Making Collage Can Be a Symbolic Art, Like Life Itself - a Tangle Unravelled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eduardo Paolozzi Born Edinburgh, Scotland. 1924 Resident London

Eduardo Paolozzi Born Edinburgh, Scotland. 1924 ResidentLondon Eduardo Paolozziwas visited in London by MT in Octo- really preparedto offer him the kind of freedom or the ber, 1968. When A & T was describedto Paolozzion degreeof accessto their personneland hardwarethat he that occasion,he respondedby expressinginterest in required--thoughthe corporation was equipped techni- working with computers. His work at that time was cally to deal with whatever demandsthe artist might involved in computer-generatedimagery, and thus it was make in the areaof computer graphics.On the evening natural that he should wish to developthese ideas. In after this encounter,Paolozzi telephoned Jane Living- Paolozzi'sletter to us of October 30, he spoke about the ston from his hotel and explainedto her that he saw no areashe visualizedpursuing: point in touring the San Josefacility or bothering It is my intention of bringing a portfolio of schemes further with lBM. Paolozzithen visited Wyle Laborator- in connection with the Los Angelesshow. These ies.He was interviewedby the company's president, schemesare an extension of work concerningimages Frank Wyle [1] ; Gail Scott wrote the following memo and words (ref: the Berkeleycatalogue; Christopher recountingthis event and later discussion: Finch's book Art and Objectsl. You may realizethat I did a certain amount of com- puter researchwhile at Berkeley,but the Art Depart- ment there was unable to extend any of these ideas- which certainly could be realizedwithin the frame- work that we discussedin London during your visit. At the moment, I have an assistantworking on colour mosaicsand endlesspermutations on the grid pattern. This is accordingto my interpretation of current computer literature and can be used in connection with sound experiments.Also the reverse,I under- stand, is possible;which is, soundscan be usedto create patterns. -

Lynn Chadwick

PANGOLIN for immediate release For further information contact: Georgina Trower: 020 7520 1480 [email protected] LYNN CHADWICK: THE COUPLE 12 January - 26th February 2011 Lynn chadwick Maquette IV Diamond 1984, Bronze Lynn Chadwick: The Couple is the largest exhibition of its kind to concentrate on one of the most prevalent themes of Chadwick’s artistic career: ‘The Couple’. Exploring the most intimate of human unions the exhibition will include works spanning over 40 years, from seminal early pieces such as Teddy Boy and Girl LONDON and Dancers through to his instantly recognisable seated couples of the late 80s and early 90s. Lynn Chadwick is one of the most eminent British sculptors of the 20th century, and an important addition to any modern art collection. Chadwick first came to prominence in 1952 when he was included in the British Council’s New Aspects of British Sculpture exhibition for the XXVI Venice Biennale alongside Kenneth Kings Place Armitage, Reg Butler, Henry Moore and Eduardo Paolozzi. The following 90 York Way London year he was one of twelve semi-finalists for the Unknown Political Prisoner N1 9AG International Sculpture Competition and at the 1956 Venice Biennale he won the International Sculpture Prize, beating Giacometti. 020 7520 1480 Lynn Chadwick Maquette II Watchers V 1967, Bronze Pangolin London has a particularly unique relationship with Lynn Chadwick which dates back to 1983 when owners Rungwe Kingdon and Claude Koenig were appointed his founders and assistants. They went on to set up their own foundry, Pangolin Editions, which is now the largest in europe and which Pangolin London are directly affiliated to. -

Eduardo Paolozzi 16 February – 14 May 2017 Media View: 15 February 2017, 10:00 – 13:00

Eduardo Paolozzi 16 February – 14 May 2017 Media View: 15 February 2017, 10:00 – 13:00 The Whitechapel Gallery announces the first major retrospective of Eduardo Paolozzi in 40 years from 16 February – 14 May 2017 Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005) was one of the most innovative and irreverent British artists of the 20th century. Considered the ‘godfather of Pop Art’, his powerful collages, sculptures and prints challenged artistic convention from the 1950s ‘Geometry of Fear’ all the way through the Swinging Sixties and on to the advent of ‘Cool Britannia’ in the 1990s. From his post-War bronzes to revolutionary screen-prints, collages and bold textile designs, this first major retrospective since 1971 aims to reassess Paolozzi’s varied and experimental artistic approach, and highlight the relevance of his work for artists today. Spanning five decades and featuring more than 250 works from public and private collections the exhibition focuses on the artist's radical explorations of material and form, processes and technologies, and consistent rejection of aesthetic convention throughout his career. Rarely exhibited drawings, maquettes and sculptures will shed new light on overlooked or lesser known aspects of his work. The exhibition is presented in four chronological sections and begins with Paolozzi’s groundbreaking early brutalist concrete sculptures including Seagull and Fish (1946), Fish (1946-7) and Blue Fisherman (1946) reunited for the first time since Paolozzi’s debut London exhibitions in 1947. Material from the artist’s influential performative lecture, Bunk! (1952) and examples of textile, fashion and design work including the highly patterned Horrockses Cocktail Dress (1953), are also on display. -

William Turnbull William Turnbull

11 Cork Street tel +44 (0)20 7851 2200 mail@waddington -galleries.com waddington galleries London W1S 3LT fax +44 (0)20 7734 4146 www.waddington-galleries.com PRESS RELEASE William Turnbull Sculpture & Paintings from 1946 to 1962 31st January - 24th February 2007 Monday – Friday 10am-6pm Saturday 10am-1.30pm Mask, 1947, bronze, edition of 4 15 1/2 x 91/2 x 5/8 in / 39.5 x 24 x 1.5 cm “Monumentality is a value and not a dimension” 1 Waddington Galleries are pleased to announce an exhibition of sculpture and paintings by William Turnbull, concentrating on the years 1946 –1962. The earliest work in the exhibition is Mask 1946 . Originally conceived in concrete and string it was made whilst Turnbull was still a student at the Slade, London. In 1948 he transferred his grant to study in Paris, there meeting Brancusi, Leger and becoming friends with Hélion and Giacometti. In 1950, having moved back to London, he made Horse a linear dissection of three-dimensional space that stands poised without a base. This bronze has a direct relationship to the paintings of Heads and Figure from 1956, their motifs built from thick interlinking bars of monochromatic impasto. To create Figure 1955 corrugated cardboard was pressed into wet plaster making the column-like figure appear fashioned from seams of strata, its elemental shape revealed by lines of erosion - the fluid plaster fossilized into bronze, creating an aura of permanence and stillness. Screwhead 1957 is a similar upturned-T composition whose forms originated from a chocolate grinder and grandfather clock but again, through Turnbull’s economy of expression, suggests a motionless totemic figure. -

Use the Questions and Activities to Explore the Art with Your Families

at Salisbury Cathedral For nearly eight hundred years, Salisbury Cathedral has been a significant holy building, a special place for millions of visitors and Christians. At the heart of the Cathedral’s life is its worship. Take a virtual tour around the Cathedral’s 2020 Art Exhibition ‘Celebrating 800 years of Spirit and Endeavour’ located both inside the building and outside on the Cathedral lawns. This special art exhibition aims to capture the spirit of the medieval people who came together in faith to build Salisbury Cathedral. Through their hard work and endeavour, we have this incredible building today which is evidence of the remarkable vision and creativity of these ordinary people. Use the questions and activities to explore the art with your families. Post photos of your creations and pictures inspired by the exhibition on Twitter using #spiritandendeavour Curated by Jacquiline Creswell, Salisbury Cathedral’s Visual Arts Adviser. What’s a curator, you ask? A person who creates exhibitions by collecting works of art or objects together to tell a story. Death of a Working Hero by Grayson Perry This tapestry by Grayson Perry is about the mine workers in Durham. It prompts us to remember the ordinary people who worked to build Salisbury Cathedral and reflect on their legacy. • How do you think the medieval stone masons and carpenters who built Salisbury Cathedral would like to be remembered? Time and Place by Bruce Munro The effect of light is an important part of Bruce Monro’s work. For this work, Munro used pixilated photographs of Salisbury Cathedral taken during the 800th anniversary year. -

Twelve Minute Films by Edward Paolozzi to Be Screened at MOMA

he Museum of Modern Art 11 No. 55 est 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modemart Monday, October 5, I96I+ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE HISTORY OF NOTHING, a 12-minute collage film made by the contemporary British, artist, Eduardo Paolozzi, will be screened at The Museum of Modern Art daily at 2:15 p.m., October 5 through November 10. Paolozzi points out that "this film has no technical innovations; relying mainly on its content, conveyed through elements of surprise — unexpected feelings and strange juxtapositions of image and situation. The language of orthodox surrealism is used in some cases, for example, a collage of machines and objects in rooms. (These collages were done in Hamburg during the period between April i960 and April I96I.) The varied still material is in itself of considerable interest. Certain items have been selected and reinterpreted into screen prints.11 Included are plates from a perforated metal catalogue; views of New York, Sao Paulo and San Remo; a clown and an electronic arm. The accompanying semi-synchronized sound track is drawn from records of church bells, altered jazz, African drums, locomotives, airplanes, etc. The well-known art critic, Dore Ashton, comments that Paolozzi "builds the tex ture of the film in the same way he builds his sculptures. Small details are repeated in slightly different forms throughout. Dominant images, such as an old-walled Italian town perched on a cliff and metamorphosed into a parody of modern war mammoth, are presented at regular intervals, fitted into new circumstances until toward the end they register as parts of a cataclysmic event." The film presented in conjunction with the current Museum of Modern Art exhibi tion of prints and sculpture by Paolozzi, was made in the winter of I96I at the Royal College of Art in London. -

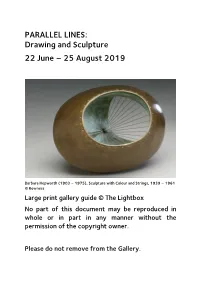

PARALLEL LINES: Drawing and Sculpture 22 June – 25 August 2019

PARALLEL LINES: Drawing and Sculpture 22 June – 25 August 2019 Barbara Hepworth (1903 – 1975), Sculpture with Colour and Strings, 1939 – 1961 © Bowness Large print gallery guide © The Lightbox No part of this document may be reproduced in whole or in part in any manner without the permission of the copyright owner. Please do not remove from the Gallery. The Ingram Collection Working in partnership with galleries, innovative spaces and new artistic talent, The Ingram Collection brings art to the widest possible audience. The Ingram Collection is one of the largest and most significant publicly accessible collections of Modern British Art in the UK, available to all through a programme of public loans and exhibitions. Founded in 2002 by serial entrepreneur and philanthropist Chris Ingram, the collection now spans over 100 years of British art and includes over 600 artworks. More than 400 of these are by some of the most important British artists of the twentieth century, amongst them Edward Burra, Lynn Chadwick, Elisabeth Frink, Barbara Hepworth and Eduardo Paolozzi. The main focus of the collection is on the art movements that developed in the early and middle decades of the twentieth century, and there is a particularly strong and in-depth holding of British sculpture. The Ingram Collection also holds a growing number of works by young and emerging artists, and in 2016 established its Young Contemporary Talent Purchase Prize in order to celebrate and support the work and early careers of UK art school graduates. The Royal Society of Sculptors The Royal Society of Sculptors is an artist led membership organisation. -

'Reforming Academicians', Sculptors of the Royal Academy of Arts, C

‘Reforming Academicians’, Sculptors of the Royal Academy of Arts, c.1948-1959 by Melanie Veasey Doctoral Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University, September 2018. © Melanie Veasey 2018. For Martin The virtue of the Royal Academy today is that it is a body of men freer than many from the insidious pressures of fashion, who stand somewhat apart from the new and already too powerful ‘establishment’.1 John Rothenstein (1966) 1 Rothenstein, John. Brave Day Hideous Night. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1966, 216. Abstract Page 7 Abstract Post-war sculpture created by members of the Royal Academy of Arts was seemingly marginalised by Keynesian state patronage which privileged a new generation of avant-garde sculptors. This thesis considers whether selected Academicians (Siegfried Charoux, Frank Dobson, Maurice Lambert, Alfred Machin, John Skeaping and Charles Wheeler) variously engaged with pedagogy, community, exhibition practice and sculpture for the state, to access ascendant state patronage. Chapter One, ‘The Post-war Expansion of State Patronage’, investigates the existing and shifting parameters of patronage of the visual arts and specifically analyses how this was manifest through innovative temporary sculpture exhibitions. Chapter Two, ‘The Royal Academy Sculpture School’, examines the reasons why the Academicians maintained a conventional fine arts programme of study, in contrast to that of industrial design imposed by Government upon state art institutions for reasons of economic contribution. This chapter also analyses the role of the art-Master including the influence of émigré teachers, prospects for women sculpture students and the post-war scarcity of resources which inspired the use of new materials and techniques. -

New Exhibit of Eduardo Paolozzi

iff he Museum of Modern Art No. k7 FOR RELEASE: N-.t. New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modemart Monday, September 21, 19&J- PRESS PREVIEW: Friday, September 18, 1964 11 a.m. - k p.m. Four recent large aluminum sculptures by the UO-year-old British artist Eduardo Paolozzi, will be on view along with a dozen related prints and a book at The Museum of Modern Art from September 21 through November 10. The exhibition is directed by Peter Selz, Curator, Painting and Sculpture Exhibitions. The sculpture and prints date from the *60s when Paolozzirs work took a new direction and he began to make welded "engineered" constructions combining actual machine parts with invented shapes. "In the fifties Paolozzi established his reputation by making archaic-looking human figures, whose heavy textures he cast from clockworks, locks, forks, parts of automobiles and bombsights," Peter Selz points out in the wall label for the exhibi tion. "In these pieces he was actually creating collage sculptures cast from ready- made s. "The present large robot-like structures are assembled from industrially made aluminum castings by the artist working hand in hand with engineers. These mechan ized, precise but functionless inventions allude plastically to our industrialized and automated civilization. His new sculpture, his silk screen prints, his collages, but book and film are not only superb formal achievements in their own right,/they also demonstrate that a human and intuitive approach is still possible in a cybernetic world. Significantly, he invokes the name of Ludwig Wittgenstein, the influential Cambridge philosopher, who inspired both logical positivism and the linauistic or analytic movement in recent thought." The four sculptures on view are: Diana as an Engine II (1962), The World Divides Into Facts (1963), Lotus (1964), and Wittgenstein at Cassino I (1963). -

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS' LIVES Lynn Chadwick

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS’ LIVES Lynn Chadwick Interviewed by Cathy Courtney C466/28 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] This transcript is accessible via the British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings website. Visit http://sounds.bl.uk for further information about the interview. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk IMPORTANT Access to this interview and transcript is for private research only. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ( [email protected] ) © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C466/28/01-11 Digitised from cassette originals Collection title: Artists’ Lives Interviewee’s surname: Chadwick Title: Interviewee’s forename: Lynn Sex: male Occupation: Artist Dates: 1914 – 2003 Dates of recording: 1995.04.04, 1995.04.20, 1995.05.16 Location of interview: Lyppiatt Park Name of interviewer: Cathy Courtney Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 Recording format: D60 Cassette F numbers of playback cassettes: F4555 – F4565 Total no. -

Eduardo Paolozzi. Lots of Pictures – Lots of Fun 09.02.–28.05.2018

Eduardo Paolozzi. Lots of Pictures – Lots of Fun 09.02.–28.05.2018 PRESS KIT CONTENTS Press release Biography Eduardo Paolozzi Exhibition texts Catalogue Education programme Press images WWW.BERLINISCHEGALERIE.DE Eduardo Paolozzi. Lots of Pictures – Lots of Fun 09.02.–28.05.2018 PRESS CONFERENCE 08.02.2018, 11 am (in German) Welcome reception and introduction to the exhibition and accompanying catalogue Dr. Thomas Köhler, Director Berlinische Galerie Introduction to the exhibition Dr. Stefanie Heckmann, head of the visual art collection and curator of the exhibition Followed by a tour to the exhibition with Dr. Stefanie Heckmann and Daniel F. Herrmann, initiator and curator of the Whitechapel Gallery exhibition, who has been appointed curator of special projects at the National Gallery London OPENING 08.02.2018, 7 pm (in German) Speakers: Dr. Thomas Köhler, Director Berlinische Galerie Sir Sebastian Wood, British ambassador in Germany Dr. Stefanie Heckmann, Head of Department Fine Arts, curator of the exhibition Followed by music by DJ Cambel Nomi The admission to the event starts at 6 pm. WWW.BERLINISCHEGALERIE.DE BERLINISCHE GALERIE LANDESMUSEUM FÜR MODERNE ALTE JAKOBSTRASSE 124-128 FON +49 (0) 30 –789 02–600 KUNST, FOTOGRAFIE UND ARCHITEKTUR 10969 BERLIN FAX +49 (0) 30 –789 02–700 STIFTUNG ÖFFENTLICHEN RECHTS POSTFACH 610355 – 10926 BERLIN [email protected] PRESS RELEASE Ulrike Andres Head of Communications and Education Tel. +49 (0)30 789 02-829 [email protected] Contact: Bureau N Gudrun Landl Tel. +49 (0)30 627 36102 [email protected] Berlin, February 2018 Eduardo Paolozzi Lots of Pictures – Lots of Fun 09.02.–28.05.2018 Press conference: 08.02.2018, 11 AM, Opening: 08.02.2018, 7 PM, Children’s Opening: 11.02.2018, 3–5 PM Born in Edinburgh, the sculptor and graphic artist Eduardo Paolozzi (1924‒2005) was one of the most innovative and irreverent artists of the British postwar period. -

Gagosian Gallery

Post Magazine July 9, 2016 GAGOSIAN GALLERY Gagosian Hong Kong shows first paintings of much collected sculptor Thomas Houseago Yorkshire-born, Los Angeles-based artist’s paintings blend futurism, cubism and modernism. Knowledge of Houseago’s sculpture, inspired by primitivism of African and Oceanic art, provides a better understanding of exhibition John Batten Thomas Houseago’s Psychedelic Brothers- Drawn Paintings exhibition. Picture: Courtesy of Thomas Houseago and Gagosian Gallery The paintings of Yorkshire-born, Los Angeles-based Thomas Houseago glide through a blend of 20th-century futurism, cubism and modernism. These are accomplished and informative studies accurately described in the title of the exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery. Despite a carefully unfinished quality, the nine large paintings exhibited as “Thomas Houseago: Psychedelic Brothers – Drawn Paintings” are not rapid-fire drawings or sketches, but fully resolved works in elaborate layers of pastel, crayon, pencils, oil and acrylic on canvas, particularly the complex “Psychedelic Brother III (blue architecture) (2016)”. Houseago is a figurative sculptor who studied at Central Saint Martins, in London, and at De Ateliers, in Amsterdam, and lived in Brussels before relocating to LA in 2003. Sought after by collectors, his sculptures are generally large and completed with a team of assistants in an extensive warehouse in LA. His bronze pieces are cast in foundries across the United States. At the 2011 Venice Biennale, his “L’homme pressé (2011-2012)”, a huge bronze of a man in a hurry, was displayed on the Grand Canal, outside the Venice museum of Christie’s owner François-Henri Pinault, as part of his collection.