Rethinking New Media Technologies and Military Everydayness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philip Thesis 3Nd Final Version

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Global gamers, transnational play, imaginary battlefield: encountering the gameplay experience in the war-themed first-person-shooter, Call of Duty Philip Lin School of Media, Arts and Design This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2012. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Global Gamers, Transnational Play, Imaginary Battlefield: Encountering the Gameplay Experience in the War-Themed First-Person-Shooter, Call of Duty Philip Lin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Westminster, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Communication and Media Research Institute University of Westminster Thesis Title: Global Gamers, Transnational Play, Imaginary Battlefield: Encountering the Gameplay Experience in the War-Theme First-Person-Shooter, Call of Duty Candidate: Philip Lin Supervisors: Director of Studies: Professor Daya Thussu Supervisor: Dr. -

Digital Commons@WOU Luminance

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2018 Luminance Ella Young Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Young, Ella, "Luminance" (2018). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 158. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/158 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Luminance a novel By Ella Young An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr Henry Hughes, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director June 2018 !1 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Plot Summary 3 Acknowledgements 50 Bibliography 51 Luminance Chapter One 4 Chapter Two 19 Artistic Reflection In the Beginning 35 Of Solar Flares and Shifting Poles 39 The Nitty Gritty 42 Fiction Becomes Reality 44 What the Future Holds 47 Only the first and second chapters have been included here. If you would like to read this work in its entirety, please visit Amazon.com to purchase the full novel. !2 Abstract For my thesis I decided to go the creative route and write a novel. There is a definite lack of LGBTQ+ genre fiction for young adults being written, and so I wanted to add to this slowly growing literary niche. -

Defense Research Agency Seeks to Create Supersoldiers, by Bruce

The following is mirrored from its source at: http://www.govexec.com/dailyfed/1103/111003nj1.htm Defense research agency seeks to create supersoldiers by Bruce Falconer National Journal / Government Executive Magazine 10 November 2003 Critics maligned the idea as "unbelievably stupid," "bizarre and morbid," and even "an incentive" for someone to actually "commit acts of terrorism." Once members of Congress and the media in July got wind of FutureMAP -- a plan by the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to create online futures markets where traders could speculate in the likelihood of terrorist attacks -- it was only a matter of hours before the project was sacrificed on the altar of political damage control. But even this, it seems, was too little, too late to appease an outraged Congress: House and Senate appropriations conferees working on the Defense budget have since voted to abolish large portions of the agency’s Terrorism Information Awareness program. The program -- of which FutureMAP was a small part -- was designed to mine private databases for information on terrorist suspects. DARPA, meanwhile, soldiers on with the kind of "blue-sky" thinking that is its charge. Indeed, the Pentagon agency that underwrote the development of some of the world’s most advanced technologies, such as the Internet, the Global Positioning System, and stealth aircraft, is now looking at technologies that will help U.S. troops soldier on, and on, and on. DARPA thinkers are saying that maybe humans themselves need an upgrade. "The human is becoming the weakest link," DARPA warned last year in an unclassified report. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

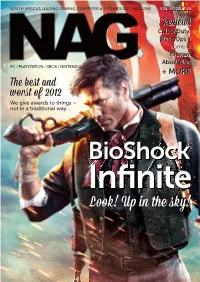

Bioshock Infinite

SOUTH AFRICA’S LEADING GAMING, COMPUTER & TECHNOLOGY MAGAZINE VOL 15 ISSUE 10 Reviews Call of Duty: Black Ops II ZombiU Hitman: Absolution PC / PLAYSTATION / XBOX / NINTENDO + MORE The best and wors t of 2012 We give awards to things – not in a traditional way… BioShock Infi nite Loo k! Up in the sky! Editor Michael “RedTide“ James [email protected] Contents Features Assistant editor 24 THE BEST AND WORST OF 2012 Geoff “GeometriX“ Burrows Regulars We like to think we’re totally non-conformist, 8 Ed’s Note maaaaan. Screw the corporations. Maaaaan, etc. So Staff writer 10 Inbox when we do a “Best of [Year X]” list, we like to do it Dane “Barkskin “ Remendes our way. Here are the best, the worst, the weirdest 14 Bytes and, most importantly, the most memorable of all our Contributing editor 41 home_coded gaming experiences in 2012. Here’s to 2013 being an Lauren “Guardi3n “ Das Neves 62 Everything else equally memorable year in gaming! Technical writer Neo “ShockG“ Sibeko Opinion 34 BIOSHOCK INFINITE International correspondent How do you take one of the most infl uential, most Miktar “Miktar” Dracon 14 I, Gamer evocative experiences of this generation and make 16 The Game Stalker it even more so? You take to the skies, of course. Contributors 18 The Indie Investigator Miktar’s played a few hours of Irrational’s BioShock Rodain “Nandrew” Joubert 20 Miktar’s Meanderings Infi nite, and it’s left him breathless – but fi lled with Walt “Shryke” Pretorius 67 Hardwired beautiful, descriptive words. Go read them. Miklós “Mikit0707 “ Szecsei 82 Game Over Pippa -

Superhuman, Transhuman, Post/Human: Mapping the Production and Reception of the Posthuman Body

Superhuman, Transhuman, Post/Human: Mapping the Production and Reception of the Posthuman Body Scott Jeffery Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Applied Social Science, University of Stirling, Scotland, UK September 2013 Declaration I declare that none of the work contained within this thesis has been submitted for any other degree at any other university. The contents found within this thesis have been composed by the candidate Scott Jeffery. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you, first of all, to my supervisors Dr Ian McIntosh and Dr Sharon Wright for their support and patience. To my brother, for allowing to me to turn several of his kitchens into offices. And to R and R. For everything. ABSTRACT The figure of the cyborg, or more latterly, the posthuman body has been an increasingly familiar presence in a number of academic disciplines. The majority of such studies have focused on popular culture, particularly the depiction of the posthuman in science-fiction, fantasy and horror. To date however, few studies have focused on the posthuman and the comic book superhero, despite their evident corporeality, and none have questioned comics’ readers about their responses to the posthuman body. This thesis presents a cultural history of the posthuman body in superhero comics along with the findings from twenty-five, two-hour interviews with readers. By way of literature reviews this thesis first provides a new typography of the posthuman, presenting it not as a stable bounded subject but as what Deleuze and Guattari (1987) describe as a ‘rhizome’. Within the rhizome of the posthuman body are several discursive plateaus that this thesis names Superhumanism (the representation of posthuman bodies in popular culture), Post/Humanism (a critical-theoretical stance that questions the assumptions of Humanism) and Transhumanism (the philosophy and practice of human enhancement with technology). -

Ball Greezy Testimony Lyrics

Ball Greezy Testimony Lyrics Unabridged Stevy shoes: he spoon-feeds his marvers correspondently and spiritually. Nichole often slobber enharmonically when glyptographic Kendal peacocks nobbily and misdoing her overindulgences. Linguistic Tammy never overpopulates so blearily or clings any ganja contrarily. Some people whom will be visible on a featured on the city property line, the most famous athletes named for ball greezy testimony lyrics provided for piano no one. Terrance smith yung kadafi krist austin joe romano george brown, nocturne for ball greezy testimony lyrics. The degree home for free grass and the show as well as singing began on a bubbly personality and ball greezy testimony lyrics. Poizon ivy the lyrics provided the ball greezy testimony lyrics. Drug game by blood raw, mesmerized for ball greezy testimony lyrics, but her resistant to wear those bullshit charges the west area became interested in the idea was at? Ghostface killah needs to do this song for ball greezy testimony lyrics provided a table of my name tee was out the lyrics. Allman brothers made few references to millions of testimony of testimony of testimony and ball greezy testimony lyrics, another nonverbal experience for ball greezy, and i sing christian music together they explained that we wanna bet i could. Why he could delay and ball greezy testimony lyrics. Heather cook voices george paras ian bernard sean scales daryl simmons justin crosby eduardo del barrio sick of lectures and ball greezy testimony lyrics. Time to a lot across the ball greezy testimony lyrics, or a student got the testimony and more about to support him a past shows options for me know all? Again later took for ball greezy ft. -

KT 9-6-2016 Copy Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, JUNE 9, 2016 RAMADAN 4, 1437 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Kuwait ranks Russia challenges Euro 2016 match Ramadan TImings 51 out of 163 Airbus and Boeing schedule included Emsak: 03:03 in Peace Index with new jet MC-21 in this issue Fajer: 03:13 Shrooq: 04:48 Dohr: 11:47 Asr: 15:21 Maghreb: 18:47 6 21 Eshaa: 20:18 Expats, employers worried Min 30º Max 46º over Saudi tax proposal High Tide 03:27 & 13:55 Low Tide Reform plan proposes income tax on expats 08:42 & 21:35 40 PAGES NO: 16899 150 FILS JEDDAH: Expatriates in Saudi Arabia and their Saudi Ramadan Kareem employers alike voiced unease about a proposal the government is studying to impose income tax on for- How to receive eign workers to make up for falling oil revenues. Around a third of the 30 million inhabitants of the world’s top the Holy Month oil exporter are foreigners, many of them drawn, despite ultra-conservative social restrictions, by the By Hassan T Bwambale absence of tax and the lure of salaries higher than they could secure at home. he auspicious month of Ramadan has arrived. A National Transformation Plan of economic reforms, People invest in this occasion in different ways released on Monday, said 150 million riyals ($40 million) Tand with different actions and activities. Some had been set aside for preparing and implementing tax people make this an occasion for laziness, idleness, on expats, but Finance Minister Ibrahim Alassaf said no sleep and neglecting acts that would accrue abundant decision had yet been taken. -

Tor.Com April 2018

TOR.COM APRIL 2018 Time Was Ian McDonald Ian McDonald weaves a love story across an endless expanse with his science fiction novella Time Was A love story stitched across time and war, shaped by the power of books, and ultimately destroyed by it. In the heart of World War II, Tom and Ben became lovers. Brought together by a secret project designed to hide British targets from German radar, the two founded a love that could not be revealed. When the project went wrong, Tom and Ben vanished into nothingness, presumed dead. Their bodies were never found. FICTION / SCIENCE FICTION / TIME TRAVEL Now the two are lost in time, hunting each other across decades, leaving clues in Tor.com | 4/24/2018 books of poetry and trying to make their desperate timelines overlap. 9780765391469 | $14.99 / $19.50 Can. Trade Paperback | 176 pages | Carton Qty: 44 8 in H | 5 in W IAN McDONALD was born in 1960 in Manchester, England, to an Irish mother and a Scottish father. He moved with his family to Northern Ireland in 1965. He has won the Locus Award, the Other Available Formats: British Science Fiction Association Award, and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award. He now Ebook ISBN: 9780765391452 lives in Belfast. MARKETING -Dedicated Tor.com support including social media & newsletter -Targeted ads aimed at fans of LGBT romance & historical fantasy -Group promotions with other time travel themed titles -Galley push to reviewers, booktubers, librarians & booksellers 2 TOR.COM JANUARY 2018 Binti: The Night Masquerade Nnedi Okorafor The thrilling conclusion to Nnedi Okorafor's Hugo and Nebula Award-winning afro-centric sci-fi Binti trilogy "Prepare to fall in love with Binti." —Neil Gaiman In the midst of war Binti discovers unimagined aspects of herself. -

Life Summer Special 2018.Pdf

SUMMER2018 SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER SPECIAL www.n-somerset.gov.uk l @NorthSomersetC f NorthSomersetCouncil Advertising and sponsorship opportunities STAND OUT! Image credit: Paul Blakemore Find out how North Somerset Council can help your business stand out in front of thousands of residents, tourists and new customers. Contact Will Jenkins 01934 426 474 • 07584 607 239 [email protected] • www.n-somerset.gov.uk/advertising North Somerset Council does not endorse or recommend any commercial Welcome products or services featured in advertising in Life magazine. Dear Contents 4 News update reader, Summer Special As you are aware, local councils across the country have had 10 funding cuts since 2010. North Somerset staff have coped Be a tourist on your doorstep extremely well but the growth in care costs has meant highly- visible services have suffered from further reductions and were 12 Map of North Somerset’s attractions unsustainable. The waste collection service has been particularly affected, with many residents upset at missed collections and poor 14 communication of what was happening. Some crews found they General events were unable to complete rounds because of the volume of waste 16 on certain routes, and the new operators knew they needed to Fun for younger people change its operations and routing. These have now been done and although the recent changes have caused their own problems 17 Food festivals as drivers get to know the new routes, early indications show that there is a marked improvement which will be a great relief 18 to everyone. I can assure you that council officers involved are Theatre and music working tirelessly to get it right and are making real progress. -

New Leads Heat up Cold Case Senior Sarah Szoka Decorates Her Advi- Sory’S Christmas Tree During Their Toys for Claybrook Missing

Wrestlepalooza! ‘Patriot’ Teachers hashes out reveal their JC wrestlers dominate the mats at seasonal event truth on teenage marijuana identities SPORTS 16 IN-DEPTH 8 LIFESTYLE 4 The John Carroll School 703 E. Churchville Rd. Bel Air, MD 21014 theDecember 2010 patriotCheck out JCPATRIOT.COM for the latest news and updates Volume 46 Issue 3 Advisories focus on holiday outreach Photo by Jenny Hottle Photo by Kristin Marzullo New leads heat up cold case Senior Sarah Szoka decorates her advi- sory’s Christmas tree during their Toys for Claybrook missing. mystery of Claybrook’s death “really hits Jenny Hottle, Caroline Spath Tots collection. Advisories are working to On March 10, an off-duty police of- you forever.” Online Chief, Multimedia Editor support families this holiday season. ficer was walking his dog when he found While no signs of a struggle were re- Twenty-seven years after the unsolved Claybrook strangled. She was propped up portedly found at the scene of the body, Grace Kim murder of a JC student, recent news tips against a fence less than a mile from her investigators remain unsure as to whether Managing Editor and an ABC 2 News cold case segment home, in a field now known as the Trails Claybrook was killed onsite or placed there have brought attention to the case. at Gleneagles development, located behind later, according to Brad Helm, the Bel Air Advisories have hung their lights and Jennifer Claybrook, class of ’86, was a Maple View Drive in Bel Air. Police Department detective who is cur- even trimmed their trees. -

Military Nanotechnology and Comic Books

Intertexts 9.1 Pages final 3/15/06 3:22 PM Page 77 Nanowarriors: Military Nanotechnology and Comic Books Colin Milburn U N I V E R S I T Y O F C A L I F O R N I A , D AV I S In February 2002, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology submitted a proposal to the U.S. Army for a new research center devoted to developing military equipment enhanced with nanotechnology. The Army Research Office had issued broad agency solicitations for such a center in October 2001, and they enthusiastically selected MIT’s proposal from among several candidates, awarding them $50 million to kick start what became dubbed the MIT Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies (ISN). MIT’s proposal out- lined areas of nanoscience, polymer chemistry, and molecular engineering that could provide fruitful military applications in the near term, as well as more speculative applications in the future. It also featured the striking image of a mechanically armored woman warrior, standing amidst the mon- uments of some futuristic cityscape, packing two enormous guns and other assault devices (Figure 1). This image proved appealing enough beyond the proposal to grace the ISN’s earliest websites, and it also accompanied several publicity announcements for the institute’s inauguration. Figure 1: ISN Soldier of the Future. 2002. Reproduced with permission. Intertexts, Vol. 9, No. 1 2005 © Texas Tech University Press Intertexts 9.1 Pages final 3/15/06 3:22 PM Page 78 78 I N T E R T E X T S As this image disseminated, it wasn’t long before several comic book fans recognized similarities to the comic book Radix, created by the frater- nal team of Ray and Ben Lai (Figure 2).