021/DMD dated 03/06/2021 9) G.O(Rt) No.459/2021/DMD dated 07/06/2021 WHEREAS, Covid-19, is declared as a global pandemic by the World Health Organisation. The Government of India also declared it as a disaster and announced several measures to mitigate the epidemic. Government of Kerala, has deployed several stringent measures to control the spread of the epidemic. Since strict surveillance is one of the most potent tool to prevent the occurrence of a community spread, the government has directed district administration to take all possible measures to prevent the epidemic. AND SRO WHEREAS, notification issued by Govt of Kerala as Kerala Epidemics Diseases, Covid 19, Regulations 2020 in official gazette stipulates that all possible measures shall be incorporated to contain the disease. -

Judicial I Class Magistrate Court - I, Nedumangad

JUDICIAL I CLASS MAGISTRATE COURT - I, NEDUMANGAD Information under Section 4(1)(b) of the Right to information Act, 2005 1. Organisation,functions and duties : The Judicial First Class Magistrate Court-I,Nedumangad is one of the Lower Criminal Courts of the District Judiciary and the Judicial First Class Magistrate is its head. The Judicial First Class Magistrate Court- I,Nedumangad is situated at Nedumangad Municipality in Thiruvananthapuram District.Chief Judcial Magistrate Thiruvananthapuram is the Controling Authority of this Court. Address: Judicial First Class Magistrate Court-I, First Floor,Court Complex, Nedumangad, Thiruvananthapuram Pin: 695541. Jurisdiction 1. Police Stations 1.Venjaramood 2.Vattappara 3. Aryanad 4. Valiyamala 5. Ponmudi 2. Excise Range Offices 1. Vamanapuram 2. Aryanad 3.Nedumangad 1. Sanctioned Strength Judicial Officer : 1 Junior Superintendent : 1 Confidential Assistant : 1 Senior Clerk : 3 Clerk : 4 Typist : 2 Office Attendant : 4 Part Time Sweeper : 1 2. The powers and duties of employees 1.Junior Superintendent 1. Preparation of Cash Books and Subsidiary Registers. 2. Collecting Fine Amounts, Keeping the Account Registers and Valuables. 3. Distribution of Thapals to various Sectons. 4. Distribution of O.Ms issued by all the Hon'ble higher courts for general information and compliance and for obtaining particulars if any relating to the O.Ms and forwarding the same to the respected Hon'ble Higher Courts. 5. Prepairing Expenditure and other related Statements, Quarterly Inspection Reports. 6. Budget preparation. 7. File Regarding judicial Officers. 8. All files related to disciplinary proceedings, all kinds of complaint put in by public against cases, Judicial Officers and staff members 9. -

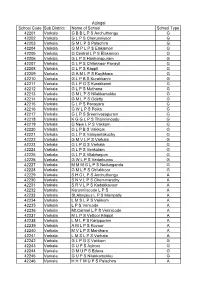

Attingal School Code Sub District Name of School School Type

Attingal School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 42201 Varkala G B B L P S Anchuthengu G 42202 Varkala G L P S Cherunniyoor G 42203 Varkala G M L P S Palachira G 42204 Varkala G M P L P S Elakamon G 42205 Varkala G Central L P S Elakamon G 42206 Varkala G L P S Hariharapuram G 42207 Varkala G L P S Chilakkoor Panayil G 42208 Varkala G L P S Kappil G 42209 Varkala G A M L P S Kayikkara G 42210 Varkala G L P B S Kurakkanni G 42211 Varkala G L P G S Kurakkanni G 42212 Varkala G L P S Muthana G 42213 Varkala G M L P S Nilakkamukku G 42214 Varkala G M L P S Odetty G 42215 Varkala G L P S Panayara G 42216 Varkala G W L P S Poika G 42217 Varkala G L P S Sreenivasapuram G 42218 Varkala K G G L P S Thannimoodu G 42219 Varkala G New L P S Vakkom G 42220 Varkala G L P B S Vakkom G 42221 Varkala G L P S Valayantakuzhy G 42222 Varkala G M V L P S Varkala G 42223 Varkala G L P G S Varkala G 42224 Varkala G L P S Venkulam G 42225 Varkala G L P S Vilabhagom G 42226 Varkala G W L P S Vedarkunnu G 42227 Varkala M M M G L P S Nedunganda G 42228 Varkala G M L P S Chilakkoor G 42229 Varkala S H C L P S Anchuthengu A 42230 Varkala S N V L P S Chemmaruthy A 42231 Varkala S R V L P S Kadakkavoor A 42232 Varkala Karunnilacode L P S A 42233 Varkala St.Alloysius L P S Mampally A 42234 Varkala L M S L P S Vakkom A 42235 Varkala L P S Vencode A 42236 Varkala Mt.Carmel L P S Vennicode A 42237 Varkala M L P S Vettoor Elappil A 42238 Varkala L M L P S Karippuram A 42239 Varkala A M L P S Kovoor A 42240 Varkala M V L P S Manthara A 42241 Varkala L M S L P -

DIOCESE of NEYYATTINKARA His Excellency Rt. Rev. Dr. Vincent Samuel S.T.D. Bishop of Neyyattinkara Bishop's House, Neyyattinka

DIOCESE OF NEYYATTINKARA His Excellency Rt. Rev. Dr. Vincent Samuel S.T.D. Bishop of Neyyattinkara Bishop’s House, Neyyattinkara, Aralummood P.O. Trivandrum – 695 123, Kerala, India : 0471-2223133, 2220693, Fax: 0471-2222262 :[email protected] : [email protected] Web : www.neyyattinkaradiocese.org B. 10.8.1950 / O. 19.12.1975 / E.O. 01.11.1996 F. 27th September 1. Very. Rev. Msgr. G. Christudas Vicar General Bishop’s House, Neyyattinkara Aralummood P.O. Trivandrum – 695 123 : 0471-2227137 (P), 2223133, 2220693 Mob. 9847069309,9447534132 : [email protected] [email protected] Manager Emmanuel College of Arts and Science &Emmaneul College of BEd. Training Vazhichal, Kudappanamood P.O Thiruvanathapuram : 0471-2248416, 2248113 : [email protected] [email protected] : www.emmanuelcollege.ac.in B. 14.01.1950 / O. 19.12.1975 / F. Christ the King 2. Very Rev. Msgr. D. Selvarajan JCD Episcopal Vicar &Regional Coordinator (Neyyattinkara Region) St. Xavier’s Church, Thirupuram Thirupuram P.O., Trivandrum - 695 133 Mob. 9447864433 & Director, Logos Pastoral Centre San Jose Nagar Neyyattinkara, Trivandrum – 695 121 : 0471-2221194 : [email protected] &. Judicial Vicar Bishop’s House, Neyyattinkara Aralummood P.O., Trivandrum – 695 123 : 0471- 2221941, 0471- 2222760 B. 27.01.1962 / O. 23.12.1987 / F. Christ the King 3. Very. Rev. Msgr. V.P. Jose Episcopal Vicar &Coordinator of Ministries Logos Pastoral Center, Neyyattinkara, San Jose Nagar 695121 &. P.P.,Our Lady of Assumption Forane Church Vlathankara P.O., Trivandrum – 695 134 : 0471-2236165, C. 2236617, Mob. 08547678999, 8921922356 [email protected] [email protected] B. 19.05.1967/ O. 12.04.1994 / F.19th March 4. -

Field Projects & Internships

IQAC – Government College Nedumangad, Thiruvananthapuram Field Projects & Internships GOVERNMENT COLLEGE NEDUMANGAD UNDER GOVERNMENT OF KERALA NEDUMANGAD, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM, KERALA- 695541 Accredited by NAAC with ‘B’ Grade IQAC – Government College Nedumangad, Thiruvananthapuram MCom – 2018-2019 Candidate Name of the Title of the Project/Study Guide code Candidate Role of Online Travelling 59017112001 Akhila V S Agencies(OTA) for the promotion of Dr. BijuA V E-Tourism in Kerala A study on marketing strategies of 59017112002 Anjali R P ReenaKumari D Swadeshi Self Help Group, Pattom Marketing problems of minor forest 59017112003 Anshad A Dr. BijuA V products of tribal peoples in kerala A study on Savings and Investment 59017112004 Archa S S Vijayan K habit among middle income group A study on the performance of Kudumbashree units with special 59017112005 Arya J P Dr. Anzer R N reference to PoovachalGramaPanchayath Evaluation of E-Governance services 59017112006 Aswathy L Dr. BijuA V in Trivandrum district A study on the problems of Agro- 59017112007 Dhanabalan M J Nazeem A tourism in Idukki district A study on financial literacy in 59017112008 Divya A S Indurajani R AnadGramaPanchayath A study on Online Taxi services: 59017112009 Gayathri D R Customers preferences and employees Dr. Anzer R N problems A study on Awareness of customers on payment Bank with special 59017112010 Hefsiba Joseph M L Nazeem A reference to ThiruvananthapuramDistrict A study on current scenario of 59017112011 Ragul P S different segments of food processing Rejani -

Details of the Dealership of Hpcl to Be Uploaded in the Portal South Zone State:Kerala Sr

Details in subsequent pages are as on 01/04/12 For information only. In case of any discrepancy, the official records prevail. DETAILS OF THE DEALERSHIP OF HPCL TO BE UPLOADED IN THE PORTAL SOUTH ZONE STATE:KERALA SR. No. Regional Office State Name of dealership Dealership address (incl. location, Dist, State, PIN) Name(s) of Proprietor/Partner(s) Outlet Telephone No. HPCL DEALERS, 13/770, NEAR NOORANAD JN., KP ROAD, 1 Cochin Kerala A S FUELS, NOORNAD NOORNADU, ALAPPUZHA DISTRICT, PIN:690504, KERALA MURALIDHARAN NAIR 9388867230 STATE. HPCL DEALERS, MC ROAD, VENJARAMUD, TRIVANDRUM 2 Cochin Kerala A.K. Jameela Begum A.K. Jameela Begum, Sheeja Shafi 9495154958 DISTRICT, PIN:695607, KERALA STATE. HPCL DEALERS, Chakkaraparambu, Ernakulam NH By Pass, 3 Cochin Kerala A.M. Sadick, NH Byepass Kanayannur, Ernakulam DISTRICT, PIN:682032, KERALA A.M. Sadick 9895290824 STATE. HPCL DEALERS, WARD 4/614 B, OPP: TASTE BUDS HOTEL, 4 Cochin Kerala A.N. Raman Pillai & Sons,Koothattukulam KOOTHATUKULAM JUNCTION, MC ROAD, KOOTHATUKULAM , R. Suresh kumar ERNAKULAM DISTRICT, PIN:686662, KERALA STATE. HPCL DEALERS, 378 WARD 8, NEAR NAINAR MOSQUE, NH 5 Cochin Kerala Al Ameen Corporation, Kanjirapally 220, KANJIRAPALLY, KOTTAYAM DISTRICT, PIN:686507, M.M. Syed Mohammed 9447316820 KERALA STATE. HPCL DEALERS, 15/393, NH-208, KOTTARAKARA, KOLLAM 6 Cochin Kerala Aleyamma Mathew, Kadappakada Prasad Mathew 9605006835 DISTRICT, PIN:691506, KERALA STATE. HPCL DEALERS, NEAR SASTRI JN, QS RD, KOLLAM, KOLLAM 7 Cochin Kerala Aleyamma Mathew, Kottarakkara Mathew Idiculla 9895974254 DISTRICT, PIN:691001, KERALA STATE. HPCL DEALERS, "5/1, NEAR Paravur Kavala, Paravur Kavala on 8 Cochin Kerala Alwaye Business Corporation, Alwaye NH-47, Alwaye, Ernakulam DISTRICT, PIN:683101, KERALA Smt. -

Inner Settings Final

Personal Data 2021 Name ............................................................................................. Office Address ............................................................................... ....................................................................................................... ....................................................................................................... Residential Address ........................................................................ ...................................................................................................... ...................................................................................................... Telephone ....................................................................................... Mobile ........................................................................................... Telefax ........................................................................................... E-mail ........................................................................................... Bank Account No. ...................... Income Tax PAN No. .................... Driving Licence No. .................. Passport No. ............................... Credit Card No. ............................................................................. Insurance Policy No. ..................................................................... Blood Group ................................................................................. Allergies -

2015-16 DRAFT BENEFICIARY LIST Sl

BACKWARD COMMUNITIES DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT BCDD/A1/991/13 DATE: 14/12/2015 VISWAKARMA PENSION - 2015-16 DRAFT BENEFICIARY LIST Sl. Appl. No. Name Address District Sub Caste Income Remarks No. THIRUVANANTHAPURAM TC/21/386,MADAN KOVIL THIRUVANANTHAP 1 4387 A SASTHAVU ACHARY THATTAN 12000 VEEDU,NEDUMCADU ROAD, KARAMANA URAM MELATHILPO,THIRUVANANTHAPURAM VEEDU , CHAVERCODE, 695002 , THIRUVANANTHAP 2 2878 AKHILAN N ASARI 18000 PARIPPALLY P.O. 691574 , URAM VISAKAMTHIRUVANANTHAPURAM KUZHTHALAMCODE , THANNIVILA THIRUVANANTHAP VISWAKARAMA/V 3 162 AMBIKA DEVI J 15000 BALARAMAPURAM P O , URAM ISWAKARMAS VIDYATHIRUVANANTHAPURAM BHAVAN KOKKOTHAMANGALAM 695501 THIRUVANANTHAP 4 1500 AMBIKA P ASARI 18000 NEDUMANGAD P O URAM SREE VIHAR, PACHALLOOR PO, , THIRUVANANTHAP 5 229 AMBIKA T ASARI 6000 THIRUVANANTHAPURAM,KERALA , URAM SREEVISHNU ATTINKUZHY KAZHAKUTTOM P THIRUVANANTHAP VISWAKARAMA/V 6 251 ANANDAN ASARI R 18000 O TRIVANDRUM, KERALA URAM ISWAKARMAS THOPILCHARIVILA PUTHEN VEEDU, THIRUVANANTHAP 7 581 APPUKUTTAN ASARI ASARI 18000 KOTTUKAL, KOTTUKAL.P.O, URAM THOPILCHARIVILATHIRUVANANTHAPURAM PUTHEN VEEDU, THIRUVANANTHAP 8 602 APPUKUTTAN ASARI K ASARI 18000 KOTTUKAL, KOTTUKAL.P.O, URAM VRA38,THIRUVANANTHAPURAM VAYALARIKATHUVEEDU, THIRUVANANTHAP 9 305 ARUNACHALAM ACHARY M THATTAN 14700 KESAVADASAPURAM, URAM PANAYATHUPATTOM,THIRUVANANTHAPURAM VEEDU , MUTTAPPALAM 695004 , THIRUVANANTHAP VISWAKARAMA/V 10 904 ASOKAN ASARI 18000 PERUNGUZHI , TRIVANDRUM URAM ISWAKARMAS AYYAPPA NIVAS , NEAR GOVT UPS , (OPPT TO THIRUVANANTHAP 11 3236 AYYAPPAN ACHARI M THATTAN -

Progressive Mine Closure Plan

UNDER RULE 53 & 5A OF I<MMC RULES, 2015 FOR KERALA STATE ;-"i..,):F,: -;' , ;'1'.,.:?.i : a-= .,. i,.' lr C E Rf l,i ICATES u*"a?h u'<u-a auftr'l lllllf(*'lcr q.2-2 r-2.1 ntr:! t jt,, t . aso,;ooo.-"o. m h" 2 thol y.u w ll ro N j€ Mine sor6t olbo5c nfE.fudue ,!ci li$ hdudho !o; This h to cdti6, that rhe MininA PLm in.luding P.osEssve Quariy Closure Plm ol G.miie Buildins stone quarry ol A. Mohmned Bashrtr, Mylack8r, 'rhempakata veedu, venjdmmdu P O, Nelldad, Thiruymdthapum exiends over an ar€a ol 2.1504 Ha, snuated in sy. No 91/3, 9l12 2. 9ll2.1, e1l2 3, & ell2pi BLock No. 22 or Puuupara viuase, Nedummsad 'r31xk ol Thiruvm{thapuru District Kerala 3 & 5a o{ KMMCR 2015 by Mr. v,I.Ra, ceologisr & RoP, the D.partmmr ot Mining dd ceolos/, to mal<e dy lurther .orespondence .esaiti.g dy @rreciion ol the MininE Pld with the said Recognised Qualified Pelson ar his addiess Eiven below: s ua, ql La R. c, ha.d oa, ^., ..^d :!k ols@tQa&tLcom We hereby udedake that a 11 modilications / xpdating as rode in rhe said scheme ol Miniry by the said Recqni$d Qualii,ine Pe.son be deemed to have been made with our knowled8e dd consmt and shall be accepable on us dd bindi,g in all ,.h- -". CERTIFICAfE It is efrified that the Pmeressive Qu.rry Closure Hm of Cranite Building Stone Quury ol Mylacksl, 'Ihmpakala Veedu, Vmjdm@du .P o, Nellmad, thiruvmathapurm, area ol 2.150.1 Ha, siiusted in Re survey.