A Comparison of Patients Relapsing to Addictive Drug Use with Non

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos Santana on New 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection Featuring Five Limited-Edition Signature and Replica Guitars Exclusive Guitar Collection Developed in Partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender®, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars to Benefit Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre Antigua Limited Quantities of the Crossroads Guitar Collection On-Sale in North America Exclusively at Guitar Center Starting August 20 Westlake Village, CA (August 21, 2019) – Guitar Center, the world’s largest musical instrument retailer, in partnership with Eric Clapton, proudly announces the launch of the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection. This collection includes five limited-edition meticulously crafted recreations and signature guitars – three from Eric Clapton’s legendary career and one apiece from fellow guitarists John Mayer and Carlos Santana. These guitars will be sold in North America exclusively at Guitar Center locations and online via GuitarCenter.com beginning August 20. The collection launch coincides with the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Festival in Dallas, TX, taking place Friday, September 20, and Saturday, September 21. Guitar Center is a key sponsor of the event and will have a strong presence on-site, including a Guitar Center Village where the limited-edition guitars will be displayed. All guitars in the one-of-a-kind collection were developed by Guitar Center in partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars, drawing inspiration from the guitars used by Clapton, Mayer and Santana at pivotal points throughout their iconic careers. The collection includes the following models: Fender Custom Shop Eric Clapton Blind Faith Telecaster built by Master Builder Todd Krause; Gibson Custom Eric Clapton 1964 Firebird 1; Martin 000-42EC Crossroads Ziricote; Martin 00-42SC John Mayer Crossroads; and PRS Private Stock Carlos Santana Crossroads. -

For Immediate Release March 5, 2004

For Immediate Release March 5, 2004 Contact: Bendetta Roux, New York 212.636.2680 [email protected] Jill Potterton , London 207.752.3121 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S NEW YORK TO OFFER GUITARS FROM ERIC CLAPTON SOLD TO BENEFIT THE CROSSROADS CENTRE IN ANTIGUA “These guitars are the A-Team … What I am keeping back is just what I need to work with. I am selling the cream of my collection.” Eric Clapton, February 2004 Crossroads Guitar Auction Eric Clapton and Friends for the Crossroads Centre June 24, 2004 New York – On June 24, 1999, Christie’s New York organized A Selection of Eric Clapton’s Guitars ~ In Aid of the Crossroads Centre, a sale that became legendary overnight. Exactly five years later, on June 24, 2004, Christie’s will present the sequel when a group of 56 guitars, described by Eric Clapton as “the cream of my collection,” as well as instruments donated by musician friends such as Pete Townshend, will be offered. Featuring iconic instruments such as ‘Blackie’ and the cherry-red 1964 Gibson ES-335, Crossroads Guitar Auction ~ Eric Clapton and Friends for the Crossroads Centre, promises to be a worthy successor to the seminal 1999 sale. The proceeds of the sale will benefit the Crossroads Centre in Antigua. Referring to the selection of guitars that will be offered in this sale, Eric Clapton said: “These guitars are in fact the ones that I kept back from the first auction because I seriously couldn’t consider parting with them at that point … I think they are a really good representation of Rock Culture .. -

Eric Clapton Eric Clapton

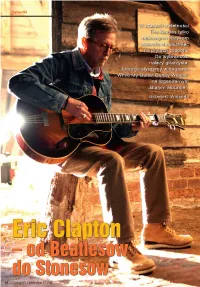

Sylwetki W czasach świetności The Beatles tylko nielicznym muzykom udawało się zaistnieć na płytach zespołu. Do wybrańców należy gitarzysta, którego słyszymy w nagraniu „While My Guitar Gently Weeps” na legendarnym „Białym albumie”. Grzegorz Walenda Eric Clapton – od Beatlesów do Stonesów 94 Hi•Fi i Muzyka 11/16 Sylwetki itarzystą tym był Eric Clapton, Początki Nie mniej utalentowani od Claptona byli a fakt, że wystąpił z Beatlesa- Pierwsza kapela, z którą się związał, pozostali członkowie Cream. Zwłaszcza mi, świadczy o jego wyjątko- będąc jeszcze nastolatkiem, nazywała się Ginger Baker cieszył się uznaniem wśród wym talencie. Artysta wydał właśnie 23. The Roosters i grała rhythm and bluesa. fachowców. Śmiało konkurował z inną solową płytę (nie licząc filmowej „Rush”) Dziś chyba tylko najwięksi fani Claptona ówczesną gwiazdą perkusji – Keithem i znów się o nim mówi. Clapton to legenda, o niej pamiętają. Dopiero gdy dołączył do Moonem z The Who. Gra Bakera miała a jego premierowy krążek trafił do setki formacji Yardbirds, grającej rock and rolla w sobie więcej elementów jazzowych najlepiej sprzedających się albumów „Bill- z elementami bluesa, jego kariera nabra- i bluesowych niż popisy kolegi po fachu. b o a r d u ”. ła tempa. Przypomnę, że przez Yardbirds Moon specjalizował się przede wszystkim przewinęło się kilka rockowych i blueso- w dynamicznym rocku. Na fali mimo problemów wych sław, m.in. Jeff Beck i Jimmy Page. Bilety na koncerty Cream rozchodzi- Ostatnio o muzyku jest głośno również Z Yardbirds Clapton nagrał swój pierwszy ły się jak ciepłe bułeczki, a płyty znikały z innego powodu. Media (w tym wspo- znaczący przebój – kompozycję Grahama ze sklepowych półek. -

“…Standing by the Crossroads…” Seven Signature Tones from Eric Clapton

“…standing by the crossroads…” Seven signature tones from Eric Clapton. C R O S S R O A D S ™ • L I M I T E D E D I T I O N Crossroads™ A “Sunshine of Your Lo e” R From v to T A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this pedal is being “Layla Unplugged”…seven signature I donated to Crossroads Centre, an International Centre S of Excellence for the treatment of alcohol, drugs and tones from Eric Clapton in a limited- T other addictive disorders. ® edition DigiTech effects pedal. S E R “Badge” “Layla” n conjunction with Eric Clapton, I Goodbye Layla and Other we have helped recreate some of his E I Assorted Love Songs S “Crossroads” classic tones in a DigiTech pedal by Wheels of “Lay Down Sally” applying our new Production Modeling™ E Fire, Li e at Slowhand v ™ F the Fillmore “Layla” technology to create Crossroads. F “Sunshine of Unplugged, LIVE For the fi rst time, complex studio E Your Love” C and live effects can be accurately Disraeli Gears “Reptile” T Reptile reproduced thanks to Production S Modeling via our AudioDNA® DSP P super-chip. If you’re a Slowhand fan E D or just want to add some unique tones Crossroads™ 7 New DigiTech Production Modeling™ A technology accurately recreates seven signature Eric Clapton tones. to your effects palette, demo the L 7 Legendary “woman tone” 7 Raw “Crossroads” blues captured live limited edition Crossroads pedal 7 Embracing stereo spectrum of a swirling Leslie™ 7 Intimacy of Unplugged 7 Enduring warmth of “Reptile” 7 Custom artist at your DigiTech dealer today. -

Número 33 – Febrero 2014 * CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA

1 Número 33 – Febrero 2014 * CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Índice Directorio PORTADA Blues Shock: Billy Branch & The Son Of Blues. Imagen cortesía de Blind Pig Records. Agradecimientos para el diseñador del arte: Eduardo Barrera Arambarri y al autor de la foto: Cultura Blues. La revista electrónica Tony Manguillo (1) ..………………………………………………………………….…………….. 1 “Un concepto distinto del blues y algo más…” www.culturablues.com ÍNDICE - DIRECTORIO ……..…………………………………………..….… 2 Esta revista es producida gracias al Programa EDITORIAL To blues or not to blues (2) ..…..………………….………… 3 “Edmundo Valadés” de Apoyo a la Edición de HUELLA AZUL Billy Branch. Entrevista exclusiva (3 y 4) .….….…. 4 Revistas Independientes 2013 del Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes DE COLECCIÓN Un disco, un video y un libro (5) ………………...... 7 EL ESCAPE DEL CONVICTO 20 grandes slides del blues eléctrico. Primera Parte (6) ................. 11 Año 4 Núm. 33 – febrero de 2014 Derechos Reservados 04 – 2013 – 042911362800 – 203 BLUES A LA CARTA Registro ante INDAUTOR Clapton está de vuelta, retrospectiva en doce capítulos. Capítulo once (5) ……………………………………………….………………………... 16 Director general y editor: José Luis García Fernández PERSONAJES DEL BLUES XI Nominados a los premios de la Blues Foundation (5) ………….......…..21 Subdirector general: José Alfredo Reyes Palacios LÍNEA A-DORADA Llegará la Paz (7) ....................................... 26 Diseñador: José Luis García Vázquez COLABORACIÓN ESPECIAL I Tres festivales de Blues en el centro del país Pt. III (8)…………...…..….29 Consejo Editorial: CULTURA BLUES EN… Luis Eduardo Alcántara Cruz Hospital de Pediatría. CMN Siglo XXI. Un camino acústico por Mario Martínez Valdez el blues. - Multiforo Cultural Alicia. Presentación del libro de María Luisa Méndez Flores Juan Pablo Proal: “Voy a morir. -

April 2013 News Releases

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 4-1-2013 April 2013 news releases University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "April 2013 news releases" (2013). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 22155. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/22155 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - UM News - The University Of Montana my.umt.edu A to Z Index Directory UM Home April 2013 News 04/30/2013 - Missoula College Presents Seminar by 'Design+Build' Project Designer - Bradley Layton 04/30/2013 - UM Unveils New Brand Initiatives - Peggy Kuhr 04/30/2013 - UM To Host Free Sexual Assault Awareness Seminars - Casey Gunter 04/30/2013 - Missoula College Offers Course In Children's Communication - Kim Reiser 04/30/2013 - MC Culinary Students Prepare American Barbecue for Annual Capstone Dinner - Tom Campbell 04/29/2013 - Summer Field Courses Offered In Montana, Alaska, Canadian Rockies - -

Drug and Alcohol Treatment in Antigua and Barbuda

Drug and Alcohol Treatment in Antigua and Barbuda Presented by: Crossroads Treatment Center – Kim Martin ONDCP- Marcia Edwards Drug and Alcohol Treatment in Antigua and Barbuda The ONDCP is the National Coordinating Entity for OAS/CICAD The Organization undertook the responsibility to re-energize the National Drug Council and was instrumental in the drafting and passage of the National Anti- Drug Strategy. The Drug Plan • Strengthen and increase the effectiveness of institutions that provide treatment and rehabilitation programmes to ensure that all persons who need treatment and rehabilitation have equal access to such services. • Support and strengthen treatment and rehabilitation programmes for persons suffering from substance abuse to include their psychological, social and biological needs. The Drug Plan Cont’d Introduce procedures to monitor treatment provided to drug abusers in an effort to ensure desired standards. Train persons at all levels of relevant disciplines of treatment and rehabilitation services. Strengthen research capabilities to ensure timely collection, analysis and dissemination of information. Crossroads Centre Antigua Crossroads Centre was founded in 1997 by Mr. Eric Clapton on the island of Antigua • Capacity: 8 detoxification beds; 28 residential beds • Serves: Men and women 18 years of age and older • Treats: Primary substance use disorders; most clients also have co-occurring and co- morbid disorders Crossroads Centre Programs Residential Treatment: 4 – 6 weeks Transitional Living: Antigua and Delray -

Eric Clapton

Eric Clapton http://www.gibson.com/Products/Electric-Guitars/Les-Paul/Gibson- Custom/Eric-Clapton-1960-Les-Paul.aspx Group 2 Lauren Hartmann, Sarah Youssef, Benjamin Markham, and Suyog Dahal Overview ❖ Artist Biography ❖ Musical Influences ❖ Musical Style ❖ Other Music at the Time ❖ Musical Analysis ❖ Clapton’s Influence ❖ Legacy http://www.ericclapton.com/eric-clapton-biography?page=0%2C2 ❖ Conclusion ❖ References Why We Chose Eric Clapton ❖ We chose Eric Clapton because he is considered one of the most important and influential guitarist of times. ❖ We were interested to learn about how his personal life and choices influenced his musical style. http://thubakabra.deviantart.com/art/Eric- Clapton-333962401 Eric Clapton’s Early Life ❖ Born Eric Patrick Clapton on March 30, 1945 ❖ The son of an unmarried couple, Patricia Molly Clapton and and Edward Walter Fryer. ❖ Edward Walter Fryer was a Canadian soldier stationed in England during WWII. Before Eric was born he returned to his wife back in Canada. ❖ It was difficult on Patricia to raise Eric on her own. Her parents, Rose and Jack Clapp were the primary caregiver of Eric, and raised him http://www.seymourduncan.com/forum/ as their own. showthread.php?127804-quot-So-and-so-played- THIS-guitar-quot (Eric Clapton and WBR, n.d.). Eric Clapton’s Early Life ❖ He was brought up in a musical household ➢ His grandmother played the piano ➢ His mother and uncle always had big bands playing throughout the house ❖ At the age of 9 he found out the truth about his parents ➢ Was affected tremendously by this truth and began to be moody and distant. -

2019 BT FINAL-Low

BURLINGTON ONTARIO, CANADA OFFICIAL VISITOR GUIDE 2019 - 2020 ADVENTURE AWAITS CULINARY EXPERIENCES WHAT’S NEW IN #BURLON tourismburlington.com | 1.877.499.9989 !"$ It’s a matter of view. Discover the exciting new look of Burlington’s ONLY downtown hotel, steps from unique shops, dining, spas, museums, theatres and festivals. Contemporary guestrooms and public space offer a dramatic waterfront setting and views. b&b onsite restaurant and patio feature seasonal menus overlooking Spencer Smith Park and Lake Ontario. 5,000 square feet of fl exible function space is ideal for groups up to 220 people. FREE HOT BREAKFAST LAKESIDE INDOOR POOL PET FRIENDLY BUFFET AND WI-FI AND FITNESS FACILITY 2020 LAKESHORE RD. BURLINGTON, ON L7R 4G8 waterfronthotelburlington.com 905-681-5400 WHAT’S INSIDE? Welcome to Burlington 4 It’s a matter of view. See & Do 8 Arts & Culture 16 Events 24 Maps 37 Shop 41 Health, Recreation & Sport 47 Dine 50 Sweet Treats 59 Meet 60 Services & Associations 63 Stay 66 VISITOR INFORMATION CENTRE 414 Locust Street, Burlington, Ontario, L7S 1T7 Cycle friendly location. Open Year Round (including weekends) Burlington souvenirs, maps Mid June- End of August: Daily 8 a.m. – 6 p.m. and postcards are sold at Discover the exciting new look of Burlington’s ONLY downtown hotel, September-Mid June: Daily 9 a.m. – 4 p.m. the Centre. Free Wifi. steps from unique shops, dining, spas, museums, theatres and festivals. Contemporary guestrooms and public space offer a dramatic waterfront setting and views. Phone: ...................................................................... 905.634.5594 b&b onsite restaurant and patio feature seasonal menus overlooking Toll Free: ..................................................................1.877.499.9989 Spencer Smith Park and Lake Ontario. -

LSA Template

CONCERTS Copyright Lighting &Sound America September 2010 http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.html uitar Heroes A top team gets together G to support Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre By: Sharon Stancavage t’s the best show on the more, it’s hard to argue his point. Clapton’s tours), with technical planet,” says associate The event is the Crossroads Guitar direction by Upstaging’s John production designer and Festival, which took place at Huddleston. The event was created “I programmer Eric Wade. With a Chicago’s Toyota Park in late June. by Eric Clapton to support his lineup that includes Eric The event, which was produced by Crossroads Centre for the treatment Clapton, Steve Winwood, Jeff Upstaging Inc., of Sycamore, Illinois, of addictions in Antigua. The event’s Beck, John Mayer, B.B. King, ZZ Top, featured production design by Dave main stage featured more than two the Allman Brothers, Buddy Guy, and Maxwell (also known for his work on dozen performers; the Guitar Center n i k t a N l u a P / g n i g a t s p U : s o t o h p l l A Above and right: The main stage by day. For this year’s event, Dave Maxwell was responsible for the graphics as well as the production design. 76 • September 2010 • Lighting &Sound America www.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2010 • 77 CONCERTS especially live festivals, manage to used them,” notes Wade. “It’s a very “Compared to the Clapton tours that consoles, they adjusted the front-of- achieve: Everything went ahead of cool light, which we used for stage I’ve been doing both in the US this house and monitor footprints accord - schedule on every level that day,” and audience washes. -

Eric Clapton - Sein Leben Und Seine Musik Bis Heute Von Thomas Mießeler, Clapton.De

Eric Clapton - sein Leben und seine Musik bis heute Von Thomas Mießeler, Clapton.de Geburt, Eltern, Großeltern Eric Patrick Clapton wurde am 30. März 1945 im Hause seiner Großeltern in Surrey, England, geboren. Er war der uneheliche Sohn der erst 16-jährigen Patricia Clapton. Sein Vater, Edward Fryer, ein 24-jähriger kanadischer Soldat, war zu dieser Zeit in England stationiert und zog noch vor Claptons Geburt zurück zu seiner Frau nach Kanada. Für ein unverheiratetes, 16-jähriges Mädchen war es in den 40er Jahren äußerst schwierig, ein Kind eigenständig großzuziehen. Daher übernahmen Patricias Mutter Rose Clapp und ihr Stiefvater Jack Clapp die Vormundschaft über den jungen Eric. Patricias Nachname, Clapton, stammte von ihrem leiblichen Vater, Reginald Clapton, der 1933 gestorben war. Patricia lernte derweil in Deutschland einen anderen kanadischen Soldaten kennen, Frank McDonald. Nach ihrer gemeinsamen Hochzeit zogen sie nach Kanada aufgrund Franks militärischer Karriere. Patricia bekam noch drei weitere Kinder. Claptons Kindheit und Jugend Eric, der in der Obhut seiner Großeltern aufwuchs, sollte von den Umständen seiner Geburt lange Zeit nichts wissen. Er verhielt sich in seiner Kindheit still und zurückhaltend. In der Schule galt er allerdings als ein überdurchschnittlicher Schüler mit einer ausgeprägten Begabung im künstlerischen Bereich. Als einschneidendes Erlebnis bezeichnet Clapton bis heute sein neuntes Lebensjahr, dem Jahr, in dem er die wahren Hintergründe über seine leiblichen Eltern erfahren sollte. Es passierte, als seine Mutter Patricia zu Besuch nach England kam. Eric war bis dato fest davon überzeugt, dass seine Großeltern seine Eltern und seine Mutter seine große Schwester gewesen war. Die Konfrontation mit der Wahrheit war für den jungen Eric ein tiefer Schock. -

AMD Returns to the Crossroads with Eric Clapton

July 27, 2007 AMD Returns to the Crossroads With Eric Clapton -- Rhino Entertainment Brings AMD Opteron(TM) Processors Back to Record Eric Clapton's Crossroads Guitar Festival 2007; Expect to Mix and Master on 'Barcelona' Workstations -- CHICAGO--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- AMD (NYSE:AMD) announced today that it will again chronicle Eric Clapton's Crossroads Guitar Festival this year as it did in 2004, this time using multi-core AMD Opteron(TM) processor-based digital audio workstations (DAWs) and adding notebook PCs into the mix for smaller stages. The Crossroads Guitar Festival 2007 will be recorded on July 28, 2007 at Toyota Park in Chicago and will feature live performances by legendary guitar players including Eric Clapton, B.B. King, Jeff Beck, Willie Nelson, Vince Gill, Buddy Guy, Robert Randolph, Doyle Bramhall II, John Mayer, Jimmie Vaughan, Johnny Winter, Robert Cray, Sheryl Crow and many more artists. AMD Opteron processor-based DAWs were used by Clapton's team on his latest world tour to capture every live show in HD audio format. The mission-critical demands put on a computer by the particularly heavy load of recording live performances require flawless system performance. The AMD Direct Connect Architecture with HyperTransport helps insure that no system bottlenecks cause loss of performance data. Rhino Entertainment expects to mix and master a live concert 5.1 surround sound DVD of the Festival using systems based on the upcoming quad-core AMD Opteron processor codenamed "Barcelona." "As a live sound engineer, I cannot afford to worry about recording while I'm mixing live audio," said Robert Collins, live sound engineer for Eric Clapton's 2007 World Tour.