Those Weren't the Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2011 Smithsonian Exhibit Tour Key Ingredients

THE MAGAZINE OF THE OKLAHOMA HUMANITIES COUNCIL Fall 2011 Smithsonian Exhibit Tour Key Ingredients: America By Food After 9/11 Featuring Public Radio’s Krista Tippett OHC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Ann Neal, Chair Miami UMANITIES Dr. Benjamin Alpers, Vice Chair/Secretary Volume IV, Issue No. 3 Fall 2011 University of Oklahoma John Martin, Treasurer Ann Thompson Executive Director Enid Carla Walker Editor, Oklahoma HUMANITIES Lona Barrick Director of Communications Ada David Pettyjohn Assistant Director Dr. Mary Brodnax Traci Jinkens Marketing & Development Director University of Central Oklahoma Kelly Elsey Administrative Coordinator Dr. William Bryans Charles White Fiscal Officer Oklahoma State University Manda Overturf Program Officer Judy Cawthon Edmond Beverly Davis Oklahoma HUMANITIES is published three times per year: January, May, and September by the Oklahoma Oklahoma City Humanities Council (OHC), 428 W. California Ave., Ste. 270, Oklahoma City, OK 73102. OHC is an independent, Lynn McIntosh nonprofit organization whose mission is to promote meaningful public engagement with the humanities— Ardmore disciplines such as history, literature, film studies, ethics, and philosophy. As the state partner for the National Endowment for the Humanities, OHC provides cultural opportunities for Oklahomans of all ages. With a focus on Senator Judy Eason McIntyre Tulsa K-12 education and community building, OHC engages people in their own communities, stimulating discussion and helping them explore the wider world of human experience. Mary Ellen Meredith Oklahoma City The opinions expressed in Oklahoma HUMANITIES are those of the authors. Any views, findings, conclusions, or Lou Nelson recommendations expressed in the magazine do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment Guymon for the Humanities, the Oklahoma Humanities Council, its Board of Trustees, staff, or donors. -

Chapter One: Postwar Resentment and the Invention of Middle America 10

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Timothy Melley, Director ________________________________________ C. Barry Chabot, Reader ________________________________________ Whitney Womack Smith, Reader ________________________________________ Marguerite S. Shaffer, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT TALES FROM THE SILENT MAJORITY: CONSERVATIVE POPULISM AND THE INVENTION OF MIDDLE AMERICA by Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff In this dissertation I show how the conservative movement lured the white working class out of the Democratic New Deal Coalition and into the Republican Majority. I argue that this political transformation was accomplished in part by what I call the "invention" of Middle America. Using such cultural representations as mainstream print media, literature, and film, conservatives successfully exploited what came to be known as the Social Issue and constructed "Liberalism" as effeminate, impractical, and elitist. Chapter One charts the rise of conservative populism and Middle America against the backdrop of 1960s social upheaval. I stress the importance of backlash and resentment to Richard Nixon's ascendancy to the Presidency, describe strategies employed by the conservative movement to win majority status for the GOP, and explore the conflict between this goal and the will to ideological purity. In Chapter Two I read Rabbit Redux as John Updike's attempt to model the racial education of a conservative Middle American, Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom, in "teach-in" scenes that reflect the conflict between the social conservative and Eastern Liberal within the author's psyche. I conclude that this conflict undermines the project and, despite laudable intentions, Updike perpetuates caricatures of the Left and hastens Middle America's rejection of Liberalism. -

The Presidents Desk: an Alt-History of the United States Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PRESIDENTS DESK: AN ALT-HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Shaun Micallef | 288 pages | 01 Nov 2015 | HARDIE GRANT BOOKS | 9781743790830 | English | South Yarra, Australia The Presidents Desk: An Alt-History of the United States PDF Book Kennedy read the plaque on the desk, realized its significance in naval history, and directed that it be placed in the Oval Office. All were acquitted. Owen, Roderic. Robert McNamara. Kennedy Finds a Historical Desk for President. Wikimedia Commons. By the time they were ready to leave, both Assistance and Pioneer had broken free and had traveled 45 miles South in the Wellington Channel until they were only a few miles from Beechey Island. The Resolute Desk is a massive oak desk closely associated with presidents of the United States due to its prominent placement in the Oval Office. John F. Assassination timeline reactions in popular culture State funeral Riderless horse attending dignitaries Gravesite and Eternal Flame. This made no difference to Belcher who was simply desperate to go home. The Resolute Desk, for a time, was on display in the Smithsonian's American Museum of American History, as part of an exhibit on the presidency. Kennedy Administration. Never quite sure where the truths, rumour and innuendo finish and the made up stuff begins, I'm fairly sure that Bess Truman wasn't an alien? It took nearly a month to reach England, and the American crew found itself in peril from an intense storm just as it neared Portsmouth harbor. After Resolute was broken up, Queen Victoria asked for several desks to be built from her timbers. -

The Vice President's Room

THE VICE PRESIDENT’S ROOM THE VICE PRESIDENT’S ROOM Historical Highlights The United States Constitution designates the vice president of the United States to serve as president of the Senate and to cast the tie-breaking vote in the case of a deadlock. To carry out these duties, the vice president has long had an office in the Capitol Building, just outside the Senate chamber. Earliest known photographic view of the room, c. 1870 Due to lack of space in the Capitol’s old Senate wing, early vice presidents often shared their room with the president. Following the 1850s extension of the building, the Senate formally set aside a room for the vice president’s exclusive use. John Breckinridge of Kentucky was the first to occupy the new Vice President’s Room (S–214), after he gavelled the Senate into session in its new chamber in 1859. Over the years, S–214 has provided a convenient place for the vice president to conduct business while at the Capitol. Until the Russell Senate Office Building opened in 1909, the room was the only space in the city assigned to the vice presi- dent, and it served as the sole working office for such men as Hannibal Hamlin, Chester Alan Arthur, and Theodore Roosevelt. Death of Henry Wilson, 1875 Several notable and poignant events have occurred in the Vice President’s Room over the years. In 1875 Henry Wilson, Ulysses S. Grant’s vice president, died in the room after suffering a stroke. Six years later, following President James Garfield’s assassination, Vice President Chester Arthur took the oath of office here as president. -

Download Here

The Official Newsletter of the Asbury Park Historical Society Where the Past JOIN UP OR Meets the Future RENEW YOUR © R. Sternesky _____________________________________________________MEMBERSHIP! See Page 6 for Details! _____________________________________________________© 2018 Asbury Park Historical Society WINTER 2018 Here’s to the new year...and the best of the past! Mark your calendar! Our annual reorganization meeting is Thursday, January 18 It’s the first and biggest forum of the year for the nonprofit, all-volunteer organization whose motto is “Where the Past Meets the Future” — and on the evening of January 18, the Asbury Park Historical Society invites all members of the community to our annual Reorganization Meeting. Hosted in the city’s historic Public Library at First and Grand Avenues, the 7 p.m. program will cast our customary detailed look at an aspect of Asbury Park’s richly storied past, with a special presentation on the Society’s effort to preserve three of our city’s historic monuments. There’s also an eye on the future, with updates on the ongoing work at our historic Crane House headquarters — as well as a pre- The desk that President Wilson used in his Asbury view of APHS activities in the months ahead, plus new info Park summer headquarters remains on display at the on membership policy and a welcome message from the Ocean Township Historical Society through June. Board of Trustees. Complimentary refreshments will be served, so join your fellow APHS members for our first A “seat of government” for a U.S. “night to remember” of the new year! President, in Asbury Park He was a native son of Virginia when he was born in 1856 — but Thomas Woodrow Wilson can be said to be New Jersey’s most significant contribution to the timeline of the nation’s highest elected office. -

Introduction Rick Perlstein

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Rick Perlstein I In the fall of 1967 Richard Nixon, reintroducing himself to the public for his second run for the presidency of the United States, published two magazine articles simultaneously. The first ran in the distinguished quarterly Foreign Affairs, the re- view of the Council of Foreign Relations. “Asia after Viet Nam” was sweeping, scholarly, and high-minded, couched in the chessboard abstrac- tions of strategic studies. The intended audience, in whose language it spoke, was the nation’s elite, and liberal-leaning, opinion-makers. It argued for the diplomatic “long view” toward the nation, China, that he had spoken of only in terms of red- baiting demagoguery in the past: “we simply can- not afford to leave China forever outside the fam- ily of nations,” he wrote. This was the height of foreign policy sophistication, the kind of thing one heard in Ivy League faculty lounges and Brookings Institution seminars. For Nixon, the conclusion was the product of years of quiet travel, study, and reflection that his long stretch in the political wil- derness, since losing the California governor’s race in 1962, had liberated him to carry out. It bore no relation to the kind of rip-roaring, elite- baiting things he usually said about Communists For general queries, contact [email protected] © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. -

PROLOGUE August 9, 1974 at Midnight on August 8, 1974

PROLOGUE August 9, 1974 At midnight on August 8, 1974, Stephen Bull, the personal assistant to the President of the United States, walked into the President's office, the Oval Office. It was quiet and dark in the West Wing of the White House. The television cameras were gone. The correspondents and the technicians had folded up their equipment and left after the thirty-seventh president, Richard Milhous Nixon, had announced, two hours before, that he would resign the office at noon on August 9. Bull decided not to turn on the lights. He could see enough in the dim light from the hallway. He went in, picked up Nixon's briefcase, put it near the doorway, and then began to pack away the things on the desk. The President was flying home to California the next day, and Bull decided to put everything on the desk there, just the way it was here, as if nothing had happened. He began with Nixon's reading glasses and a photograph of the President's two daughters, Tricia and Julie. As he picked up the appointment book, he bumped against the silver cigarette case the girls had given the President on the day he was inaugurated. The case was knocked off the desk onto the rug. It opened and the music box inside began to play its tinny tune, "Hail to the Chief." Later, the President's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, who had spent twenty-three years with him in good times and bad, and an assistant named Marge Acker came in and began emptying the drawers into cardboard boxes. -

The President's Conservatives: Richard Nixon and the American Conservative Movement

ALL THE PRESIDENT'S CONSERVATIVES: RICHARD NIXON AND THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE MOVEMENT. David Sarias Rodriguez Department of History University of Sheffield Submitted for the degree of PhD October 2010 ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation exammes the relationship between the American conservative movement and Richard Nixon between the late 1940s and the Watergate scandal, with a particular emphasis on the latter's presidency. It complements the sizeable bodies ofliterature about both Nixon himself and American conservatism, shedding new light on the former's role in the collapse of the post-1945 liberal consensus. This thesis emphasises the part played by Nixon in the slow march of American conservatism from the political margins in the immediate post-war years to the centre of national politics by the late 1960s. The American conservative movement is treated as a diverse epistemic community made up of six distinct sub-groupings - National Review conservatives, Southern conservatives, classical liberals, neoconservatives, American Enterprise Institute conservatives and the 'Young Turks' of the New Right - which, although philosophically and behaviourally autonomous, remained intimately associated under the overall leadership of the intellectuals who operated from the National Review. Although for nearly three decades Richard Nixon and American conservatives endured each other in a mutually frustrating and yet seemingly unbreakable relationship, Nixon never became a fully-fledged member of the movement. Yet, from the days of Alger Hiss to those of the' Silent Majority', he remained the political actor best able to articulate and manipulate the conservative canon into a populist, electorally successful message. During his presidency, the administration's behaviour played a crucial role - even if not always deliberately - in the momentous transformation of the conservative movement into a more diverse, better-organised, modernised and more efficient political force. -

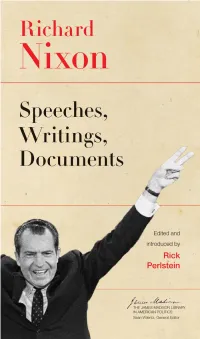

Richard Nixon: Speeches, Writings, Documents, Edited and Introduced by Rick Perlstein Richard Nixon Speeches, Writings, Documents

Richard Nixon THE JAMES MADISON LIBRARY IN AMERICAN POLITICS The James Madison Library in American Politics of the Princeton University Press is devoted to reviving important American political writings of the recent and distant past. American politics has pro- duced an abundance of important works—proclaiming ideas, de- scribing candidates, explaining the inner workings of government, and analyzing political campaigns. This literature includes partisan and philosophical manifestos, pamphlets of practical political theory, muckraking expose´s, autobiographies, on-the-scene reportage, and more. The James Madison Library issues fresh editions of both clas- sic and now-neglected titles that helped shape the American political landscape. Up-to-date commentaries in each volume by leading scholars, journalists, and political figures make the books accessible to modern readers. The Conscience of a Conservative by Barry M. Goldwater The New Industrial State by John Kenneth Galbraith Liberty and the News by Walter Lippmann The Politics of Hope and The Bitter Heritage: American Liberalism in the 1960s by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Richard Nixon: Speeches, Writings, Documents, edited and introduced by Rick Perlstein Richard Nixon Speeches, Writings, Documents Edited and introduced by Rick Perlstein PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright © 2008 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nixon, Richard M. (Richard Milhous), 1913–1994. [Selections. 2008] Richard Nixon : speeches, writings, documents /edited and introduced by Rick Perlstein. p. cm. — (The James Madison Library in American politics) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

What West Wrought the Graduate College Turns 100: a Photo Essay

NAJLA SAID ’96 TAX!EXEMPT STATUS NEW IMAGING TOOL, WRITES HER ROLE CHALLENGED NEW REVELATIONS PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY What West Wrought The Graduate College Turns 100: A Photo Essay SEPTEMBER 18, 2013 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0918_cover REV1.indd 1 9/3/13 5:30 PM Art by renowned illustrator Isabelle Arsenault. RENOWNED GUIDANCE We have served families for generations, offering the counsel and advice needed to handle even the most complex wealth management needs. To learn how we can apply our knowledge and experience to help preserve your family’s legacy, call Mark Graham at 302-651-1665, email [email protected], or visit wilmingtontrust.com. FIDUCIARY SERVICES | WEALTH PLANNING | INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT | PRIVATE BANKING ©2013 Wilmington Trust Corporation. An M&T Company. wt007751 IVY_MG_M.indd 1 6/25/13 4:13 PM 7751 IVY_MG 8.125” x 10.5” 130906_WilmingtonTrust.indd 1 7/16/13 1:45 PM September 18, 2013 Volume 114, Number 1 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 Adam Maloof sits at his new grinding INBOX 3 machine, named GIRI, page 28. FROM THE EDITOR 5 ON THE CAMPUS 11 Lawsuit challenges tax- exempt status Annual Giving results Construction update Grafton challenge Student Dispatch: Sustainable fashion Students make documentary "lm SPORTS: Football preview Summer softball LIFE OF THE MIND 27 The psychology of scarcity Gregor Creative destruction The amazing fruit !y Research shorts PRINCETONIANS 45 Alumna’s research leads to reparations agreement Laura Ray ’84 *91: Polar-robot designer A. Scott Berg ’71 on Woodrow Wilson Reading Room: Aaron Hirsh ’94 CLASS NOTES 52 Searching for Palestine 34 Away From the Horde 38 MEMORIALS 71 Najla Said ’96 has a famous last name, but A photographic celebration of the Graduate CLASSIFIEDS 78 she is writing her own script, determined that College, which turns 100 this year. -

A Comparison of Government-Sponsored Integration of Design

A COMPARISON OF GOVERNMENT-SPONSORED INTEGRATION OF DESIGN AND SOCIETY IN THE UNITED STATES AND THE NETHERLANDS by Dillon R. Sorensen, B.S. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts with a Major in Communication Design May 2021 Committee Members: Claudia Röschmann, Chair Jeffrey Lieber Dimitry Tetin COPYRIGHT by Dillon R. Sorensen 2021 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Dillon R. Sorensen, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My utmost gratitude is extended to my thesis chair Claudia Röschmann. Thank you for teaching me about the power of typography and exposing me to contemporary European design. The trip that you led in the spring of 2019 inspired this thesis and will remain a cherished memory for years to come. Thank you to my other committee members, Jeffrey Lieber and Dimitry Tetin. I am deeply inspired by your work as designers and thinkers. Your intellectual rigor was essential to the completion of this paper. To all of the MFA faculty at Texas State University who I took a class with over the past five years: I have learned something from each and every one of you. -

Book Reviews

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 42 Issue 1 Article 13 3-2004 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (2004) "Book Reviews," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 42 : Iss. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol42/iss1/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 60 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION BOOK REVIEWS We Came Naked and Barefoot: The Journey ofCaheza de Vaca Across North America, Alex D. Krieger and editor, Margery H. Krieger (University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819. Austin, TX 78713-7819) 2002. Contents. Maps. Appendices. References. Index. P. 318. $39.95. Hardcover. In 1536 Cabeza de Vaca entered Mexico City after a harrowing journey that included six years in captivity among various indigenous groups. A survivor of the catastrophic Narvaez Expedition (1527) he returned with stories resulting in subsequent Spanish excursions searching for gold as well as rich descriptions of the natives and their way of life. The problem to arise from this was that de Vaca included valuable ethnographies of such groups in his account but he did not know where he was, making the identification of such groups difficult for modern scholars. In his dissertation, the late Alex D. Krieger utilized his personal knowledge of the geography and environment ofTexas to trace the route most likely traveled by de Vaca and his companions.