Downloaded 4.0 License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A. Information Concerning the Personality to Be Celebrated

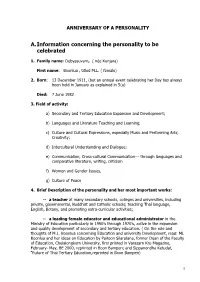

ANNIVERSARY OF A PERSONALITY A. Information concerning the personality to be celebrated 1. Family name: Debyasuvarn, ( née Kunjara) First name: Boonlua , titled M.L. ( female) 2. Born: 13 December 1911, (but an annual event celebrating her Day has always been held in January as explained in 5(a) Died: 7 June 1982 3. Field of activity: a) Secondary and Tertiary Education Expansion and Development; b) Languages and Literature Teaching and Learning; c) Culture and Cultural Expressions, especially Music and Performing Arts; Creativity; d) Intercultural Understanding and Dialogue; e) Communication, Cross-cultural Communication--- through languages and comparative literature, writing, criticism f) Women and Gender Issues, g) Culture of Peace 4. Brief Description of the personality and her most important works: -- a teacher at many secondary schools, colleges and universities, including private, governmental, Buddhist and Catholic schools; teaching Thai language, English, Botany, and promoting extra-curricular activities; -- a leading female educator and educational administrator in the Ministry of Education particularly in 1950’s through 1970’s, active in the expansion and quality development of secondary and tertiary education. ( On the role and thoughts of M.L. Boonlua concerning Education and university Development, read: ML Boonlua and her ideas on Education by Paitoon Silaratana, former Dean of the Faculty of Education, Chulalongkorn University, first printed in Varasarn Kru Magazine, February- May, BE 2000, reprinted in Boon Bampen; and -

The Inexhaustible Legacy of Wilhelm Von Humboldt

The Inexhaustible Legacy of Wilhelm von Humboldt Chetana Nagavajara German academic circles have their own traditions with which Thai people might not be familiar. Whenever academics meet, they will reach out to each other and ask, “What is your research focus?” (Was ist Ihr Forschungsschwerpunkt?). It, therefore, shows that research is an integral part of the daily life of university teachers. It is interesting to note that they do not ask, "What subject do you teach?" (Was unterrichten Sie?) Teaching is a regular duty, and university professors in the humanities and social sciences normally have 3 teaching assignments, the first, being a large-class lecture; the second, a basic seminar; and the third, an advanced seminar (which also functions as a doctoral seminar). The above system has its inner logic. The large-class lecture sometimes has to cater for so many students that they have to use the "largest" lecture hall, which is known in Latin as the "Auditorium Maximum". For most humanities and social sciences subjects, the aforementioned lectures do not specify the levels of the audience, which means that there are no fixed prerequisites for those who attend. In such cases, the professors need to be highly experienced in transmitting their subjects in a way that is flexible enough for the freshmen to understand; at the same time, the lectures should benefit senior students. Specifically, these lectures should assume the role of a "public lecture" (known in German as “öffentlicher Vortrag”). It can be observed that sometimes the attendees are not regular students, but members of the general public interested in academic and intellectual enrichment, including pensioners who would like to spend their free time studying, or housewives with sufficient educational background, or journalists who write semi-academic columns for newspapers. -

JSS 063 2A Front

.. JOURNAL . OFTHE lAM SOCIETY THE SIAM SOCIETY PATH.ON His Majesty the King VICE-PA'l'HONS Her Majesty the Queen Her l\lajesty Queen Rambai Barni Her Royal Highness the Princess of Songkhla I-ION. VICE-PRESIDENTS H.S.H. Prince Ajavadis Diskul Mr. Alexander B. Griswold COUNCIL OF THE SIAl\1 SOCIE'l'Y I<'OH. 1071>-1!!76 H.R. H. Prince Wan Waithayakorn, Kromamun Naradhip Bongsprabandh President H.E. Mr. Sukich Nimmanhaeminda Senior Vice-President H.S.H. Prince Subhadradis Diskul Vice-President M.R. PatanachGi Jayant Vice-President and Honorary Treasurer M.R. Pimsai Amranand Honorary Secretary Dr. Tej Bunnag Honorary Editor, Journal of the Siam Society Miss Elizabeth Lyons Honorary Librarian Dr. Tern Smitinand Leader, Natural History Section Mr. Kim Atkinson Mrs. Katherine Buri Dr. Dusit Banijbatana Mrs. Chamnongsri Rutnin Dr. Chetana Nagavajara H.E. Mr. F.B. Howitz Mr. Graham Lucas M.L. Manich Jumsai Mr. F.W.C. Martin Mrs. Nisa Sheanakul Dr. Piriya Krairiksh Mrs. Edwin F. Stanton Mr. Perry J. Stieglitz Mr. Dacre Raikes Mr. Sulak Sivaraksa Mrs. Lois A. Seale Mr. Utbai DW)Iakasem ), '~t I . ' ~ :!!:·_·,~ JOURNAL OF THE I SIAM SOCIETY l J JULY 1975 volume 63 part 2 •.. " . .\ ';.··· © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE SIAM SOCIETY JULY 1975 THE jOURNAL OF THE SIAM SOCIETY contents of volume 63 part 2 july 1975 Page Editorial and De1lication i Papers presented at the Workshop on Southeast Asian Languages T~eme: Linguistic Problems in Minority/Majority Group Relation~ in Southeast Asian Countries Mahidol University, Bangkok, 13-17 January 1975 A.G. -

Silpakornuniversity

Silpakorn University Journal of Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts Copyright All rights reserved. Apart from citations for the purposes of research, private study, or criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any other form without prior written permission by the publisher. Published by Silpakorn University Printing House. Silpakorn University, Sanamchandra Palace Campus, Nakhon Pathom 73000 ©Sillpakorn University ISSN 1513-4717 Editorial Advisory Board Silpakorn University Journal of Emeritus Prof. Chetana Nagavajara, Ph.D. Social Sciences, Humanities, and Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, Arts is published in January and June Thailand by Silpakorn University. The journal Prof. Santi Leksukhum, Ph.D. features articles and research notes/ Department of Art History, Faculty of Archaeology, articles in the fields of Art and Silpakorn University, Thailand Design and the Social Sciences and Emeritus Prof. Kusuma Raksamani, Ph.D. Humanities. Its aim is to encourage Department of Oriental Languages, Faculty of Archaeology, and disseminate scholarly Silpakorn University, Thailand contributions by the University’s Assoc. Prof. Rasmi Shoocongdej, Ph.D. faculty members and researchers. Faculty of Archaeology, Silpakorn University, Thailand Well researched, innovative works Assoc. Prof. Maneepin Phromsuthirak, Ph.D. by other scholars are welcome. A Faculty of Arts, Silpakorn University, Thailand review committee consisting of Prof. Samerchai Poolsuwan, Ph.D. academic experts in the relevant fields Faculty of Sociology & Anthropology, will screen all manuscripts, and the Thammasat University, Thailand editorial board reserves the right Assist. Prof. Wilailak Saraithong, Ph.D. to recommend revision/ alteration, English Department, Faculty of Humanities, if necessary, before their final Chiang Mai University, Thailand acceptance for publication. -

Educated at Yale University and the University of Hawaii

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS Kennon Breazeale Born 1944; educated at Yale University and the University of Hawaii; currently completing a Master's degree in history based upon research conducted in Thailand in 1969-70 under the sponsorship of the East-West Center in Hawaii. Jane Bunnag M.A. Cambridge, Ph.D. London; London-Cornell Project for South and Southeast Asia Scholar in Thailand 1966-67; Research Fellow and then Assistant Lecturer in Social Anthropology at the London School of Oriental and African Studies, 1967-69; since 1969 with United Nations agencies in Bangkok. David P. Chandler Born 1933, New York; B.A. Harvard, M.A. Yafe, Ph.D. candidate, University of Michigan; he lived two years in Cambodia as a Foreign Service Officer, and is currently dividing his time between Bangkok, Phnom-Penh and Paris doing research on 18th and 19th century Cambo dian political history. He is one of the co-authors of In Search of Southeast Asia ed. Steinberg (Praeger, New York and London) 1971. Chetana Nagavajara Born 1937, Bangkok; B.A. Cambridge, Ph.D. Ttibingen; formerly with the Educational Planning Office and SEAMES and now Assistant Professor of German, Silapakorn University, Nakorn Pathom. Achille Clarac Born 1903, Nantes; Licence-en-Droit and Diplome d'Etudes Supe rieures in Law, Paris. He entered the French Diplomatic Service in 1930 and served successively in Washington, Teheran, Tetuan, Algiers, Lisbon Chungking, Baghdad, and Munich, with occasional spells in Paris. He was appointed Ambassador to Syria in 1955 and was Ambassador to Thailand from 1959 to 1968 when he retired to divide his time between his Thai house in Prapadeng and his wine-producing estate at Oudon, near Nantes. -

Music-Making Versus the Commodification of Music

MUSIC-MAKING VERSUS Devil in disguise, there is one word in THE COMMODIFICATION Faust’s condition that is of utmost significance, namely the word Augenblick. If OF MUSIC: A CALL TO the Devil can help him to reach that supreme ENLIGHTENED AMATEURS moment, he can have his soul: ∗ If I say to that moment: Chetana Nagavajara Do remain! You are so beautiful! (ll. 1,699–700) Preamble: A foretaste of the supreme moment (Augenblick) Faust never quite reaches that moment (or else he would have lost his soul to the Devil), but almost. Nearing his death, having Abstract seen so much, done so much (of good and bad), the dying Faust experiences a foretaste Music-making, fundamentally a communal of the blissful moment which is the ultimate practice, is the source of aesthetic, goal of his pact with Mephistopheles: emotional, and spiritual experience of a kind comparable to the Faustian To that moment I could say: “moment” (Augenblick). The most ideal Do remain, you are so beautiful. musical culture is one in which no clear The trace of my earthly days dividing line exists between practitioners Cannot dissolve into thin air. and listeners, professionals and amateurs, As foretaste of such great happiness, 1 the remnants of which are still discernible I am now enjoying the supreme moment. in present-day Thai classical music. The (ll. 11,581–586) growing professionalism has been exploited by commercial manipulations And having uttered these words, Faust driven by money and technology, resulting passes away. in a smug, push-button consumerism that treats music as a mere commodity. -

Communications from the International Brecht Society. Vol. 19, No. 1 Winter 1990

Communications from the International Brecht Society. Vol. 19, No. 1 Winter 1990 Winston-Salem, North Carolina: International Brecht Society, Inc., Winter 1990 https://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/M3HLL3GNJRCAF8S http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Copyright International Brecht Society. Used with Permission. The libraries provide public access to a wide range of material, including online exhibits, digitized collections, archival finding aids, our catalog, online articles, and a growing range of materials in many media. When possible, we provide rights information in catalog records, finding aids, and other metadata that accompanies collections or items. However, it is always the user's obligation to evaluate copyright and rights issues in light of their own use. 728 State Street | Madison, Wisconsin 53706 | library.wisc.edu ~— COMMUNI from the International I} CAT! ON S Volume 19 r No. 7 « “ the INEN | | | AN pik NACH GEBORE: fe fs Ach wie, die wie den | Wy, peer eT wollker | nk fice pan & pug sein Wied e! teh Mer ch gedenk| UNSRE ; Ml WAASIAT | eg | INTERNATIONAL BRECHT SOCIETY | COMMUN TCATIONS Volume 19. Winter 1990 _ _Number 1 Editor: Michael Gilbert | Department of German & Russian Wake Forest University P.O. Box 7353 Reynolda Station Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27109 USA Telephone: (919) 759-5362/5359 FAX (WFU): (919) 724-9831 BITNET: mjtg*wfu.edu relay.cs.net All correspondence should be addressed to the Editor. COMMUNICATIONS wel- comes unsolicited manuscripts c. 10-12 double-spaced typed pages in length conforming to the MLA Style Manual. Submissions en 5-1/4" for- matted diskettes are acceptable provided files are converted to ASCII. -

Silpakorn University Journal of Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts

Silpakorn University Journal of Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts Copyright All rights reserved. Apart from citations for the purposes of research, private study, or criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any other form without prior written permission by the publisher. Published by Silpakorn University Printing House. Silpakorn University, Sanamchandra Palace Campus, Nakhon Pathom 73000 ©Sillpakorn University ISSN 1513-4717 Editorial Advisory Board Silpakorn University Journal of Emeritus Prof. Chetana Nagavajara, Ph.D. Social Sciences, Humanities, and Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, Arts is published in June by Thailand Silpakorn University. The journal Prof. Santi Leksukhum, Ph.D. features articles and research notes/ Department of Art History, Faculty of Archaeology, articles in the fields of Art and Silpakorn University, Thailand Design and the Social Sciences and Emeritus Prof. Kusuma Raksamani, Ph.D. Humanities. Its aim is to encourage Department of Oriental Languages, Faculty of Archaeology, and disseminate scholarly Silpakorn University, Thailand contributions by the University’s Assoc. Prof. Rasmi Shoocongdej, Ph.D. faculty members and researchers. Faculty of Archaeology, Silpakorn University, Thailand Well researched, innovative works Assoc. Prof. Maneepin Phromsuthirak, Ph.D. by other scholars are welcome. A Faculty of Arts, Silpakorn University, Thailand review committee consisting of Prof. Samerchai Poolsuwan, Ph.D. academic experts in the relevant fields Faculty of Sociology & Anthropology, will screen all manuscripts, and the Thammasat University, Thailand editorial board reserves the right Assist. Prof. Wilailak Saraithong, Ph.D. to recommend revision/ alteration, English Department, Faculty of Humanities, if necessary, before their final Chiang Mai University, Thailand acceptance for publication. -

Language Learning in Europe and Thailand As a Paradigm of Cultural Transition

LANGUAGE LEARNING IN EUROPE AND THAILAND AS A PARADIGM OF CULTURAL TRANSITION Pornsan Watananguhn 1 Introduction: A Lesson from the Revolution of 24th June 1932 " I am determined to give my simultaneously, both insta·nt democracy absolute power to all of my people and prosperity to Siam. But as we now in the Kingdom of Si;im, but I do know, the Revolution did not lead to any not intend to give this supreme basic structural changes in Thai society. authority to any single person or to any groups of men for his or their The People 's Party 's understanding of own advantage." democracy suggests that their political consciousness had its roots in the These above words, spoken by King Rama westernization of the Siamese educational VII before he abdicated in March 1935, system, which took place in the reign of constitute the Majesty' s response to King Rama V (r.1868-1910). The core of Siam' s transition from absolute to the People 's Party, especially those who cons~itutional monarchy, a very dramatic had been trained in Europe, were convinced political event which was fostered by that so long as Siam remained an absolute groups of civilians and military officers monarchy, the country was unwesternized, of the Siamese Army. All of the military and therefore, undeveloped. To elevate officers and civilians were Western Siam to western standard demanded that trained. Many of the military officers had the old political system be replaced with a received training in Germany and France; new, democratic one. In the opinion of the while all of the civilians had been People 's Party, this charge would make the educated in France or England. -

A Hidden Glimpse at Old Thailand? the "Siam Epi- Sode" in Fontane's Novel U Nwiederbringlich Reinhold Grimm* Abstract

turies following the Banise however I A Hidden Glimpse at Old . ' ' had been unaware of any treatments of Thailand? The "Siam Epi Thai topics in German letters; and the sode" in Fontane's Novel quite recent, though very important and U nwiederbringlich meritorious, exception to the rule, Rella Kothmann's collection ofvarious Thai texts in German rendition, her Das Reinhold Grimm* . siamesische Liicheln ("The Siamese Smile"),3 appeared only after I had Abstract penned and delivered my lecture-in fact, simultaneously, as it were, with my aforesaid book. Hardly ever do images of Thai or Thai land occur in German literature. Alas, such a paucity of evidence is by Granted, there exists an early if seem ingly isolated forerunner from the 17th no means restricted to the realm ofbelles lettres, nor ofliterary endeavors at large, century: namely, Heinrich Anshelm von either. The pertinent handbooks bear Zigler und Kliphausen's voluminous embarrassing witness to this. Neither in Baroque novel in titled Die asiatische Banise ("The Asian Banise" [which is Frenzels's Stoffe der Weltliteratur or Schmitt's Stoff-und Motivge-schichte the name of the heroine]).' I adduced it, der deutschen Literatur, nor in the and briefly discussed its opening scene, in my talk "What is a Good Dramatic Daemmrichs' jointly authored Themes Text? A German's Answer to a Thai's and Motifs in Western Literature and Wiederholte Spiegelungen: Themen und Question" that I gave in Bangkok almost Motive in der Literatur, 4 can the slight a decade ago, and which was subse est, the most fleeting mention of Thai quently published, in a Thai translation by Chetana Nagavajara, in Silpakorn land (or of Siam, for that matter) be University's Journal of the Faculty of 3 Das siamesische Liicheln: Literatur und Arts and, in its English original, in my Revolution in Thailand. -

WRAP THESIS Tungtang 2011.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36865 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Shakespeare in Thailand by Paradee Tungtang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre Studies and Translation Studies School of Theatre, Performance and Cultural Policy Studies, University of Warwick March 2011 i Table of Contents Page Table of Contents i List of Illustrations v Acknowledgements xi Declaration xiii Abstract xiv Preface xvi Introduction 1 Part One: Translating Shakespeare in Thailand Chapter I Shakespeare’s Introduction to Thailand: An Overview 39 King Vajiravudh and His Literary and Dramatic Activities 45 Chapter II An Analysis of King Vajiravudh’s Translations and 57 Adaptations of Shakespeare Basic Thai Verse Types 59 Case Study: Phraya Ratchawangsan, King Vajiravudh’s 70 Adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello Phraya Ratchawangsan’s characters and plot summary 76 Staging Phraya Ratchawangsan in the Siamese dance drama style 79 Phraya Ratchawangsan following the convention of Siamese 84 dance drama Introductory word use 86 Types of Bot (passages of narration) in Siamese dance 89 drama scripts Analysis -

PROGRAM for GRAND OPENING CEREMONY of STT42 30Th November 2016

PROGRAM FOR GRAND OPENING CEREMONY OF STT42 30th November 2016 VIBHAVADEE BALLROOM, CENTARA GRAND AT CENTRAL PLAZA LADPRAO, BANGKOK Time Events 8:00-8:30 All guests are seated in Vibhavadee Ballroom 9:00 - Arrival of Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn - Presentation of Souvenirs and Program Book from Associate Professor Dr.Napavarn Noparatnaraporn, President of The Science Society of Thailand under the Patronage of His Majesty the King, Associate Professor Dr.Viroch Impithuksa, Chairperson of Kasetsart University Council and Associate Professor Dr.Pranut Potiyaraj, Chairperson of Academic Affairs of STT42 - Report on STT42 by Professor Dr.Piamsook Pongsawasdi, Chairperson of STT42 - Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn graciously presents plaques to Distinguished Keynote Lecturer, 2016 Senior Scientists, 2016 Thailand Outstanding Scientist, 2016 Outstanding Technologists, 2016 Young Scientists, 2016 Young Technologist, 2016 Outstanding Science Teachers, Winners of 2015 National Science Projects Competition, and STT42 Premium Sponsors - Grand Opening Address by Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn 9:40 - Brief introduction of Distinguished Keynote Lecturer Professor Dan Shechtman, 2011 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry by Dean of Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University: Professor Dr.Supa Hannongbua - Keynote Lecture: “Quasi -Periodic Crystals -A Paradigm Shift in Crystallography” Professor Dan Shechtman 10:20 - Brief introduction of Professor Vorasuk Shotelersuk, M.D., 2016 Thailand Outstanding Scientist